Photograph Aaron Schuster

The following text is based on the book launch for Aaron Schuster’s How to Research Like a Dog: Kafka’s New Science (MIT, 2024), at e-flux, on April 15, 2025.

Investigating Investigations of a Dog

What is this book about? First of all, it’s a detailed and digressive reading of a single short story by Franz Kafka, “Investigations of a Dog.” It’s an attempt to reread or re-encounter Kafka through the lens of this one story. Second, it’s also an attempt to ask a very basic question about the nature of philosophy. What is this strange field or discipline or practice called philosophy? Here I go back to another dog story, one of the masterpieces of the genre of talking dog literature—which is a much richer genre than one might imagine—Miguel de Cervantes’s The Dialogue of the Dogs. Cervantes’s story has a wonderfully complex construction, but essentially it is a conversation between two dogs, Scipio and Berganza. At one point, Berganza says, “First of all, I’d like to ask you to tell me if you happen to know what philosophy means. For although I use the word, I don’t know what it is. All I can gather is that it’s a good thing.” Is philosophy a good thing? Of course, it depends on what you mean by good, but Kafka’s dog is much less optimistic in this regard and suggests that the truth that philosophy seeks, or the precious bone marrow it’s after, is actually a poison.

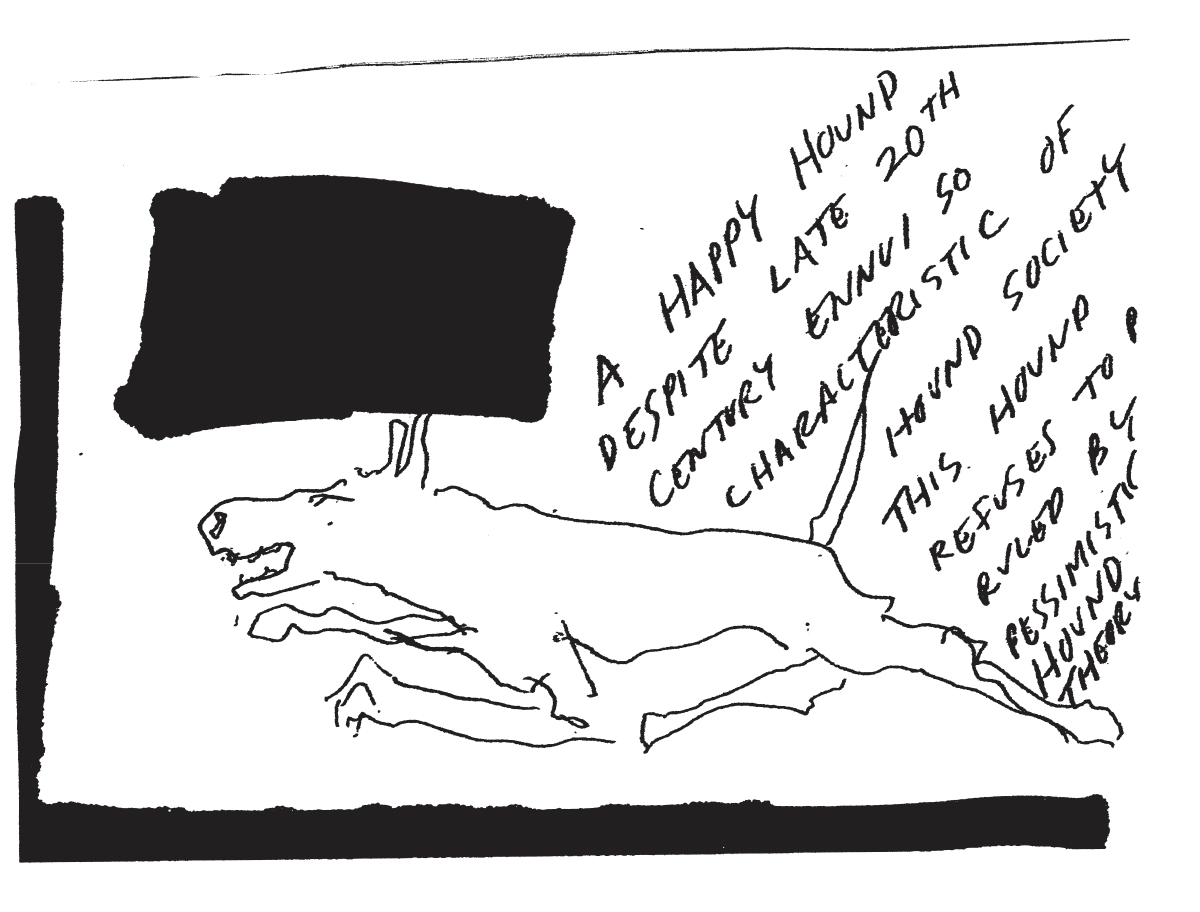

Third, the book is also, if I can put it this way, an artistic wager. I constructed it using a number of formal rules, the main one being that all substantive discussions had to be linked through the figure of the dog. In this way, I wanted to take seriously the claim of Kafka’s dog that “all knowledge, the totality of all questions and all answers, is contained in the dog.” Now, there is no conceptual reason for doing this. There is only a formal and aesthetic one. But it does follow from one of the core arguments of the book, namely that thinking is never strictly conceptual. Thinking is never entirely absorbed in the realm of meaning, but is shaped by meaningless or trivial elements that give it a certain charge or valence. So in this sense, I consider this book to be a kind of experimental writing that I’ve named “potential philosophy” after Oulipo, the workshop for potential literature. The dog served as a rule or constraint that forced the research along certain pathways.

“Investigations of a Dog” is a rather unique story in Kafka’s body of work, where he plays with his own formulas and clichés. It’s about a philosopher dog who goes on all kinds of adventures in theory, trying to understand his world and himself. In particular, he wants to understand his own relentless drive to philosophize, his philosophical disposition or theory drive. I will mention a few ways that the story is unique. It was written in the fall of 1922, right after Kafka abandoned his novel, The Castle, which is essentially the story of a man who cannot get his work permit. Unlike K., the dog is not seeking for permission or authorization from an obscure power, and he doesn’t care about his credentials. He is a self-authorizing philosopher. Also, unlike Red Peter, the ape who miraculously transforms into a man in the story “A Report to an Academy,” the dog is not an object but a subject of research. He sets his own research agenda and pursues his own investigations. Red Peter addresses a distinguished audience of scholars and academics as a curiosity to be studied, a witness providing evidence; the dog, in contrast, is skeptical of established science and addresses his questions to the wider canine community.

Furthermore, “Investigations of a Dog” is the only story of Kafka’s to offer something like a psychobiography of its protagonist. We never get backstories for Kafka’s characters, but the dog ponders the question of his origins, of how he became a philosopher, and he traces his passion back to his youth when he stumbled on a psychedelic concert of musical dogs. This concert functions as a kind of primal scene: the crazy song-and-dance show is what put the nascent philosopher on his path, launching his questions and investigations. Interestingly enough—and I think this is a profound comment, with implications for both our reading of Kafka and our understanding of psychic causality—the dog specifies that the concert didn’t cause him to become a philosopher, but served as an occasion to awaken his underlying philosophical disposition. “I don’t blame the concert,” he says. If he hadn’t come across the concert, certainly something else in his milieu would have triggered his investigative instincts. Imagine Joseph K. saying something similar—I don’t blame those agents of the court, if they hadn’t come to arrest me that morning, certainly something else would have happened to set my guilt complex into motion. When we read Kafka, we find a threefold setup at work: the forces and structures of the social-historical context; the subjective disposition which bends the environment according to its perspective, finding what it needs to feed its voracious drive; and contingent events or encounters—the domain of luck, which, in Kafka, is always bad luck.

Another element that marks this story out is the theme of community. What’s typical of Kafka’s intellectuals and artists is their lust for fame. Kafka is usually read as a critic of power, but he was also an astute critic of the desire for recognition. His artists want admiration, they are desperate for followers. The dog too dreams of fame. He wants to be a theory star, or a thought leader, as we say today. But eventually, this youthful desire gives way to another one, which is more interesting: the desire for colleagues or comrades. Who are my fellow researchers, the dog asks. “Where are my real colleagues? Yes, that is the burden of my complaint. That is the kernel of it. Where are they?” And he concludes, “Everywhere and nowhere.” What I tried to do is to enter into the story, and make myself one of the missing comrades of Kafka’s dog.

The Zero Perspective

To help explain my methodology, I’d like to refer to a joke that Michael Löwy makes in the preface to his own book about Kafka, Franz Kafka: Subversive Dreamer. Löwy repeats a lament that is typical of Kafka critics—there is so much written on Kafka, such a flood of criticism and commentary, what could one possibly add? Why another book? Such is the neurosis of scholars. Ironically, Kafka seems to have anticipated this in his story. When the dog talks about the science of food, he complains that there are so much written on the subject, so many books and essays, not even all dog scholars working together could ever hope to master the field.

Löwy writes: “The multifarious secondary literature has been expanded in recent years by the growing body of tertiary studies, the analysis of the different interpretations of the Prague author. Perhaps there will someday be yet another level, a quaternary literature.” This is just a joke for Löwy, but actually, it’s a good term for designating what I am up to: a quaternary literature. My book is neither simply a secondary study of Kafka, nor is it a tertiary meta-commentary on the commentaries, but it takes a fourth position. What is this fourth position? I am reminded here of a phrase that Gilles Deleuze borrowed from Lawrence Ferlinghetti to describe a kind of writing that would be at the level of the event or adequate to the event, a language of the event itself. He calls it the “fourth-person singular.” In my book, I take on the point of view of Kafka’s dog, of his philosophical event of thinking. I make myself a comrade of the dog by adopting his research program and developing it further. That’s the gambit. Of course, I am concerned with giving, let’s say, a good interpretation of the story, but this is a side effect of the main aim: to treat the story as the sketch of an authentic philosophical system that’s begging for elaboration and in need of new collaborators and comrades to continue the work.

For my purposes, even better than Deleuze’s fourth-person singular is a term invented by a contemporary Dutch philosopher, Wouter Kusters, who speaks of the “zero-th” or “zero-person” perspective, the point of view of paradox itself. Allow me to expand on this bit. In the case of Kafka, to the standard distinction that’s used by critics and professors between primary texts and secondary texts, we should add the notion of the “zero-text.” Kafka’s primary texts are so many attempts to write this zero-text, while at same time guarding against it. They conjure a zero—a void, an absence, a silence—that they equally banish, or wall off, or, indeed, silence. It’s this zero-text that is typically forgotten or misunderstood by the secondary literature in its attempts to explain the primary text. I think the most concentrated expression of this is found in one of Kafka’s variations on Don Quixote, which is maybe my favorite passage in all his work:

One of the most important quixotic acts, more obtrusive than fighting the windmill is suicide. The dead Don Quixote wants to kill the dead Don Quixote. In order to kill, however, he needs a place that is alive. And this he searches for with his sword, both ceaselessly and in vain. Engaged in this occupation, the two dead men, inextricably interlocked and positively bouncing with life, go somersaulting away down the ages.

Tilting at windmills is, of course, the famous Cervantine image for delirium, for fighting imaginary enemies. But Kafka’s Don Quixote doesn’t tilt at windmills; he tilts at himself. He is his own delirious adversary. This provides a precious clue as to the nature of Kafka’s characters, who often appear to be dominated, oppressed, and tortured by external forces, but, in fact, secretly engineer their own obstacles and impasses. They are not only the victims of calamity and misfortune. For they need these obstacles in order to come alive—but precisely as a life that’s “impossible” to live.

Second, one could say that Kafka has invented here a most original philosophy of life: life is a continually failed suicide. One lives by failing to not-live. (Or as Kafka says in his notebooks, “one cannot not-live”). This is a vision of life as a repeatedly failed self-negation, a vision whose dark humor—a kind of metaphysical slapstick—I tried to render with the formula “screwball tragedy.” The quixotic suicide could also be seen as Kafka’s name for what Freud called the death drive, the self-destructive or self-sabotaging propensity of the mind. But in Kafka, the trick is that self-sabotage never succeeds in doing itself in. Self-sabotage is also sabotaged; it inevitably goes awry. And in this failure to negate oneself there is generated a weird vivaciousness as its wayward byproduct—such is the meaning of life in Kafka.

Third, we come to the ontological paradox. What I am calling the zero-text is not beneath or below the text, at a deeper or more fundamental level. Rather it is something that is instigated by the primary text itself, while at the same time robbing it of its primacy or its “ground.” The dead Don Quixote can only kill himself if he can find the last little missing piece of life to extinguish—and his failure to find this missing life is his life. You can’t really understand this, it doesn’t make any sense. There is a kind of magical or paradoxical bootstrapping effect here, like Baron Munchausen pulling himself up by his own hair. In Kafka’s case, it’s the dead suiciding itself into life. What’s dead becomes animated through its failure to find the life it wants to terminate. This life then stubbornly persists by outrunning its own deadness, leaping over the void it’s perpetually falling into, “somersaulting away down the ages.”

Kafka’s failed suicidal Don Quixote is a stunning, and hilarious, figure of a void that’s internal to the text—a void that gives to Kafka’s writing its oddball élan, its peculiarly thwarted dynamism. Kafka will never stop writing this paradox, a paradox that’s impossible to write and that makes writing an “impossible profession.” You can think about this another way: instead of silence preceding the speech that breaks it, silence is positively brought into the world through speaking, as a hole or absence that language can never abolish or “make speak,” but which forever twists and haunts that which is spoken. And one of the lessons of Kafka’s dog is that it’s from this void that one philosophizes. The dog turns silence into an object of investigation—the same silence that he is the living embodiment of.

Two drunken kids watch agog as a drunken dog walks about on its hind legs, in Marshall Neilan’s Daddy-Long-Legs (1919)—one of Kafka’s favorite films, and a possible inspiration for “Investigations of a Dog.”

The Canine System

Let’s turn now to the question of the dog as a researcher and the philosophical system he produces. This system has four parts. First there is the science of food or nourishment, the most developed of the canine sciences, and then there is a higher science, the science of music. And situated between them is what the dog calls the theory of incantation, which is the songs that are sung to procure food—in the dogs’ case, barking and leaping (it’s quite funny). And lastly, there is the ultimate science, the science of freedom. Now, I believe that this is a very compelling system. There has been a lot of interest in philosophy in the last years in creating a new system, but here, already, we find laid out a very creative and innovative one. I will restate it as follows: There’s a science that deals with nourishment, which can be understood as studying what really supports and drives life, the substance of life, or the kernel of our being. Then there is the science of music, which stands for art in general (music is the highest art in Kafka). Between these is the theory of incantation, which is a theory of institutions: institutions are essentially socially organized forms of “incantation,” bridging the span between the realms of vitality and art. They are the rules and prescribed forms for singing the songs we need to sing in order to get what we want—with the proviso that institutions are also self-relating structures, so that what incantations concern, above all, is our place within them. The whole problem of authority and recognition enters here. And lastly, there is the most important question, that of freedom. So, to recapitulate, we have four components: life, art, institutions, and freedom.

On the one hand, I think Kafka is giving us here, in the guise of the dog’s system of science, a roadmap of his own obsessions, a guide to his major literary themes and works. On the other, this system can be read as a kind of parody—a loving parody, I would say—of German Idealism. Kafka’s dog is the woolly companion to Hegel, Fichte, Hölderlin, Schelling, and, maybe especially, Schlegel. I show how Kafka actually fulfilled, in the twentieth century, the project of German Idealism to create a new mythology, a mythology of reason—although the way Kafka does so subverts the original intention of this project; his is more a mythology of neurotic reason, for the Freudian age.

One of the things I tried to do in the book was provide an account for how philosophy sees itself or justifies itself in modern times, in relation to other fields and disciplines. How does philosophy conceive its place in the university? To briefly summarize, I think there are four main answers. The first is as the leader, philosophy as the queen of the sciences. The last great heroic attempt to elevate philosophy to the rank of leading discipline, able to ground all rationalistic inquiry, was that of Edmund Husserl—Husserl’s new science of consciousness, phenomenology. But this idea persists in philosophers’ belief that theirs is the domain of pure ideation, where concepts are created, which then find their way into other fields. Second is philosophy as the servant of the sciences, which derives from the medieval idea of philosophy as the handmaiden to theology. In this conception, philosophy helps the sciences by clearing away epistemological confusions; it makes the work of the sciences easier. Third is philosophy as a specialized discipline, with its own domain of problems and methods, often involving the use of language. In this case philosophy neither leads nor serves but emulates the sciences; this is the idea that animates much of Anglo-American analytic philosophy. Lastly, philosophy can conceive of itself as a consultant, possessing knowledge or wisdom that can be used to solve problems of a societal nature—for example, applied ethics.

This is the language one must use in order to function institutionally, the language of incantation; if you want to justify your project, you need to refer to one or more of these positions. However, cutting across these has always been another, stranger position, which has historically gone by different names: the gadfly, the fool, the ironist, and, indeed, the cynic. When Socrates confronted his fellow citizens in public, they would complain of how he stuns or shames them, that Socrates cannot be pinned down or placed. He’s unplaceable, atopos. Philosophy is the agent of atopia. And here is my polemical point with regard to Kafka’s reception. Practically no one would say that Kafka is a utopian author, although there are some utopian moments in the dog story, like when the dog imagines floating with the pack to the lofty realm of freedom. (Fredric Jameson saw the destiny of art in “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” as utopian, but that’s another story.) Utopia means no place, but it has also taken on the meaning of good place. But I don’t think Kafka should be read as a dystopian author either, the chronicler of the nightmare world of bureaucracy, capitalism, and the state—although he is also surely that. Kafka is neither a utopian nor a dystopian author, but an atopian one. Like the dog says, I’m a bad scholar, I have no head for science, but I do have a nose for the gaps. I can sniff out the nonplace and make it into an object of investigation. And what we need are new ways to approach and reinvent this atopia. Not the leader, the servant, the specialist, or the consultant, Kafka’s new science is a science of a nonplace that itself doesn’t have a place—what we might call, to use another of Kafka’s words, the demon of the sciences.

Psychoanalysis and Kafka’s New Science

One of the most important of these approaches was psychoanalysis. The unconscious is the Freudian atopia. Now, there are many connections between psychoanalysis and what the dog calls his new science. But the link between Freud and Kafka really runs through one author: namely, Cervantes. Both Kafka and Freud were fascinated with Cervantes, and specifically Cervantes’s dogs. When Freud was a teenager, he resolved to teach himself Spanish by entering into a correspondence with his friend Eduard Silberstein; and they used The Dialogue of the Dogs as the basis for their exchange. Writing to each other in broken Spanish, Silberstein signed his letters “Berganza,” the name of the loquacious, storytelling dog, and Freud “Scipio,” the name of the more silent dog, who punctuates Berganza’s speech with comments and observations. So we have a kind of funny anticipation of the psychoanalytic setup. Freud also gave a special name to their association: the Spanish Academy, the Academia Española—you see already at a young age Freud’s institution-building ambitions. Before the International Psychoanalytic Association, there was the Academia Española. And this institution had all sorts of rules and secret codes, and also its scandals. It ends quite tragically: sometime after the correspondence had finished, Silberstein sent his wife, who was apparently suffering from melancholia, to be treated by a young Dr. Freud in the early days of his practice. As the story goes, she went to the building where his office was, but instead of seeing him she climbed to the third floor and threw herself out a window and died. Not so long after, Freud moved to his office at Berggasse 19, where he stayed for almost the rest of his life. So, at the origin of psychoanalysis, there is a dialogue of the dogs. Kafka too was a great reader of Cervantes, and kept rewriting him in different ways, giving his version of The Dialogue of the Dogs in “Investigations of a Dog.” We might see in this fortuitous crossing of literature, psychoanalysis, and philosophy something like a secret canine history of modernity.

My aim is not to psychoanalyze Kafka; if anything I think that it’s Kafka who can help us to specify what is at stake in psychoanalysis, and what makes it worth thinking about today. Coming back to the theme of atopia, I want to highlight a passage from Kafka’s diaries that I think brilliantly spells out what the research domain of psychoanalysis is, and what the subject could be for a new science. Kafka writes: “I have crossed this borderland between loneliness and community only extremely rarely. I’ve even settled there more than in loneliness itself. What a lively and beautiful land Robinson’s Island was in comparison to it.” Now, Kafka is often associated with the theme of loneliness. There’s a book by one of my favorite Kafka critics, Marthe Robert, titled As Lonely as Kafka (Seul comme Franz Kafka). But I think this is the more precise formulation of what is at stake in his fiction: neither the isolated individual nor the community, neither solitude nor being-together, but a kind of nonplace, a borderland between loneliness and community.

What is this borderland? When the social world, or the symbolic order of the community, can’t answer a person’s questions or provide a resolution to their crises—when a person is on the point of falling out of the world—they are forced to invent their own ad hoc solutions. This is not simply a matter of creativity but of necessity. One is compelled to invent or improvise, whether one wants to or not, unconsciously, at the margins of culture, history, language, and shared experience. These improvised solutions, or what psychoanalysis calls symptoms, give the subject a bearing, a kind of anchoring in being, when they are threatened with the loss of all such bearings. In their stubborn idiosyncrasy, they both separate the individual from the community and reconnect the person back to the world. They give them the means for expressing and dealing with their problems rather than simply drowning in them. Kafka’s formulation provides, I think, an essential clarification of the psychoanalytic conception of the symptom as a compromise formation. Usually this is taken to mean that a symptom is a compromise between the drives and the limitations imposed by reality, or else a compromise between competing drives. It’s a mangled attempt to solve a conflict that’s essentially unsolvable, to have it both ways. But in Kafka, the symptom should also be seen as a compromise between worldlessness and being-in-the-world, between sheer mute isolation and partaking in communal life. Neither being nor nonbeing but the border between them. That’s what Kafka adds to the Freudian definition of the symptom as a compromise formation.

Human beings are creatures of the border. There is a part of life that can never be shared in common and that can only be lived in the borderland between loneliness and community. If there’s something like an ethical lesson in the book, this is it. And therein lies the twist that Kafka gives to the problem of community. In searching for a new community, in calling his fellow dogs to join him on his quest, Kafka’s dog discovers the borderland at the limits of community: how all dogs share in the condition of being maladjusted in their own manner, how all are united in being fated to pursue their singular “investigations.” One might call it a Kafkian solidarity.

In the twentieth century psychoanalysis was a new science that opened up this domain in an original way. Psychoanalysis investigates the production of symptoms at the most problematic and vulnerable points of human existence, where neither nature nor culture provides a reliable guide. These include sexuality and sexed identity, the problem of embodiment, mourning and melancholy in the reaction to loss, and the ambivalent relation to authority—these are some of the main problem areas that psychoanalysis investigates. But psychoanalysis is not the only approach to this border domain. For Kafka, it was literature. And we also might also conceive art in this way, despite the usual identification of art with culture as such. Art is situated within and investigates the borderland containing that which falls out of culture yet without disappearing from it. For Kafka’s dog, this is to be the object of a science of the future, which would also be a science of freedom.

From Leon Golub, Dog (2004)

Kafka’s Misdiagnosis

Incidentally, I think that Kafka has been largely misdiagnosed by the psychoanalytic literature. For the most part, but not exclusively, Kafka is talked about as a schizophrenic writer. This reaches its apex in Deleuze and Guattari’s book on Kafka. There are some good reasons for viewing Kafka this way, in particular the bodily transformations or metamorphoses in his stories, and the world cataclysms, the sense of ontological precarity. But fundamentally this interpretation is wrong: Kafka belongs to a neurotic universe, and the more schizophrenic elements you find in his work are framed by this neurosis, they are part of it. In Kafka, what matters is the ambivalent relation to authority, the quest for authorization and permission, doubt (as opposed to psychotic certainty), hesitation, raised to the level of method, and, above all, failure—the failure to attain one’s goal, or simply to move from point A to point B. This would need to be developed further, of course. I’ll just mention here that one of the authors who put me on this track was Samuel Beckett, who claimed that unlike his characters, who are disintegrating into dust, Kafka’s protagonists are lost yet nonetheless possess a certain “coherence of purpose.”

One of the things that literature can do is to stylize or aestheticize psychopathology—not in the pejorative sense, and certainly not by “romanticizing” mental illness, but in the sense of exploring its dynamics and complexities, of showing it to be not merely sickness and dysfunction but a way of grappling with very human problems, and to constitute even a style of being. Lacan once called Hegel the most sublime hysteric, a line which has been widely cited by Slavoj Žižek. I think Kafka is the most sublime obsessional neurotic. He investigated this particular form of anchoring, and raised it to the level of a style of being—a most hesitant style. Like Kafka said, “There is a goal, but no way. The way is hesitation.”

This is perhaps most manifest in his complaining. I would even say that Kafka is the greatest complainer in twentieth-century literature. He’s a truly gifted, virtuosic complainer, and also a supreme anatomist of the complaint—many of the stories read like long complaints. Kafka cultivates his complaints, which for him are more than just a coping mechanism, or an appeal to an external authority for redress. He turns complaining into a kind of poetics. This can be quite humorous, and touching. At one point he writes to Felice Bauer, “If we cannot use arms, dearest, let us embrace with complaints.”

Like a Dog

Now, the dog in “Investigations of a Dog” is clearly not your usual dog. But neither is he simply a fable-like stand-in for a human being. Rather, Kafka’s animals, crossbreeds, and uncanny nonhumans emerge at a precise point. They are the spokescreatures of a precarious borderland where the human-ness of the human being comes undone. They speak from and embody a crisis in the human self-image, when one can no longer identify with that ideal image or “misrecognize” oneself in it.

The notion of human superiority or exceptionality is never only about animals but is also, above all, directed against other humans. Historically this involves the segregation of humanity into real humans, or real “men,” and subhuman “dogs.” The word “dog” has often served as a slur against supposedly inferior groups; there are, unfortunately, countless examples of this. In Kafka’s milieu, it was an anti-Semitic slur. During the Vichy regime in Martinique, Aimé Césaire wrote a play about the Haitian Revolution titled …… And the Dogs Were Silent. Kafka satirizes this colonial mentality. One of the things that’s funny about the dog story is that it’s the dogs who act arrogantly toward other animals, whom they regard as inferior, sub-canine creatures to be scientifically studied, and who are in need of their “humanitarian” (or rather cynotarian) intervention and care.

But “Investigations of Dog” doesn’t end with a dog. Beyond the animal narrator there is a plant. So there are not only Kafka animals but Kafka vegetables. The story concludes with the dog making a claim for freedom, which he describes as a puny plant or a wretched weed. Instead of freedom being connected with human flourishing and self-realization, like a flower blossoming in the sun, it is associated with something misshapen, with what doesn’t grow right. This cuts against a whole metaphorology. The Ancient Greek word for freedom, eleutheria, contains a plant metaphor. As the linguist Emil Benveniste explains, it’s the freedom of the “growth group,” the right ethnic stock that develops its capacities in the right way. One could say that, for classical humanism, freedom is a vegetable freedom: it refers to the right plants that grow in the correct way. Taking inspiration from Kafka, I think the challenge lies in rethinking freedom not in terms of self-realization and social flourishing, but starting from the maladjustment, the break point, the folly, the gap. And so, as the dog says, we need a new science of freedom.

Why a dog? “Investigations of a Dog” is a particularly significant story because of the meaning that the word “dog” held for Kafka. It was interesting for me to discover that almost every reference to dogs in Kafka is negative. It’s always dying like a dog, or working like a dog, or chasing one’s tail like a dog, or copulating on the floor like dogs, or being sliced up like a sausage and fed to a hungry dog, and so forth. The only other author who had such a negative view of dogs is Shakespeare. The dog is Kafka’s metaphor of abjection, his master curse word. You know the famous line from The Trial: when Joseph K. is assassinated he says “Like a dog!” In fact, this ending was anticipated in an early letter to Max Brod where Kafka wrote, “My future is not rosy and I will surely—this much I can foresee—die like a dog.” It seems that this image stuck with him for many years, eventually becoming that climactic scene in The Trial.

One of the things that I find so fascinating about “Investigations of a Dog” is that in it the whole thing gets turned around. The dog is no longer just the insult, the infamy, the abjection, the miserable death. No: this dog himself gains a voice. The curse itself speaks. And the question is, what does the talking dog say? If a dog could speak, what would he say? Kafka’s answer is both surprising and perfectly logical: he would complain about language. To speak is to have a sense for the failure of speaking, a sense for the unspeakable. And “dog” is the closest thing in Kafka for a name for the unspeakable. And so the talking dog laments that the true word is missing, and his “hopeless yet indispensable” investigations turn around this gap in language, which he is particularly talented at sniffing out. To research like a dog means to investigate the missing word that one is.