Two months after the Jamia Millia incident, in February 2020, the Jamia Coordination Committee, a student organization, released CCTV footage from that night. It shows armed paramilitary and police agents entering the Old Reading Hall dressed in camouflage combat gear, faces covered in scarves. They lean over desks and beat students working at computers or huddled over stacks of paper. Despite the narrative the state has maintained, the video proved, without a flicker of doubt, the sadism inflicted on students. “I’ll end my message with this one appeal,” says Umar Khalid in the dispatch he recorded before his arrest. “Do not get scared.”

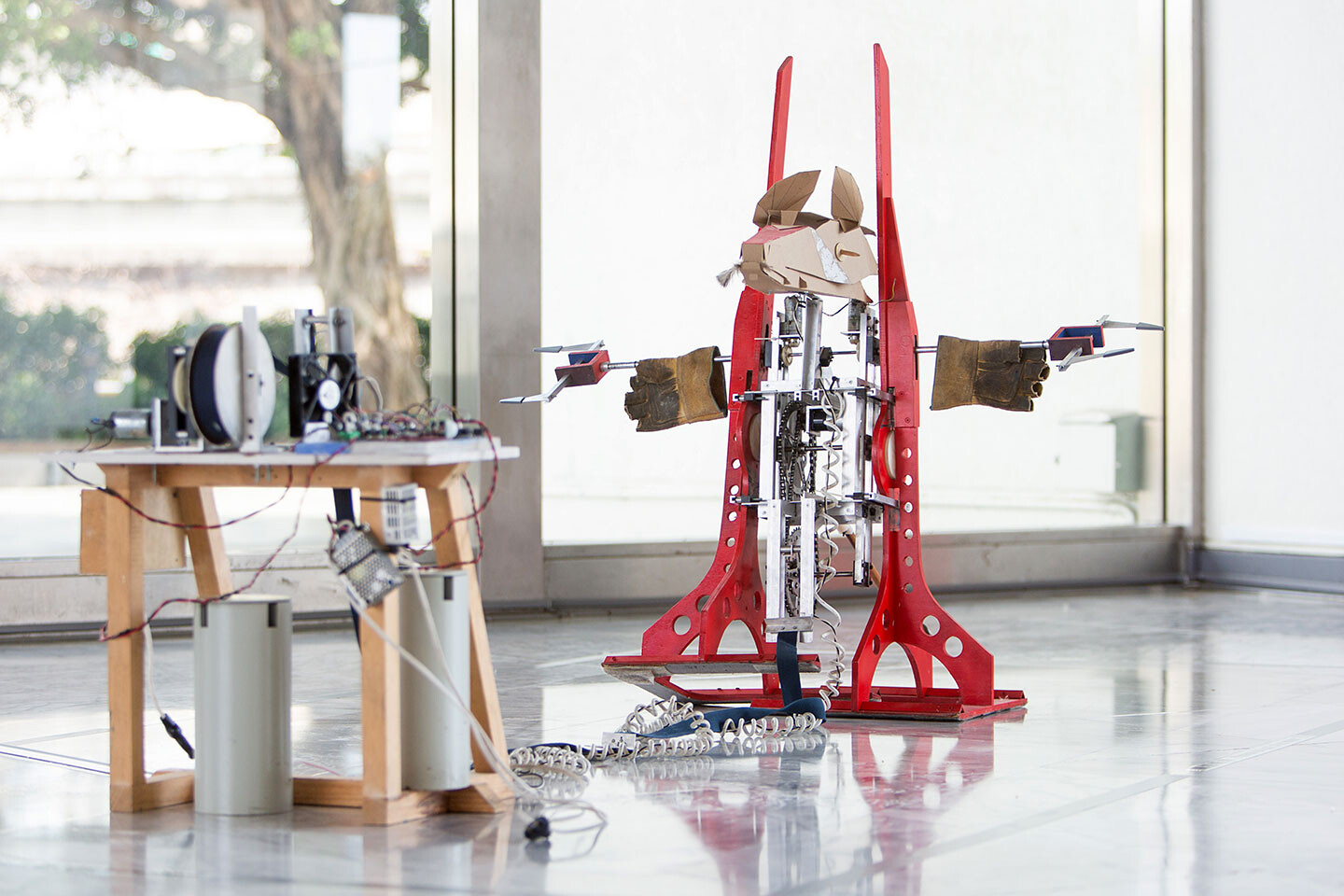

The techno-social is the form of the social that comes after its end. It is neither a virtual nor a global digital community, but a component of the milieu generated by a new technical being—the digital computational network. It was triggered not so much by social media, as first assumed, but by the turn whereby social computing no longer simply supported social interaction but started “to process the content generated by social interaction,” making its results “usable not just by users but by the digital systems that supported their activities” (Thomas Erickson).

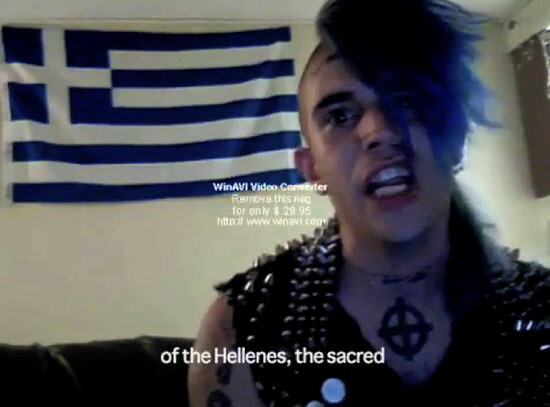

How do the images (and words) that we create go beyond the spaces in which they came into existence? How can stories cross over from their own bubbles to the other side of a highly polarized world? How can they live, sustain, and even contaminate opposing ideologies—like ink slowly dripping into a glass of water until it turns blue? After all, isn’t this exactly how propaganda has been diffused among the masses by various governments of the past, especially dictatorial ones—in little shifts and triggers and not in explosive events? The parameters of what was considered normal would be quietly stretched out, without us even realizing it. Today these shifts of normalization are seeded in viral images. I am convinced that the photographer today is out of touch with the complete image world.

Is there a need for a Roma museum of contemporary art? Who would shape its collections, and according to what criteria? Is it possible to avoid the traps of stereotypical representation? How would such a collection represent the civil rights and emancipatory struggles of the Roma people, along with the historical and present-day contexts of these efforts?

The singular image of the blue marble is now divided into different worlds which form a constellation that has nothing to do with celestial harmony. We are caught within it, where for each decision we must make, the gravitational attractions of the different configurations of earth make one’s head rotate as if on a merry-go-round. The model for describing this condition is not just some new form of dialectic (implying only two poles), but rather a configuration with a multiplicity of polarities.