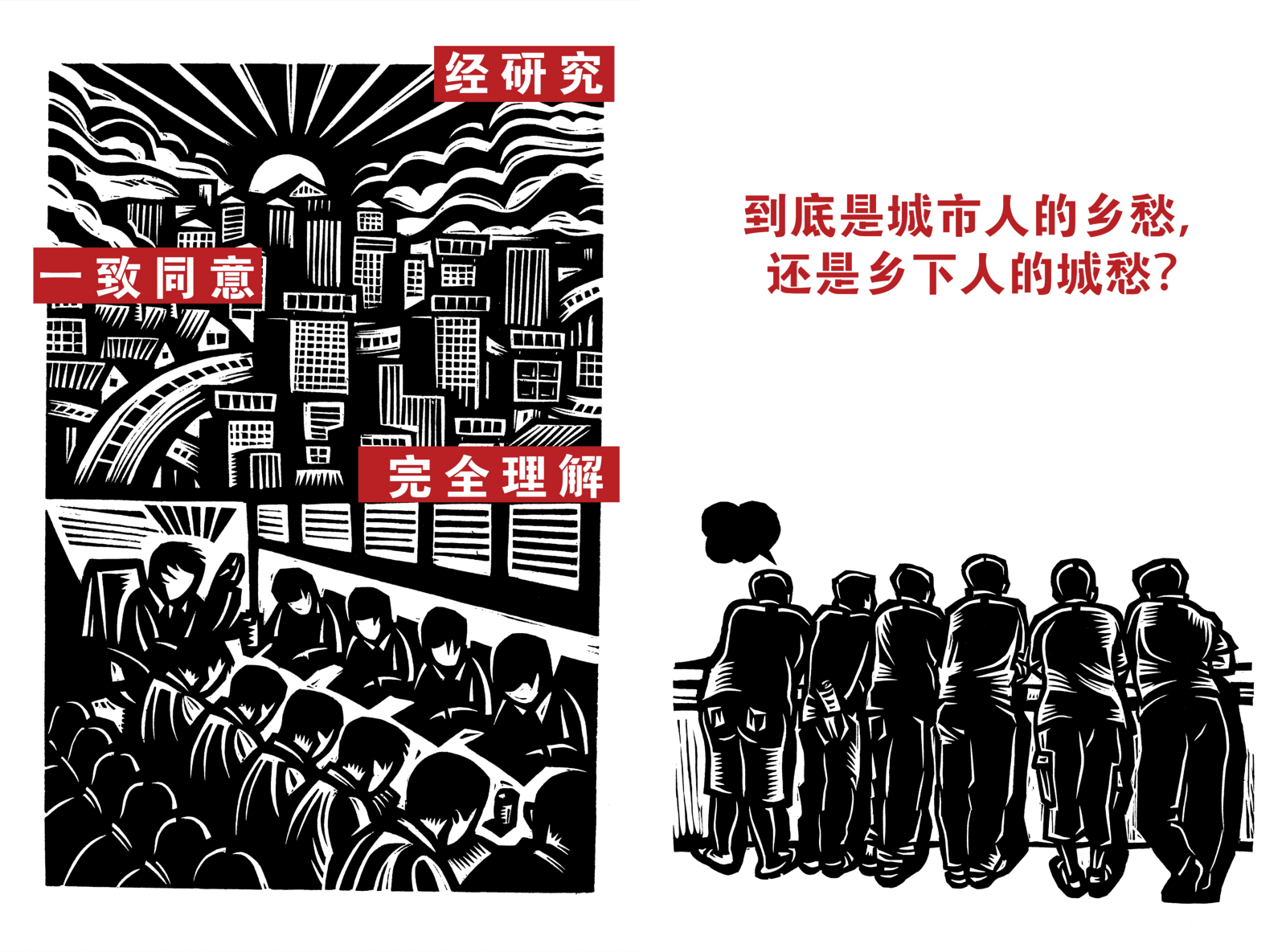

The frontier is a space where actors from different worlds have an encounter for which there are no established rules of engagement. Whereas the “historic” frontier was at the edges of empire, today’s frontier is deep inside large, complex, and mixed global cities.

These cities, whether in the Global North or South, have become strategic for the functioning of corporate capital. But they have also become strategic for the disadvantaged, outsiders, discriminated minorities, and those who lack power more widely. The disadvantaged and excluded can gain presence in such cities, presence vis-à-vis power and, even more important, vis-à-vis each other. This mix of conditions signals the possibility of a new type of politics, centered around new types of political actors and spaces. It is no longer simply a matter of having power or not. There are new hybrid bases from which to act; spaces where the powerless can make history, even without becoming empowered.

Making the Political

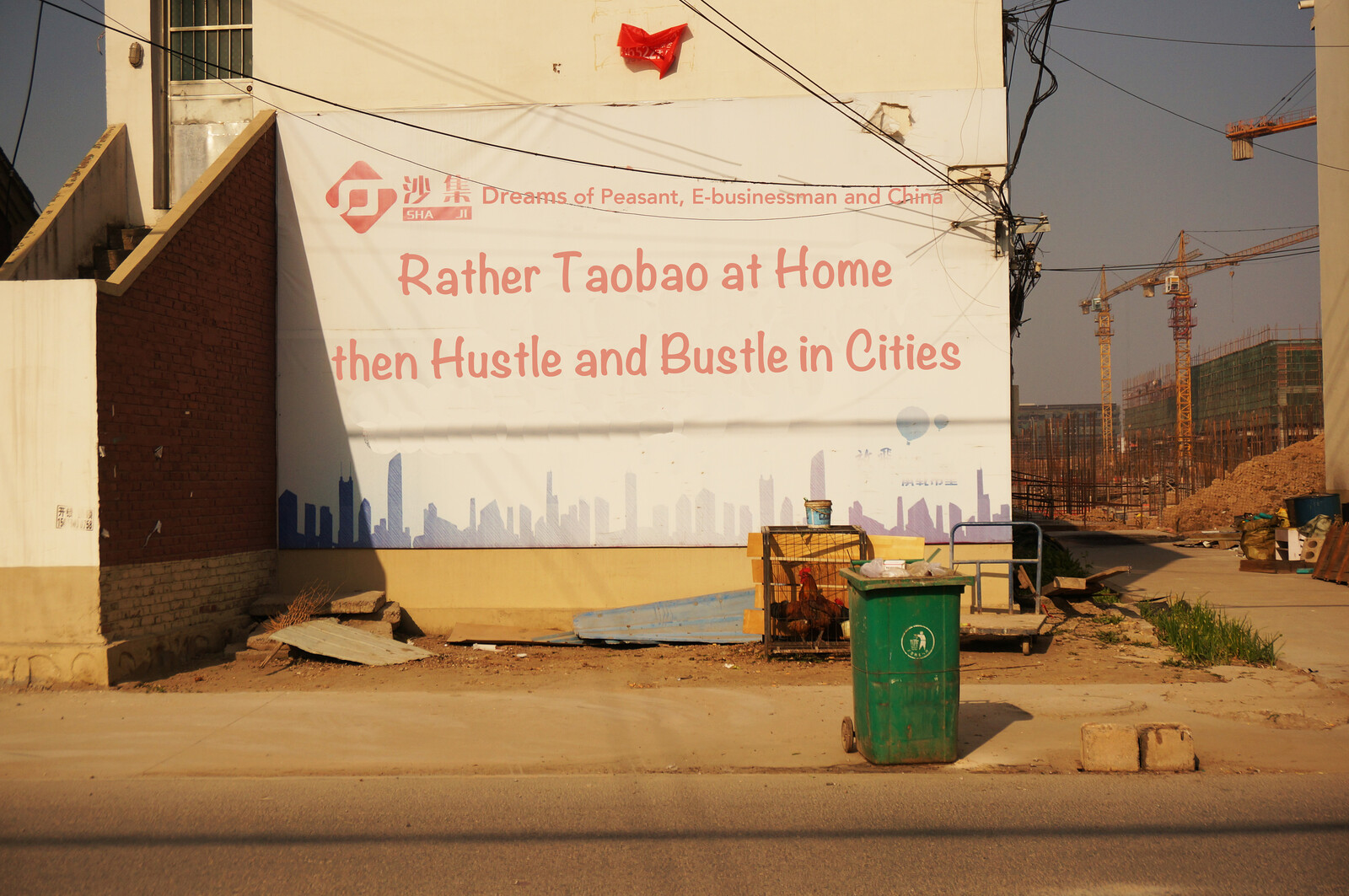

In city after city, informal politics are being made by actors-with-a-project, regardless of whether they themselves are powerful or not. It is particularly the work of making—the public, the political, the imagined—that is critical today, a time when the political space of the nation is becoming increasingly dominated by powerful and unaccountable actors, both private and public.1

The city, unlike office “parks,” for example, enables a kind of public-making work that can produce disruptions. They can render the local and silenced legible. Today’s global cities are one key space for this making. They are one of the few frontier spaces in a world where so much has already been bought up. With all their inequities and conflicts, it is in cities where those without power get to make a history, a local economy, and a culture.

It is the possibility of making that matters here, and we should not squash it. The multiplication of bordered spaces, dividing those whose advantage grows from those who lose ground, is not good for a city. Mixing a city’s differences is far more compelling, enabling, and also often more just—if we think of a vast diverse city that no actor can fully control.

New Borderings

Thinking of the large complex city as an emergent frontier space—that is, a space where multiple differences come together—becomes a tool in the context of increasingly hardwired borderings, of which gated communities are but the most visible manifestation. The use that corporate capital makes of “our” cities is part of that hard bordering, but in a much more consequential way than the more familiar gated communities.

The common assertion that we live in a far less bordered world than thirty years ago only holds if we consider the traditional borders of the interstate system, and then only for the cross-border flow of capital, information, and particular population groups. In short, it is an extremely limited and partial openness.2

While some barriers for some sectors of our economies and society have indeed been lifted, enabling them to cut across interstate borders, we are far from moving towards a borderless world. For these same sectors are actively making new types of borderings by engaging only certain parts of countries and cities to generate their own “open” cross-border geographies.

These are not old imperial modes where conquerors wanted it all. Today’s financial conquerors want specialized, and selective geographies: they need specific sites within national geographies.3 They do not want to deal with a whole country. They want instruments that allow them to cut across international borders and occupy only the sites of that territory that they need or desire for their own projects—differing radically from the older imperial land grabs.4

In short, the key in a growing number of today’s emergent global urban political situations is not the elimination of more and more inter-state borders. It is rather that powerful actors have made a cross-border space—partly material and partly digital—that cuts across older barriers and occupies only specific areas of each of the countries where it operates.5

A simple illustration of this is the chain of global financial centers that can now be found in all countries that matter to high-finance. Each of these financial centers is a massive material event that installs itself in a city that provides all the key inputs: land, buildings, digital connectivity, and the mix of highly specialized knowledges that go with it all. But unlike old imperial modes, these financial centers have zero interest in conquering a whole country—they only want what they need.

From global finance to mining, construction, and beyond, these are today’s transversal, partial, and quite impenetrable cross-border geographies of power. It is in such a context that the global city, where live both the powerful and the poor—becomes a frontier space with political consequence and opportunity.

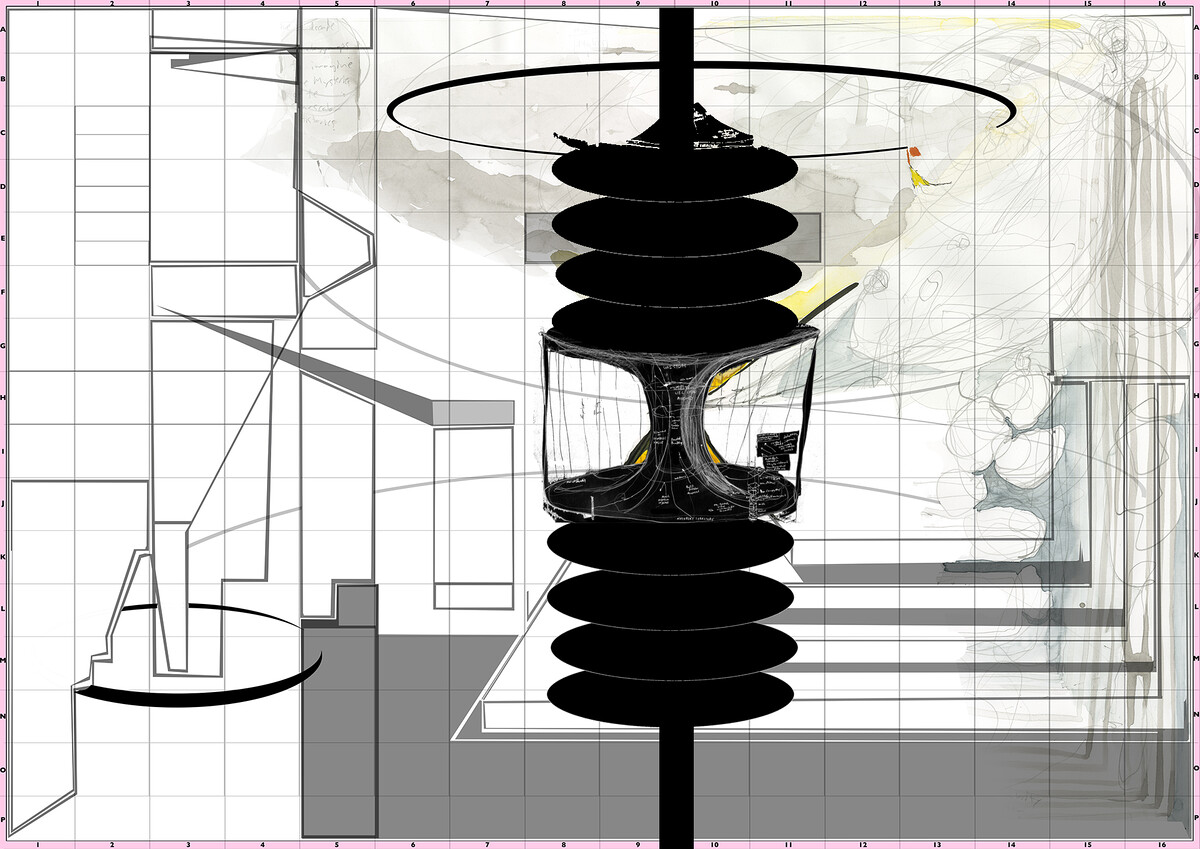

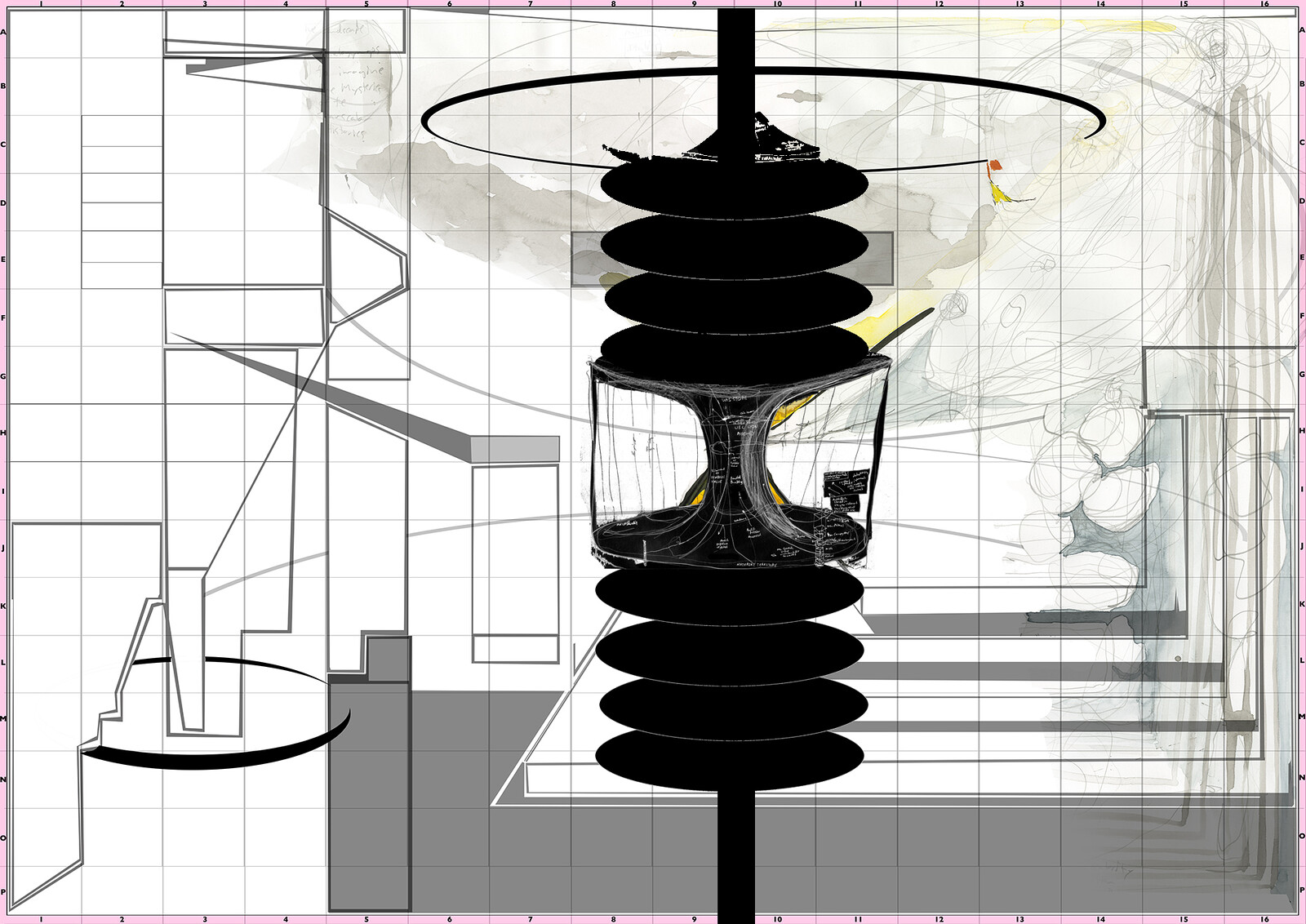

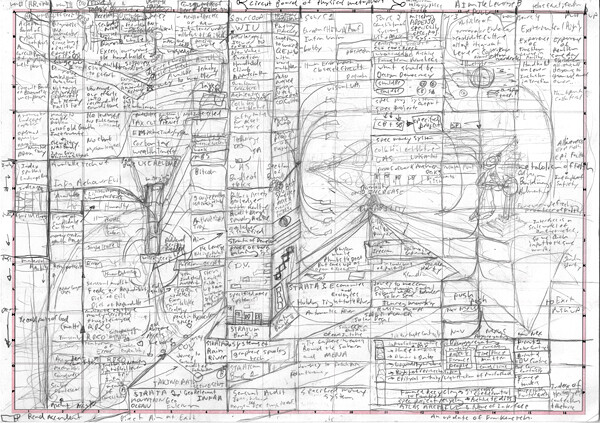

Hilary Koob-Sassen, gridwork 1B, 2017.

The Global Street: Indeterminacy is Critical

The street needs to be differentiated from the classic European notion of public space as a ritualized site for public activity, such as the piazza and boulevard. The street, which also includes unmarked squares and any available open space, is a raw, unpredictable space. The street can thus also be conceived of as a space where new forms of the social and the political can be made, rather than a space for enacting routines as might be the case with a grand traditional park such as the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. With some conceptual flexibility, we might say that, politically, the street and square are marked by action, whereas the boulevard and piazza are marked by rituals.

Electronic interactive domains should be considered part of these larger ecologies for making, rather than as a purely technical domain. If we make conceptual and empirical room for the broad range of social logics that drive its users, we can detect diverse cultures of use in the ways these technologies get deployed. Each logic and culture of use activates an ecology of meanings and associated actions. One project with great potential is, for instance, what we could call “open-sourcing” the neighborhood.6 Seen in this way, social media can become an effective third force in tactical urbanism.7

Towards a Tactical Urbanism?

Against the background of the nation-states partial disassembly, large and complex cities emerge as strategic sites for making new orders—spatial, economic, political, environmental, cultural, and contestatory. Tactical urbanism can find strong ground for executing a vast range of projects that the disadvantaged and their poor or modest neighborhoods need to have a better life, to fight for their rights, and more.8

We need to relinquish our attachment to a certain kind of European urbanity—with all its positive enablements. In most of today’s world, it is the large, somewhat overwhelmed city that represents the future. While most cities in the world are and will remain medium sized and be reasonable places, it is in large cities, in both the Global North and the Global South, that more complex futures are emergent.

The last two decades have seen an increasingly urban articulation of global logics and struggles and an escalation of the use of urban space for making political and economic claims by a very broad range of actors with very diverse agendas—some just and some dubious. These claims come from citizens, from the rich and the poor, from national and foreign investors, from gentrifiers, from social housing activists, and more. Unlike what is often the case with national initiatives, the materiality of urban space makes much of this visible.

It is in global cities that today’s increasingly private and elusive forms of capital hit the ground and become concrete and visible. The current condition in global cities is creating not only new structurations of power, but also operational and rhetorical openings for new types of actors and their projects. That globalization’s strategic components are localized in these cities means that the disadvantaged can at least engage with moments in the trajectory of today’s global economy and power. Tactical urbanism can find diverse spaces in such cities, spaces that might have been previously submerged, invisible, or without voice.

The localization of the most powerful global actors in these cities creates a set of objective conditions for engagement, whether those involved want it or not. Examples of this include the by-now familiar struggles against gentrification as it encroaches on minority and disadvantaged neighborhoods. Virtually all major cities—from New York and London to Mumbai and Shanghai—have examples of the expulsion of low-income households and modest commerce from low-income neighborhoods that are then transformed into high-priced residential and business zones. While many of those anti-gentrification struggles fail, they have left a significant trace. Today, just about every urban dweller and local politician in major cities is aware of these struggles. They have become a datum—a fact that is in the public domain.

The emergent struggles for urban space in a growing number of cities across the world also tells us something that I have elsewhere referred to as the capacity of the city to talk back.9 Such cities are spaces where the growing numbers and diversity of the disadvantaged can take on a distinctive “presence,” and in that sense, possibly constitute a political infrastructure for a tactical urbanism.

This all points to the importance of making a distinction between powerlessness and invisibility/impotence. The disadvantaged in global cities may lack power, but they can gain “presence” in their engagement with power—and, importantly, also gain presence vis-à-vis each other and thereby know that they are many. And while the literature on empowerment tends to reason that only empowerment counts, I would argue that gaining complexity in one’s powerlessness, even if one does not become empowered, can still make a difference. This type of complexity in the condition of powerlessness can, and increasingly is, becoming political “speech.” One effect is a world-wide recognition that it is happening in major cities across the world, and that there is justice in this battle. In all these ways, a history of transversal recurrences is being made. We now know, and we will not forget.

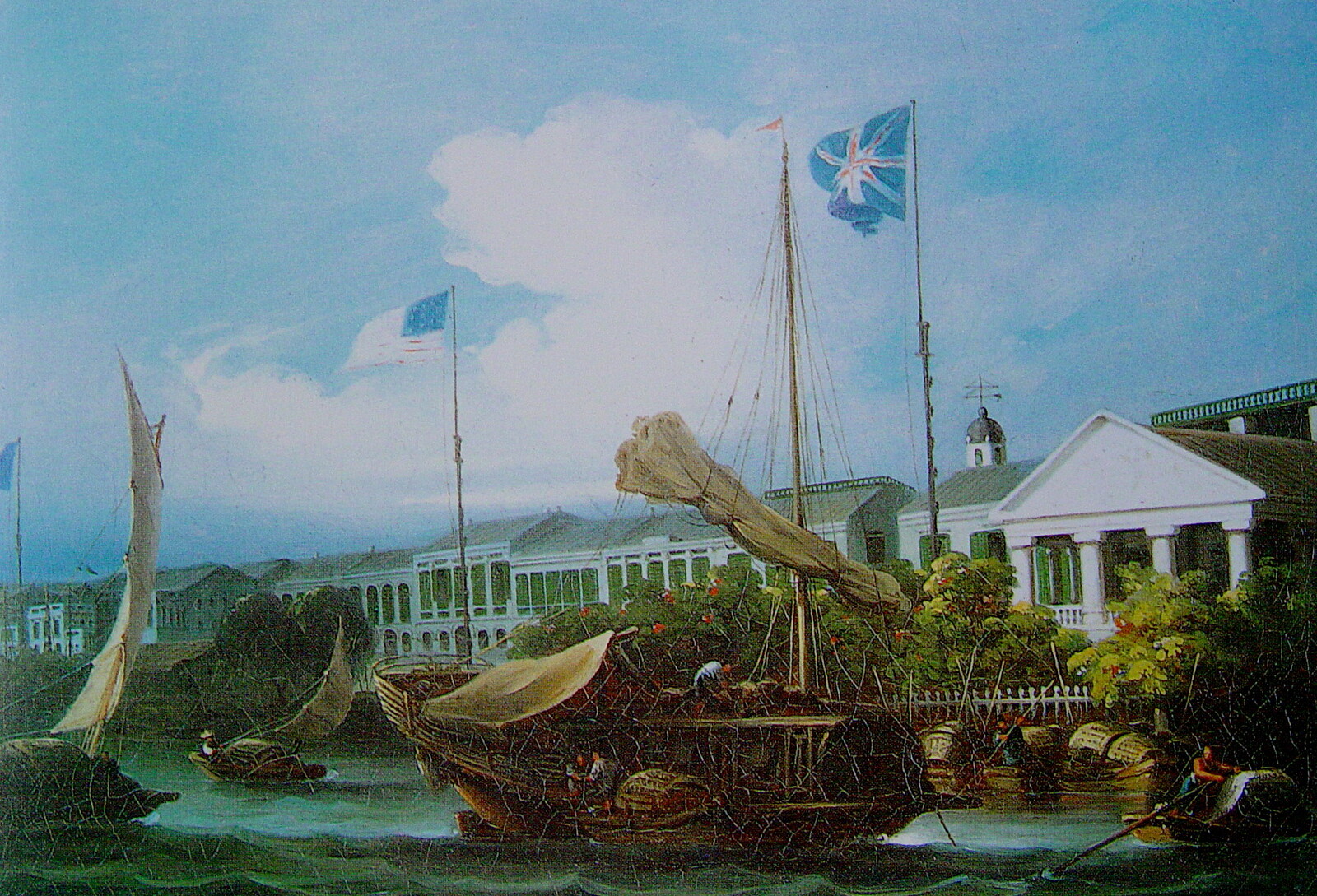

Yet only certain spaces enable this today. While in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, mines and plantations in the Caribbean, for instance, were key spaces for political organization, today’s plantation and mine workers are in a situation of flat powerlessness, where there is no possibility to make history or politics.10

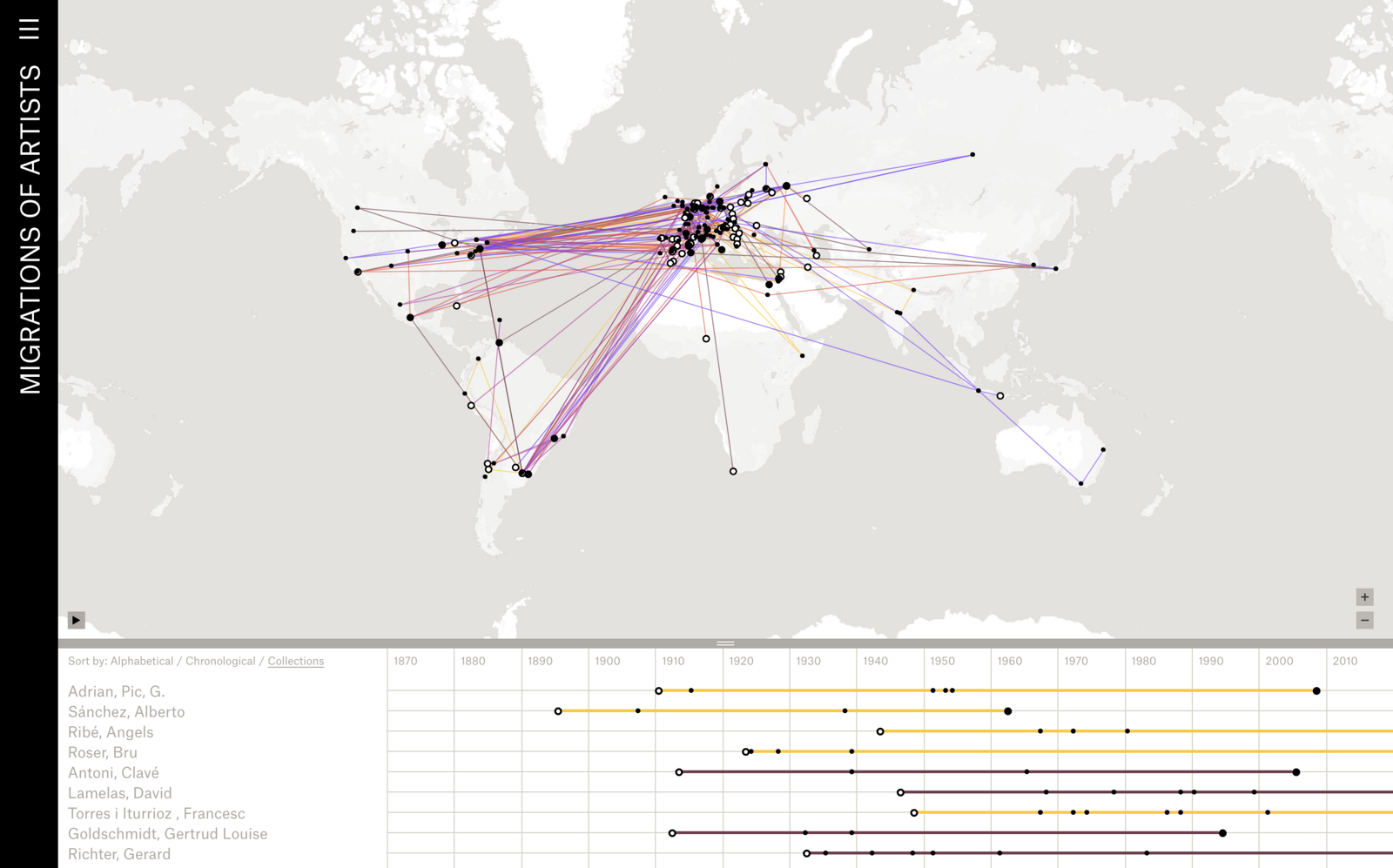

I have long argued that in today’s world, it is cities that offer the powerless the possibility of making presence. Further, while many of today’s urban struggles are highly localized, they represent a form of global engagement.11 Their globality is constituted as a horizontal, multi-sited recurrence of similar struggles in hundreds of cities worldwide. And though the larger project often cannot be achieved, there is an accumulation of efforts that brings knowledge and transversal recognition among the powerless.

Such struggles point to the making of operational and rhetorical openings for new types of political actors, including the disadvantaged and those who were once invisible or without voice. Tactical urbanism, understood in this way, engaged in multiple specific sites in specific cities, can become a global space for recognizing each other and for making.

See, for instance, in major cities, the aggressive buying of property, often left unused. Saskia Sassen, “Who owns our cities – and why this urban takeover should concern us all,” The Guardian Cities (November 24, 2015), ➝; and Saskia Sassen and Hilary Koob-Sassen, “A monster crawls into the city’ – an urban fairytale by Saskia Sassen,” The Guardian Cities (December 23, 2015), ➝.

Berrin Chatzi Chousein, “‘Digital Tools Narrow The Space Of The Divide Between Oppressors And Oppressed’ Says Saskia Sassen,” World Architecture Community (July 14, 2016), ➝.

See Saskia Sassen, “The Global City: Enabling Economic Intermediation and Bearing Its Costs,” City & Community 15, 2 (June 2016), 97–108.

Saskia Sassen, “Embedded Borderings: making new geographies of centrality,” Territory, Politics, Governance (March 6, 2017), ➝.

For an extensive set of data about major global cities, see LSE Cities’ “The Urban Age” project: ➝.

A city’s ‘backtalk’ is one element of open-source urbanism: myriad interventions and little changes from the ground up contribute to making a city. Multiple, small, inconspicuous interventions together are evidence of a city’s constant evolution. See Saskia Sassen, “Open-Sourcing the Neighborhood,” Forbes (November 10, 2013), ➝.

See, for example, the Solar Canopy project, ➝. For a range of digital innovations specifically geared towards the needs of low-income neighborhoods and the challenges they face at home and at workplaces, see Saskia Sassen, “Digitization And Work: Potentials and Challenges in Low-Wage Labor Markets,” Open Society Foundation (2015), ➝.

Lindsay Mackie, “How to Exclude and Expel Most of the World – Call it Growth,” New Weather Institute (March 5, 2016), ➝.

Saskia Sassen, “Does the City Have Speech?,” Public Culture 25, 2: 209–21, ➝.

Saskia Sassen, “Predatory Formations Dressed in Wall Street Suits and Algorithmic Math,” Science, Technology & Society 22:1 (2017): 6–20.

Saskia Sassen and Hans Haacke, “Imminent Domain: Spaces of Occupation,” Art Forum (January 2012), ➝.

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”

Category

Subject

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”