November 12, 2023–June 16, 2024

Trying to find a critical entry point into—or exit from—Paul Pfeiffer’s retrospective is not unlike the challenge of navigating its labyrinthine layout of walls, ramps, and rooms within rooms. An architecture designed by the artist with Hollywood sound stages in mind slowly unveils a spectacle of spectacles, showcasing over thirty works spanning the past twenty-five years and dizzying ranges of scale, duration, material, and method. Pfeiffer is best known for his bite-sized video works, which sit here alongside extra-large installations, miniature dioramas, full-scale sculptures, room-wide projections, and expansive photo series. Video durations range from four seconds to ninety days. Most of his moving-image works have no sound, but the space hums with the distant, ambient clamor of a crowd. Michael Jackson’s voice has been replaced by that of a Filipino choir. The Stanley Cup levitates in mid-air. Marilyn Monroe and Muhammad Ali have been scrubbed out of their respective beaches and boxing ring. Raucous activity and haunting absence somehow go hand-in-hand.

If there’s a true North to Pfeiffer’s practice, it might be mass media’s protean relationship to consumer technology, how the latter shapes the former and vice versa. It’s a marvel to witness the artist’s use and abuse of both, keeping pace with the sprinting evolution of personal devices from the late nineties to today. In the museum’s low-ceilinged “reading room,” a flatscreen monitor mounted to the back wall loops two brief Art21 video profiles, from 2003 and 2023 respectively. For about five seconds, the older spot shows the artist in his late thirties, seated at a simple wood desk, surrounded by computers. At front and center is an Apple Power Mac G4, that pinnacle of Y2K-futurist design; its bulky, clear-plastic monitor and tower are flanked by an even more corpulent iMac G3 and a black PowerBook G3, marketed as the fastest laptop of the third millennium. These were the machines that convinced consumers not only that computers could be cool, but that Macs were tools for creative work. Pfeiffer had cut his teeth on this new technological relation during a day job at a New York advertising agency (as Niklas Maak tells it, Pfeiffer got canned for “making scans for friends at night from the hip-hop magazine XXL”).1

Here is the fulcrum on which Pfeiffer’s practice teeters, and from which it extracts maximum delight. He transformed video art during analogue television’s last gasp—most countries transitioned to digital broadcasts by the late 2000s—and the early works hang perfectly in that balance: he transmuted TV into pixels, but still anchored his output in objecthood. Among the videos on view in “Prologue…,” it’s rare to see a screen or projector treated as an extrinsic element, neutral or of no consequence. The majority are displayed on lilliputian LCD monitors and pre-smartphone personal devices. Race Riot (2001), a four-second loop of an NBA player curled up on the court floor—one among many auguries of the GIF—plays on the 2.5-inch fold-out screen of a late-nineties Sony Handycam.

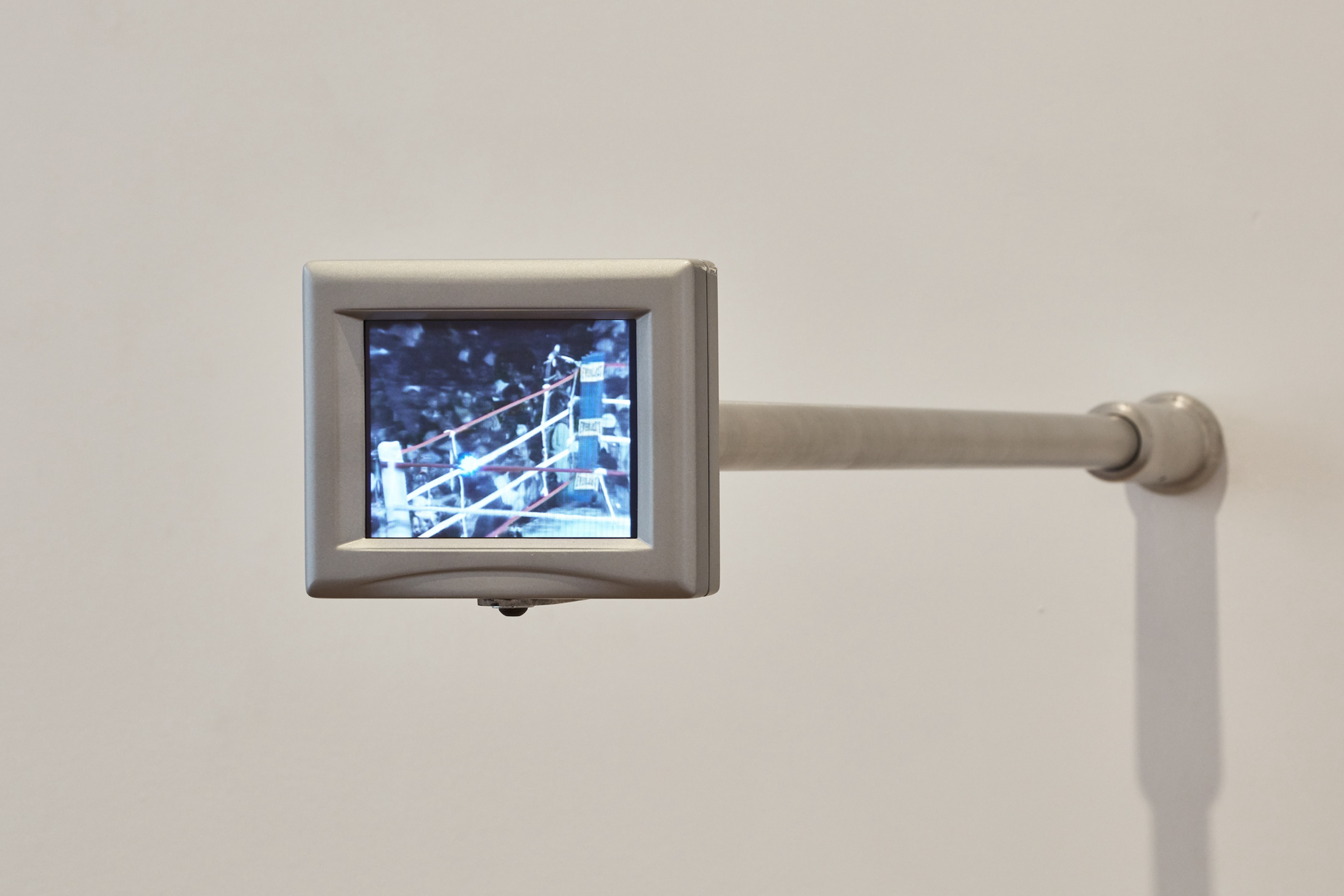

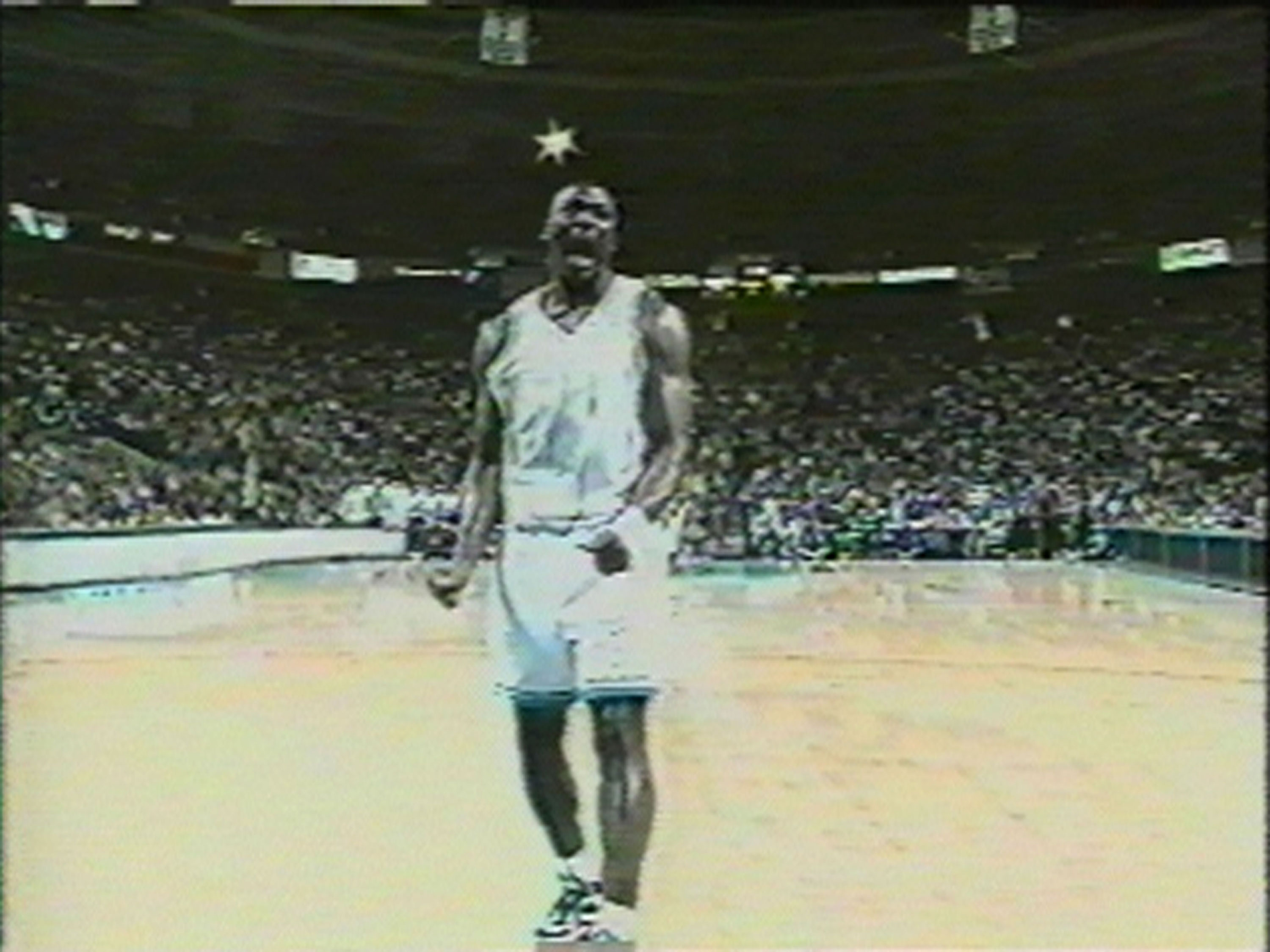

Thankfully, “Prologue…” does not allow these miniature media works to be dwarfed by Pfeiffer’s larger installations, and grants them the precedence they deserve. In the exhibition’s first room, three stand alone: on opposing walls, two consumer-grade Sony projectors, circa 1996, are mounted to security-cam arms, each pointing inward. At such a short distance, the projected works flicker at only a few inches across. The Pure Products Go Crazy (1998) shows a tiny Tom Cruise in Risky Business (1983), quivering ad infinitum on a couch; Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon) (1999) replays broadcast footage of a black NBA player in a white jersey, hands clenched, hollering in apparent triumph. Pfeiffer has removed all markings from his jersey and excised all other players; the man paces alone on his Platonic court. Watched on loop, his open-mouthed scream molders into Baconian agony. Between these two is John 3:16 (2000), a 5.6-inch LCD monitor attached to a straight metal arm. For a couple of minutes, an orange basketball remains center-frame, sewn into a single entity from countless clips, a comet streaking across televised time.

“I think it’s an almost perfect match, TV and sports,” the media theorist Neil Postman once mused. “There’s almost no content… it’s all form, all dynamic imagery.”2 Pfeiffer clearly takes pleasure in the telegenic power of professional basketball, soccer, hockey, football, and boxing, but he also knows how to pull the thread of their politics. His low-resolution and Beckettian loops accentuate the motions of athletes’ (mostly Black) bodies, sweating and fighting before amorphous, madding crowds. Even when the athletes have been removed, the dialectic is distinct. (“Birth of freedom,” after all, echoes an emancipatory promise made by Abraham Lincoln during the Gettysburg Address, and “prologue” suggests that it has yet to be fulfilled.)

As his career progresses, Pfeiffer plunges further into these discourses, distilling works into studies of, say, the arena, the celebrity, the cinematic, the spectator, the laborer, the body of color. At times, it can be too roving. But his miniatures—a vast Olympic stadium and a tiny campsite encircled by leafy jungle, for two—are marvels of meticulous dedication, and feel like cousins to his compact videos and scrupulous Photoshopping. Those screens and scenes alike belie a desire to zoom out and see the world in, as Claude Lévi-Strauss said, “intelligible dimensions.”3 Each is appropriative in an honest way, drawing attention to its inherent constructedness instead of boarding it up.

The more recent Art21 episode shows Pfeiffer in the latest phase of his career. He’s attending a University of Georgia football game, amid the throngs of red-clad fans, casing the stadium as he consults with a crew of videographers sporting high-powered DSLRs. The artist was embarking on a new project, here shown in a theater-like presentation. Red Green Blue (2022) is over thirty minutes long and digitally projected onto a large screen in crystal-clear high-definition. Sequences of still and handheld shots explore the dense fanfare and mechanics of Division I football, collecting close-ups of band conductors and benched players, painted chests and Skycam pulleys. It’s rhythmic and spellbinding, and it succeeds in its scrutiny of collective ritual. But seeing Pfeiffer treat both organic footage and state-of-the-art screen projection as clear windows on the world begs the question: is the medium no longer the message? Pfeiffer found his groove during digital media’s antiquity, and his tools were tethered to a certain time and history. Of course, “Prologue...” has no epilogue; we're left to wonder how that agile critique will adapt to the birth of new realities.

This article was adjusted on December 16, 2023 to correct a description of Dutch Interior (2001).

Niklas Maak, “On Paul Pfeiffer,” in Paul Pfeiffer, ed. Octavio Zaya (ACTAR/Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Castilla y Leon, 2009), 45.

Michael Goodwin, “TV Sports: One Critic’s View of Perfect Marriage,” The New York Times, March 19, 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/19/sports/tv-sports-one-critic-s-view-of-perfect-marriage.html.

See Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, trans. George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd (Paris: Plon, 1962): https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/levistrauss.pdf.