Martha Rosler Library

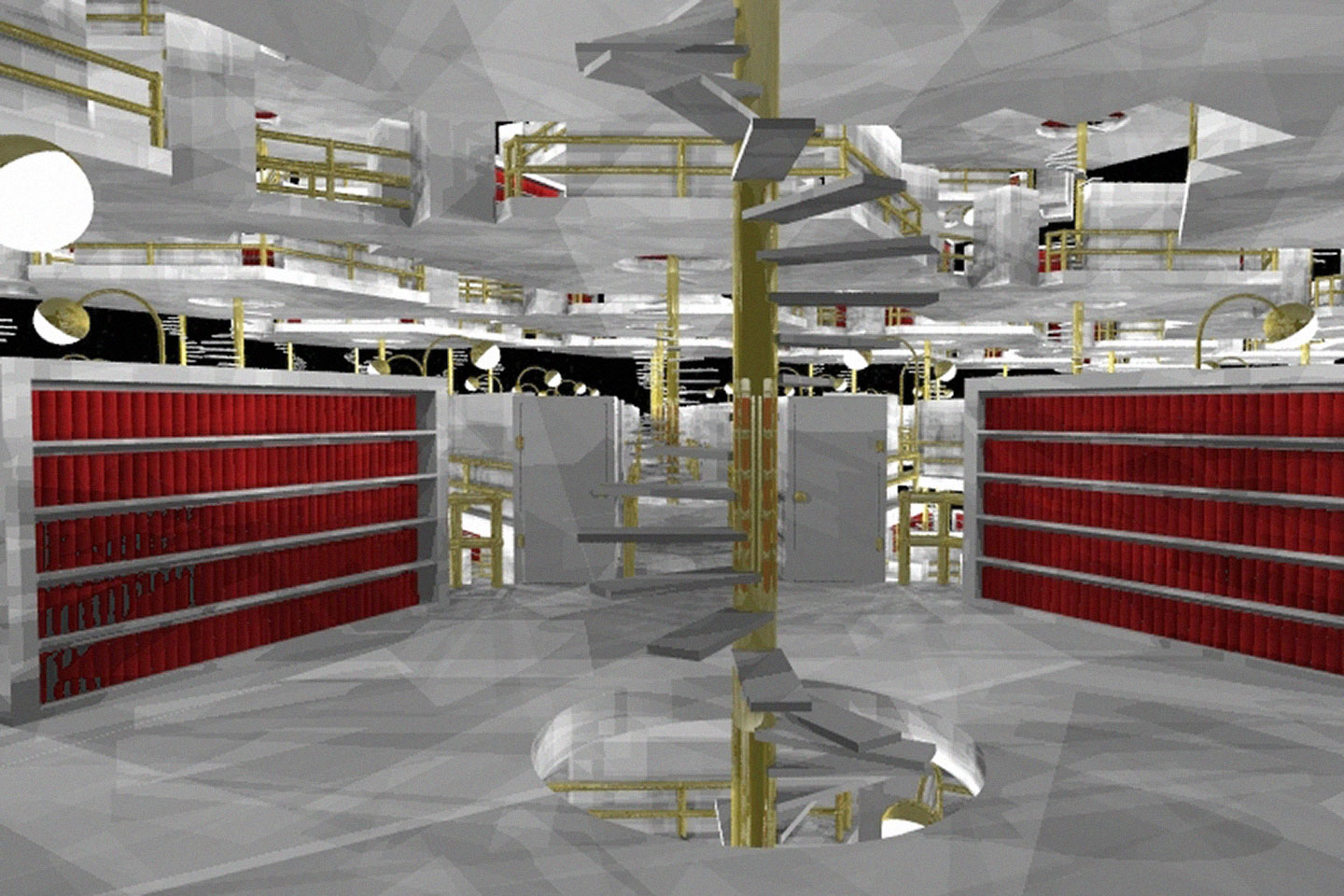

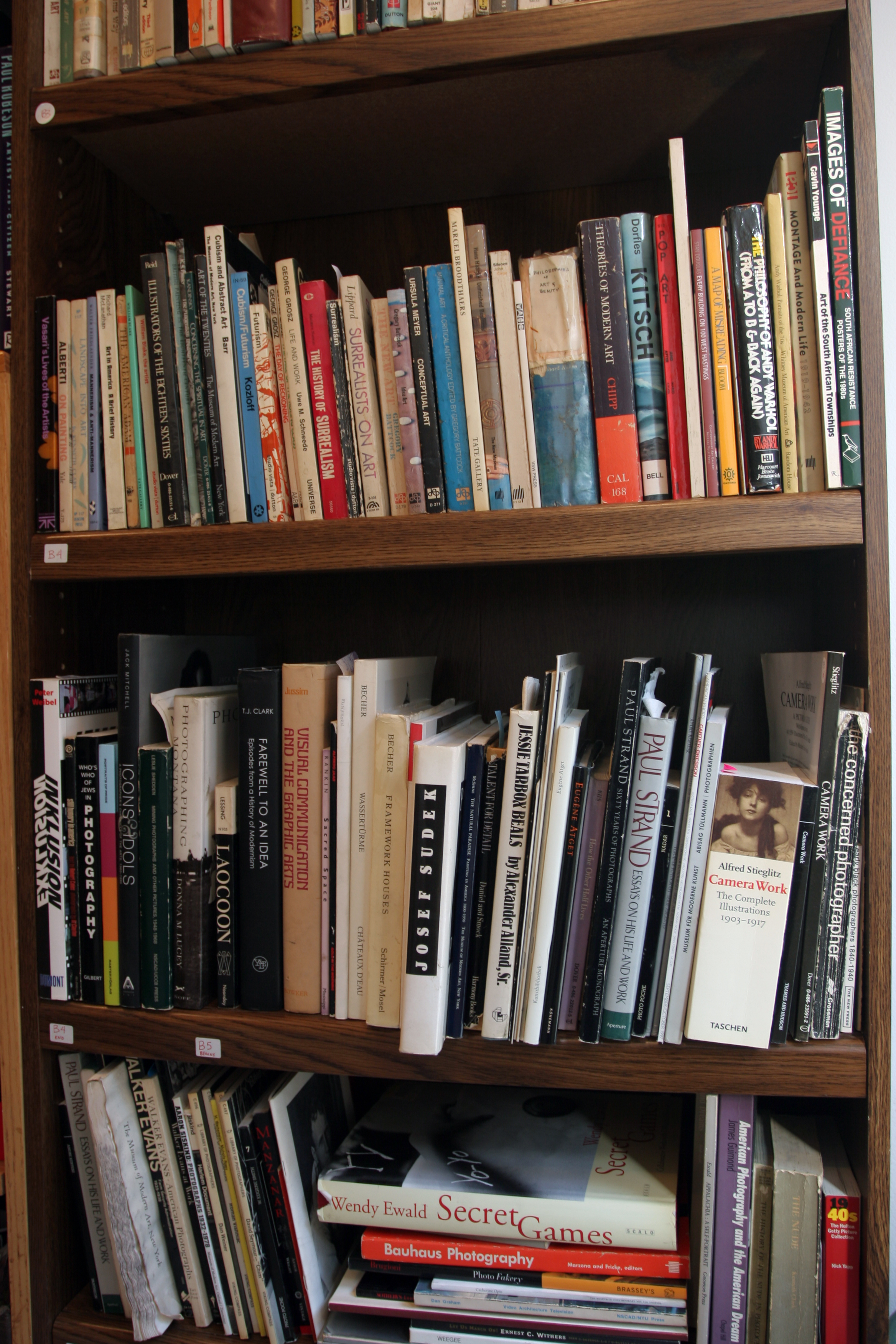

Martha Rosler Library: Comprising more than 7,000 volumes selected from the books at Martha Rosler’s residence and studio in Brooklyn and academic office in New Jersey, the library was accessible for the public use at e-flux’s Ludlow street location in NYC.

A personal library represents the private sphere of an individual, her way of acquiring and combining knowledge. Accumulation is the result of an intellectual inquiry that takes place in parallel with a more random search, which can lead us to unexpected textual, and therefore mental, spaces. Martha Rosler Library offers the visitor an opportunity to approach this open source of information with her or his own interests, and to create new affinities and connections between the elements of the library that add to more than the sum of knowledge contained in it.

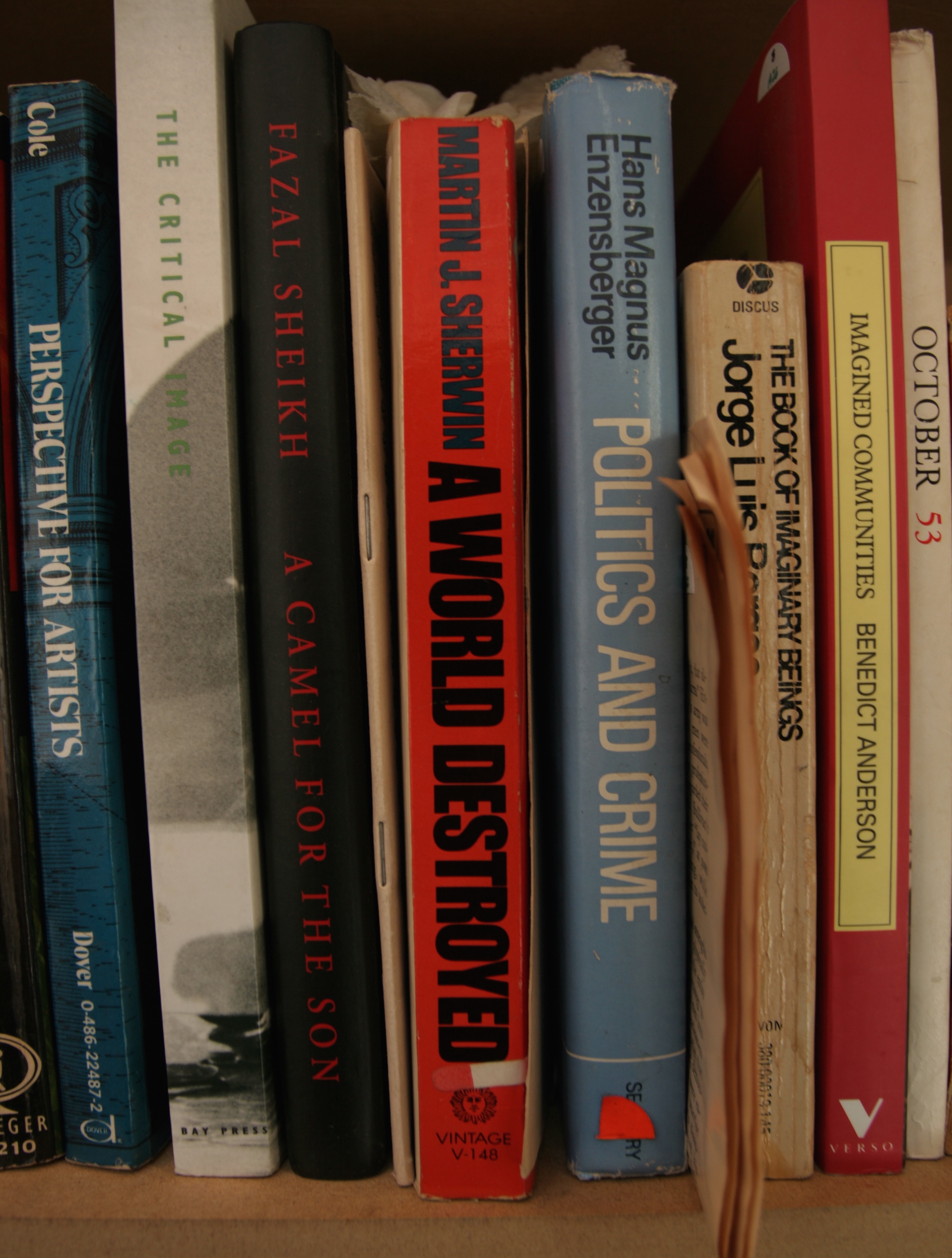

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at MUHKA Museum for Contemporary Art, Antwerp, 2006

Martha Rosler Library at MUHKA Museum for Contemporary Art, Antwerp, 2006

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library at e-flux storefront, New York, 2005

Martha Rosler Library was shown in the following venues:

e-flux storefront, New York, NY, 2005-2006

Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2006

New International Cultural Center (NICC) and Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA), Antwerp, Belgium, 2006

unitednationsplaza, Berlin, Germany 2007

Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, Paris, France, 2007-2008

Stills Centre, Edinburg, Scotland, 2008

Liverpool School of Art and Design, John Moores University, Liverpool, UK, 2008

Herter Art Gallery, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, 2009

Reviews

“If You Read Here... Martha Rosler's Library” • Elena Filipovic

The truth is, I can't help but begin by mentioning the toilet paper. All wrinkled and white, and rarely torn neatly across the perforated lines, toilet paper kept the mark of pages in many of Martha Rosler's books... A man's library is a sort of harem. - Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Conduct of Life (1860) The truth is, I can't help but begin b...

The truth is, I can't help but begin by mentioning the toilet paper. All wrinkled and white, and rarely torn neatly across the perforated lines, toilet paper kept the mark of pages in many of Martha Rosler's books...

A man's library is a sort of harem.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Conduct of Life (1860)

The truth is, I can't help but begin by mentioning the toilet paper. All wrinkled and white (none of the fancy double-ply lavender-coloured variety), and rarely torn neatly across the perforated lines, toilet paper kept the mark of pages in (dare I say?) many of Martha Rosler's books. These books - nearly eight thousand of them - were temporarily removed from the artist's home and shelved in impressive row after row in a cramped storefront space in New York's Lower East Side run by e-flux. There they stood, free and open to the public for months. The books were then packed and relocated to other venues, occupying reorganised rows in the Frankfurter Kunstverein and, later still, in a walk-up space in Antwerp as part of MuHKA's 'Academy, Learning from Art' exhibition.

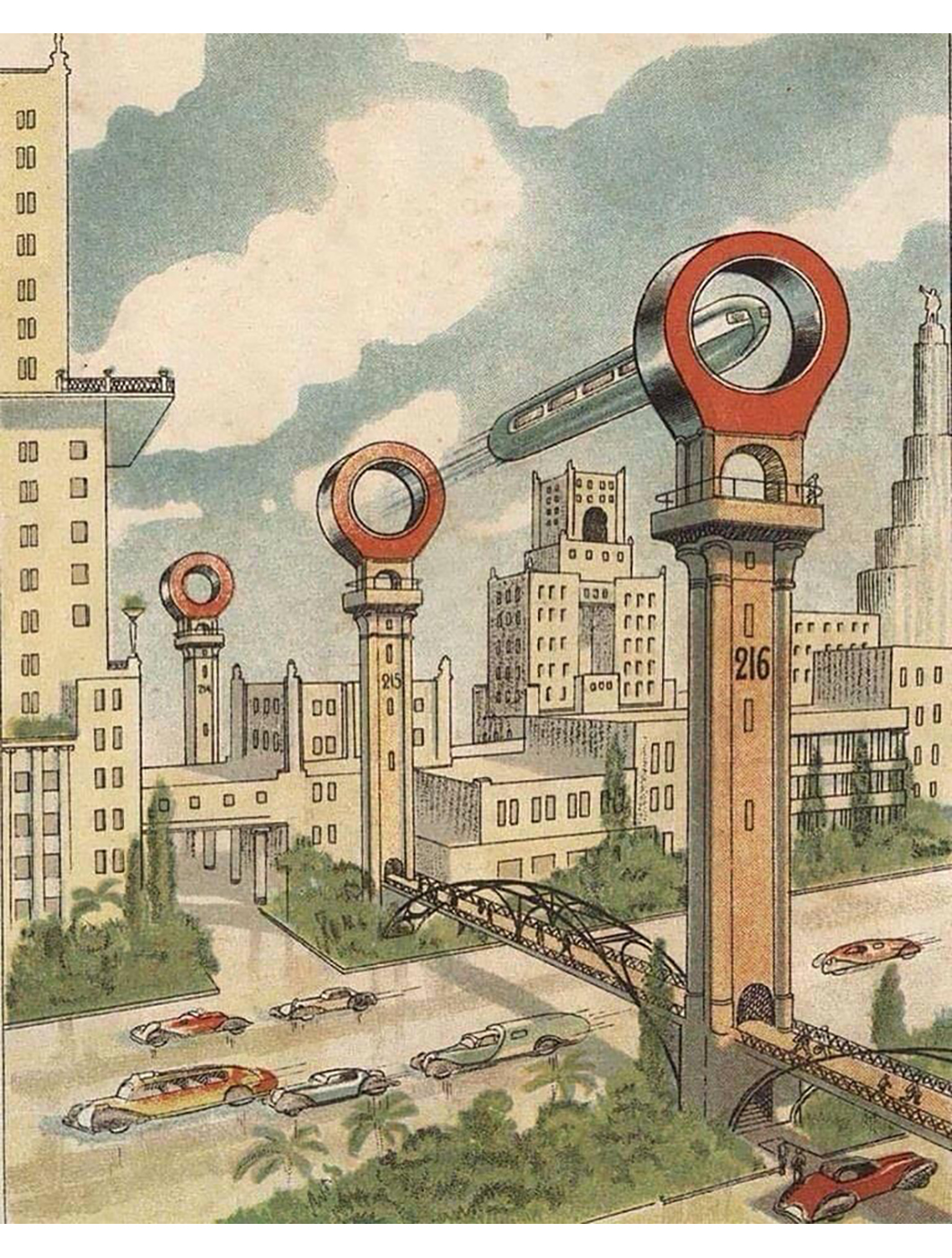

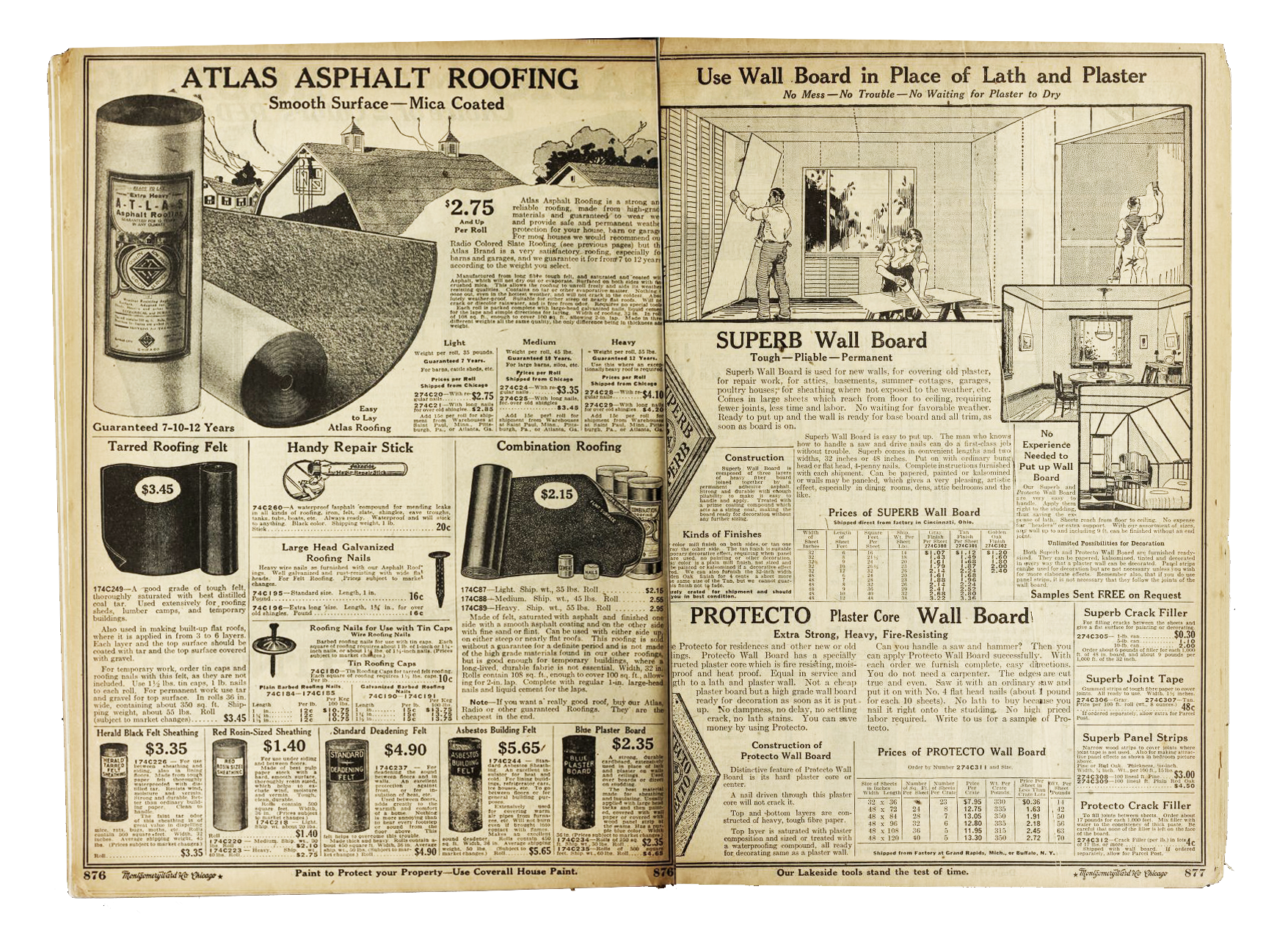

In an act of incredible generosity, one of America's most important living artists temporality dispossessed herself of the vast majority of her personal library so that it could be made available for consultation. No borrowing was possible, but the eclectic ensemble of books on economics, political theory, war, colonialism, poetry, feminism, science fiction, art history, mystery novels, children's books, dictionaries, maps and travel books, as well as photo albums, posters, postcards and newspaper clippings could be studied at will. Smart, decidedly political in orientation, often funny, and all over the place (in that way a perfect mirror of its owner), the library is packed with essential reading and titles that even your better bookstores would love to get their hands on. As the product of decades of avid reading, the contents of the library are both the source of Rosler's work and an installation/artwork that continues many of the concerns - with public space, access to information and engaged citizenship - that traverse her entire oeuvre.

The project started, its initiators insist, as the result of a 'space problem'. Rosler flippantly complained that her books were overtaking her house, a comment that led Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle of e-flux to ask her to consider displacing them temporarily as an art project. The idea came to Vidokle in part also as a riposte to the cool distance and lack of access he noticed in Donald Judd's library at Marfa, Texas. According to explicit estate decree, Judd's books can only be viewed behind glass, some volumes still in their unopened plastic wrappers, with absolutely no consultation allowed. The ensemble (in custom-built Judd shelves, of course) is less a library of its owner's thousands of volumes than a piece of Minimalist sculpture. A 'Martha Rosler Library' could thus serve as a living testament to another approach, one more fitting with her work and position as an artist. And it makes perfect sense since there is nothing beguiling or precious about anything Rosler does, and that is part of the point. Everything about her practice - from its workaday materials, its directness and its criticality - avoids the game of distance and seduction that she is precisely so able to critique. The temporary bequeathal of her library was no exception. No Minimalist mausoleum, Rosler's toilet-paper lined, user-friendly monument to feminism, to the political left and to her engagement as a citizen, an intellectual and an artist is more than the sum of her irregular shelves and books - it is a space for the public. For the 'Martha Rosler Library' also comprises a table, chairs, paper to take notes with, a free photocopy machine and the setting for reading groups and discussions - in other words, a space to cultivate discussion, debate and knowledge-production.

The toilet paper plays no small role in understanding all of this. There was something both terribly intimate and real-life about seeing it stuffed between all those pages. This was not an antiseptic, city- or university-run operation - this was someone's library, uncensored, unedited, without the kind of house-cleaning that left the dirty laundry outside of view. In your mind's eye you could see where the books had been (whether you wanted to or not), but also with what attention they had been perused, with what voracity and curiosity their owner-reader had collected them over the decades that their publication histories spanned, and finally what thoughts they made ricochet in their owner's head. For to look at the titles was to realise that the library was the active receptacle that for several decades Rosler's own work had been drawn from. Rosler's considerable reading is reflected not least in her prolific critical writings, which include countless essays and photo-texts and nearly a dozen publications that are inseparable confines of the art world. The resulting work is always political in nature and has, for nearly four decades, explored how socioeconomic realities, ideologies and sexual politics dictate our everyday life. Thus, in response to Ralph Waldo Emerson's idea of a library as an implicitly masculine domain and its books a willing flock of lovers, she might well respond that a woman's library is a sort of weapon, even as hers has been made available to the public so that it can willfully work against the idea that a library might be the rightful place of any one person, gender, class, race or kind. But weapon it is, standing against the amnesia of the past, the illiteracy of contemporary culture and the kind of thinking that made Emerson's comment a reality for far too long.

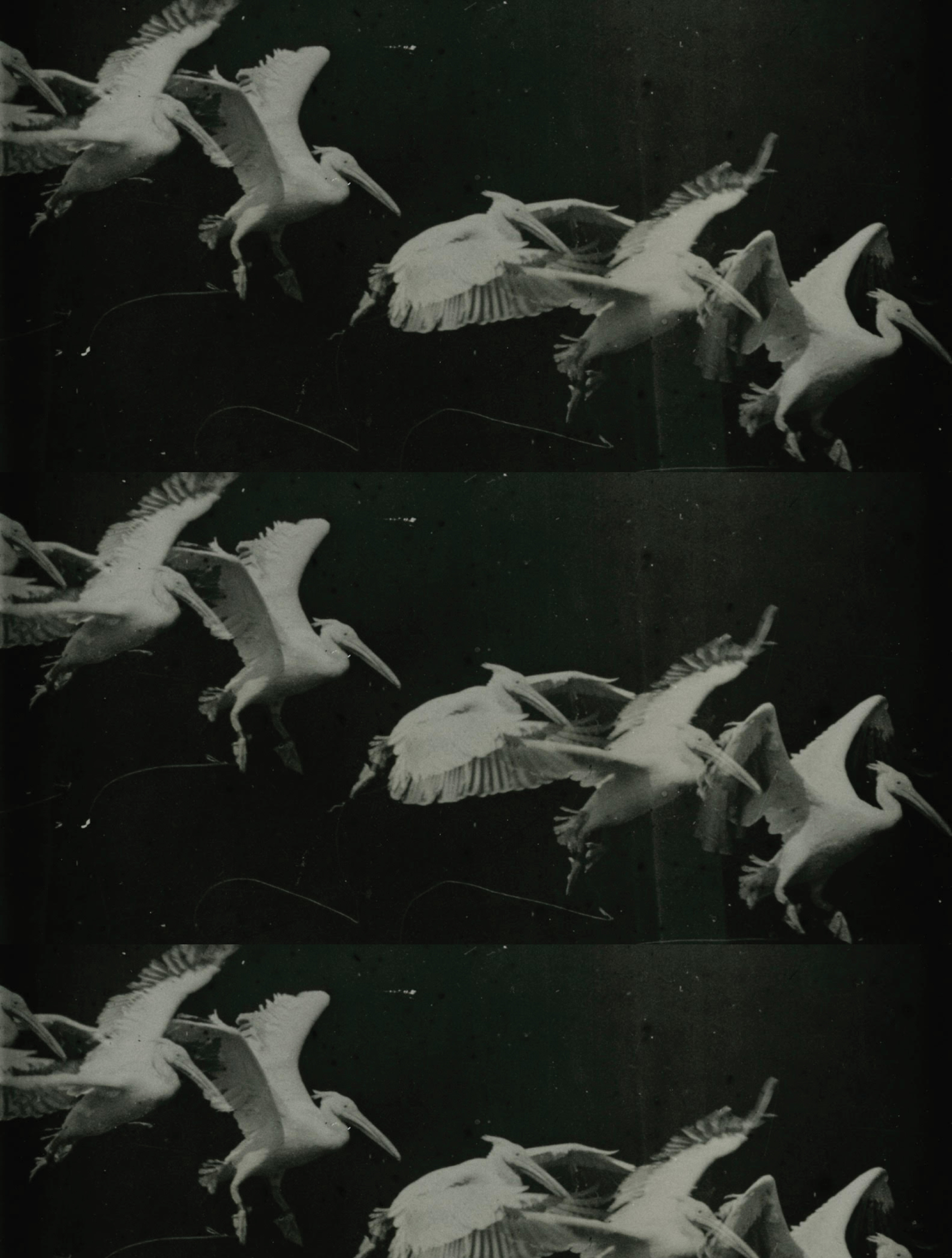

From her famous collage series Bringing the War Home (1967–72), culled from the pages of LifeHouse Beautiful, to her videos and various installations, so much of what Rosler has made involved printed matter as a direct resource. But more specifically, Rosler is amongst a rare breed of artists for whom reading - of the image, of the media, of books - is central. Think of those projects in which the deconstruction of the political ideology in the everyday is a dominant motif. Already in an early videotaped performance, The East is Red, the West is Bending (1977), Rosler reads aloud a booklet that accompanies a newly marketed consumer appliance, an electric wok. Revealing the nexus of imperialism, exoticism, sexism and class implicit in the corporate language that encourages female consumers to master foreign cuisines, her absurd cooking show already hints at the way that reading will continue to pervade her work. A decade later, in Born to be Sold: Martha Rosler Reads The Strange Case of Baby S/M (1988), Rosler, as the title suggests, reads for us. Her video analyses the class and gender bias of the mainstream media and court in a contemporary US legal case regarding women's reproductive rights.

Books have often been present in Rosler's projects, as has been the habit of rethinking the art exhibition as a form and as a public space. Think of her Monumental Garage Sale, first staged in 1973 in the Art Gallery of the University of California, San Diego. Visitors were invited to rummage through piles of second-hand goods - clothes, records, toys, personal letters, tchatchkas and, of course, books. Visitor-customers could bargain with the sales assistants and buy items displayed on tables that were sold over the duration of the exhibition. Part installation, part performance, part exhibition, it was originally advertised as a household sale in local newspapers but also as an art event within art channels. The fact that the sale was publicized in these two separate worlds - art world and 'real' world - meant that, like the library, Rosler hoped to attract and speak to an audience that wasn't uniquely a regular gallery-going public. For Rosler it was a project to make visitors of all walks of life 'think again about the structure of desire and possession in America'. What better way, after all, than a garage sale to interrogate art as commodity, the art institution as a place of unspoken sales transactions, the artist as a seller of fetishised goods, and economics as the determinant of social transactions? It also sent objects into the world that Rosler hoped in turn would help change it, however slightly; books were no negligible item in this equation, since the artist's selection was made up of writings by women that she hoped to circulate and make more widely available.

In the decade that followed, Rosler regularly made books available in reading areas that were integrated into her exhibitions. The first was her 'Fascination with the (Game of the) Exploding (Historical) Hollow Leg' (1983), an exhibition as packed as its title, with a simulated war room situated beneath giant cargo parachutes and lined with maps of US armed-forces deployments, nuclear-weapons manuals, recruitment posters, military uniforms, a slide show of US and European protest marches and posters, newspaper clippings, audio and video material and a library of books on war. Held at the Sibell-Wolle Fine Art Gallery in Colorado, it hosted a forum on activism and reading groups that met to read about World War II. Another project, even more ambitious, 'If You Lived Here…' (1989-92) was to homelessness what 'Fascination' was to America's Cold War paranoia. It consisted of a cycle of exhibitions, public forums, a publication and associated activities that Rosler organised as both participating artist and curator for the Dia Foundation in New York. The exhibitions featured the works of a slew of activist artists alongside graphs charting the city's housing shortage, newspaper articles on homelessness, photos of the homeless and devastated urban neighborhoods, make-shift shelters as well as shelves and tables lined with pamphlets and books.

Somewhere between activist reading rooms and installation-objects, these exhibitions introduced a tension between public reading and a space for art, a tension explicitly directed against the passive, contemplative visual habits that art displays typically reinforce. For, it must be said, reading (apart from wall text) doesn't usually happen in art exhibitions. In such bastions of the visual, the textual is typically relegated to the margins - hallway, exit area, bookshop. But for Rosler, rather than thinking of the museum or gallery as an antiseptic, isolated, neutral space of contemplation with artworks as either dead specimens or receptacles for illusions, she shows us instead that the artwork is a 'text' to be read, and that the exhibition can be a place for engaged reading. The walls of her exhibitions often serve not as mute frame, but as part and parcel of the artwork - painted on, they become the support for slogans, citations - in short, for more reading. It is more than fitting, then, that Rosler's interest in reading should coalesce into a project that constructs a public space where people can sit, read, photocopy and peruse with no order imposed and no authority in sight. The 'Martha Rosler Library' is the logical continuation of her practice, and yet another way by which she continues to defy the protocols for the display of art. Unlike, for instance, Carol Bove's sculptures, in which book pages are left open but kept away from the hands of the viewer, and where meaning is suggested through the relay of references and formal geometries of untouchable books on a shelf, or Allen Ruppersberg's facsimile books and blank-paged book-objects available for consultation only if handled with care, the 'Martha Rosler Library' resists behaving like 'art'.

The library is the first of Rosler's projects in which reading isn't the contextual background or component to something larger, but is the project. And for this, organisation is paramount. The displaced library originally followed the logic of the shelves in Rosler's own Greenpoint, New York home. For instance, books lining the individual stairs of her home were gathered and placed on corresponding shelves in the e-flux space, as were books from the hallway, the bathroom, the office, etc. Thus their organisation was one of use and practicality, a homespun logic that nevertheless reveals Rosler's ideas and positions on publications that make sense together. This shifted when the library was moved to Frankfurt and Antwerp, because in each case new spatial conditions (and new interpretations of Rosler's organisational universe by herself or others) help determine its form.

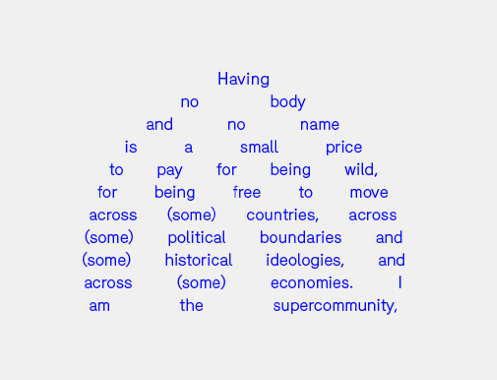

MuHKA curator Dieter Roelstraete calls it a library that follows a 'domino theory of history'. And indeed a look at its offerings shows, as he suggests, that the section with literature by women leads to books on feminism leads to gender studies leads to family studies leads to psychoanalysis leads to Jewish studies leads to books on the Holocaust which leads to German history, and so on. And in its shelving and re-shelving, the 'Martha Rosler Library' reorganises the history of the world and makes us sensitive to the way the presentation of that thing we call 'history' matters. Libraries, after all (and this library reminds us of it), not only store but also participate in the production of history. They beg the question of the ideologies they promote and the roles they fulfill in the process of truth-production. While the library isn't Borges's Chinese encyclopedia, it employs a taxonomy that doesn't quite follow the Dewey decimal system either. And just as Foucault claimed of Borges's fictive encyclopaedia's incomprehensively wild taxonomy that it allowed one to apprehend 'the exotic charm of another system of thought' as well as 'the limitation of our own', so does Rosler's personal system of order and classification beg us to attend to the rules that govern our own positions. Her library is a world picture - one in which women are prolific science fiction writers, the political Left has a voice, 'marginal' cultures have a place, colonial history is not forgotten and feminism didn't begin and end in the 1970s.

Rosler might just tell you that it is another one of her 'decoys', and that her work is a series of them - one thing camouflaged as another so that 'the more you look at it, the more you see that it's asking you to think about something else'. About this Roelstraete recounted an anecdote that speaks volumes: after arranging the library for its Antwerp presentation, Rosler lamented that a section of writings about black history found itself tucked on a shelf in a corner. It would have to be moved, she insisted, black history could not be marginalised further. Rosler's attention to the position and placement of the books is a key to understanding the library. Like Foucault's concern with the mechanisms by which power 'reaches into the very grain of individuals, touches their bodies and inserts itself into their actions and attitudes, their discourses, learning processes and everyday lives', Rosler offers readers off the street the free use of a library that refuses to reproduce the hegemonic positions of our present and indeed begs us to think about how they function in our everyday. And therein lies one of the library's most critical roles and its conceptual connection to so much of the artist's larger oeuvre.

The gaps in the library (Rosler held back several thousand books that she was convinced she might need to consult) suggest something of its necessary incompleteness and fragile claim to anything like absolute authority, pointing at one of the important questions of the project: within this sanctuary to the author and to authorship itself (what more likely a place to ask such a question than a library of books) - who is the author? Its very title heralds some of its expiation of authority and its willful ambiguity as a library-cum-artwork. The project is, after all, the 'Martha Rosler Library'. Not 'The Martha Rosler Library'. The difference is small but significant. And, as Rosler is quick to point out, the former is incorrect grammatically speaking. So what happened? The artist did not give the project its title, and she didn't insist on a change when she was confronted with it. Had Rosler named the project, she might have given it another name (and perhaps not one with her name in it at all), she easily volunteers; or, at the very least, she would not have left off the definite article that its Mexican and Russian-born e-flux initiators (Aranda and Vidokle, respectively, both artists themselves) did. But the 'error' is perhaps no mistake, for in that lies a clue to the complexity of this project that sits between a functional space/service and an artwork in which Martha Rosler, the proper name, abandoned authority so that we could sit, read and make of her books what we will, toilet paper and all.

“Better Read Than Dead: a Visit to the Martha Rosler Library” • Graeme Thomson and Silvia Maglioni

Parisian book-lovers peeved at the frosty reception and draconian security arrangements of the Bibliothèque nationale de France can, for a limited time, take solace in the somewhat cosier nook provided by the Martha Rosler Library, installed in the Galerie Colbert (Institut national d’histoire de l’art) until Jan 20 as part of a travelling exhibition project...

Parisian book-lovers peeved at the frosty reception and draconian security arrangements of the Bibliothèque nationale de France can, for a limited time, take solace in the somewhat cosier nook provided by the Martha Rosler Library, installed in the Galerie Colbert (Institut national d’histoire de l’art) until Jan 20 as part of a travelling exhibition project. The choice of reading matter may not be quite so vast, but visitors are at least free to finger the spines, delve into and even photocopy pages from any of the library’s 7,600-odd volumes, periodicals and catalogues, many out of print, some quite rare, on subjects ranging from Marxist theory to heraldry, cinema to cookery, Situationism to pattern making.

According to art theorist Stephen Wright who welcomes visitors to the space, Rosler has read most if not all the books in her library, which over the years has served as both ideas bank and toolbox for her radical mixed-media art interventions: from witty critiques of the commodification of women and anti-war photo-montages to her more recent investigations into the living conditions of the poorest, most marginalised sectors of society.

The project’s curator, Anton Vidokle of e-flux, explains how the idea for the library initially came from his reaction on visiting the Donald Judd library in Marfa, Texas whose some 10,000 volumes were, according to a clause in the artist’s will, to remain as he had arranged them, undisturbed, on shelves and tables he had himself designed and built. Under the immaculate surface abstraction of their meticulously arrayed covers, many still in their shrinkwrap packaging, some simply embalmed in the stillness of dead time, the books’ contents were slowly crumbling to dust. Vidokle recounted his impressions to Martha Rosler (whether the slippage from Marfa to Martha was part of the game plan he doesn’t say) who also possessed a sizeable library but whose problem was of a somewhat different order – she had quite simply run out of space. So Vidokle proposed borrowing Rosler’s collection to install in e-flux’s Ludlow St. Art Space in New York as a fully functioning reading room. Rosler accepted the proposal and the Martha Rosler Library was born.

The name itself (not Martha Rosler’s library but the Martha Rosler library) gives some indication of the library’s playfully ambiguous status and of the visitor’s uncertain relation to it. While there is the temptation simply to use the space for personal study or relaxation, pretend for a few hours that it really is a library, the notion of it being also an “art project” makes the library equally something we are summoned to survey, interpret or read in some way, an urge which inevitably cuts across its proposed functionality. While the formality of the name might suggest a disinterested bequest, “Martha Rosler” as sign and symptom of a particular order and distribution, not to mention “ownership” of discourse, a particular memeplex, keeps getting in the way of any common (commons) reader’s agenda, just as the constant background “dumbiance” of National Public Radio, which Rosler apparently has on all the time at home, persists as index of the artist’s phantomatic self-presencing. As a result of this, and also because of the deception the installation perpetrates in posing as a more permanent structure, one you imagine returning to again and again, feeling it will continue to exist into the foreseeable future, the Rosler library continues to oscillate, one might even say flicker, imperceptibly between public and private domain, a tremor that makes concentration, whether as reader or viewer, difficult.

You would think these tensions might provide an interesting topic for debate among tarrying wayfarers. Unfortunately, the reading room risks reproducing the same kind of silence and self-enclosure, at least among adult visitors, that one normally finds in a reference library: its potential for renegotiating the meaning and function of the library as “public” space is undermined from the outset by a self-policing that invests the private body politic and which it seems no longer needs to be enforced or even administered. What is surprising is that while an opportunity clearly exists here (as it does to a lesser degree in any library or bookshop) for the public to engage more directly with the space, insinuating messages and letters between the covers, bookmarking pages as a sign of their passage, weaving a clandestine narrative of cryptic traces, few are sufficiently emboldened to put it into practice. Before we can create more open, communitarian spaces, we need more radical, relational bodies.

“Who Needs A White Cube These Days?” • Roberta Smith

"WHAT is art?" may be the art world's most relentlessly asked question. But a more pertinent one right now is, "What is an art gallery?" It is heard often these days, and within it lies another question: do galleries have to run or look the way they do? How inevitable is the repeating cycle of solo and group exhibitions and the steady movement of artworks...

"WHAT is art?" may be the art world's most relentlessly asked question. But a more pertinent one right now is, "What is an art gallery?"

It is heard often these days, and within it lies another question: do galleries have to run or look the way they do? How inevitable is the repeating cycle of solo and group exhibitions and the steady movement of artworks from galleries to museums, auction houses and collectors' homes? How can you slow, expose or disrupt the delivery mechanism -- maybe even avoid it altogether occasionally -- to reassert art as a process and a mind-set rather than a product?

With their changing exhibitions and precarious finances, galleries are by definition fluid forms, under constant revision. But lately the gallery model has seemed even more in flux than usual. More young dealers, artists and people who are both (or neither) are thinking outside the white cube. Other galleries are trying to brake their ascent to establishment status by interrupting the flow of monthly shows and finished objects, substituting a monthlong presentation of short exhibitions and even shorter performances.

Some established dealers turn their spaces over not to independent curators but to other dealers. As Mary Boone, queen of the 1980's art scene, explains on Artforum.com, she commissioned Jose Freire, who owns Team Gallery in Chelsea, to organize two group shows in her 57th Street space because she was interested in "giving my old career new life." But the real new life may be coming from further down the food chain, from individuals and groups who often operate in the gap between traditional galleries and alternative spaces. Their vocabulary -- "transparency," "modes of attention" and "the rhetoric of display" are often tossed about -- suggests a reaction against the art-as-product orientation habitually ascribed to the Chelsea scene. But they also benefit, themselves, from the surplus of disposable income that flows through the gallery system.

There are precedents for the latest round of what might be called deviant or alternative galleries. One is 112 Greene Street, the freewheeling artist-run exhibition space of early SoHo. Another was American Fine Arts, the sometimes anarchic gallery that Colin de Land and his artists oversaw on Wooster Street in SoHo, and then in Chelsea until his death in 2003.

A more recent precedent is the Wrong Gallery, created by the artist Maurizio Cattelan and the independent curators Ali Subotnick and Massimiliano Gioni. It opened on West 20th Street in 2002, in a one-foot-deep doorway behind a glass door identical to the one leading into the adjacent Andrew Kreps Gallery. Modestly but memorably, Wrong demonstrated that it was possible both to parody a gallery and function as one, giving numerous artists mini-debuts.

The 20th Street doorways (there was briefly a two-feet-deep annex) have closed, but Wrong will participate in this year's Whitney Biennial, and began an extended stay at Tate Modern in London in December. The Wrong Gallery creators are currently in Berlin organizing the Berlin Biennial for March: as part of the show, they have created Gagosian Gallery, Berlin, a real gallery that so far has put on four exhibitions. Any resemblance to the real Gagosian Gallery, or the Guggenheim Berlin, is not coincidental.

One oft-cited precedent is still active in New York: Gavin Brown, who stirred up the gallery form in the mid-1990's by opening a bar called Passerby nearly inside his gallery on West 15th Street. (They shared restrooms.) Two years ago Mr. Brown relocated his main gallery to Greenwich and Leroy Streets, maintaining Passerby (run with a partner) and keeping his old gallery as an intermittent off-site project space. The Leroy Street space is beginning the new year with a series of one-week shows, starting with "Sonic the Warhol," a film by Oliver Payne and Nick Relph that combines video game faces with a visit to the zoo: everyone gets a mask, and the music, by Brian DeGraw, is terrific.

Subversion and Survival

In some ways, Michele Maccarone has strayed furthest from the white cube. The three-story building she opened on the east end of Canal Street in 2001 is barely renovated, and she has allowed it to be regularly torn up, top to bottom, by artists showing there. But Ms. Maccarone is in other ways an old-style gallerist, who seems to have almost single-handedly willed her challenging project into existence while always striving to meet the demands of her artists.

Her current exhibition, the overstocked debut of Nate Lowman, demonstrates the way all galleries fluctuate between subversion and business as usual, if only to survive. In the show, titled "The End and Other American Pastimes," Mr. Lowman continues to develop his down-and-out excursions into collage, graffiti and appropriation. The work feels original in some places -- especially a painting technique that suggests velvety silkscreens -- and tried-and-Warholian in others, like the series of paintings of blown-up fake bullet holes, which take up a great deal of wall space throughout the building.

In contrast to nearly everything about Maccarone except its funky space, there is Reena Spaulings, a two-year-old gallery, (now on winter hiatus) headed by a nonexistent person, that happened largely by accident. In a small storefront on Grand Street, overseen by Emily Sundblad, a Norwegian artist, and John Kelsey, an American critic, the operation has provided an adamant reminder that a gallery is a social organism -- even a kind of family -- that combines aspects of living room and studio.

The space, part of the housing complex where Ms. Sundblad lives, was initially rented to create a business address that would beef up her visa application, and grew from there. The Reenas, as they are sometimes called, left in place a delicate pipe scaffolding from the store's days as a dress shop; it now serves as a brilliant device to disrupt the gaze and usually helps pull even the most shambling exhibition together.

The store was initially used, unnamed, as a meeting place, performance space and screening room. The fictional name came later, as did more organized exhibitions, but the unfinished air persists. Eventually, Ms. Sundblad and Mr. Kelsey started making art as Reena Spaulings, and she, as it were, has been invited to the 2006 Whitney Biennial, as has Josh Smith, a Spaulings artist.

Making It Transparent

While the use of a fictive character undermines the myth of the all-powerful art dealer, there is also a certain coyness to it. In contrast, at Orchard, the intellectually inclined new collective gallery that opened on Orchard Street last spring, total transparency is the goal. It is self-evident in a design that involves exposed wall studs and a desk that is actually a picnic table; it is also evident in the decision-making process.

At Orchard everything is hashed out by the collective's 11 members, which also tends to expose the secret emotional life of galleries, where ambition, idealism and vulnerability intersect and conflict. A debate about building storage shelves, which would hide things (diminishing transparency) but make life easier, was fierce. The members are still hashing out whether the gallery should stage solo shows.

Members are the artists Moyra Davey, Andrea Fraser, Gareth James, Christian Philipp-Müller (all formerly of American Fine Arts), Nicolas Guagnini, R. H. Quaytman, Karin Schneider and Jason Simon, as well as Rhea Anastas, an art historian ; Jeff Preiss, a cinematographer and artist; and John Yancy Jr., a computer programmer.

Mr. James has organized the gallery's current exhibition, "Painters Without Paintings and Paintings Without Painters," a feisty but rather beautiful assembly of mostly two-dimensional work that attacks and celebrates painting, or more precisely pictoriality, from all different angles.

The show includes a luminous Mondrianesque wall painting by the Scottish artist Lucy McKenzie; works by J. St. Bernard, a fictive artist who many believe was initiated by Colin de Land as well as Reena Spaulings; and one of Daniel Buren's striped-awninglike paintings, from 1972. History is also recalled in a wonderful homage to Cézanne from the often sardonic Jutta Koether and in works by Simon Bedwell and John Russell, two former members of the art collective Bank, which operated a studio/gallery in London in the 1990's.

Nothing for Sale

The gallery form has almost nothing to do with Scorched Earth, although in some ways it is the most white and boxy of the spaces below Grand Street. Around the corner from Orchard on Ludlow Street, it was cooked up by Mr. James and the artists Cheyney Thompson (who has two works in the Orchard show) and Sam Lewitt. It is a yearlong consideration of drawing in all its permutations, present and historic, and was inspired partly by frustration with the medium's current market popularity.

Its founders call Scorched Earth an editorial office whose chief goal is the publication of a magazine, not exhibitions. With purposeful disregard for usual periodical practice, its first and only 12 issues will be worked on over the next year and then published all at once.

Further liberties are being taken with the gallery form at the Martha Rosler Library, a tiny storefront resembling a used bookstore, where nothing is for sale. Crammed into creaky shelves are about 6,000 books owned by the artist eminence Martha Rosler -- on art, architecture, science fiction, poetry, history and beyond -- that form a kind of portrait of the artist's mind. Anyone can come in, browse, read and even photocopy a few pages -- free.

This functioning bibliographic tribute has been organized by the artists Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle, owners of e-Flux, a digital information service whose clients include about 400 art galleries and institutions worldwide. Their first project in the space was a free video rental, 500 videotapes by 250 artists, that ran for six months.

Mr. Vidokle calls the library "a useful resource that doesn't have any commercial motivation" and cites as inspiration the former artist-run SoHo restaurant FOOD, an offshoot of 112 Greene Street, where diners paid what they could.

Easier Said Than Done

It is difficult to be a full-service gallery and maintain a high degree of deviation for long. Friedrich Petzel, who took over the Printed Matter space next to his gallery on West 22nd Street, spoke in September of using it without benefit of a white-box redo or a set schedule. But by December, both were nearly in place, Mr. Petzel said, largely because of pressure from his artists.

When Andrew Kreps lost the lease to his 20th Street space last summer, he moved temporarily to a raw three-floor wedge of a building on 21st Street. While also staging solo shows, he enlisted one artist, Matt Keegan, to organize two excellent group shows, and another, Fia Backstrom, to set up a series of events, "Herd Instinct 360degrees," on the subject of community (the last of which, a panel, is on Jan. 22). The current exhibitions, of work by Roe Ethridge and Adam Putnam, are well worth visiting, but the space is also notable on its own. As downtown Manhattan and its art world both barrel ahead real estate-wise, it feels a bit like a relic from another time or place.

By March Mr. Kreps should be ensconced on West 22nd Street in the gallery previously occupied by D'Amelio Terras, which is relocating to larger quarters on the block. "I'm tired of roughing it," Mr. Kreps said, noting his current building's iffy heat.

Daniel Reich, another Chelsea dealer, has opened a second space at a place that so far seems inured to gentrification: the Chelsea Hotel. Called Daniel Reich temp., it will reopen in March with a group show organized by Nick Mauss.

But even the folks at Reena Spaulings admit that their artists want big careers and that they were impressed by the activities of deliberate, rather than accidental art dealers while participating in the Liste art fair in Basel, Switzerland, last spring. At Orchard, an invitation from Extra City, a fair starting in Antwerp, Belgium, is under consideration.

Dealers regularly move up the food chain, beyond "starter" galleries; witness the seven who just graduated to sleek ground-floor spaces on far West 27th Street in Chelsea. For those who want to start really small, the Wrong Gallery (in concert with Cerealart Inc.) is issuing a multiple: a 1:6 scale miniature version of its original door and doorway titled "Now Everyone Can Be a Dealer."