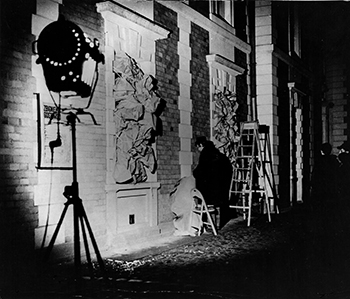

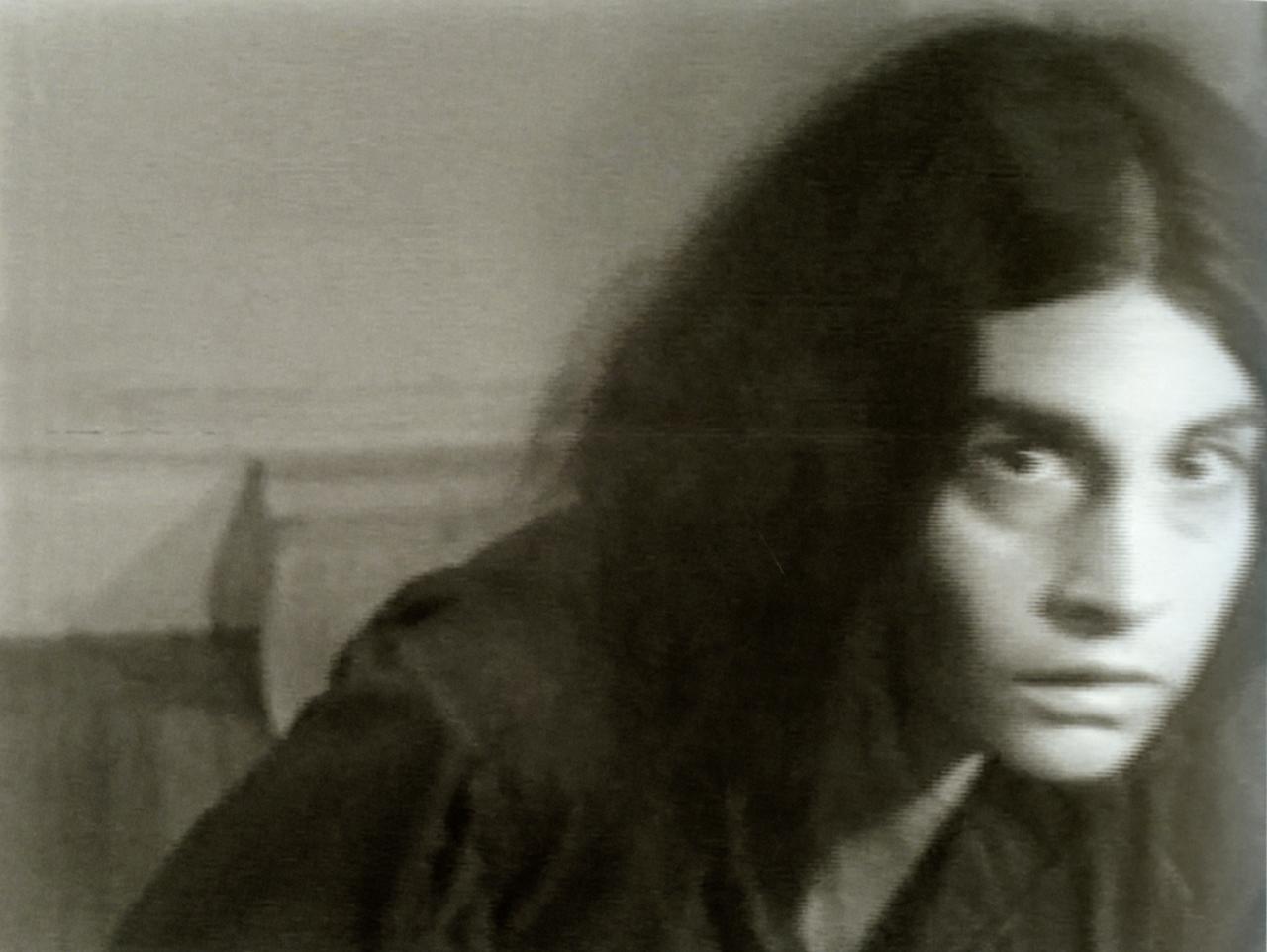

Still from Dara Birnbaum, Addendum: Autism (1975).

I didn’t know Dara Birnbaum well. But I knew some of her work, personally. Nearly every morning when I was a fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, I checked her video, for unwanted glitches and un-synced sound. Dara’s work Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–79) occupied gallery 201, the entrance to the contemporary collections on the second floor of the institution. Suspended between two poles, Lynda Carter appeared first on the flat screen, buttoned-down as a secretary, then uncontained as a superhero, spinning, deflecting, and going elsewhere before Wonder Woman Disco trilled from the speakers. The trawl of lyrics, blocked in yellow typeface, scrolled up a blue screen like a karaoke sing-along. Birnbaum had swiped and revived the sound from the Wonderland Disco Band just at the point of obsolescence. When the museum’s audiovisual team pumped up the sound, the falsetto of Deedee Dennard really dragged out the vowels, a life-within-death rattle which stirred the air of the surrounding galleries, pulling viewers into a loop of unrelenting, over-the-top, exasperated sighs. Like Dan Graham (her collaborator), Birnbaum was one of the art world’s conductors of popular music, a facet of her work still somewhat unexamined. I would write about the work’s campy, coded soundtrack in my scholarly work and her remediation of the film edit within video. Both strategies had sparked a debate about the allegorical maneuvers claimed for contemporary artists of her time. Later, when I met the artist at a dinner hosted by the Bard Center for Curatorial Studies in the Hudson Valley, she gave a toast that seemed to match this strange cadence and extended indeterminacy; her position was at once aloof and personal, sober and jocular, grounded by an excessively dour wit. To this day, I remain uncertain whether she was dryly jesting or sincerely earnest. Either way, at times, she could present as prickly, launching a barb before administering the balm of her grin.

Less than a year later, with Stuart Comer and Michelle Kuo, Erica Papernick-Shimizu and Eana Kim, we properly met to discuss the exhibition of her five-channel installation Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission (1990), which was given pride of place in the exhibition “Signals: How Video Transformed The World” (also at MoMA) and graced the cover of the catalog. When Birnbaum arrived at the museum to negotiate the precise positioning of her work, she conversed with every installer, registrar, and exhibition designer. Observing her slow and deliberate interactions with the team provided another window into a position that unrelentingly and recursively calibrated feedback. Her persistent, methodical approach was neither studied nor spontaneous, neither canned nor unsalted. Rather, it was guided by a decades-long practice of probing and penetrating the tightly controlled messages managed through the cold circuitry of mediation.

For Birnbaum TV news was as troublesome as a repeated hook. The former seemed to offer its spectators an immediate, intimate view, and the latter could veer toward bored and bare repetition. “TV tried to let you think that you could be inside, engulfed by the image and the action and the activity. But what aspect of it?” she’d query.1 Since then, Birnbaum has become renowned for surgically fragmenting the televisual image and undermining the perspectives that our screens train.

She opposed both the intimacy of television and the quality of attentiveness that media engendered, and she did so most notoriously with the aforementioned Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman. This video has been exhibited as one of the foundational works of the Pictures Generation, yet I’m not persuaded that it registered as such at its first screenings. (For one of the initial viewings, Birnbaum transferred the video to 16 mm so it could be included within a film festival at The Kitchen, a detail not discussed as much as its installation on a single monitor streaming to downtowners through the window of New York’s HH Hair Salon de Coiffure—could you even hear it?—or to revelers at the Palladium dance club, where you probably couldn’t hear anything but it.) With her use of disco, she circulated a queer aesthetic, one that would have been fugitive when the work really got going in the late eighties. This facet implies that one of Birnbaum’s subjects was the force carried through intractable expressions. The refining of the Pictures Generation was 1979, the repackaging in 2009, and yet Birnbaum took up the structural logic used by its arbiters and injected the highbrow method with vagrant gulps and gasps. It wasn’t that she merely bootlegged cassettes, mimicked fast cuts and jump cuts, or flaunted female stereotypes, but that she used these strategies to secrete a tide of queerness, a syntax that could not be governed by prudish academese, though the sound might at first have been written off, if not ignored, by its more normative agents as sexist.

Perhaps Dara was motivated by her time studying in San Francisco; it has been written that she worked with Lawrence Halprin Architects and danced at Anna Halprin workshops. But the Bay Area is also where Hibiscus and Sylvester, members of the theater troupe The Cockettes, a predecessor to the group Angels of Lights worked themselves into self-fashioned costumes and fluidly morphed gender. These queer practitioners made an art of glamourous living by realizing glittered fantasies. They also ridiculed stereotypes by reperforming them, parodying them, deforming them on stage and possibly at home. They knew that the lowliest, basest of material could control you. It seems that Birnbaum may have grabbed an aspect of their campy flamboyance and their tendency to reuse, importing such qualities into her work; she best served her audience by undermining the rules of written language with a sound that induces the heat and shimmer of desire and exhausts it, as phrased by the incandescent and theatrical moans.

To that end, though Birnbaum’s work might have been initially framed as Brechtian, she was no student of Brecht. She never truly distantiated her viewership with the celebrated Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, or with her other works. Rather, she drew us into an alternative listening and viewing engagement. The artist’s interests in kitsch and the tropes of popular culture carries over to Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry, which advances with handclaps that thump off beat, just as the lens zooms in and out on the mugs of minor celebrities (like Melissa Gilbert of Little House on the Prairie), framed by the Hollywood Squares. “Iconic women and receding men,” Dara described them, captured posing in “repetitive baroque neck-snapping triple takes, guffaws, and paranoid eye darts.”2 Both this and the former work clue us into the possibility that Birnbaum used tropes as a way to pull in her viewership and then pull apart the unity of perspective, by surging it with sonic surplus. The audio certainty captivates the ear, and it generates an excess, one which peels away its source material from either side. The initial soundtrack soon mixes into a slowed and synthed rendition of “Georgie Porgie Pudding and Pie.” Music, Birnbaum suggests, provided a model that sampled and remixed with irony, buoyancy, and drag to induce a threshold experience. She transmitted edgewise, overtly signaling a cut and wink within earshot and sight.

The installations of Birnbaum that I find most difficult are the later, clunky architectural interventions of the nineties, like Transmission Tower: Sentinel (1992) and Hostage (1994). It seems that here Birnbaum turned to the minimal grid and then transmitted data through its cubes. She cycled her images over a series of screens, one after another. Even though the monitors can present the picture off beat, cascading the image in shifting patterns that emulate the cadence of the early work, I always felt that she had hedged, that she relied too much on a phenomenological encounter with angular forms. Had she abandoned or had she perverted her dictate from the seventies: “new structures; new approaches”? Or, perhaps more generously, was she again taking up the just-past, this time the geometry of minimalism, and locking its logic into the look of control rooms and spacecrafts?

Birnbaum’s interventions are most productive when she injects fitful resistance into dialectics and surges the connections between satellite, broadcast, and nation. Perhaps it is this potential for her work to pirate that still fascinates me. Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission is guided by powder-coated tubes that telescope from the ceiling. “Each line like a parallel satellite transmission,” Dara explained to us, to teeter, plumbly, LED screens at their ends. The palm-sized displays invite us to crouch, squint, and connect. An adjacent wall monitor zaps between tape of US news, student protests in Beijing, and the notice cutting satellite transmission issued by the Chinese government. The notion here was that the television surveilled what was just seen simultaneously nearby on the screens, only for the broadcast to be dramatically, aggressively interrupted. Dara commandeered the point of view of television—the direct address, the political messaging, the break in news, and the temporal regress—and primed us for our current asynchronous communication. Still, she had no patience for binaries, and she forensically included footage of the youthful power that fomented, that lasted. She also highlighted reels of the students pushing out their illicit messages with teletex and fax machines, circulating a syncopated solidarity through a Taiwanese music video. She knew that sorrows are sung and danced to, to transform memory with bodily beat. The earworm inscribes itself as it moves us along. As Birnbaum guided us to install this monument to persistence, she too endured, somewhat impoverished and in ill-health, even as writers vaunted her as a pioneer—an action which nominates an artist’s initial output at the sacrifice of their ongoing travails. The tendency fails her consistency and creates gaps, leaving her unsung output to the scholars who slowly and belatedly complicate our stories and fill in collections. It makes me wonder about the way artists are able to sustain themselves, to hold conviction, as they are ossified into the symbols that bolster genre, silo discipline. But then, I also recall how Dara truly schooled us: “The in-between,” she admonished, “is really the reality we need to live in.”3

Dara Birnbaum, interview by Susan Canning, Art Papers, November–December 1991, 57.

Dara Birnbaum, Kiss The Girls: Make Them Cry, eai.org →.

Dara Birnbaum in Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews: Vol. 1 (Charta, 2003), 88.