What do we mean when we talk about “history” in an architectural context? Or, to ask the question in a slightly different way, what can “history” do for architects? This question has been answered differently across various cultures and times, but for the time being I will limit myself to considering four ways that history can operate with respect to architecture. First, history can be posited as a collection of objects: buildings can be deployed as precedents, and used to constitute a canon. Second, history can be a lens through which to survey the broader characteristics of a culture and society: buildings can be studied to shed light on the social conditions they depend upon and foster, or the values they promote or betray. Third, history can be understood as unveiling a set of abstract principles, or axioms, and used to generate theory. And fourth, history can be construed as a practice, a form of architectural thought, not unlike sketching and modeling.

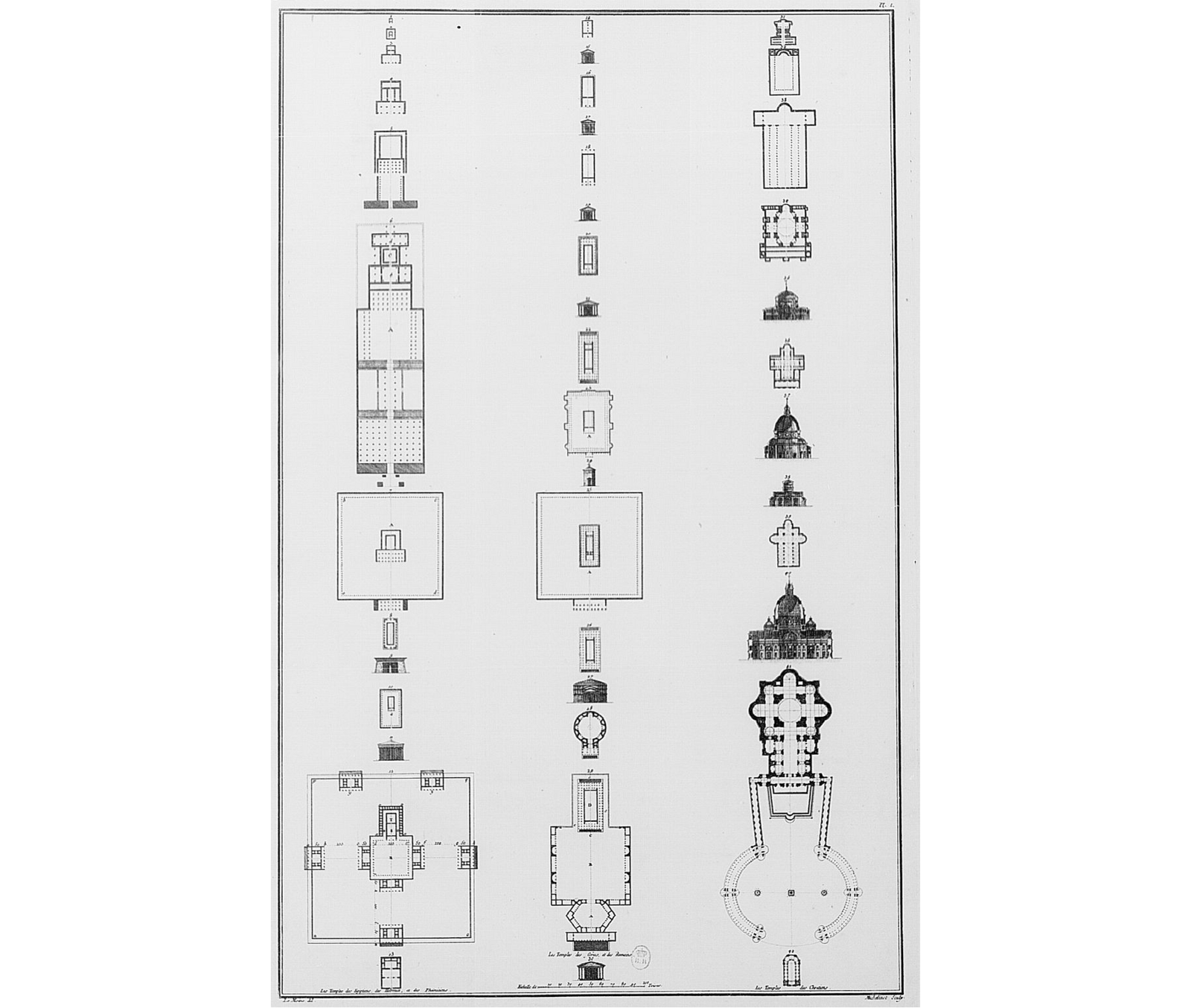

It is the first definition—history as a collection of objects—that is both the most widespread, and the most problematic in terms of design education. When asked about the form and content of their history courses, almost all architecture students (particularly in the United States) will mention the survey: a wide-ranging, chronologically organized, stylistically-categorized overview of buildings and projects that the discipline has deemed worthy of attention. For as long as the classical tradition held sway, the use of such knowledge seemed clear: the “great buildings” of the past contained lessons that were fundamental to the perpetuation of architecture as a discipline. Aspiring architects were required to be well versed in this form of history because their creativity was understood to be intimately bound up with the pursuit of architectural questions that were constitutive of the discipline itself.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the search for a style that expressed “the spirit of the age” demoted classicism to just one of a number of possible styles. The assumption that the classical tradition constituted a vital and evolving inheritance began to lose its hold. Modernism, whose conflicted relationship with history required that its actual indebtedness to the past be forcefully denied, dealt this assumption its final blow. History was cast as an impediment to innovation since its study reduced students to mere copyists, and encouraged them to encumber functional forms with unnecessary ornamentation. Although many of Modernism’s proclamations were exposed as myths decades ago, the fear that history might somehow stifle creativity has been remarkably resilient, continuing to color the attitudes of some students even today.

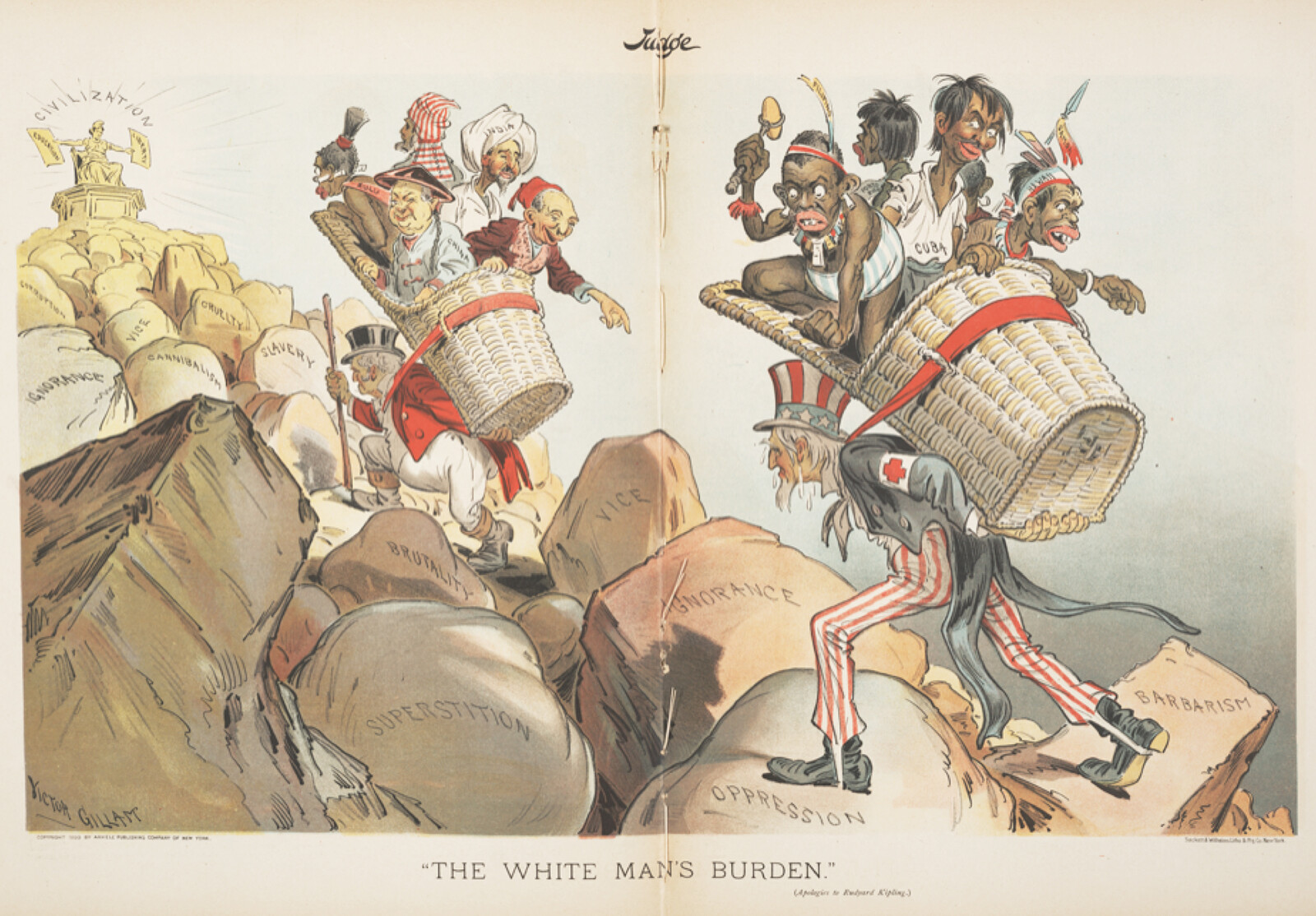

With the rise of a social history of art in the postwar period, the survey began to address issues that broadened the notion of the discipline, exploring the ways in which architecture relates to culture and society. Questions of reception and use became as important (and often even more so) than ones of authorship and style. Efforts in more recent years to further diversify and globalize the survey by including works of architecture by both men and women, known and anonymous architects, and from African, Asian, Australian, and South American countries as well as European and North American ones have simultaneously expanded and challenged the very notion of the canon. At the same time, theoretical and built works that seek to dissolve architectural objects into landscapes, fields, networks, infrastructures, and affects have even more fundamentally challenged a traditional object-based understanding of architectural history.

Yet even in the most progressive of courses—ones that assume a global definition of architecture and set buildings and their users within a rich social, cultural, political, and intellectual context—the nature of the relationship between history and design remains elusive. All too often the link that is assumed to exist between exposure to a sanctioned collection of objects and the design work happening in studio is passed over in silence. To complicate matters further, if the role of history is assumed to depend on its “relevance” to design, then history runs a high risk of being dismissed out of hand when it includes material whose connection to contemporary design concerns is not immediately apparent. All too often, the survey ends up making “history” into something students are told they must ingest because it is somehow good for them, but not presented as anything they might remotely want to sample.

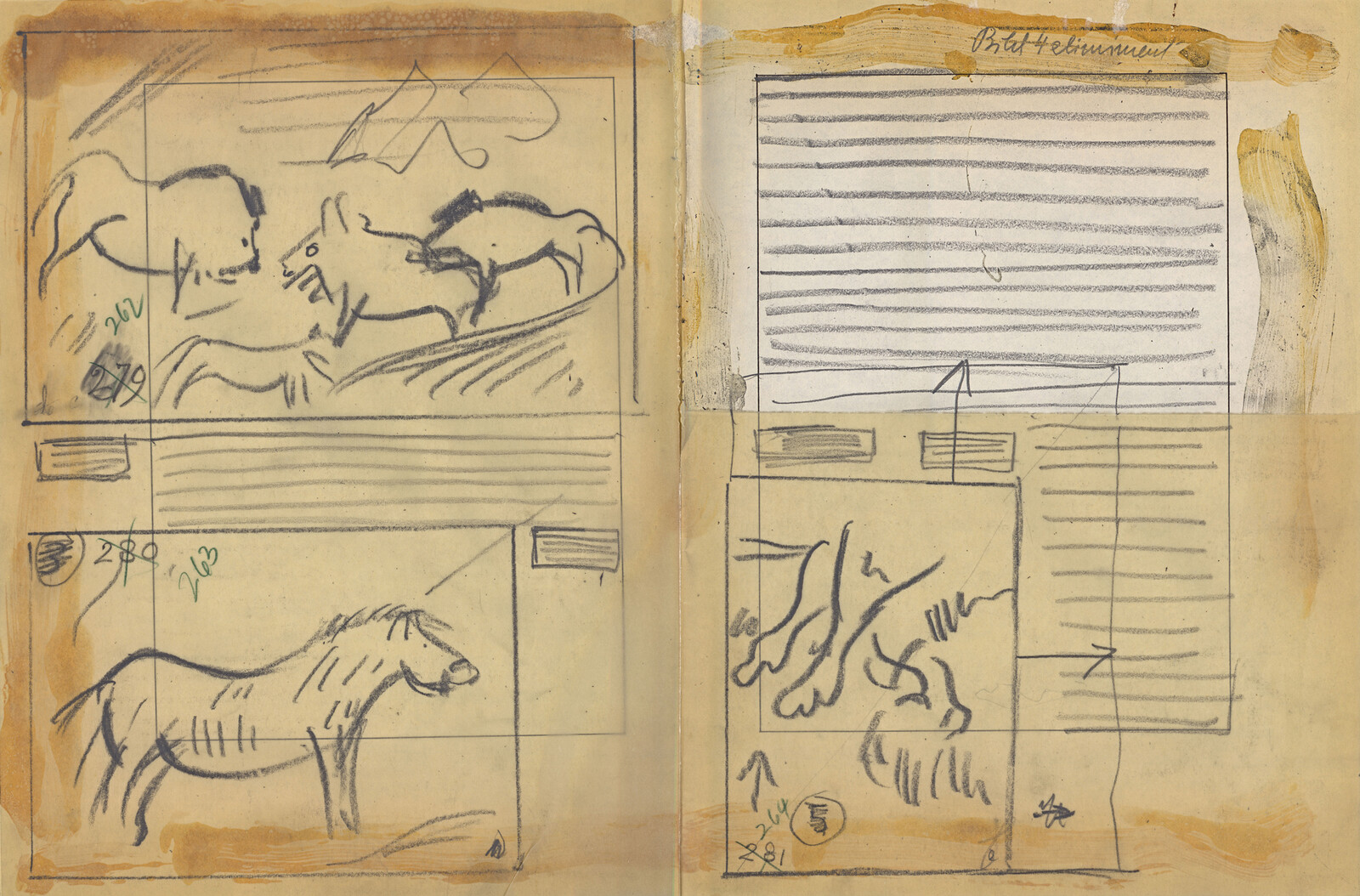

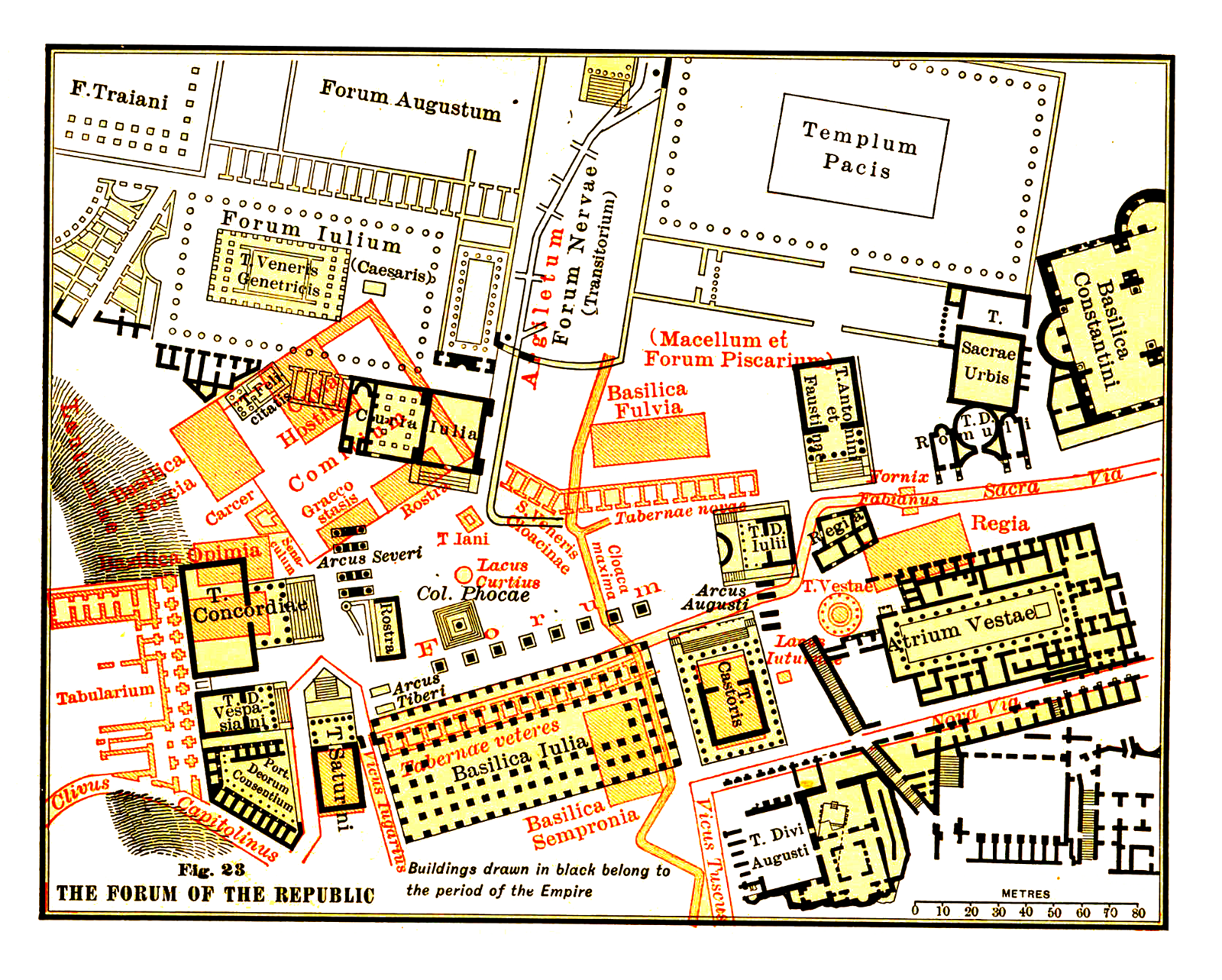

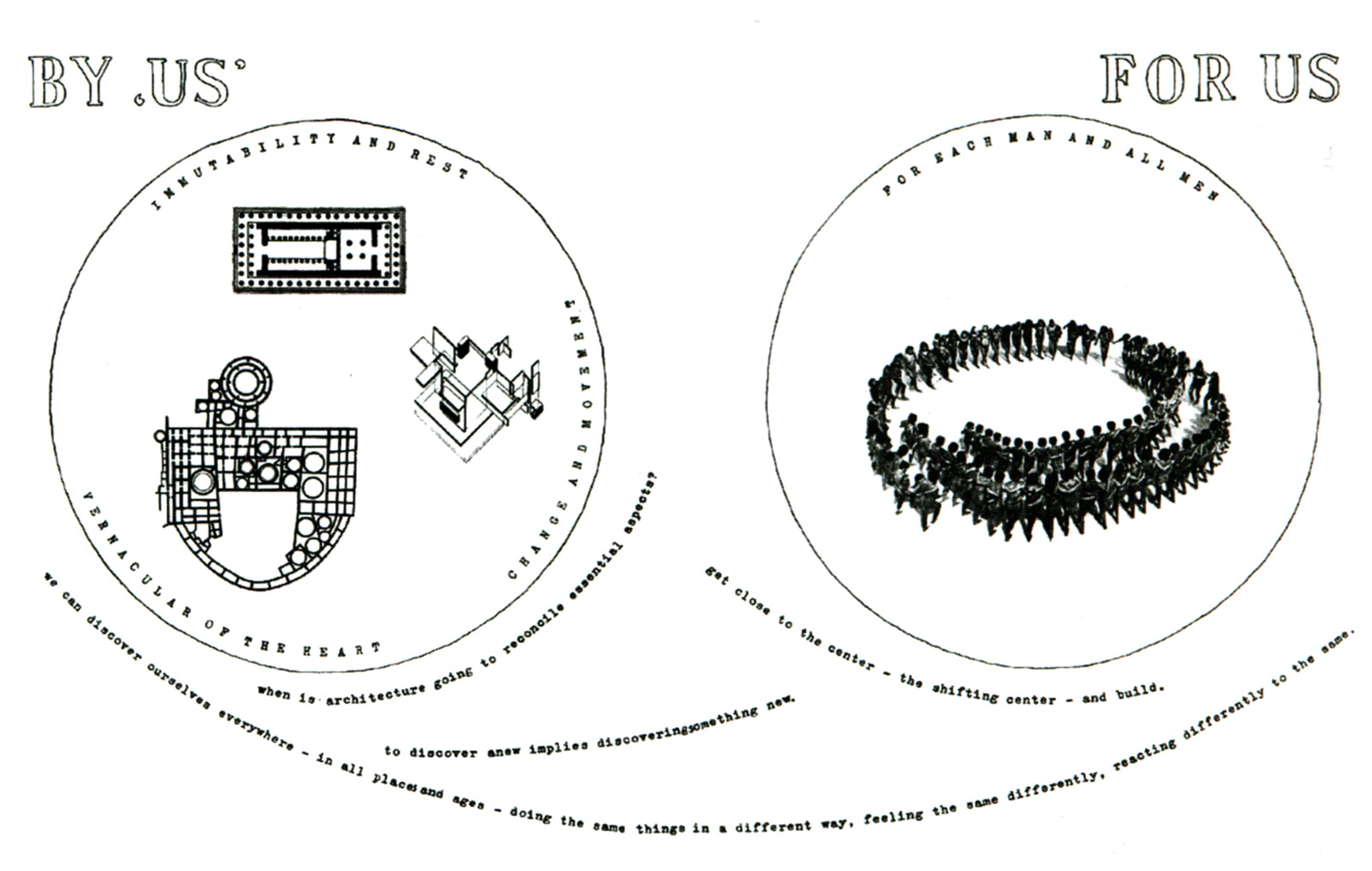

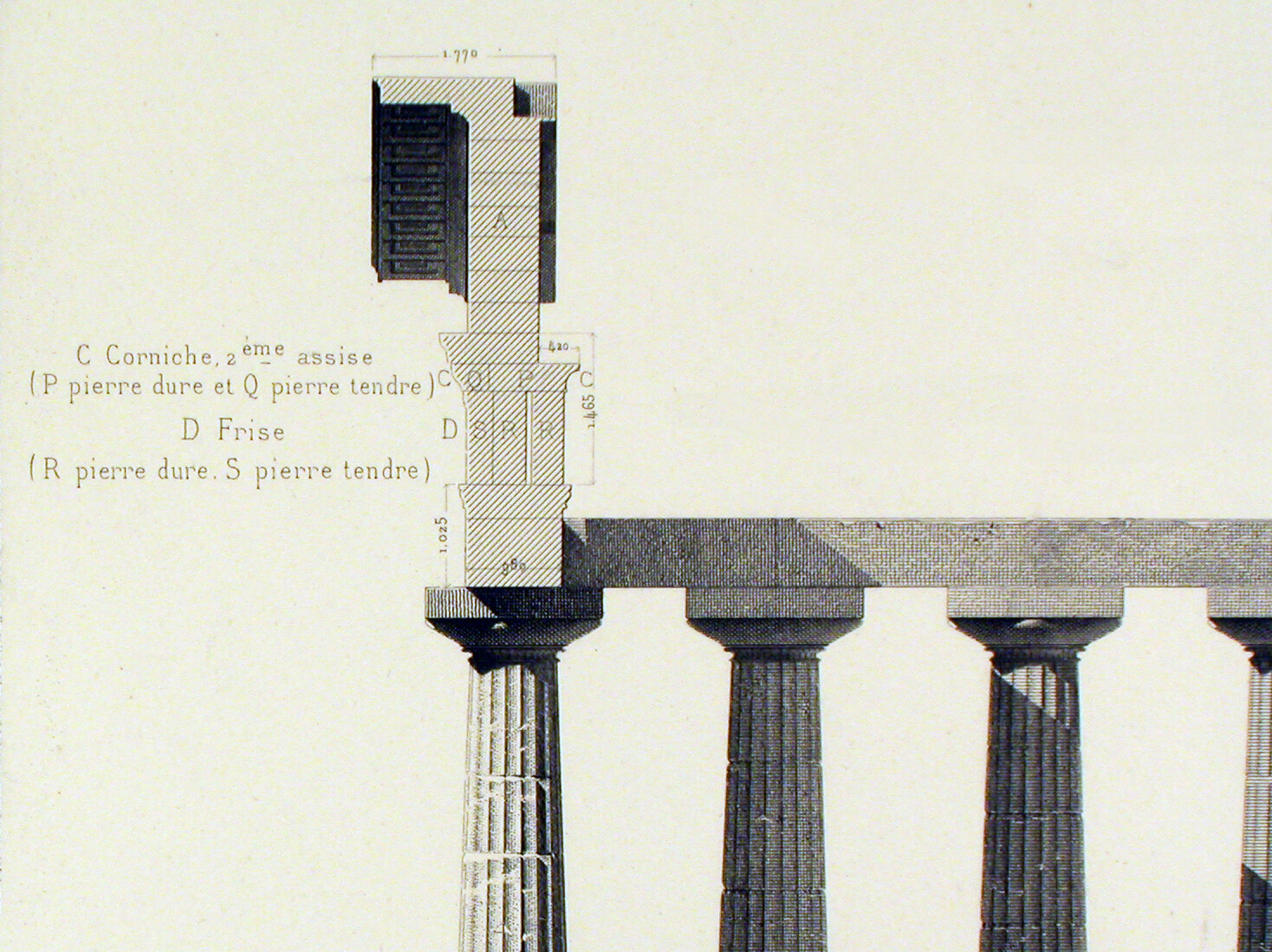

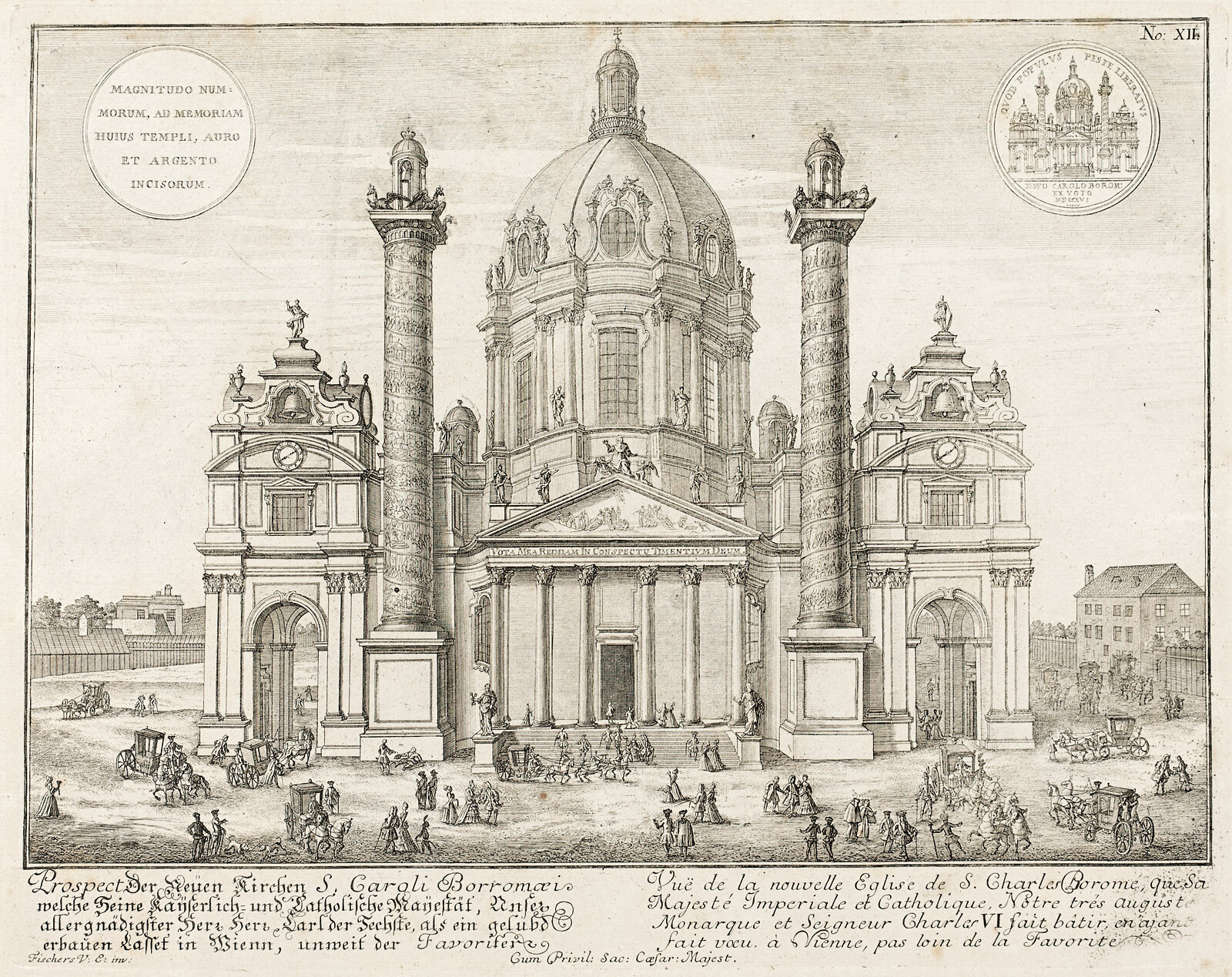

There are, of course, exceptions. Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction stands out as a book that found a way to deploy the architectural history survey to creative ends.1 His “gentle manifesto,” published in 1966, uses the matter of the survey—two dimensional images of historical buildings, mostly in the form of black and white photographs—and deprives (or liberates) them of chronology, context, and relative scale in order to facilitate their use in new ways. Venturi’s book was published in the same year as the first edition of Aldo Rossi’s L’architettura della città; two years later, Manfredo Tafuri’s Teorie e storia dell’architettura appeared in print.2 Unlike Venturi, Rossi was concerned with buildings as three-dimensional objects. Buildings were the fabric of the city, both shaped by and shapers of their contexts, repositories of cultural memory and members of a genealogy of building types. Tafuri’s Teorie e storia dell’architettura, on the other hand, was a book that endowed the study of historical forms as well as the historical enterprise itself with a new critical power. Tafuri, Rossi, and Venturi all demonstrated that historical architecture could provide the material out of which a vigorous architectural theory could grow. Furthermore, as practicing architects, Rossi and Venturi—however different in method and argument—both sought to render the richness of historical forms into a wellspring for architects: history was allowed once more to occupy a vital place in the design process.

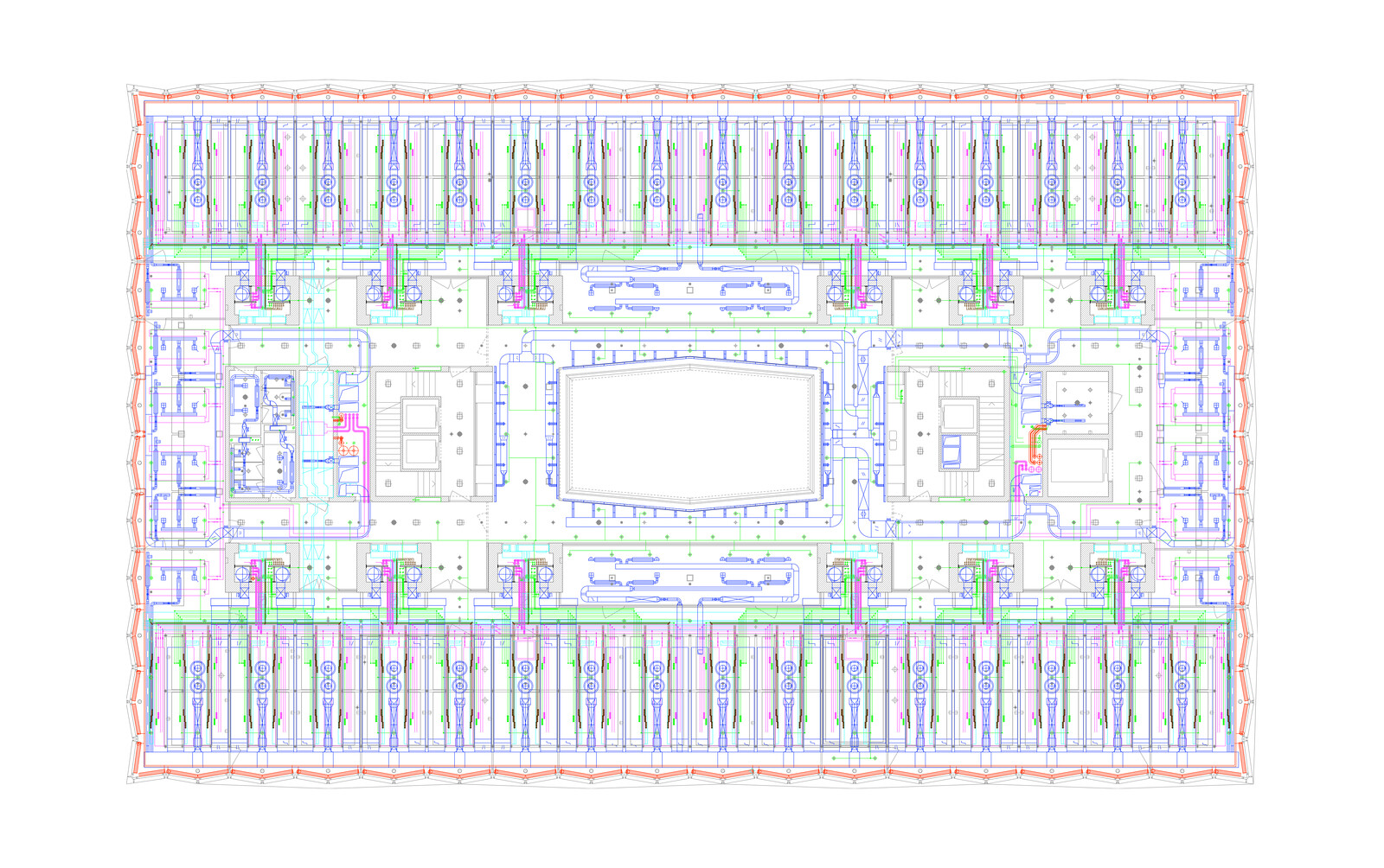

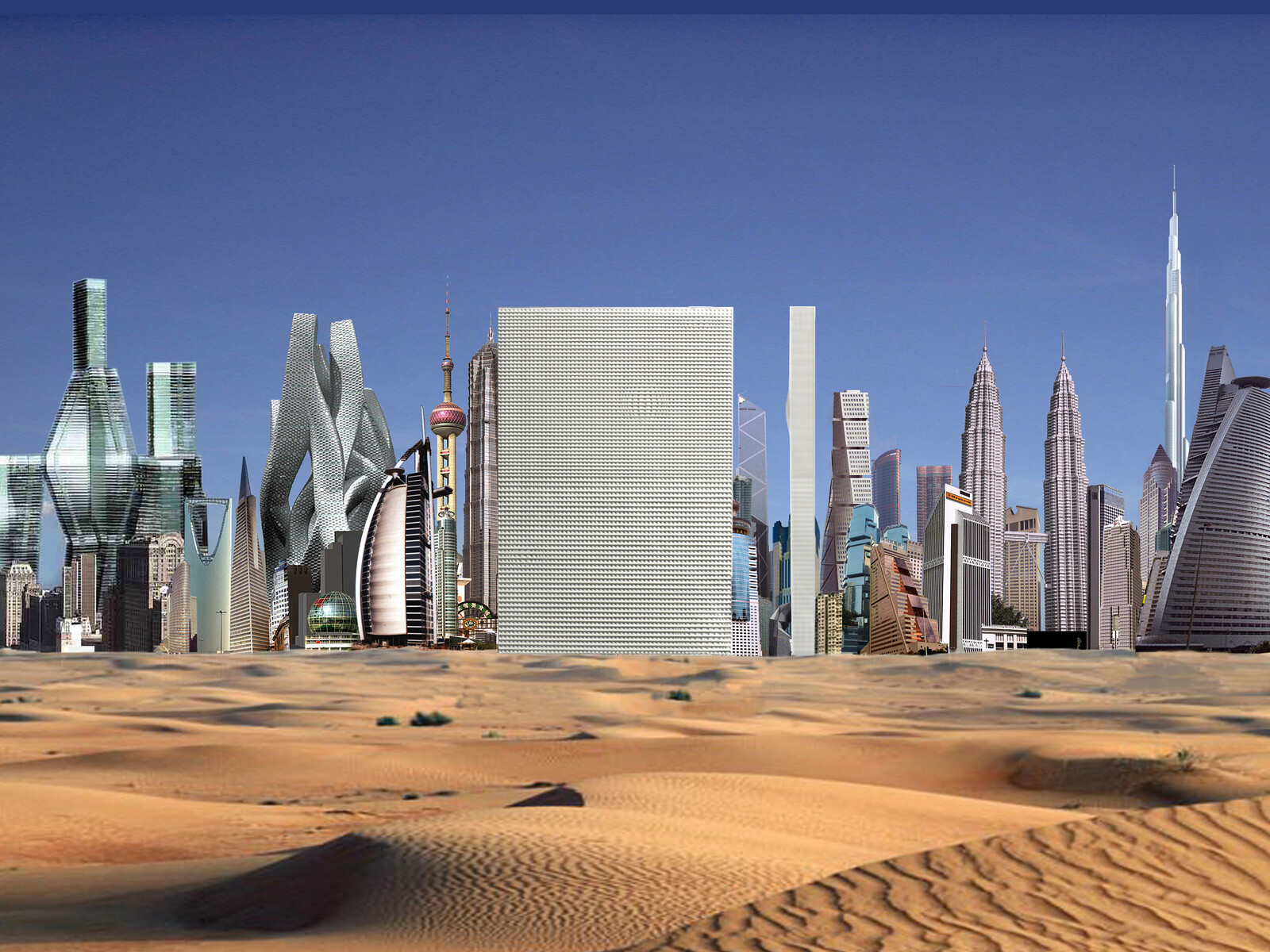

Fifty years later, however, history’s role and prospects are much less clear. The rise of new digital technologies and fabrication techniques has enabled architects to design and produce forms that seem to have no connection to anything built in the past. If history can no longer furnish precedents, types, or fragments to draw from and reuse, then what is its use to architecture? Yet for Venturi, Rossi, and Tafuri alike, history was far more than a repository of dead forms. History was a resource that allowed them actively to think through the discipline of architecture afresh.

It is our most pressing task, as historians and educators and individuals involved in the design professions, to position history as integral to the creative process. By combating the stereotype of history as something concerned narrowly with an ossified set of precedents and models, we have the chance to refashion architectural history into a vehicle for the field’s most innovative thoughts and aspirations. To do this, history must be understood as a form of architectural thinking. History can provide us with a vehicle to think about architecture in all of its forms—as theory, as representation, as process, as video game, as experience, as utopia, as ruin, as network, or as a cloud. Thinking, reading, debating, and writing are exploratory processes just like sketching and modeling that help us to think, allow us to question, and enable us to push our ideas further.

History necessarily holds a mirror up to the present, revealing both continuities and differences. Studying history reminds us that whereas some questions hold their ability to stimulate thinking over different time periods or across cultures, others are temporally and culturally distinct. When we look at the history of the more recent past we can easily follow the development of ideas and attitudes that are still vital today. Assumptions that a relationship exists between new materials and formal innovation, for example, or between the presence of parks and a city’s quality of life, have very clear historical trajectories that can be traced between the nineteenth century and the present.

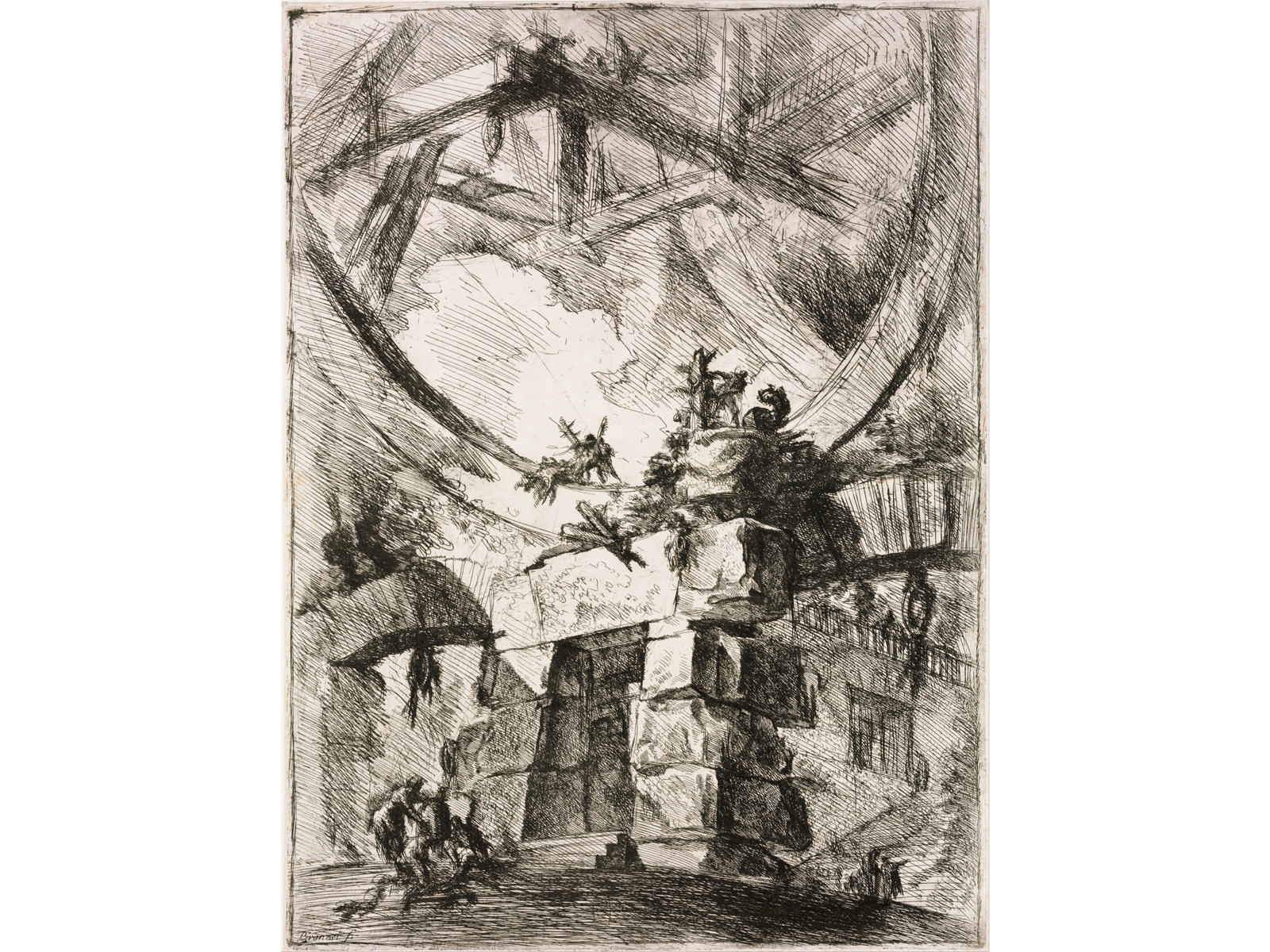

When we consider the more remote past, however, differences—rather than continuities—in patterns of thinking and doing become more apparent. Looking at earlier periods causes us to stumble upon ways of thinking that strike us as completely alien, and it is precisely this strangeness of the past that harbors the greatest potential. When we study things or habits of mind whose continuities with the present are apparent, history affirms what we already think we know. When, on the other hand, we confront things that are unfamiliar and remote, history can undermine our certainties and spur us to think through everything anew.

Can the study of distant times and cultures constitute a radical act? It may be useful here to recall that the word “radical” derives from the Latin radix- or “root.” In its medieval incarnations the term implied going to the origin—and therefore the essence—of something. When “radical” began to be used in a political sense toward the turn of the nineteenth century, such as in the term “radical reform,” it retained the connotation of a process whose ability to effect change was dependent on its far-reaching nature and determination to penetrate to the very foundation of a political system.3 History is thus by definition a radical practice, and I would argue that the further it strays from a familiar present, the more radical it becomes. When we seek to analyze large swaths of time, or bridge the gap between a remote age and our own, we are forced out of our zones of intellectual comfort, encouraged to imagine other modes of thinking, being, feeling, and acting, and led to ask the most far-reaching of questions. When framed in this way as a radical form of thought, history can fulfill its potential to be a powerful engine of change.

Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966).

Aldo Rossi, L’architettura della città (Venezia: Marsilio Editori, 1966), English edition, The Architecture of the City, translated by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982); Manfredo Tafuri, Teorie e storia dell’architettura (Roma e Bari: Laterza, 1968), English edition, Theories and History of Architecture, translated by Giorgio Verrecchia (London: Granada, 1980).

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and e-flux Architecture.

Category

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zurich and e-flux Architecture.