4.a Present state of conservation

The right of return is a universally recognized human right of all persons. It was first inscribed in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights as Article 13(2), stating: “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” The right of return was first inscribed within the realm of international law when, on December 11, 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194, stating that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.” This inalienable right has since been reaffirmed in more than one hundred UN resolutions.

Despite its legal recognition, the right of return for Palestinian refugees has been postponed for almost seven decades. This status quo must be challenged so that it can finally be brought about. We must also think projectively, into the future, and imagine what would happen if the right of return were to be granted. What would happen to the camps? Would they be destroyed and abandoned? Would they continue to be inhabited, or reused for other purposes?

In order to tackle these questions, we need to firstly destabilize the right of return’s political foundation: the concept of exile. Exile is not a condition that needs, or can be cured by, return. Exile is a pervasive social condition that is radicalized in the case of refugees. The erosion of rights of southern European citizens brought about by a state of austerity derives from the same regime that oppresses, expropriates, and controls refugees. Young people living in global cities around the world suffer from a similarly permanent condition of precarity. Rather than perpetuate a false dichotomy between citizens and refugees, a new alliance between what might appear to be radically distinct groups must be imagined. Exile must be thought of as a radical new foundation of civic space.

Exile and nationalism both stem from and respond to the same modern condition of alienation and the subsequent search for identity. Whereas nationalism tries to create collective identities of belonging for an imagined community, a political community of exile is built around the common condition of non-belonging, of displacement from the familiar. As a political identity, exile opposes the status quo, confronts a dogmatic belief in the nation-state, and refuses to normalize the permanent state of exception in which we are all living.

The exile knows that in a secular and contingent world, homes are always provisional. Borders and barriers, which enclose us within the safety of familiar territory, can also become prisons, and are often defended beyond reason or necessity. Exiles cross borders, break barriers of thought and experience.1

The second concept in need of destabilization is conservation. For some, conservation is an architectural discipline that freezes time, space, and culture; one that reduces buildings to spectacular objects for contemplation and consumption. Yet conservation today pertains to the contested space in which identity and social structures are built and demolished. In recent years, architectural conservation has become a field of knowledge and practice able to reframe our understanding of culture, history, and aesthetics. What follows are four examples of how radical and political understandings of conservation have been put into practice by residents of Dheisheh.

Conservation through demolition

One of the original shelters in the site. Photo: Campus in Camps

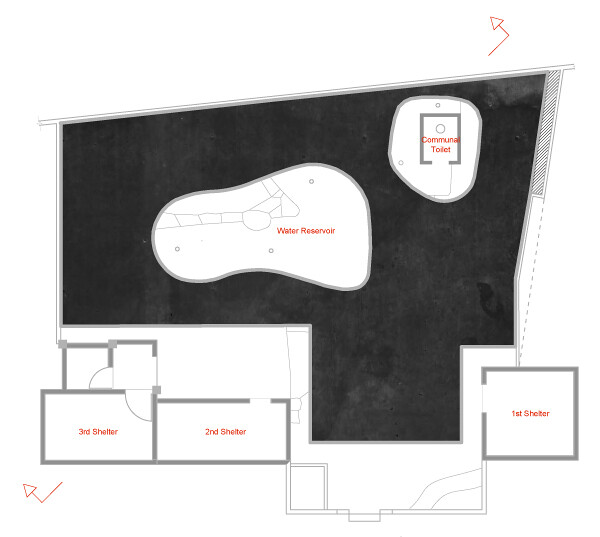

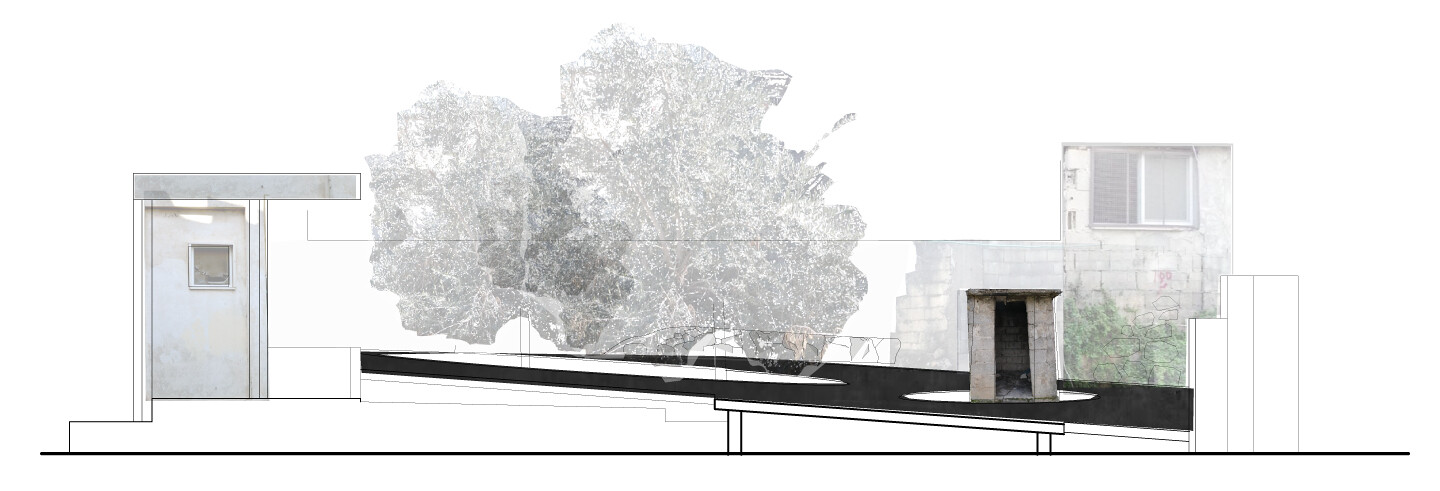

Behind a closed gate, a plot in eastern Dheisheh contained the foundation and history of the camp. Three original UNRWA-built structures from the 1950s stood—three shelter-rooms, one communal toilet, and a water reservoir—no longer in use. Recognizing the sensitive and politicized context, a collaborative design process for deciding what to do with the site unfolded among local inhabitants, Campus in Camps participants, and DAAR. Considering the value of the architectural structures and their symbolic place within the collective memory of camp residents, a non-intrusive intervention was decided upon to both preserve and bring new uses to the site. The project materialized as a black frame—a fifteen-centimeter-thick reinforced concrete platform—surrounding the historical structures, leaving them intact as a sign of respect for the past in this new beginning.

Site plan with platform

Site section with platform

Months were spent with the site’s neighbors and owner discussing the aim of the project. With their consent, activities such as concerts and film screenings began being hosted on the site, and an agreement was signed between the popular committee and the owner to guarantee collective use of the land for two years. Construction began by excavating foundations, but, after ten days, one member of the large family who owned the site prevented the laborers from working on it. Despite the initial agreement, he had changed his mind and decided to sell the abandoned plot after it had received so much renewed attention. The popular committee and leaders of the camp spent several weeks with the family trying to find a solution to preserve the site, but in a single night all the shelters were demolished, shocking not just to the people involved in the project but also to the wider community. Through the collective process that had been generated on and around the site, the present was revealed by its erasure, making clear the importance of the urban fabric as a historical site of narrative and value.

Conservation through reversal

Detour, 2015. Photo: Campus in Camps

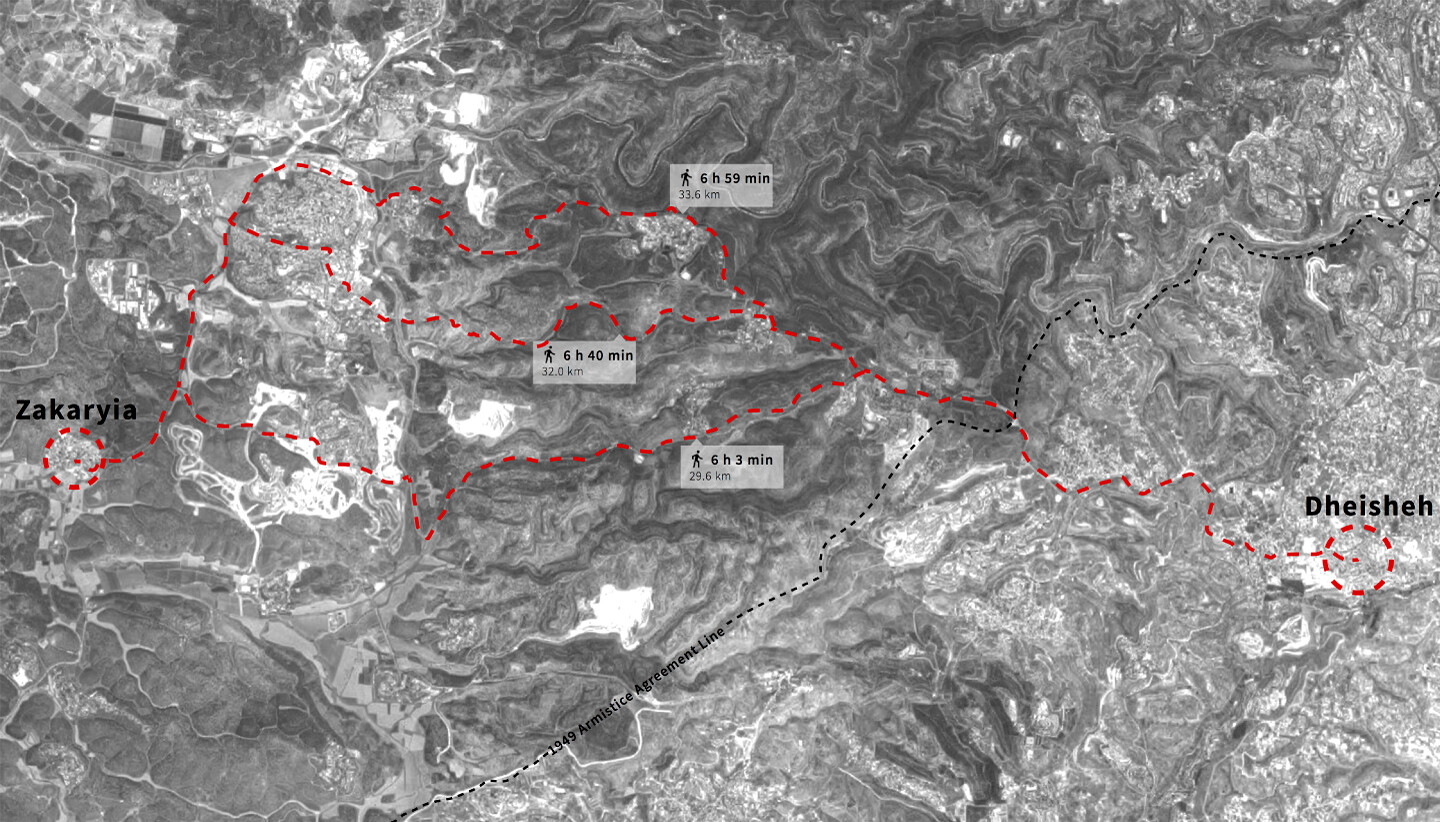

The notion of “routes” or “cultural itineraries” as being part of cultural heritage started to emerge at the beginning of the 1990s. Heritage routes are considered to bring “strengths and tangible elements, testimony to the significance of the route itself and offering a privileged framework in which mutual understanding, a plural approach to history, and a culture of peace can all operate.”2 In this sense, Campus in Camps performatively reenacted the route of displacement that inhabitants of Zakaria took from their village to Dheisheh in 1948.3

Routes of return from Dheisheh to Zakaryia

Dheisheh is visited daily by hundreds of activists, who, with their international passports, can cross territorial borders that Palestinians cannot. The establishment of this route of return also imagines a possible reversal of displacement and serves as an antidote to the commodification of heritage sites.

Conservation through resistance

Murad is a third-generation refugee and member of the Odeh family. About two years ago, he finished his Master’s degree in the United States and decided to go back to Dheisheh, where he was born and raised. Like many others before him, he was forced to adapt to a life in exile under occupation. He thought about living outside the camp, but realized “I will feel lost … I only wish I could build my home in my village of origin.” As the two generations before him, Murad started to think about building onto the family house in the camp. After sharing his worries with DAAR about building on top of a poorly built house with weak foundations, and after consulting with a structural engineer, we found that the home could support another floor, which Murad asked DAAR to design. He wanted the house to be ready for his wedding with Maia, a Jewish American woman from Minneapolis. With very little money but with support from the camp, the extension was built. Designing the house for Murad and Maia was a preservation of the values of a family who has been faced with intolerable conditions for generations.

Conservation through reconstruction

The prolonged political exceptionality of refugee camps has produced a specific urban and social condition. Architecture in this context is usually called on to intervene only as a technical solution, like designing smart tents or mobile structures, and rarely used for its power to address and express political and social problems. In discussion with Campus in Camps participants, an urgency emerged to materialize, to give architectural form, to the permanent temporariness of the refugee camp.

When we think about refugee camps, one of the most common images that comes to our mind is an aggregation of tents. However, more than sixty years after their establishment, Palestinian refugee camps are constituted by a completely different materiality. Tents were first reinforced and adapted with vertical walls, then substituted with shelters, and, later, new houses made of concrete were built, making camps dense and solid urban spaces.

The project tries to inhabit the paradox of how to preserve the tent’s symbolic and historical value. Because of the degradability of the tent material, these structures do not exist anymore. Therefore, the re-creation of the tent out of concrete is an attempt to preserve the cultural and symbolic importance of this archetype in the narration of the Nakba and the political condition of exile. In June 2015, the “concrete tent” was inaugurated as a gathering space for communal learning in the garden of Al Finiq Cultural Center. The concrete tent is a hybrid, between a tent and a concrete house, temporary and permanent, soft and hard, movement and stillness.

To force people to live in miserable conditions does not bring them closer to return. To negate their right to a life of dignity is just another form of violence imposed on the most vulnerable segments of Palestinian refugees. We need to seriously consider why it is that the right of return should negate the existence of the camp or call for its destruction. Claiming the camp as a heritage site is a way to avoid the trap of being stuck either in the commemoration of the past or in the projection of an abstract, messianic future. Claiming the history of the camp is a way to start articulating the right of return. The achievements of the present are not an impediment to the right of return, but, on the contrary, a step toward it.

Refugee Heritage was made possible by the Decolonizing Architecture course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden.

Category

Refugee Heritage is a project by DAAR, edited and published by e-flux architecture and produced with the support of Campus in Camps, the Foundation for Art Initiatives, the 5th Riwaq Biennale and the Decolonizing Architecture course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden.