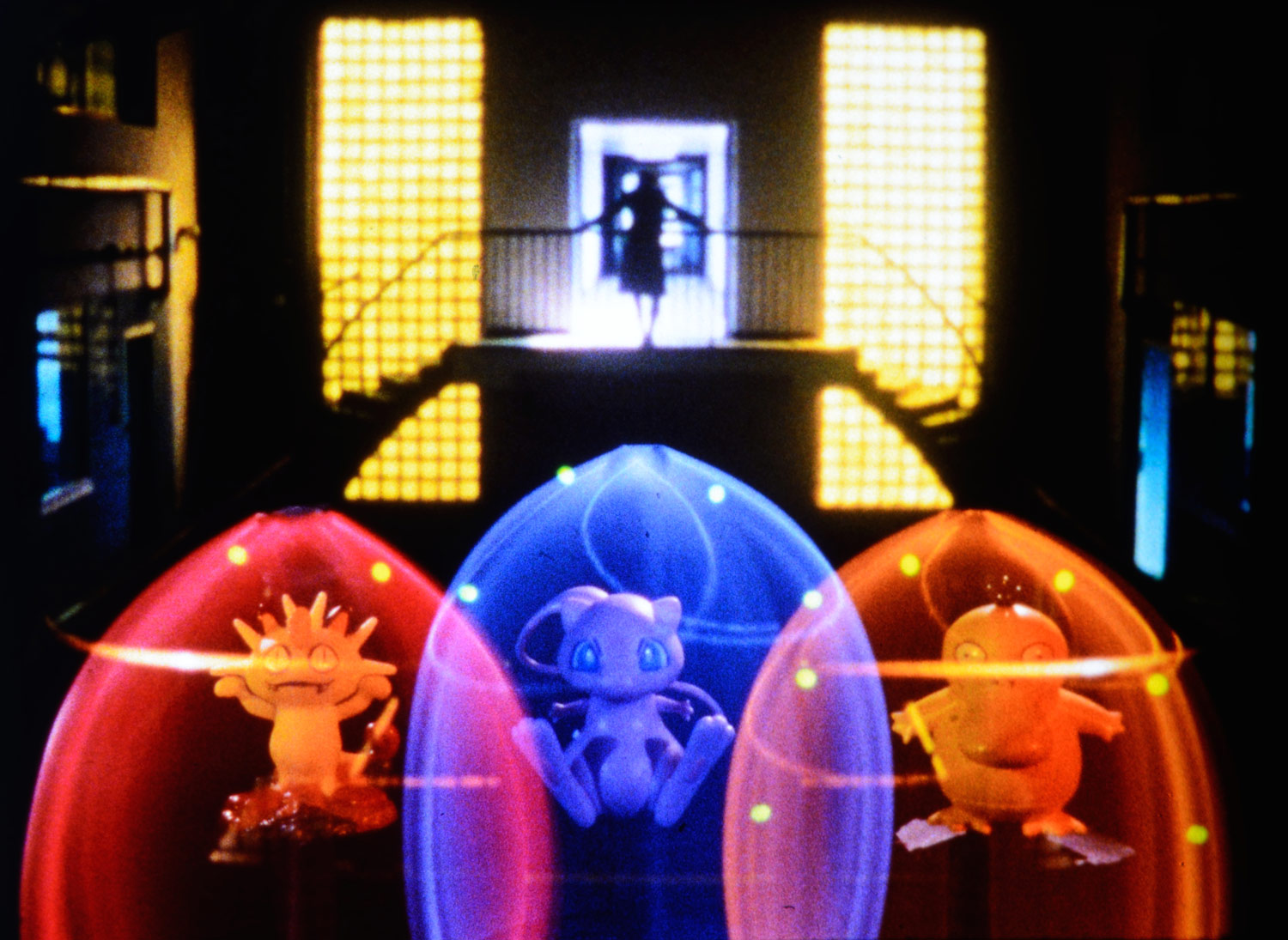

Still from Bi Gan, Resurrection (2025).

Many critics have described the recently concluded edition of the Cannes Film Festival as one of the best in years. Rather than offering an overview of the most interesting films screened on the Croisette over the twelve days of the festival, I will instead attempt to identify a few overarching trends.

American Cinema, Not So Great Again

The first trend—and perhaps the most striking, especially for its extra-cinematic ramifications—is the increasingly evident crisis of American cinema, particularly when measured against expectations. This crisis is all the more significant given the current historical and political conjuncture. It inevitably becomes an allegory for a broader collapse of the American social pact and its cultural discourse. The American films shown at Cannes conveyed the impression of a cinema increasingly turned inward, ever more hypnotized by its own ideological references and the provincialism of its discourse. An emblematic example of this is Eddington, one of the festival’s most anticipated titles.

The film is Ari Aster’s attempt to condense into a two-and-a-half-hour feature, set in a small New Mexico town, all the ideological tropes that have defined the United States in recent years: Covid, conspiracy theories, Black Lives Matter, white privilege, MAGA, memes, Fox News, conservative podcasts à la Joe Rogan, and so on. The film aims to diagnose American ressentiment in the age of Trump 2.0, but it is pervaded by a staggering contradiction: everything is at once immediate, hyperemotional, exaggerated, over-the-top—and yet also over-mediated, self-referential, caught in a maze of inside jokes, meta-commentary, and cultural niches that render it nearly unintelligible to those not fully immersed in American culture.

Eddington is not only a mediocre and politically ambiguous film. It is, above all, a symptom of a particular trajectory that contemporary American cinema seems to be taking, one increasingly shaped by online culture and driven by cultural “bubbles” in which every statement becomes both itself and its opposite, a proliferation of ideological references and objects that often spiral into labyrinthine, centrifugal patterns. In this hyper-contemporary sense, Eddington reminded me of two recent American indie films: www.RachelOrmont.com by Peter Vack and The Code by Eugene Kotlyarenko.

A similar tendency could also be observed in Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest, screened in the Cannes Première section: a Black, New York–based remake of Kurosawa’s High and Low set in the world of pop music, where debates between fathers and sons about social media popularity and the risk of cancellation replace the moral dilemmas—still all too modern—of Kurosawa’s original.

Lee’s and Aster’s cinema are marked by an excess of signifiers: everything is already a sign, everything is pre-interpreted, everything already mediated by an overabundant language. This reflects not only the return of America’s imperial repressed unconscious—where American culture is mistaken for global culture tout court—but also a specific mode of engaging with the image. In both Lee’s and Aster’s films, there is an overflow of images that refer to something outside the cinematic text: images that can only be understood contextually, through allusions to a pervasive social commentary in which the key to understanding always lies elsewhere. The result of this structure of constant deferral is that the image gets subordinated to the demands of a linguistic superstructure. It can no longer be interrogated directly in its mystery and ambiguity.

In contrast to this trend, Cannes also offered its exact opposite, a passion for minimalism exemplified by Christian Petzold’s splendid Miroirs No. 3. Here, the German director reduces the elements of his mise-en-scène even further than in the already minimalist Afire, arriving at a narrative structure composed of only a few key signifiers. The film tells the story of a young woman who, while en route to a vacation with her husband, is involved in a car crash that kills him and leaves her in a state of psychological shock. She is rescued by an elderly woman who, as we soon learn, is herself grieving the suicide of her daughter. From the encounter—indeed, the clash—between their two incompatible experiences of mourning, the narrative unfolds, and the tensions between the two women gradually take shape and find expression.

Petzold’s film is the exact opposite of Aster’s. Like a classic 1940s Hollywood film, all the elements necessary to understand the image are made clear to the viewer in the opening minutes. If Eddington submerges us in the opacity of a jungle of ideological signifiers, Miroirs No. 3 cultivates the illusion that cinema can still be a place where processes of signification and identification can occur transparently. It’s not that Petzold is unaware of the world we live in or of how images are consumed today. Rather, his conviction seems to be that cinema, regardless of when it was declared “dead,” can still be a utopian space in which the ambiguity of the image, reduced to its essential core and stripped of any redundant interpretive layers, can be inhabited in a productive way.

The Hors-champ of War

Although film festivals often feel like bubbles detached from the world, it was nearly impossible for Cannes to ignore what has become, and continues to be, the hors-champ par excellence of recent months: war. Walking around the Croisette, one could see posters in memory of Fatima Hassouna, the Palestinian journalist and photographer, and the protagonist of Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, who was killed in Gaza by an Israeli airstrike on April 16, just one day after it was announced that her film would be screened in the ACID section of the festival.

But most of the time, war enters the world of images obliquely, indirectly—like in Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk. Directed by Iranian filmmaker Sepideh Farsi, now exiled in Paris, the film was initially supposed to document firsthand what was happening in Gaza. It opens with Farsi’s attempt to reach the Strip via the Rafah crossing from Egypt, only for her to quickly realize that such a project would be impossible. Gaza’s images are destined to remain hors-champ, because their erasure—whether through forced invisibility or manipulation—is itself part of the war strategy. The question then becomes: What can be placed in their absence?

Farsi contacts Fatima Hassouna, and the two begin a long FaceTime exchange that spans more than a year of war. What emerges from Hassouna’s testimony? In terms of content, very little: a few anecdotes about daily life under siege and some general political reflections. For the most part, the film is a series of “Can you hear me?” and “Do you see me?” questions, interrupted connections, blackouts, slow internet, and pixelated images. In a word: glitches1—images that are messy, blurred, unreliable. And yet, where content fails, the form of the image itself speaks. It indirectly expresses the gaps and impossibility of representation during wartime.

Farsi’s film recalls the extraordinary work of Lithuanian director Mantas Kvedaravičius on the siege of Mariupol, before his tragic death on the front line in March 2022. (How many filmmakers and photographers have died trying to capture images of war?) In Mariupolis 2, screened at Cannes in 2022, the invasion of Ukraine was also depicted through repetitive, seemingly trivial acts: gathering fuel, cooking soup, fixing a generator, digging through rubble. In the absence of meaningful content, only repetitive, everyday images remain. Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk and Mariupolis 2 are extremely important films, but also almost unbearably boring—expressing something precisely by revolving around a void. Perhaps it is true, as Asia Bazdyrieva argued in her illuminating “An Epistemic Warfare,” that war—referring specifically to the invasion of Ukraine—“is not something that is easily seen.” It is a phenomenon structurally resistant to visual representation, even when it is “saturated with images and other kinds of information,” which resemble more environmental pollution than tools of understanding.2

Another film that tackled the question of representational totality, or its impossibility, was Militantropos by the Tabor Collective (Yelizaveta Smith, Alina Gorlova, and Simon Mozgovyi), screened in the Quinzaine des Cinéastes. Spanning several years and multiple perspectives—all internal to the Ukrainian resistance—the film attempts to capture the complexity and fragmentation of wartime experience, blending embedded footage from the front with scenes of daily life in cities under siege. But the goal is not to seek a “true” image, nor even to document Russian war crimes (already extensively documented), but rather to portray war as a process of subject-formation, or as an anthropological dispositif (as suggested by the title, which combines the Latin “miles/militis,” or “soldier,” and “anthropos,” or “man”), fully embracing its own partiality. There is no shot reverse shot—the directors clarified during a Q&A that they chose to remove all interviews with Russian prisoners—nor any aspiration to objectivity. The image becomes a tool of subjectivation, and in Ukraine, of resistance.

The political film of the festival—and undoubtedly one of the most emblematic of this year’s edition—was It Was Just an Accident by Jafar Panahi, which deservedly received the Palme d’Or. Here too, as in Petzold’s film, the story begins with a car accident. A father at the wheel, a pregnant woman, and a young daughter, who all appear to be from an upper-class background, are driving through the night on a rural road in Iran. Suddenly, a brief encounter with contingency: an animal (a dog?) crosses the road, and the car hits it. A minor incident—indeed, a “simple accident,” as the original title reads, seemingly insignificant enough to pass without consequence. And yet, the man is unlucky: the car won’t restart, and he is forced to bring it to a mechanic by the roadside.

There he meets Vahid, the owner of the garage, who is suddenly gripped by a small acoustic detail that ruptures the tranquil routine of the present: the creaking sound of a prosthetic leg, which reminds him of the torturer who abused him for months in prison during the Syrian war. Is it really him? Or is it merely coincidence? This is a classic Panahi theme: the image can be revealing, but also deceptive. Above all, can we truly trust what we see before our eyes? Is this man truly one of the criminals and torturers of the Iranian regime, or is it a trick of perception, or perhaps even of conscience?

Panahi, after years of imprisonment, house arrest, bans on filmmaking, and the long, well-known saga of his confrontation with the regime, returns with a fully realized film after his clandestine experiments of recent years. And he does so with an extraordinary work that combines the philosophical and formal sophistication that has always characterized Iranian cinema with a powerful political gut punch: an uncompromising accusation against the Tehran regime.

The film revolves around the uncertainty of a man’s identity, but also, and perhaps more importantly, around the fundamental ethical question that confronts every militant when the balance of power is suddenly, unimaginably reversed: What would we do if we came face to face with our torturer? Would we repay him with interest for what he did to us, thus inevitably becoming, in some measure, like him? Or must our relationship to violence already prefigure a path of emancipation from it?

Like all great films, It Was Just an Accident will be remembered above all for a single, unforgettable scene—one that, among the many hours of screenings across two weeks of the festival, stands out indelibly in all its force: the final confrontation between the torturer, tied to a tree on a rural road in the dead of night, and two of his victims. The entire scene is lit only by the blazing red (or blood-red) taillights of a car staring them in the face. It’s a reckoning that serves less to resolve the plot than to dramatize a universal conflict, one that the film’s brilliant conclusion throws back at us in all its dialectical ambiguity.

Kleber’s Memory

The Best Director award was deservedly given to Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho, whom I discussed in 2023 for his magnificent Retratos Fantasmas, to which this latest film, O Agente Secreto, is closely related.3 Mendonça Filho’s cinema has always had a self-referential structure, rich in internal echoes and recurring themes: memory, the entanglement of collective and personal history, and, of course, the role of images and of cinema itself.

On the surface, O Agente Secreto appears to be structured as a spy story—and indeed it seems to follow that genre, at least in its first part, which revolves around the most classic of McGuffins: the discovery of an enigmatic object that sets the plot in motion. In this case, it’s a hairy leg found inside the belly of a shark at Recife’s Oceanographic Institute (we later learn that it’s an urban legend, or at least we never really discover the leg’s true origin). The protagonist, Marcelo, is an engineer returning to Recife in 1977 to reunite with his son during Carnival. In truth, he is surrounded by a community of “refugees”—implicitly, a group of communist militants who, like unions, were banned during Brazil’s two-decade military dictatorship, and who operate clandestinely through a dense, informally organized network of solidarity (beautifully depicted in the film). But Mendonça Filho’s ambitions go far beyond a well-executed period piece. By the end of the first chapter, we are abruptly transported to an archive in present-day São Paulo. Two young students are listening to the tapes that Marcelo and his comrades recorded during that year while being hunted by regime-backed gangsters and the military police. The perspective shifts, from one that is embedded in the unfolding events, to that of those who are attempting to reconstruct the past through the interpretation of its fragments.

Indeed, Mendonça Filho’s cinematic world has always been that of someone standing at the threshold of historical transition, when the past is about to vanish, yet still remains fleetingly intelligible. (Much like the world of cinema itself in the digital age, when we again glimpse Recife’s movie theaters, whose disappearance was mourned in Retratos Fantasmas.)

In fact, the resolution of the spy story involving Marcelo—the conclusion of the film’s plot—is never shown to us in the present, but only as a fragment from the past, retrieved in the future. It is presented through the eyes of a contemporary Brazilian student who did not participate in those events, but who, for some unfathomable reason, feels summoned by them. In the final encounter that closes the film—between the twenty-something archivist in São Paulo and Marcelo’s son (who knows almost nothing about his father’s story)—there is something of an ethical call. As if to say: the problem with the past is not its disappearance (which is inevitable), but knowing how to interrogate it—that is, knowing how to inhabit those traces and that distance. Which, of course, ultimately means learning how to look.

In cinema we normally see the past in the form of a reconstructed present: we cultivate the illusion of inhabiting the past we are watching, as if it were our present. In short, cinema shows us the past as present; we never see the past as past. Mendonça Filho’s idea of cinema, by contrast, is not to translate everything into the present, but to view the past while preserving its distance—its radical inaccessibility. Hence the nostalgic and melancholic aura that pervades many of his films.

But it is only on the surface that O Agente Secreto plays with the structure of a historically reconstructed drama. Or rather, it plays with our habit of immersing ourselves in the present-tense reconstruction of the past—only to take it away at the most crucial moment (precisely when we are about to witness how Marcelo’s story unfolds). By contrast, the fantasy that haunts the present is evoked in the film’s final image, which shows a modern office building standing where a movie theater once did, as if to say: if we want to resist the generalized amnesia that flattens everything into the eternal present of the commodity form, the first antidote is still cinema itself—the practice of those who know how to recognize such traces.

The Resurrection

Some attendees in Cannes complained that a film as dense and theoretical as Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan’s Resurrection (awarded the Special Jury Prize) was screened at the very end of the competition, when the attention spans of audiences and critics had become a scarce resource. And yet, if there is one film whose placement could only be at the end, it is precisely this one. Not only because, in line with many reflections over the past two decades on the end of the cinematic century (Holy Motors above all), Resurrection is itself a film that overtly meditates on the end of cinema. But also because Bi Gan’s own artistic trajectory testifies to a certain passage beyond the cinematic dispositif, moving ever closer to the aesthetic register of contemporary video art—something this film too bears witness to.

The premise of the film recalls that of Bonello’s The Beast (another film about the end of a certain regime of the image and modern subjective experience). We are in a world where the ability to dream has disappeared, and with it, the illusory and phantasmatic dimension of the image. The capacity for dreaming is only preserved by beings known as “Fantasmers” who can “bring chaos into the world” and manipulate time. The narrative revolves around them and other figures capable of engaging with them (the so-called “Big Others”); it unfolds as a journey through the history of cinema, structured across a two-and-a-half-hour cascade of dreamlike images. What lasts a hundred years—the century of the cinematic image—for the Fantasmers will, for the woman played by Shu Qi and for us viewers, coincide with the duration of the film.

But Bi Gan deliberately intersects multiple layers of dissonance. The first is a journey that traverses the twentieth century through a profusion of cinematic references, from the Lumière brothers, Caligari, and German expressionism to The Lady from Shanghai, Blade Runner, Hong Kong gangster cinema, and finally Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times, the true meta-reference of the entire film. The second layer is a meditation on time, the central element that both cinema and the Fantasmers are capable of manipulating—culminating in a kind of final ending, the end of cinema as the end of time conceived under modernity. The third layer consists of a philosophy of perception, which, across the film’s various chapters, moves sequentially through the five senses: from sight, to hearing, to taste, to smell, and finally to touch, which culminates in an epiphanic renunciation of any possibility of controlling the image.

Underlying all of this is a traversal of the cinematic dispositif itself, since the Fantasmers, like dreamers, are both creators of images and their viewers. It is precisely in this overlap between activity and passivity, between spectator and object, between watching and being watched, that the film reaches its zenith. The culmination arrives with the separation of these functions, when the gaze detaches from a vampire (one of the incarnations of the Fantasmers) who finally becomes an object within the image and no longer simply its point of view. It is in this moment of isolating the gaze that we should read not only the final long take (by now a stylistic signature of Bi Gan’s cinematic “endings”) but also the fulfillment of cinema’s historical mission: to emerge from fantasy—literally burning the spectators, as if they were wax—so that the gaze might be liberated from its twentieth-century form.

What comes next? Not death, Bi Gan seems to suggest, distancing himself from the nostalgic, elegiac tones so often invoked in discussions of cinema’s end. What comes next is rather cinema’s resurrection. With this resurrection, cinema will likely assume a different form, toward which Bi Gan—through his increasingly art-like, contemporary aestheticization of the image—is already moving.

According to Laura Marks, glitches reminds us of the “materiality of the support underlying the digital image: a materiality that constitutes an everyday problem in poorly infrastructured countries, including most of the Arabic-speaking world … We experience glitch as a disruption of picture or sound normally delivered by quantified packets of information … Glitch is the surge of the disorderly world into the orderly transmission of electronic signals, resulting from a sudden change in voltage in an electrical circuit. Ideally transmission is perfect, but in fact it almost never is. Glitch reminds us of the analog roots of digital information in the disorderly behavior of electrons.” Laura Marks, Hanan al-Cinema: Affections for the Moving Image (MIT Press, 2015), 251.

Asia Bazdyrieva, “An Epistemic Warfare,” 20 Seconds, no. 7 (2024): 127.

Pietro Bianchi, “Cannes Dispatch, Pt. 2: The Awards and Their Ghosts,” e-flux Notes, May 31, 2023 →.