May 20–November 26, 2023

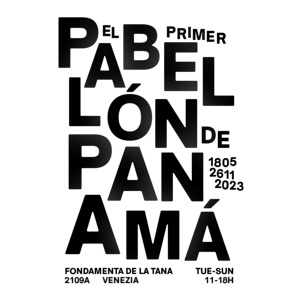

The Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Panama, the commissioned curator Aimée Lam Tunon and creative director Jasper Zehetgruber announce the opening of the Panamanian Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia 2023.

Exhibition introduction

Since antiquity, the tropics have been widely recognized as a symbol of exotic beauty, dangerous animals, and luxuriant vegetation. Portrayed as a faraway place, with different histories, languages, and cultures, this geographical area represents an amalgamation of qualities that define the fantastic, and mysterious nature of reality. Often considered from a western perspective as a hostile environment to progress, the tropics represent everything that Europe and the United States are not (Lasso, 2019), the antithesis to civilized modernity. This exhibition provides a counter-narrative to this status quo, with Panama as a case study for a future vision of a “tropical” nation, by combining its various historical influences.

Space I: Separation for control

During the early 19th century, as Spanish rule over the isthmus of Panama dwindled, the French were the first to attempt the construction of a canal. This effort resulted in a death toll of over 22,000 lives, largely attributed to malaria and yellow fever, immortalizing Panama as a place of danger and disease. Soon after, the United States entered the new nation of Panama with a distinctive vision of imperial administration—the Panama Canal Zone. Less a colony than an engineering enclave, the ten-mile strip of land meant to stand in contrast to its natural and social environment, defining a landscape of modernity. Within these confines, an “othering“ narrative and ideology led to a demarcation of sanitated areas, domestication of the jungle, racial segregation, and depopulation of the “zone” from Panamanians and their cities. In this first space of the exhibition, a low ceiling and narrow walkways limited by mosquito nets create an immersive experience of the claustrophobic, segregative atmosphere of the Panamanian colonial era for the visitors.

Space II: The magical walkway

The depopulation of towns and destruction of Panamanian landscapes due to the construction of the canal evoked feelings of nostalgia for the environment that was and the desire to preserve its image in the collective memory. This is reflected in the recurring theme of the landscape in post-colonial literature. “Caribbean writers have always had only one referent available to shape the theme and the language of their works: the landscape – insular, oceanic, luxurious, mysterious, and ever-resistant to conquest and appropriation by mapping or “realistic” descriptions. (…) This is one of the basic precepts of the magical realist text. Only the magic and the dream are true because they are the only discursive elements able to present the unpresentable, to speak the unspeakable where the realistic text fails.” (Arva, 2010) Following this line of thought, the courtyard provides a safe space for reflection: Trees recovered from beneath the waters of the artificial lakes of Panama tell the story of the erased and submerged communities of Panama, while avoiding direct confrontation with colonial trauma.

Space III: Separation for protection

Barro Colorado Island (BCI) is a unique space, a hilltop that became isolated in the middle of the Panama Canal when the waters of the Chagres River were dammed to create Gatun Lake, the main passage of the waterway. Set aside by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute as a nature reserve since 1923, today, exactly 100 years later, this island is the most studied tropical forest in the world. Frequently advertised as a living scientific “archive” and “laboratory” in which the landscape became both—an object and repository of scientific knowledge. Discussing the purportedly opposing perspectives toward BCI as “a fragment of authentic tropical nature standing at the crossroads of the world” and its position as “a shadow of the former Canal Zone“, this last room of the exhibition questions the history, inclusivity, and legacy of this tropical station. What is its role in the conservation of local and global biodiversity and ecological research? This last room is a space of listening, to critically reflect on the connections between control and protection and to imagine a future vision for science and modernity in Panama and beyond.

*Images above: (1) Artificial Lake Gatun at its lowest recorded water levels in February 2016. As part of the Panama Canal, it supplies most of the Panamanian population with drinking water. Fred R. Conrad for the New York Times, 2016. (2) Sonar scan of submerged forests in Lake Gatun. Image created as part of detailed forest mapping, in the context of the Panama Canal expansion. Triton Timber Group, 2015.