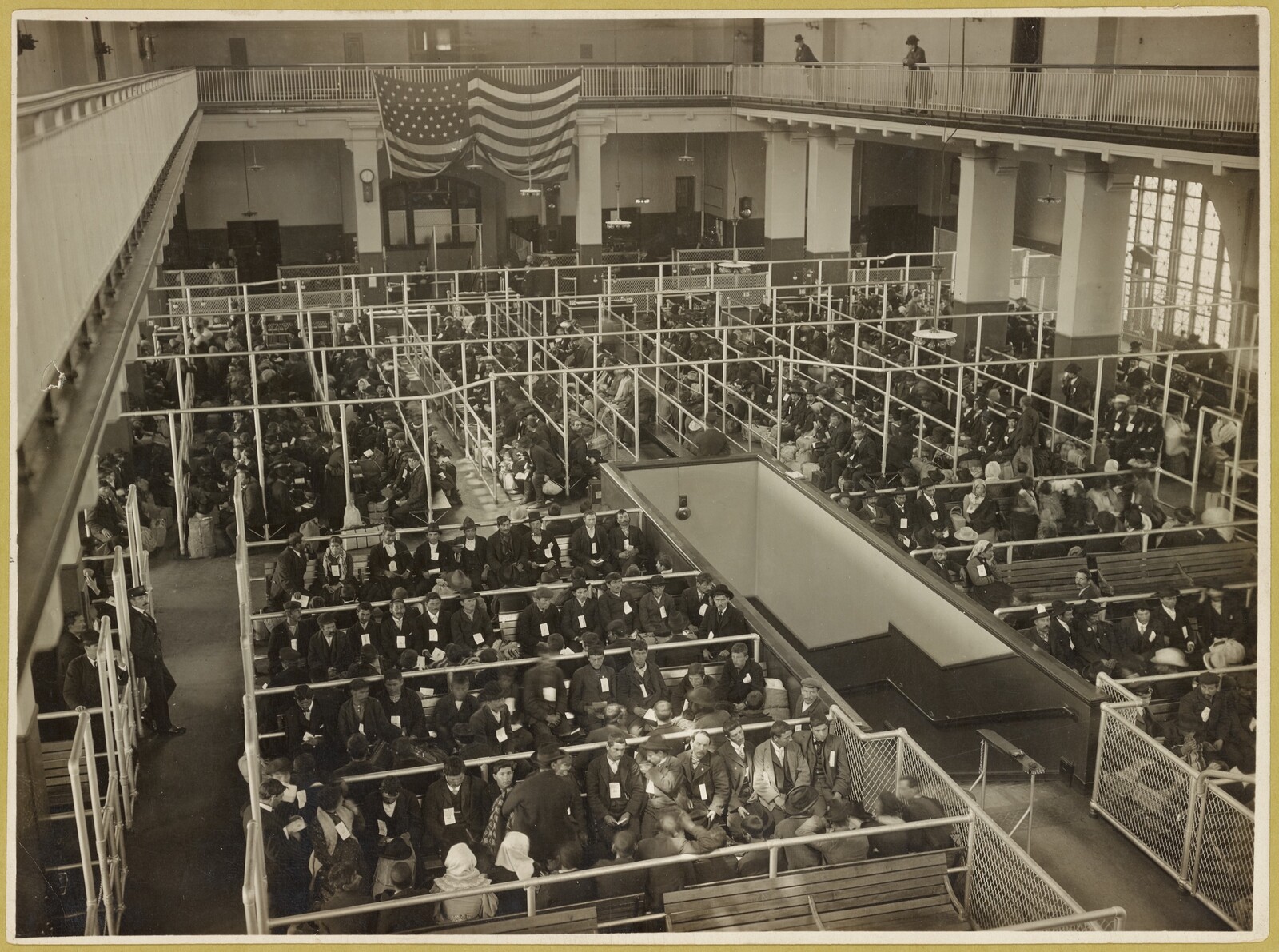

In 1975, tired of its reputation for being a “soft state” blemished by charges of corruption, security threats, labor unrest, and uncontrolled poverty within a rapidly growing population, the Indian Government of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency.1 With the suspension of citizen’s democratic and institutional rights, Gandhi laid forth in a number of speeches a new, paternalistic vision for the Indian nation—one that claimed to act in the people’s best interests, even if it acted alone. For Gandhi, independence from colonial rule meant an “opportunity to do our duty.”2 This duty mirrored the message of the 1970 film Housing for the People, which depicted the creation of a modern India, complete with “neat homes, neat citizens.”3 Produced by the Films Division of India, the media arm under the Ministry for Broadcasting and Information, the film was one of the many documentaries that carried a message of postcolonial nation-building—the eradication of poverty, pollution, and overpopulation, and uplifting those who had remained, according to Gandhi, “oppressed for centuries”—through modernization.4 Population and poverty were intertwined and broadcast through Government media such as this, as was the Prime Minister’s slogan, “garibi hatao” (“remove poverty”) that foregrounded population control as a prerequisite for social mobility and economic development.

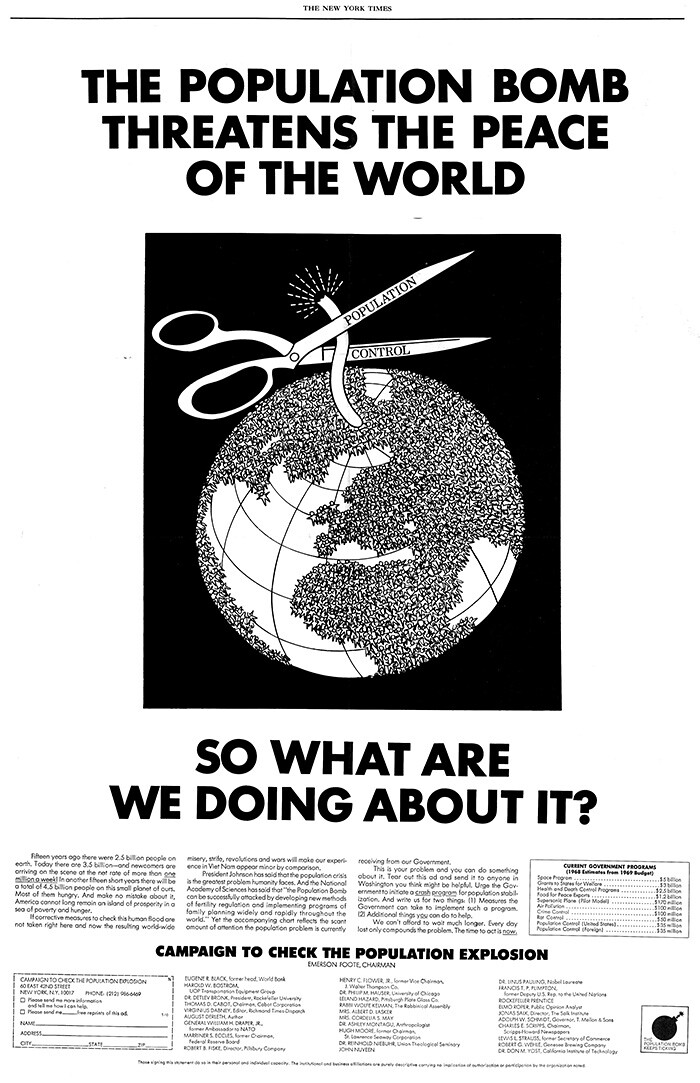

The 1970s was also a time when Euro-American environmental consciousness focused on the threat of overpopulation. Popularized by publications such as Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog and Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, “overpopulation” and “population control” moved into the remit of state politics. Succumbing to racial and neo-Malthusian discourse that described much of the poverty-stricken third world a threat to “planetary” health with its “unsustainable” fertility rates, these environmental movements focused on the fragility of life on “Spaceship Earth” and its imminent prospects of resource scarcity and limited “carrying capacity.” The 1970 UN Conference on Human Survival, for instance, attended by architects like Buckminster Fuller, was one of many gatherings organized to “examine the human condition in a world which has become a single geographic community and in which the principal problems have to do with the survival of the human species itself,” and where the “problem of the environment” was identified to be compounded by the “population problem.”5

From its origins in the 1950s, family planning in India was seen as crucial to the state modernization project, whose stated goals included poverty alleviation and economic growth. Guided by the sustained efforts of American and British birth control activists, the Ford Foundation, the United Nations advisory missions for demography, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), the Rockefeller Foundation, and USAID, by the early 1970s Indian family planning efforts had provided a gamut of contraceptive services to over ninety million people in the reproductive age group.

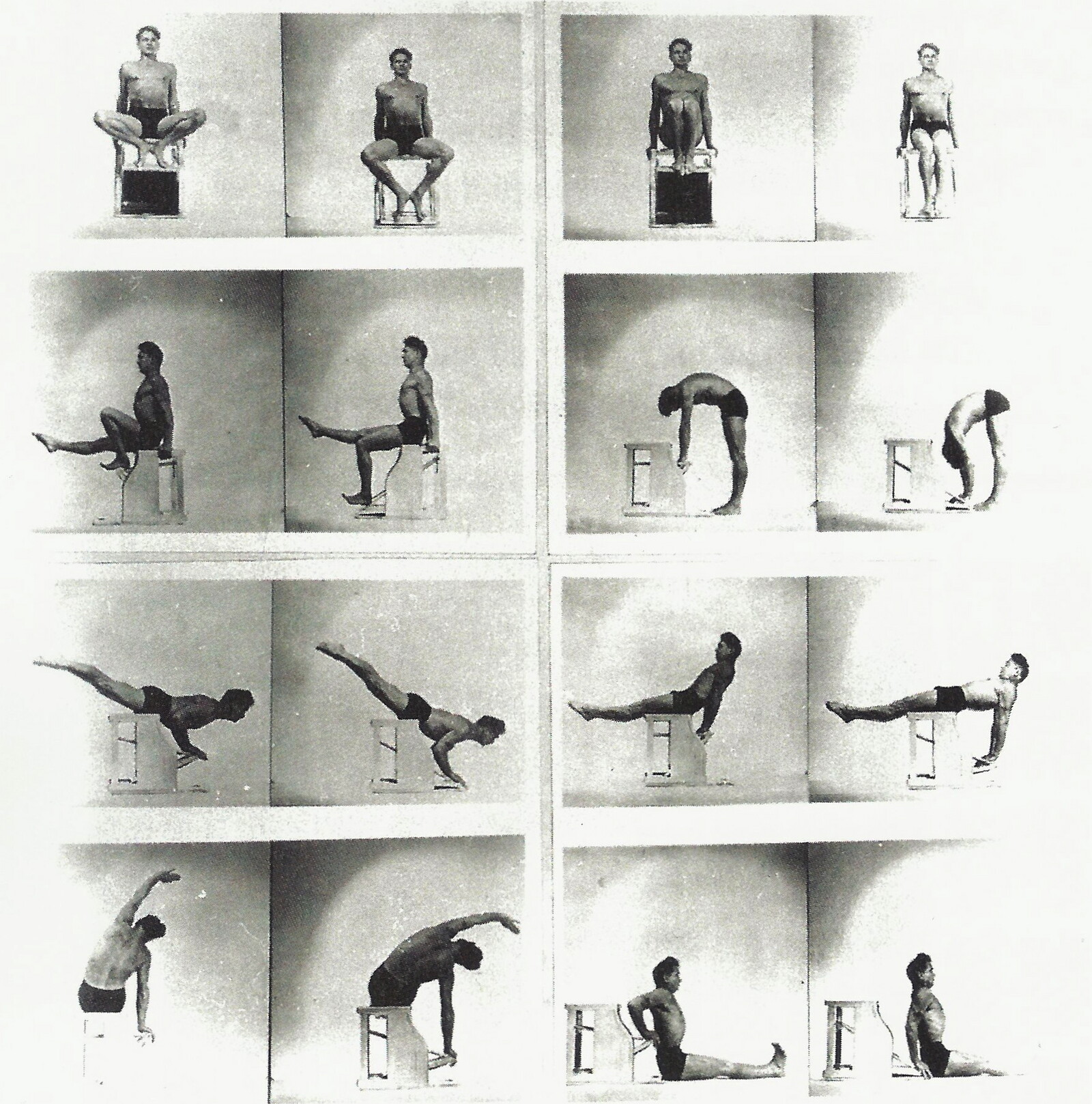

Family planning was originally marketed and rolled out as a voluntary system—with mobile health and education services that travelled from village to village to preach an optimum family size and extensive mass media campaigns that flashed positive, easily understandable messages on contraception through the press, radio, television, films, folk songs, drama parties, puppets, exhibitions. An overabundance of birth control propaganda took hold of the built environment in the 1970s, marked by an inverted vermillion equilateral triangle with the slogan “Do Ya Teen Bacche, Bus” (“Two or three children… stop”). Influenced by the aims of a growing environmental movement that saw resource security as essential to the growth of the nation, family planning in India soon became linked to a question of who was allowed to reproduce, with an eventual escalation of coercive tactics. From April to December of 1976, over seven million sterilization surgeries were involuntarily performed on both poor men and women.6

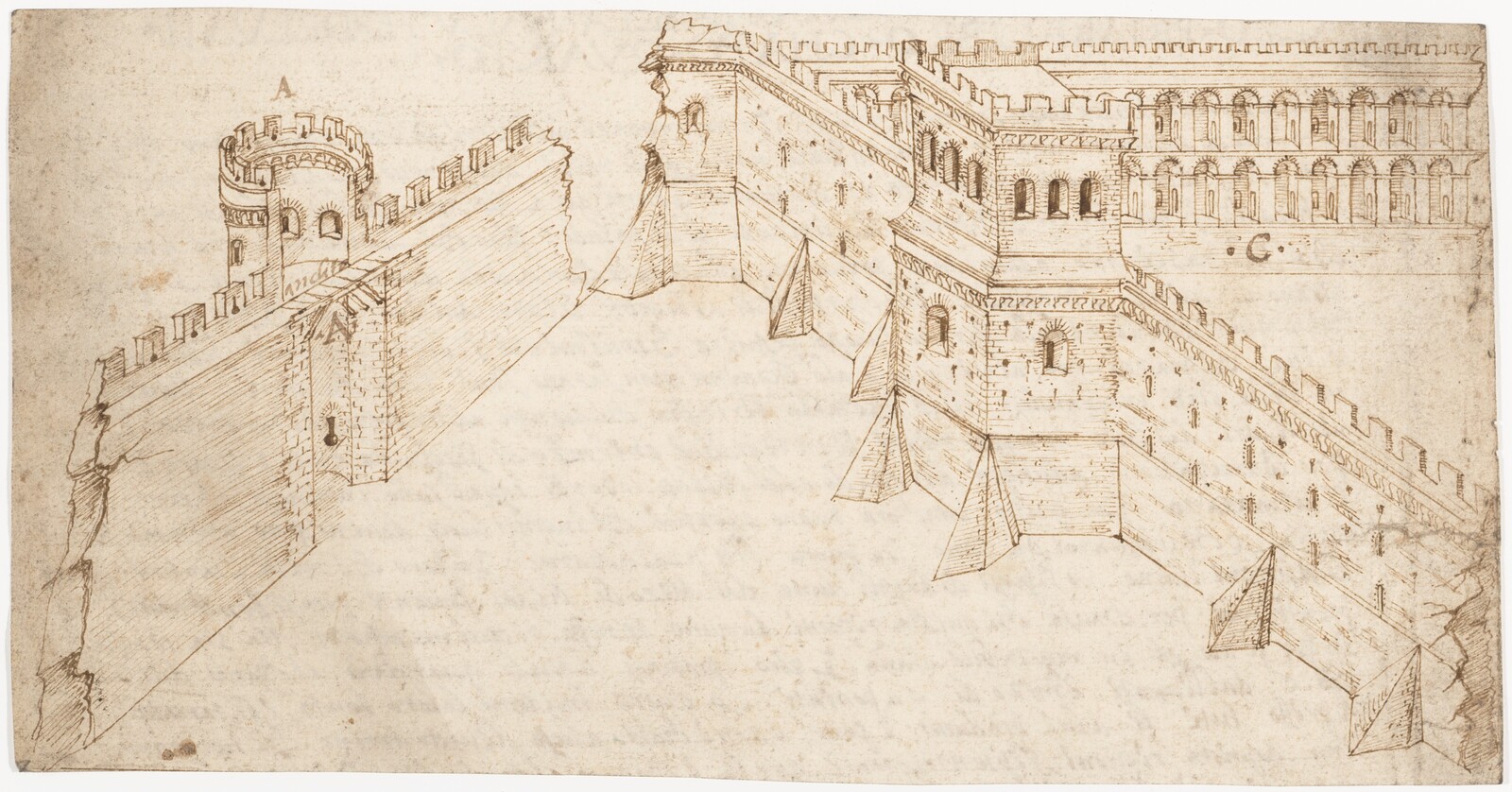

But family planning services could only be part of the “solution.” If mankind’s “disruption of the functioning environment” was identified as a serious concern for the continuation of life on earth, technical aid saw planning and development as a necessary tool to determine and implement the spatial constraints that would most effectively govern unwanted reproduction.7 Indeed, family planning programs cannot be assessed independently from the Indian Government’s formulation of housing policies, urban planning schemes, forced relocation schemes, and slum demolition proposals. With an escalation of coercion and violence in the implementation of fertility policies in poorer populations, technocratic planning to quell overpopulation-induced poverty meant finding solutions for housing the poor. Government officials not only attempted to perforate the sanctity of the body, but also the sanctity of the home.

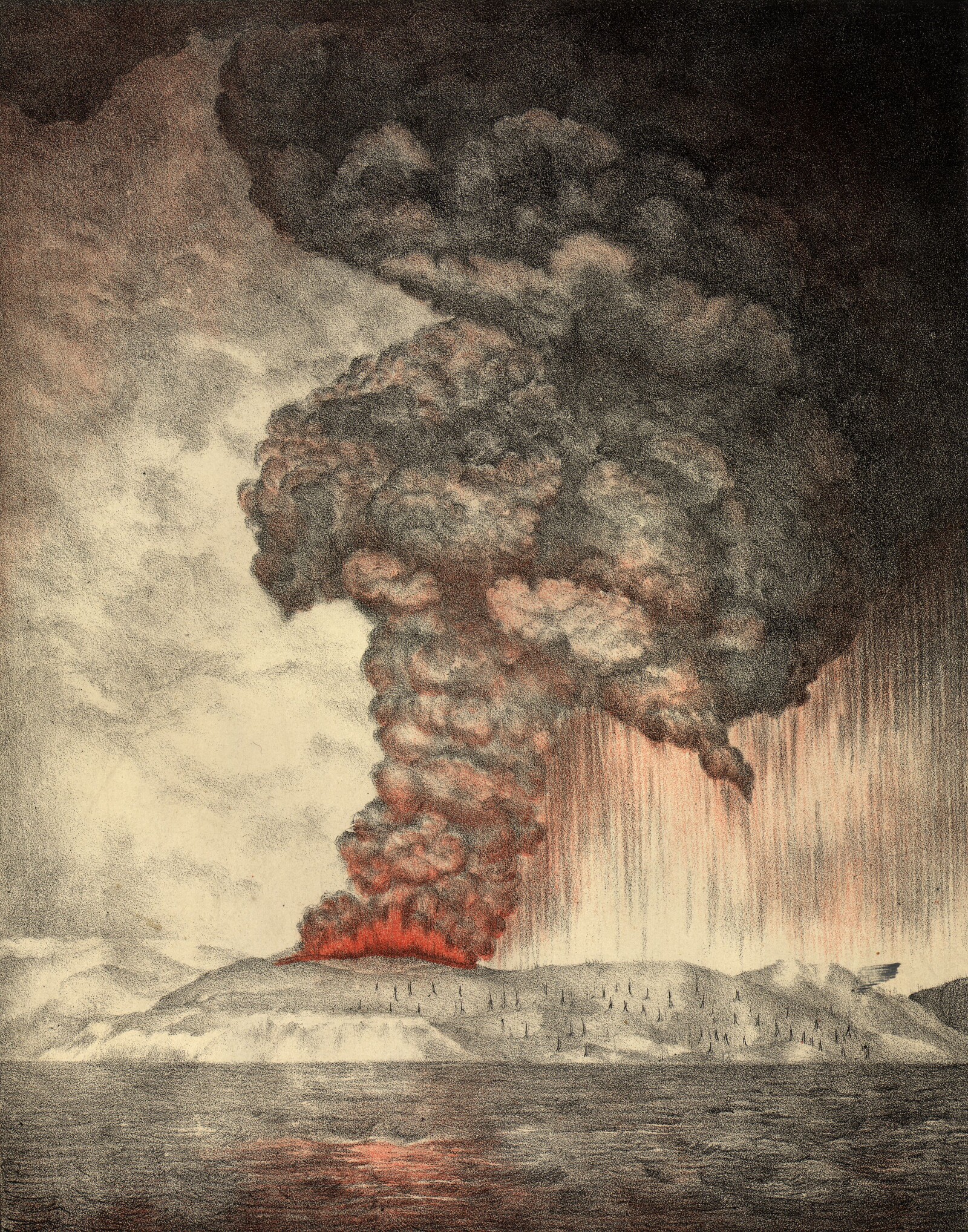

Cover of the “Experimental Issue” of The Population Bomb. Hugh Moore Fund Collection, box 6, folder 17; Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Bomb Dynamics

In 1968, Ekistics, the Athens-based magazine and brainchild of Constantinos Doxiadis released an issue on “Population Dynamics.” “The magnitude of India’s population problem is well known,” an article in the issue by George W. S. Trow began. “If New Delhi has definitely put aside any idea of compulsory sterilization, then it must reach and convince—educate, in fact—all couples who are having children. This is a formidable task…and it embraces all of India’s social problems at once.”8 Highlighting the spatial consequences of over-population, articles in the issue took a conservative stance on the “catastrophic outcomes” of large populations “encrusting the Earth’s mantle.”9

Even as the rhetoric of “Only one Earth” gripped the developed world, Doxiadis’s famous collaborator, Buckminster Fuller, had a differing, if more nuanced opinion on the ticking population bomb that had a significant impact on Indian housing policies.10 In a speech delivered at the World Resources Institute (WRI) in Carbondale, Illinois, Fuller disputed the need for any form of population control in the industrialized world, attributing higher population figures to a lowered mortality rate. “I see then that one country after another industrializes, and as they do, down go the babies and up comes life expectancy.” He continued, “I found that industrialization is the key factor to cutting down on the birth rate and much more than any other thing.”11 Articulating his belief in the reconfiguration of social practices through science, overpopulation for Fuller was a problem of non-industrial countries that could be solved through technological interventionism and the making of a world “knowledge system,” as well as a “total environment… A very complex affair.”

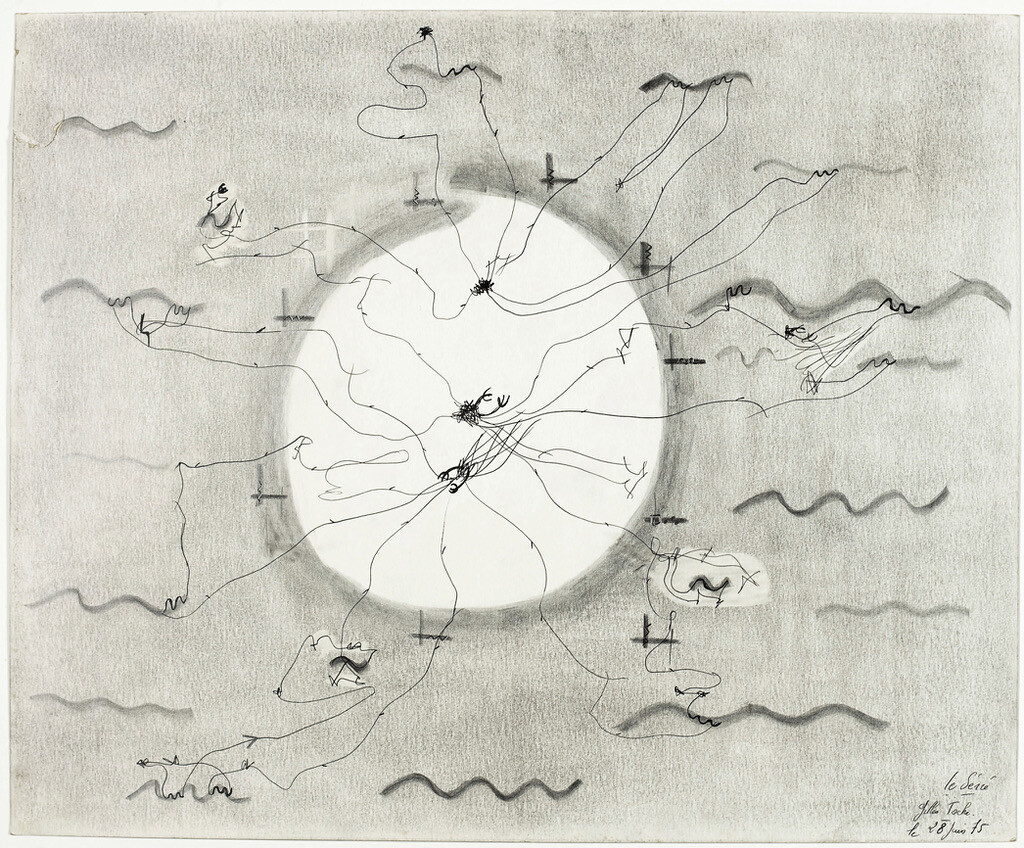

Although Fuller disputed neo-Malthusian rhetoric, his World Game—dynamic computer simulations controlled by different “players” and enacted on his Dymaxion map—saw population growth in the third world as a serious threat to the future of the planet.12 Both Fuller and his partner at the WRI, John McHale, argued that they could be “played” to explore the number of ways resources could be exploited “for the whole of humanity.”13 As Fuller argued, the World Game was an “anticipatory design science,” and were indebted to the very ideals of Leeuwenhoekian/Malthusian models of exponential growth that he rejected.14 If the World Game was a visual, if irrational calculation of the Earth’s resources, it put population statistics at the forefront of the conversation.

But Fuller’s vision for preventing resource scarcity was self-avowedly apolitical. Much like “whole earthers” like Stewart Brand, he believed in mobilizing individual capability. This openness to personal autonomy—what Michel Foucault has described as the emergent neoliberalism of the 1970s—was really a projective call for a new social order that sought to disentangle itself from the politics of governance. “It is clearly the function of politics to consolidate the scientific and industrial gains,” Fuller remarked. “Political battling for justice, as in the present struggle for the full citizens’ rights, not only for all the USA’s population, but for all the world population, is highly valid… But the right to vote alone cannot feed stomachs. Only the design science revolution can solve all the problems of clothing, housing, transporting, intercommunicating and educating all humanity.”15

Fuller also argued that autonomy began in the design of the home.16 If, as Fuller noted in the 1965 Inventory of World Resources, “the main purpose in pursing the design of environment control is to increase the ‘degrees of freedom’ which man may enjoy,” he also proposed the design of “autonomous dwellings freely deployable for single family living,” as well as the “design of larger aggregate units as fully advantaged human ecology systems at the community size level.”17 For Fuller, technologization began in the home as a way to assert individual responsibility, which was the surest way to stave off the much dreaded population explosion. Such sentiments were not ignored by the Indian Government.

Fuller’s philosophy of population that sits at the core of the World Game became a crucial component to his communications with Indira Gandhi. Addressing her as a “planetary housekeeper” for humanity, one who could govern a population through a reorganization of the home, he remarked “that a fundamental inadequacy of human life support—which [Malthus’s] statistics seemed to have uncovered—meant that all revolution must take from one side so that the other could survive. In the last two decades science has found this only-you-or-me assumption to be invalid.”18 Convincing Gandhi to transcend traditional political boundaries and “customary protocols,” Fuller argued that computers, operational research, and general systems sciences would most effectively aid in the governance of India’s large population. Indeed, his letters, which combined both admiration and advice for population regulation, underlined his belief that only through an acceptance of the inherent truth in the “technological universe” could a nation overcome population-driven resource disasters.

Environmentalism at Home

Indira Gandhi was a proponent of new environmental policies in India. Famously disputing the claims of western environmentalism at the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, Gandhi retorted, “are not poverty and need the greatest polluters?” Arguing that “the environment cannot be improved in conditions of poverty. Nor can poverty be eradicated without the use of science and technology,” Gandhi highlighted the discrepancies in the environmental ethics between the global north vis-à-vis the south, and claimed that “better planning and better action” was of primary concern for its postcolonial condition.19 For Gandhi, narrowing global power disparities could only be achieved through a nation’s self-reliance, and while recognizing that a well-implemented family planning program was necessary to “make for a healthier and more conscious population” that was more responsive to the needs of the environment, Gandhi also argued that “no method of population control can be effective without education and without a visible rise in the standard of living.”20 She continued:

The extreme forms in which questions of population or environmental pollution are posed obscure the total view of political, economic and social situations… It is an over-simplification to blame all the world’s problems on increasing population. Countries with a small fraction of the world population consume the bulk of the world’s production of minerals, fossil fuels and so on. Thus, we see that when it comes to the depletion of natural resources and environmental pollution, the increase of one inhabitant in an affluent country, at his level of living, is equivalent to an increase of many Asians, Africans or Latin Americans at their current material levels of being.21

She noted in her speech the program “Design for Living,” a joint proposal between India, Mexico, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Japan, Poland and Yugoslavia presented in 1966 at the 14th General Conference of UNESCO.22 Its newly conceived design rationale brought to the fore the importance of man’s natural habitat and saw a need not only for inculcating “new principles of civilized living,” but also the engineering of “basic materials” to promote a “design for survival.”23 Reinterpreting the concept of “standard of living,” the Program, Gandhi claimed, grasped the full implications and impact of technical advance: “It will not be easy for large societies to change their style of living. They cannot be coerced to do so, nor can governmental action suffice. People can be motivated and urged to participate in better alternatives.”24

Housing figured on Gandhi’s agenda to complete the “unfinished revolution.”25 Not uncoincidentally, Gandhi’s father—the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru—placed great emphasis on housing. At the opening of the UN Exhibition on Low-Cost Housing and Community Improvement, which took place in New Delhi in 1953, Nehru noted that, “The house is not merely a place to take shelter from the rain or the cold or the sun. It should be, an enlargement of one’s personality, and if human welfare is our objective, this is bound up with the house.”26 Indeed, under Nehru, the figure of the modern house represented social mobility, and an acceptance into the modernity of many new nation states. The question of the home was reinvigorated under Gandhi’s regime, even if it took on a more sociological view: “Any satisfaction that arises within the house affects man,” Government reports stated. “Also providing housing is a very sound preventive measure against disease and early death, social unrest, and social upheaval.”27

Family planning in the 1970s thus came to be reconsidered through the lens of the self-contained, nuclear family home. Featuring a cast of international architects and designers, low-income housing (in particular) was exemplary of the ways in which architectural discourse intertwined with class-based social engineering. If the UN Exhibition focused on the cost of materials and quick assembly of model homes, by the 1970s, house design for lower income groups focused on the merits of the small family.

Coercion: Home and Body

Beginning in 1968, the Department of Health and Family Planning lamented the lack of funding allocated to address the question of housing, and began to lobby the Planning Commission to divert its attention to the need for—and the construction of—housing for low income groups. While government documents argued, “already the vast developments by way of large increases in agricultural and industrial production have been neutralized by population growth,” it saw a need for a “manifold expansion of employment, housing, educational and other facilities.”28 Recognizing that it was precisely a lack of amenities that continued to pose significant setbacks for a modernizing nation twenty years after independence, family planning strategies in India shifted the environmental conversation from one that centered on resource scarcity to resource security.

In a nod to Fuller, the Indian family planning program took into consideration “the total man in the total environment” that was executed through an “interdisciplinary team working in co-operation with the representative institutions of the people,” or across various government departments.29 By 1969, the Department of Health and Family Planning was merged with the Department of Works, Housing and Urban Development to form the Ministry of Health, Family Planning, Works, Housing and Urban Development. Ultimately, a Working Group was set up to “ameliorate the unsatisfactory housing conditions in the country”—a process that intertwined the alleviation of poverty and the introduction of higher standards of living with the lowering of population numbers.30

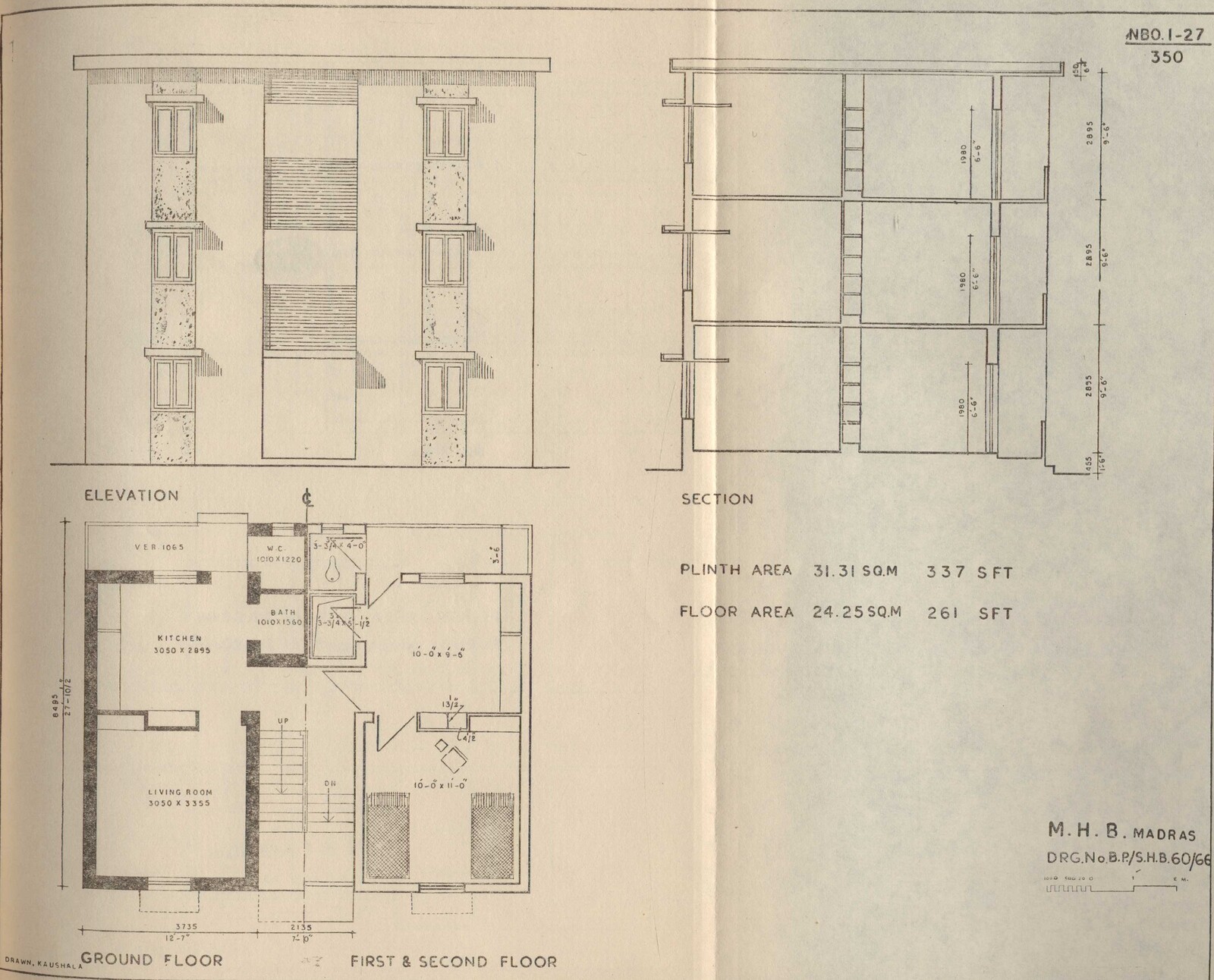

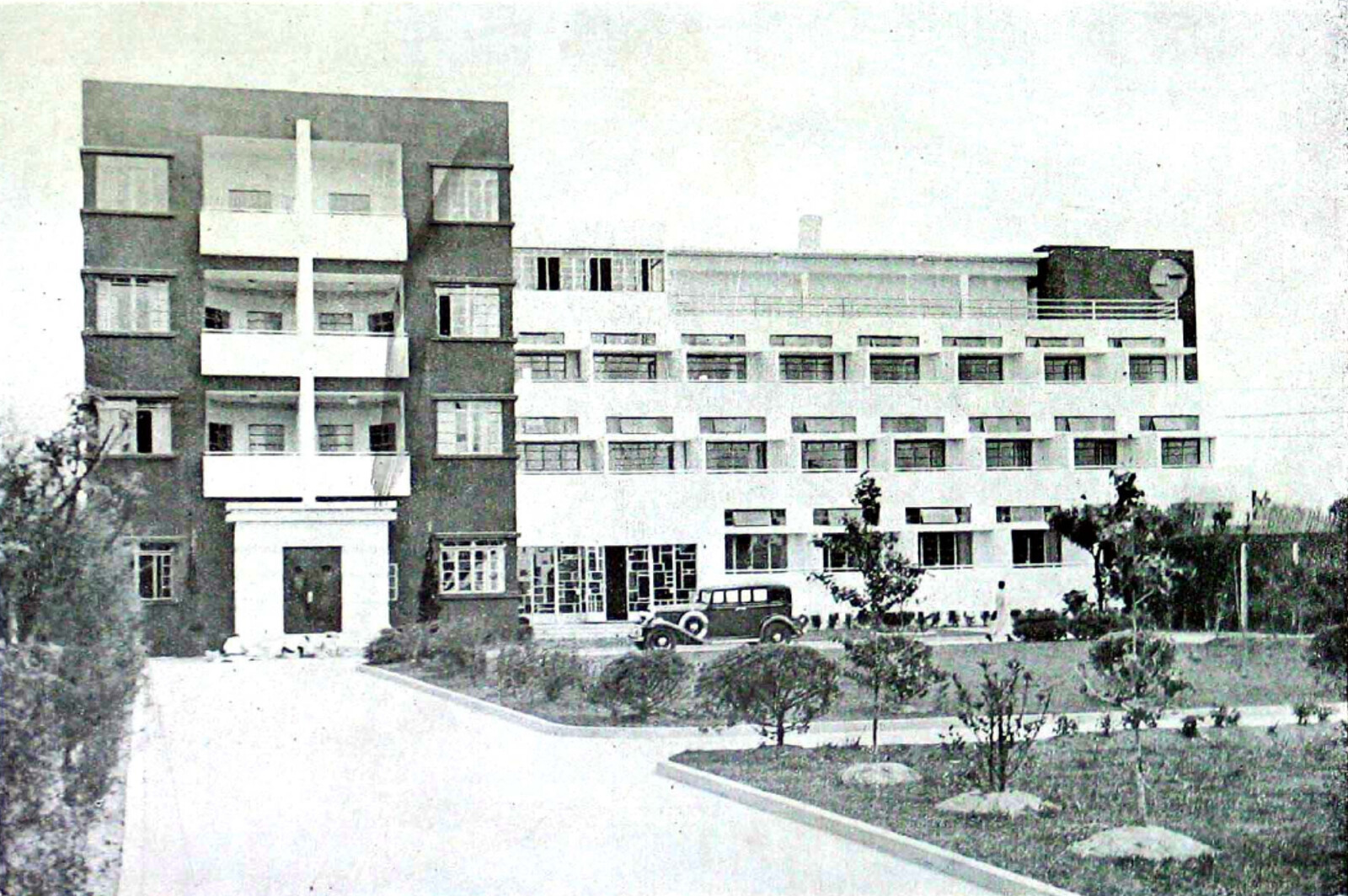

Consisting of a team that included engineers, bureaucrats, and architects (including the President of the Indian Institute of Architects, J. R. Bhalla, and well-known professionals Achyut Kanvinde and B.V. Doshi), the Working Group placed significant emphasis on the design of housing for a wide array of income groups across different regions, climates, and other “local conditions.” Their work resulted in a publication of over 500 architectural plans and sections of houses that could be implemented anywhere in the country. Considered “a good guide for the executive agencies and the public, for evolving future plans for such type of houses,” by the early 70s the National Building Organisation (NBO) in New Delhi—the center for promoting building research—selected fifty-six designs to distribute to different Housing Boards, Municipal Corporations, Improvement Trusts, Central Public Works Departments, and other state and local government authorities.31

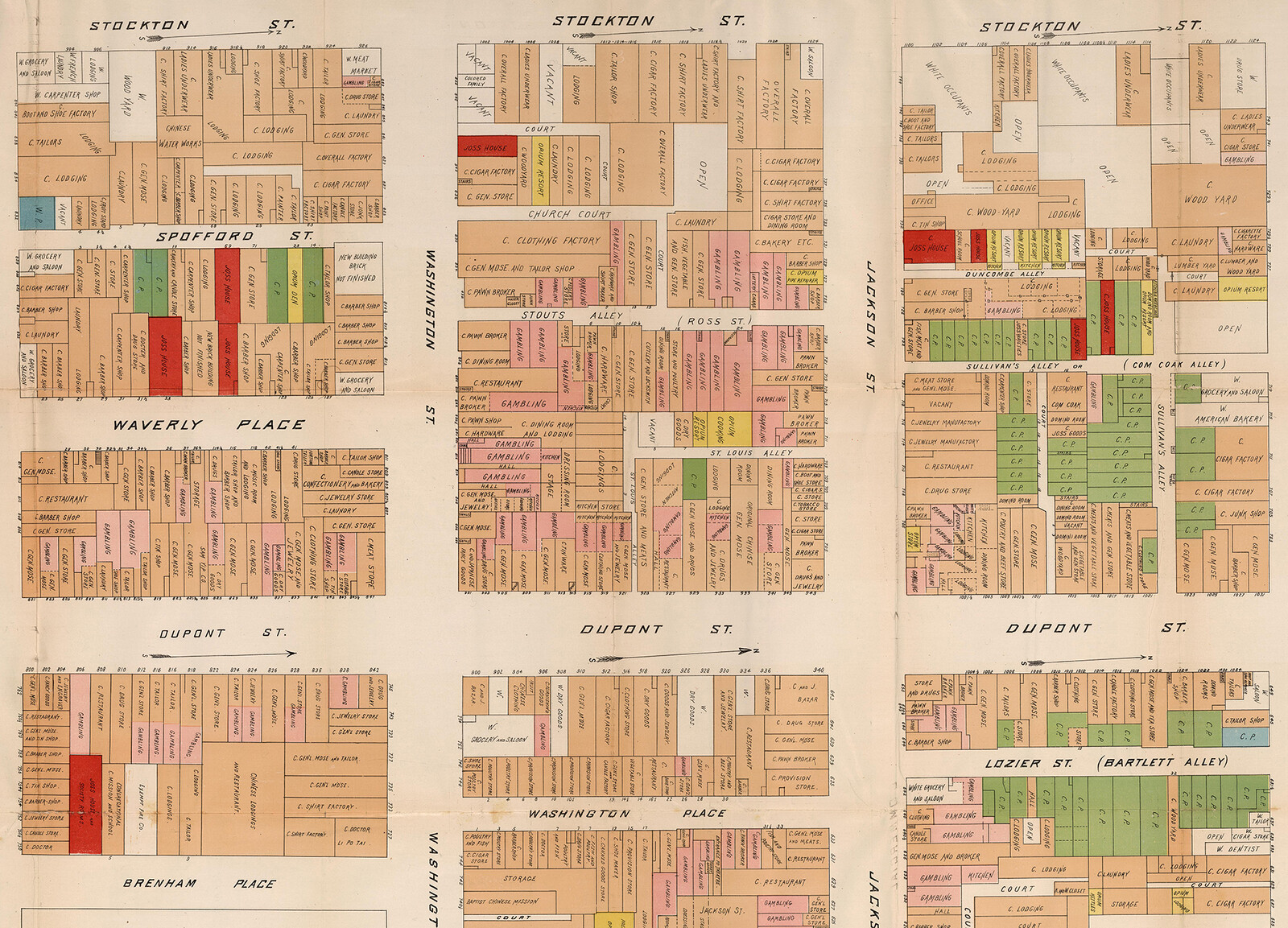

The designs were considered for four socio-economic groups. Houses with a plinth area less than 350 square feet were deemed “suitable” for slum dwellers; houses with a plinth area between 350–400 square feet were for low income groups; houses with a plinth area between 400–650 square feet for lower-middle income groups; and finally houses with a plinth area between 650–900 square feet for middle income groups. The decision to provide larger houses to certain sectors of society points to the ways in which amenity provision was bound with a conception of difference that was essential to the implementation of these schemes: middle income groups with larger houses had two bedrooms, lower income groups had one bedroom, while slum dwellers were provided with the bare minimum—houses that only included a kitchen and a multipurpose room.

While Government reports stated that the housing schemes followed the recommendations for “basic housing standards” set by the Indian Institute of Town Planners, the UN Technical Missions on Housing, the American Public Health Association, or journals such as Ekistics, their implementation on-the-ground were discriminatory along socio-economic lines. Throughout the 1970s, government reports continued to justify smaller housing for lower income groups, claiming that standards such as those determined by the American Public Health Association for “healthy” housing was “far-fetched” for a growing population.32 “It is not possible at present to meet the need-based requirement of every family. The cost of a house is disproportionately large with reference to the paying capacity of the low-income householders. Also it is not possible to provide reasonable accommodation for which these householders may be able to pay economic rent,” a 1977 report argued.33 Housing discrimination was purportedly an economic decision rather than a social one.34

Coercive tactics were soon levied by family planning and low-income housing schemes together, where forced sterilizations went hand-in-hand with the forced relocation of lower income groups into small, often substandard housing units. More significantly, the provision of housing paralleled the rise of slum clearance schemes. Not only were slums seen as the epitome of poverty, but were also regarded as spaces of moral denigration, crime, and disease. If housing was considered to be able to transform social behavior to create a “desirable sociological and physical environment necessary for the healthy growth of individuals,” slum clearance and forced relocations were imperative for the Government to achieve its goals.35 Ultimately, even as housing was promoted as an amenity for the poor, its architecture became an elaborate plan targeted at the poor.36

Housing the Emergency

In 1970s India, reproductive policies dovetailed with ideas of the healthy, single-family home. The figure of the modern home represented an acceptance into the modernity of the new nation state, while housing schemes were an opportunity to limit the growth of the poorer populations. Indeed, lower income groups became the specimens on which housing tests could be carried out, and where the control of space merged with the control of who was allowed to reproduce and grow their families. As movies such as Housing for the People demonstrate, housing and reproductive control was seen as essential to the modernization process, where families could live in dignity in their modern homes. Yet, the modern, postcolonial bureaucrat’s fantasy of a society free from crime and squalor affirmed the discriminatory, anti-poor politics of governmental discourse.

As demographers, political scientists, economists, environmental activists, and architects theorized the relationship between fertility management and the health of the Earth in the 1960s, population control unfolded across the decolonizing nations, more specifically, in its low-income regions. In India, measures to quell a global population emergency reinforced the need to target poor people who consistently had larger families, or in other words, families presenting a burden for a growing economy. Moreover, for the Indian Government, the governance of reproduction was not simply a product of medicalized discourse, but a social good to ensure the health of the nation, mirroring emergent discourses to persuade people to view procreation as a matter of social/economic mobility and personal responsibility.37

The conjunction of family planning and housing is riddled with contradictory bureaucratic plans and their on-the-ground implementations. However, the targeting of low-income groups brings into focus how architecture became essential to demonstrate the government’s good faith in the family planning program. Not only were family planning and sterilization campaigns a way to control the reproductive capacities of the poorer populations, but the home became the sphere through which government policies penetrated the everyday urban environment as well as the domestic space of the house.

I’m using a term borrowed from Marika Vicziany’s paper on family planning in India. In it, she explains Gunnar Myrdal’s definition of the “soft state” to be representative of either a democratic or authoritarian regime that lacked internal social discipline or the political desire to bring about basic reforms in the interests of the whole. She argues that India continued to be a soft state despite the imposition of emergency, and that family planning was a coercive process primarily instituted against peasants and the urban poor. See Marika Vicziany, “Coercion in a Soft State: The Family-Planning Program of India: Part I: The Myth of Voluntarism,” Pacific Affairs 55, no. 3 (Autumn 1982): 373–402.

Indira Gandhi, Selected Speeches and Writings of Indira Gandhi, Vol. III: September 1972–March 1977 (New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 1984), quoted in Asha Nadkarni, Eugenic Feminism: Reproductive Nationalism in the United States and India (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 173.

The opening lines of the film paint a somber view of the Indian nation with an acute housing shortage. “One doesn’t need a second look at an Indian city or village to spot its slums,” it begins. “Shanty towns spring up from mud and asphalt alike, with what seems to be an unnatural abandon. Grimy mohallas and tumbled-down one-room tenements, and in them, families of men packed in like sardines, sharing squalor and apathy with each other. These things make for neither dignity nor convenience. Yet, people must live somewhere, one must have a roof over one’s head, even if it has to be shared with a crowd.” See Pratap Parmar, Housing for the People (New Delhi: Films Division, Ministry of Broadcast and Information, Government of India, 1970), Film.

Gandhi, Selected Speeches and Writings.

See U. Thant, “S-0885-0001-42-00001,” in Items in Conference on Human Survival, May 25, 1970 (United Nations Archives Container S-0885-0001: Operational Files of the Secretary General U. Thant: Speeches, Messages, Statements and Addresses). Paul Ehrlich, in his 1974 paper co-authored with John Holdren, wrote: “Three dangerous misconceptions appear to be widespread among decision-makers and others with responsibilities related to population growth, environmental deterioration, and resource depletion. The first is that the absolute size and rate of growth of the human population has little or no relationship to the rapidly escalating ecological problems facing mankind.” The second misconception he noted was that environmental deterioration consisted primarily of pollution, while the third was that natural resources were in an unlimited supply. Of course, in the context of the cold war, anxiety around resource conservation was ideologically encoded, and the distribution of energy linked to adjudicating the alliances between the US and the Soviet Union. See John P. Holdren and Paul R. Ehrlich, “Human Population and the Global Environment: Population Growth, Rising per Capita Material Consumption, and Disruptive Technologies Have Made Civilization a Global Ecological Force,” American Scientist 62, no. 3 (May–June 1974): 282–292.

As Matthew Connelly notes, no other country attempted to control its fertility over such a long period. India was the first country to adopt policies to reduce rather than improve fertility, and together with other South Asian countries, was the testing ground for new contraceptive techniques. See: Matthew Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Holdren and Ehrlich, “Human Population and the Global Environment,” 282.

George W.S. Trow, “India’s Haphazard Birth Control Program,” Ekistics 25, no. 149 (April 1968): 232–233.

For instance, Roy Greep, a professor of Population Studies at Harvard, wrote in his article to the issue: “the reason for the present unprecedented increase in population growth is the introduction of death control without birth control.” Noting that the population growth in advanced countries was modest in comparison to the “less-developed and heavily populated nations,” Greep outlined the foremost apprehensions of the time: resource scarcity, balance of political power, and the “rising tide of colour.” If his article mirrored a racialized, elitist anxiety where the poorest and weakest would outnumber the most capable, it also framed much of Euro-American environmentalist discourse at the time, which claimed that unchecked population growth (from the former colonies) threatened the welfare of mankind. “The one and only humane solution to the population problem,” Greep argued, “is birth control, whether practiced with contraceptive aids or by voluntary restraint.” See Roy O. Greep, “The Population Crisis is Here,” Ekistics 25, no.149 (April 1968): 208–210.

See Barbara Ward and René Dubos, Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a Small Planet (New York: W.W. Norton Company, 1972).

“Population Control Dynamism of Universe” (Typescript of Buckminster Fuller’s talk to Carbondale Staff Meeting), November 1969, M1090_S8_B75_f8, Mixed Materials 75, Folder 8, Buckminster Fuller Papers, Stanford University.

For more on Buckminster Fuller and the World Game, see Mark Wigley, Buckminster Fuller Inc. (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016).

Indeed, in the early 1960s, Fuller and his collaborator, John McHale, had recognized that there were negative aspects to resource over-exploitation. Citing figures and estimates from scientific journals and magazines, UN reports, and US Congressional proceedings, they noted that, “so far, our modification of the earth has proceeded with little regard for the intricacy of the overall ecological balances which maintain life on earth. We have taken little heed, for example, in modifying the environment for our own use, of the disruption of the populations of animals, micro-organisms, plants, etc., with which the maintenance of our own ecological cycle is still closely interwoven.” See John McHale, “World Design Science Decade Phase 1 Document 4” (World Resources Inventory, Southern Illinois University, 1965), 22.

The relationship between resources, sustenance, and the number of people—a theory supported by mathematical models where people reproduce at a geometrical rate, but the resources to support them could only grow arithmetically.

Buckminster Fuller, “World Design Science Decade Phase 1 Document 3” (World Resources Inventory, Southern Illinois University, 1965), 109.

Ibid. Fuller writes: “Politicians are rarely scientific minded and being preoccupied with this and next year’s elections, do not think about and would not dare to initiate long years of comprehensive readjustment threatening to the special economic advantage of those who pay for their campaigns. Because of the scientific discovery of fundamental and total life support adequacy and feasibility politics are obsolete; they are omni-lethal to humanity’s survival. You are apolitic, that is why you are essential to humanity at this critical moment in all human times. You are a clear-headed planetary housekeeper for humanity. When the housekeeper knows that there is enough for all, she doesn’t need any politicians around the house.”

McHale, “World Design Science Decade,” 90.

Correspondence from Buckminster Fuller to Indira Gandhi, January 1970, M1090_S2_B195_f9, Mixed Materials 76, Folder 10, Buckminster Fuller Papers, Stanford University.

“Human Environment: Address to the Plenary Session of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment at Stockholm, June 14, 1972,” Indira Gandhi Speeches and Writings (New York: Harper Row, 1975), 193.

Ibid., 193.

Ibid., 195.

Design for Living was a joint proposal between India, Mexico, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Japan, Poland and Yugoslavia presented at the 14th General Conference of the UNESCO, that brought to the fore the importance of man’s natural habitat.

“A Design for Living: A project for UNESCO action sponsored by consensus at the Nehru Round Table, New Delhi, September, 1966,” in MARG 20, no. 3 (June 1967): 5.

“Human Environment: Address to the Plenary Session,” 199.

Ibid., 198.

Jawaharlal Nehru, “Opening Remarks at the International Exhibition on Low-Cost Housing by the Prime Minister, 25th October 1953,” New Delhi.

“Government Aided Housing Schemes,” Report of the Development Group on Low Cost Housing (New Delhi: Ministry of Works and Housing, National Buildings Organisation and U.N. Regional Housing Centre ESCAP, September 1977), 10.

India: Family Planning Programme since 1965 (New Delhi: Ministry of Health, Family Planning and Urban Development, Department of Family Planning, 1968), 1.

Ibid., 7.

See Annual Report 1968-1969 (New Delhi: Ministry of Health, Family Planning, Works, Housing and Urban Development, 1969), 31; Report of the Development Group on Low Cost Housing, 1.

A Collection of Designs of Houses for Low Income Groups (New Delhi: Government of India National Buildings Organisation and UN Regional Housing Centre ECAFE, 1969), iii.

Report of the Development Group on Low Cost Housing, 8.

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., 9. “Analysing our goal with regards to housing, it should be aimed at initially providing a dwelling with a minimum accommodation of one living room, one multipurpose room with cooking space, a bath and WC, but with the objective of having later on a minimum house consisting of two living rooms, a kitchen, a bath and a WC.”

Ibid., 8.

Gyan Prakash, Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 281.

Savina Balasubramanian, “Motivating Men: Social Science and the Regulation of Men’s Reproduction in Postwar India,” Gender and Society 32, no. 1 (February 2018): 34–58, 37.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.