“If you’re in trouble, you don’t think straight,” Ibrahim, an electrical engineer with the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) described Ghana’s recent electricity crises. In a meeting room on the fifth-floor of the Electro Volta House building, our windows looked out on Accra’s Black Star Square, a modernist public square built by the country’s first president and pan-African statesman Kwame Nkrumah in 1961 in celebration of Ghana’s independence from colonial rule. On the wall dangled a monthly calendar that featured newly completed electrical substations across the country. Like many of the other employees I met there in late 2019, Ibrahim wore a button-down shirt featuring the ECG logo, tailored for him with fabric printed in recognition of the company’s fiftieth anniversary.

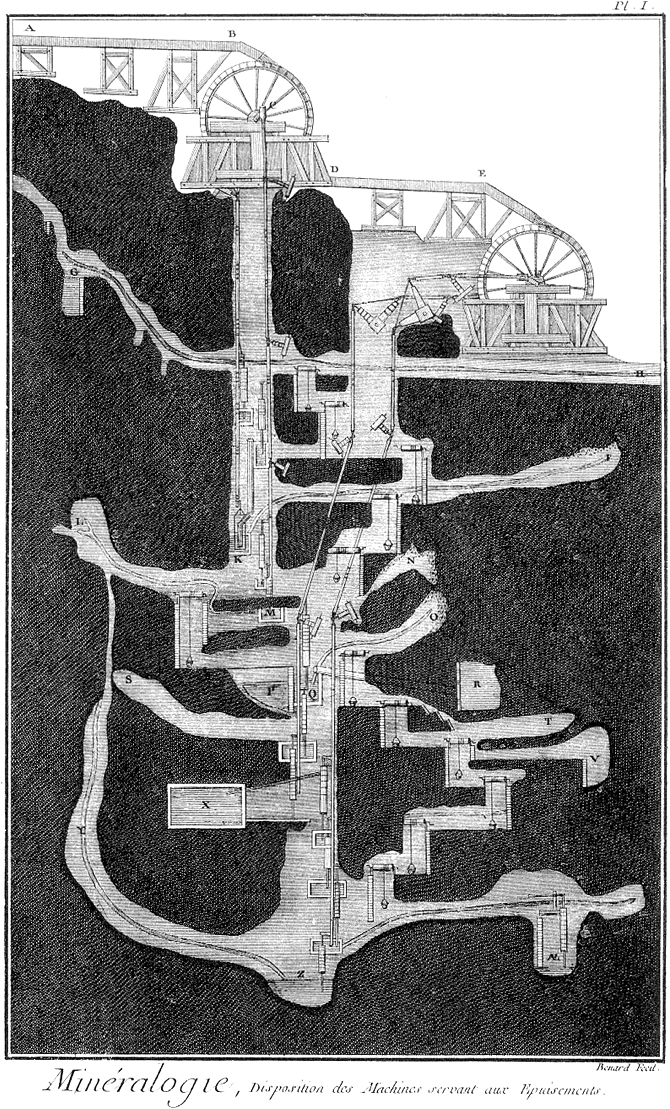

Until the year 1997, state-owned hydroelectric power plants produced all of Ghana’s electricity.1 In the words of historian Stephan Miescher, the opening of Ghana’s Akosombo Dam in 1966 and creation of Lake Volta—the world’s largest human-made lake by surface area and the fourth largest reservoir by volume—“produced different temporalities of an industrialized future that would transform the country’s rural past and create new cities, factories, and infrastructures.”2 In the inauguration ceremony, Kwame Nkrumah announced: “It is in this spirit of fruitful collaboration for a better world for all that I…inaugurate the Volta River Project. Let us dedicate it to Africa’s progress and prosperity. Only in this way will Africa play its full part in the achievement of world peace and for the advancement of the happiness of mankind.”3

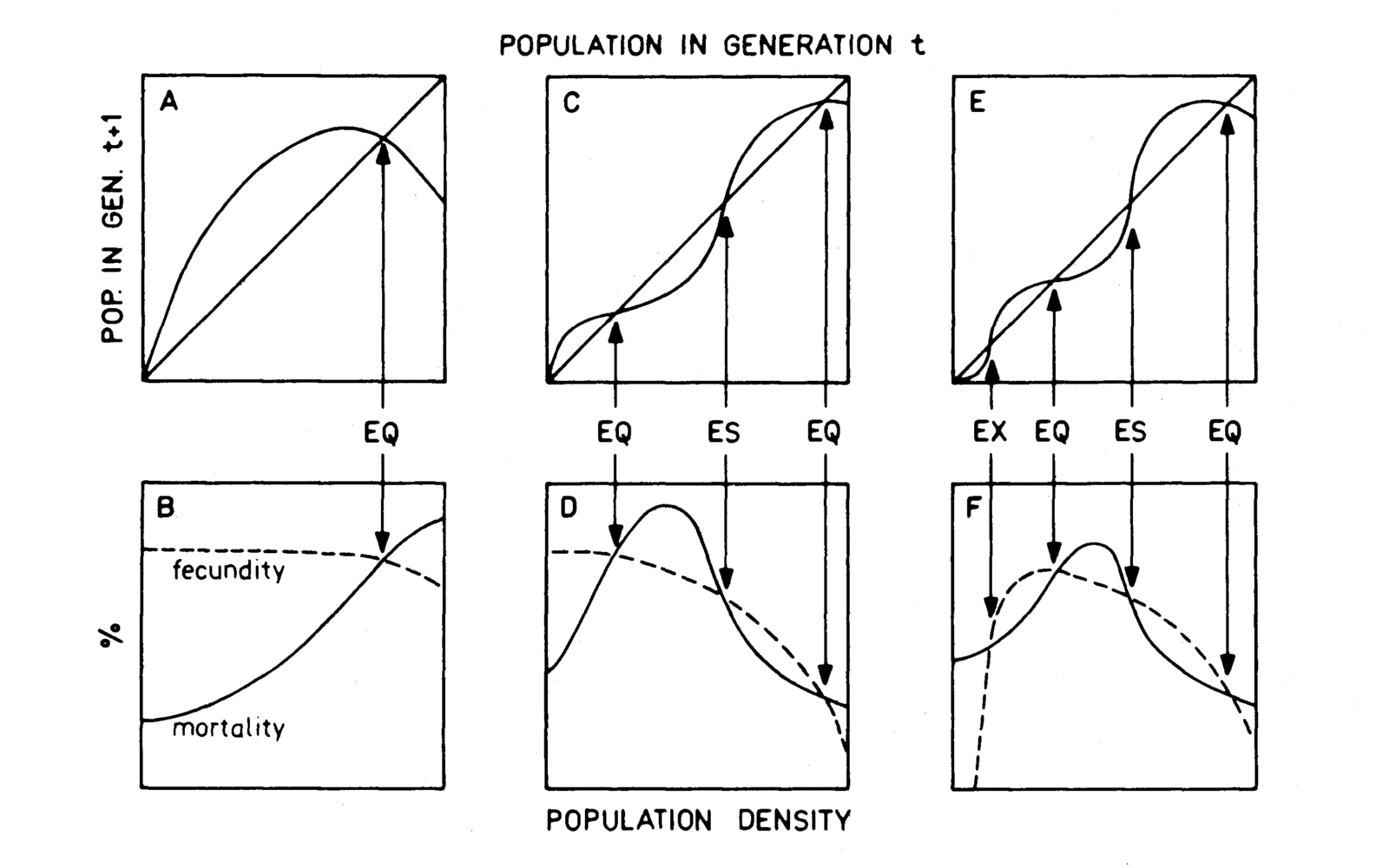

Inadequate rainfall and rising temperatures associated with climate change, however, have negatively impacted the hydroelectric power station at Lake Volta, at times completely incapacitating it.4 As a result, new power producers have entered the Ghanaian electricity market since the early 2000s, mostly thermal power stations that rely on natural gas, stockpile light crude oil, and burn heavy fuel oil. Unlike Nkrumah introducing the Akosombo Dam, these power producers have not offered teleological narratives about progress, but rather quick, stopgap solutions.

Between 2012 and 2015, an electricity crisis resulted in unprecedented levels of load shedding throughout Ghana. Power for industries and homes was out for 24 hours at a time, and turned back on for only 12-hour periods. Dumsor, the name given to the crisis that means “off and on” in Twi, was brought about by low water levels in hydroelectric dams due to climate change, disruptions to natural gas flows from Nigeria, and alleged mismanagement of the grid infrastructure. In response, Ghanaian decision-makers such as Ibrahim saw a further expansion and diversification of the country’s energy portfolio as a possible solution to the crisis, shifting the nation’s energy production portfolio further away from hydropower and towards fossil fuels.

The Osman Khan floating power plant, currently producing electricity for Ghana, was built as a bulk carrier by Samsung Shipbuilding & Heavy Industries in Geoje, South Korea in 2000, and owned and managed by the Australian company Teekay Shipping until 2014. Karpower engineers converted the bulk carrier into a floating power plant in the Sedef Shipyard in Tuzla, Istanbul. Photo by the author, Tema, July 2018.

In seeking to resolve dumsor, the Electricity Company of Ghana, the sole electricity distributor servicing the south of Ghana, signed forty-three power purchase agreements with different vendors.5 As a result, new independent power producers from countries such as Turkey, China, and the United Arab Emirates set up powerplants in Ghana, using heavy fuel oil and natural gas. “Prices were so high during the emergency,” Ibrahim explained. “And many of the contracts we signed stated that we would pay whatever we agreed, which was double or more what we would usually pay, for the next decade.”

Fossil fuel-powered thermal plants today produce about two thirds of Ghana’s total electricity. “We over-solved the problem,” a former junior member of the Energy Commission, a regulator body responsible for electricity licensing, reflected back on the crisis. Between 2015 and 2019, Ghana’s electricity supply went from 2800 megawatts—which was sized to the demand placed on the grid—to over 5000 megawatts. The new powerplants triggered an excess of electricity on the country’s grid. What has taken place in Ghana since the turn of the twenty-first century and accelerated as a result of the final episode of dumsor is therefore best understood not as an energy transition, but an energy accumulation.

Humans have consistently added new energy sources to the civilizational mix.6 The use of certain fuels is sometimes reduced, as they prove undesirable or inefficient. But in contrast to what is suggested by conventional narratives around “energy transition” today, rarely are they completely abandoned or replaced. Recognizing the linearity of this dominant narrative, an energy specialist I met at the University of Ghana, Paul, mentioned “maybe we are transitioning in reverse.” And indeed, many of the natural gas and heavy fuel oil powered generating plants in Ghana were previously used in countries like China and Turkey, uprooted, broken down to pieces, and carried in cargo ships to now serve the Ghanaian grid.

Many independent power producers entered the Ghanaian market on “take-or-pay” contracts, where the Electricity Company of Ghana either bought electricity from a producer or paid the producer a penalty for electricity it did not use. “A hungry man does not need a table full of rice,” Joseph from GridCo described during an interview in his Tema office in December 2019. “Why build 5000 megawatts when you can’t consume it?” 2300 megawatts of Ghana’s electrical energy is produced on a take-or-pay basis. While some wondered why the Ghanaian government couldn’t use this excess for productive projects, such as rural electrification, the government has paid over $500 million per year for electricity it did not consume.

In 2017, a news report revealed that the contract with the Emirati thermal power station AMERI had been overpriced by $150 million, and eventually led to the removal of the Energy Minister Boakye Agyarko from his position.7 Another corruption scandal broke out in April 2020, when the US Securities and Exchange Commission claimed that “Asante Berko, a former executive of a foreign-based subsidiary of a US bank holding company, arranged for his firm’s client, a Turkish energy company, to funnel at least $2.5 million to a Ghana-based intermediary to pay illicit bribes to Ghanaian government officials in order to gain their approval of an electrical power plant project.”8

Given the context of mistrust and corruption, decision-makers in the country have been calling for a renegotiation of these contractual terms.9 In the meantime, new energy sources and relations continue to be developed. Of the 5000-megawatt electricity production capacity on the grid, only 40 megawatts currently come from solar, produced by Chinese companies in Winneba. An additional 100 megawatts is currently under construction in Bui. A second strand of solar electricity generation has taken place through rooftop solar panels, which have emerged as viable options for individuals and institutions with access to upfront capital. Many industrial facilities have also built rooftop solar panels, cutting their reliance on the Electricity Company of Ghana by half.

As a consequence of losing more of its steady and paying clients to rooftop solar panels, and being trapped in take-or-pay contracts with independent power producers, the Electricity Company of Ghana had been forced to increase tariffs. “Imagine industrial facilities as the business class passengers on a plane,” remarked Belinda, a young energy professional with the Energy Commission. “They subsidize flights for economy class passengers, and in turn receive special treatment, say, they’re offered champagne. Industrial consumers in Ghana subsidize residential consumers, and complain that they are not receiving any special treatment. We give them no champagne, so they slowly reduce their reliance on the grid.”

In this context, some hope new business models will come to the rescue. “Have you seen the solar map of Ghana?” Raymond, a legal advisor to GridCo, asked me enthusiastically. “We are missing opportunities by not building solar here.” He celebrated the green financing programs that some Ghanaian banks had recently started, offering funding for domestic and institutional consumers bidding to build rooftop solar panels. “Once you prove that your project is lowering emissions, your interest rates fall. There are incentives for building solar,” representatives at Ghana’s Cal Bank confirmed. Dressed in polo shirts advertising their green financing programs, four Cal Bank men told me that they offer three-to-five-year loans for rooftop solar projects, but have had trouble attracting individuals with stable jobs for these loans.

The future does not hold the promise of stable flows of electricity on the grid for energy professionals in Ghana. Instead, energy professionals anticipate power outages. Joseph, a senior electrical engineer with GridCo, told me that he lived very close to the headquarters of the grid company in Tema because he wanted to arrive at the control room as quickly as possible when a blackout occurred. A devoted member of one of the most popular charismatic churches in West Africa, he summarized his relationship to dumsor by using an analogy: “Can you kill the devil? The world would be a very beautiful place if you could kill the devil. But you can’t kill it. You have to stay away from its control.” According to Joseph, reduced flows and increasing costs of electricity will continue to characterize the Ghanaian grid for the years to come. Regardless of their countless complications, Joseph hoped that energy accumulation would temporarily manage to keep the devil away.

Albert K. Awopone, Ahmed F. Zobaa and Walter Banuenumah, “Assessment of optimal pathways for power generation system in Ghana,” Cogent Engineering 4, no. 1 (2017).

Stephan Miescher, “Nkrumah’s Baby: The Akosombo Dam and the dream of development in Ghana, 1952–1966,” Water History 6 (2014): 341.

Edward S. Ayensu, Lake of Life: Celebrating 50 Years of Volta River Authority (Accra: Volta River Authority, 2013), 19.

Jonathan Silver, “Disrupted infrastructures: An urban political ecology of interrupted electricity in Accra,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 5 (2015): 984–1003. See also: Thomas Yarrow, “Remains of The Future: Rethinking the Space and Time of Ruination through the Volta Resettlement Project, Ghana,” Cultural Anthropology 32, no. 4 (2017): 566–591.

Northern Electricity Distribution Company (NEDCo), the second electricity distribution company in Ghana, services the north. Because the northern part of the country has fewer industrial facilities, the power supply of NEDCo is significantly lower than ECG, rendering ECG the most significant actor in electricity distribution. Since the unbundling of the country’s electricity sector in the early 2000s, these two companies only serve as distributors and have no power production capacity.

Jennifer Wenzel, “Forms of Life: Thinking Fossil Infrastructure and its Narrative Grammar” (unpublished manuscript).

Synnøve Åsebø, Rolf J. Widerøe, and Amund Bakke Foss, “Exposed: John Mahama brings Ameri Group to Namibia,” VG, November 13, 2017, ➝.

For more information on the case, see: “SEC Charges Former Executive of Financial Services Company with FCPA Violations,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, April 13, 2020, ➝. For Berko’s response, see: “Asante Berko rejects bribery allegations by U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission,” Joy Online, April 14, 2020, ➝.

See, for instance: “Government to renegotiate ‘take-or-pay’ contracts in the energy sector,” Ghana Business News, July 30, 2019, ➝.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)