Nick Axel How did the project of unMonastery come about?

Ben Vickers In 2011, I was working for the Council of Europe doing social network analysis for a project called EdgeRyders, which was a part of the Council’s early warning division. We were building a crowdsourced think tank which identified fringe groups throughout Europe and brought them together onto one platform. The initial research culminated by inviting the most active participants of the platform—from the likes of Telecomix, WikiLeaks, the Pirate Party, strange squats, think tanks, etc.—for a three-day conference at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg to discuss the challenges Europe would be facing in the future.

NA What were those challenges? And what was informing the way the group decided to address them?

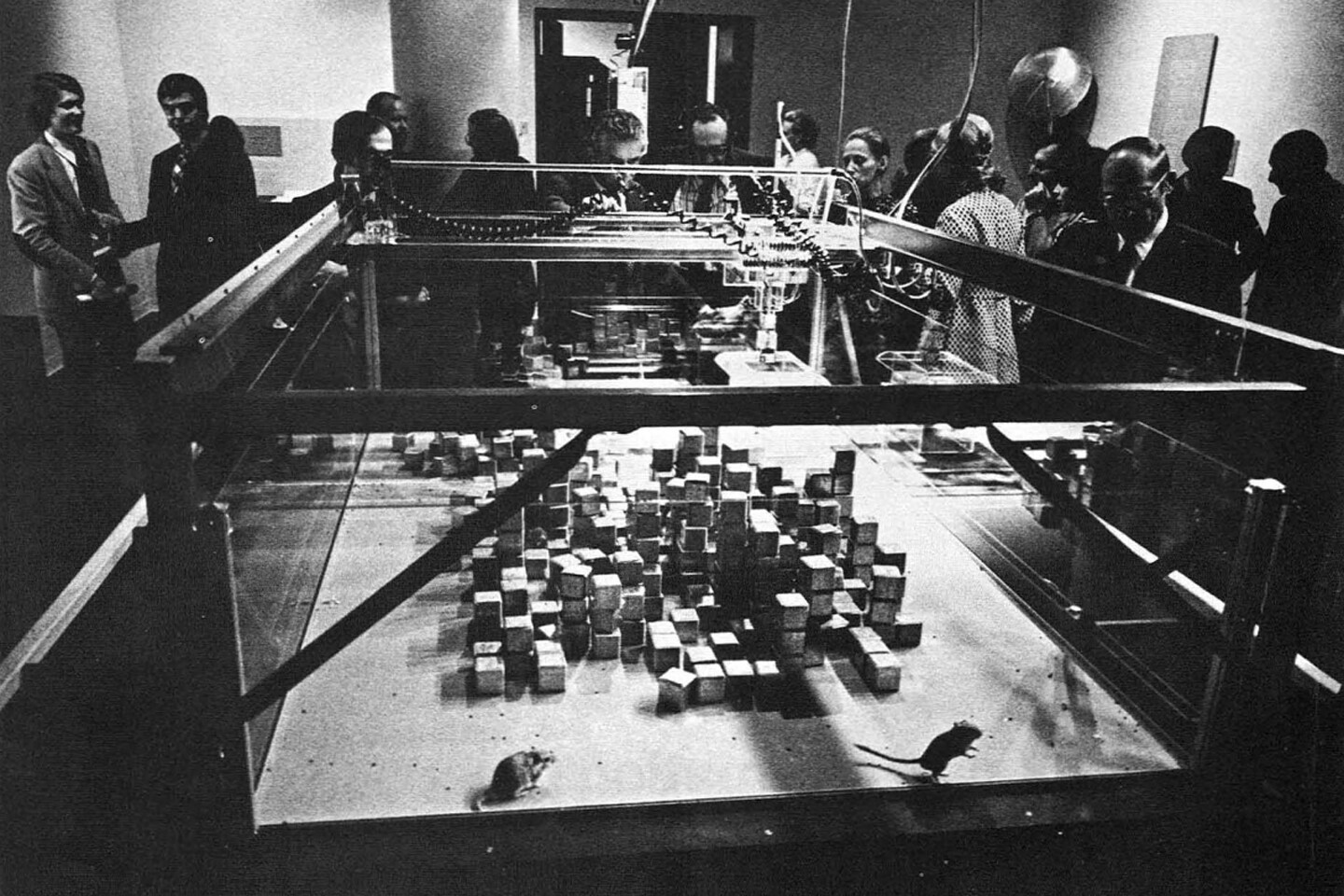

BV This was all back in 2012, which as a historical moment, felt very different than today. It was a strange moment. People talked about a divided Europe, but it seemed ridiculous to many. Somebody at the conference held up a bitcoin and nobody knew what it was. Simultaneously, you had the emergence of the Indignados and Occupy movements; hackerspaces were starting to come into maturity as a network; and Enric Duran had just stolen a lot of money from banks around Europe to set up a place outside of Barcelona that described itself as a post-capitalist, eco-industrial colony. In this milieu, unMonastery emerged as an idea within a group discussion of around thirty people attending the conference. Within the policy context we found ourselves in, we initially framed the initiative to address three prevalent issues that we felt were pragmatic for reshaping the imminent future of Europe: the large number of empty and disused properties throughout the continent; the effects of austerity and the rollback of state service provisions; and high levels of unemployment, particularly among young and highly skilled individuals. The idea was to invite young people into empty properties to bring them back into use and to work in collaboration with the local community in order to provide relevant services for that specific area.

NA How did you end up realizing it? And what were the results?

BV Thanks to our connection with Alberto Cottica, one of the founders of EdgeRyders, we were given the opportunity to run a six-month prototype of unMonastery in an abandoned monastery in the city of Matera, in southern Italy, as part of the run-up to the city’s bid for the 2019 European Capital of Culture (ECC). The total running costs of the Matera experiment was €33,000, which if you think about all we were able to achieve, is quite impressive. Fourteen people lived together for six months. We produced approximately thirty events, including large-scale hackathons; we set up a programming framework for kids and an open tech school; we mapped the city’s transit system and uploaded it to OpenStreetMap; we attempted to prototype open-source wind energy project; we developed an online platform that served as a mirror back onto the local area, sharing what residents thought; we attempted, but ultimately failed to build a WiFi mesh network across the Sassi, the most ancient parts of the city; and we effectively served as a quasi-think tank for the city‘s winning ECC bid.

NA It sounds like it was quite a success!

BV It sounds like that, and it felt like that in many ways at the time. We set out to create a spectacle for a new kind of imaginary about how you could produce a space like this. And looking back, I think we achieved that. However, progress on the overall ambitions of the initiative to establish a large-scale network, and for our results to be replicated by others, has been limited.

NA What’s the relation between unMonastery and monasteries, aside from the fact that it started out in one?

BV At the unconference that followed the Council of Europe conference, a session was convened that focused on how to build a networked, physical infrastructure that can support this online, crowdsourced think tank of misfits and digital nomads. At the beginning of that conversation, somebody suggested that if we were to build such a thing, we should look to the monastery as a metaphor for talking through how we would conceive and do it. As a historical typology, the monastery addressed a lot of the issues we were concerned with and questions we were asking ourselves at the time, like: How to build an institution that can support a networked approach? How to conceive of a multigenerational project? How can a decentralized network interact with existing power without undermining itself? How can the tacit knowledge of that network be preserved? Is it possible to create a structured and replicable framework for living in the world that individuals can use as an anchor in times of extreme instability? Is it possible to produce an attractive way of life which is frugal and meets current planetary resource constraints, but one that is also joyous, ecstatic, and rewarding? Why do monasteries succeed but secular communes fail? What are the technologies that we can do without?

NA Are those questions still relevant today?

BV I think they are still relevant questions to be undertaken, but I don‘t know if it‘s relevant for unMonastery to take them on. After our first prototype in Matera, unMonastery was set up in Greece during the moment Syriza came into power on the assumption that, if there was going to be a turn to the left in Europe, it was going to come from the south. Another, more specific reason we set up in Greece was that we believed the refugee situation Greece was—and still is—experiencing was going to become decisive for the future of Europe. In the solution-led ethos of the project, it made sense to try and apply open-source technologies and decentralized hardwares to the Greek situation. But what we found was that those technologies and those processes were not robust enough to be able to deal with the situation that Greece faced, and indeed, continues to face. There was a coming of age in terms of understanding what those issues are. I should also state that, having run three separate large-scale unMonastery experiments, the shrinking patchwork network that composes unMonastery today is not exactly in agreement as to how the initiative might move forward in the future. Forks and schisms are likely more necessary now than they have been at any time during our six-year history.

NA At around the time when unMonastery emerged, the English translation of Giorgio Agamben‘s Highest Poverty was published.1 Within that book Agamben identifies the relationship between the practice of a rule and the architecture of a space. How were rules practiced within unMonastery? And what was the relationship these had to the spaces that they took place within?

BV I have to preface this by saying that the entire endeavor was taken on with a kind of jubilant naivety. This is quite important, because were it not to be undertaken in that way, it wouldn‘t have been so bold; it wouldn‘t have attempted to remake and rethink a way of living in the world. There was a base awareness that those who had participated in a utopian optimism around technology were beginning to change their position. We weren‘t necessarily pessimistic about technology, but there was a deep awareness that, as a result of emerging technologies such as blockchain and augmented reality, a trajectory where rules would increasingly dominate was to become more and more present within our everyday lives. That is to say, the feeling of freedom produced by early experiments in cyberspace and the assumed move towards decentralization, and thereby greater autonomy, was already beginning to wane in the face of increased state surveillance and the concentration of power on the part of the “big five.”2 All of this is obvious to see today in the events that have since come to pass, but it wasn’t at the time. Intuiting this potential trajectory, we attempted to produce a way of thinking through and living with those technologies upstream, before they were cemented within the everyday apparatus of civilization, and to produce a different outcome than one in which defined is defined by greater centralized control. The reason why Agamben‘s thinking is important because he identifies a revolutionary potential within the monastic rule as the last time within Western thought that there was a form of life, a bios, where the rule and life coexisted as one and produced one another.

NA Were you aware of that revolutionary potential when unMonastery was started?

BV No, not exactly. Much of the important thinking that emerged from unMonastery came through practice, mistakes, and digestion. At the outset, we produced a kind of caricature of what a monastery is. It was through the process of doing unMonastery that we realized the profundity of forms of life and what is produced in the monastic rule. Not everybody involved in unMonastery dug deeper into that, but those of us who have, have had to radically alter their lives. My base conclusion from this, at least, is that technology, tools, and infrastructure cannot change current conditions by itself, regardless of the intention with which its making is imbued.3 It is instead necessary and vital to change oneself, to transform one’s mind.

NA Was the starting point of unMonastery to see technology itself as a rule, or as a set of rules? Was the question not how do we live according to a monastic rule, but how do we live according to a technological rule?

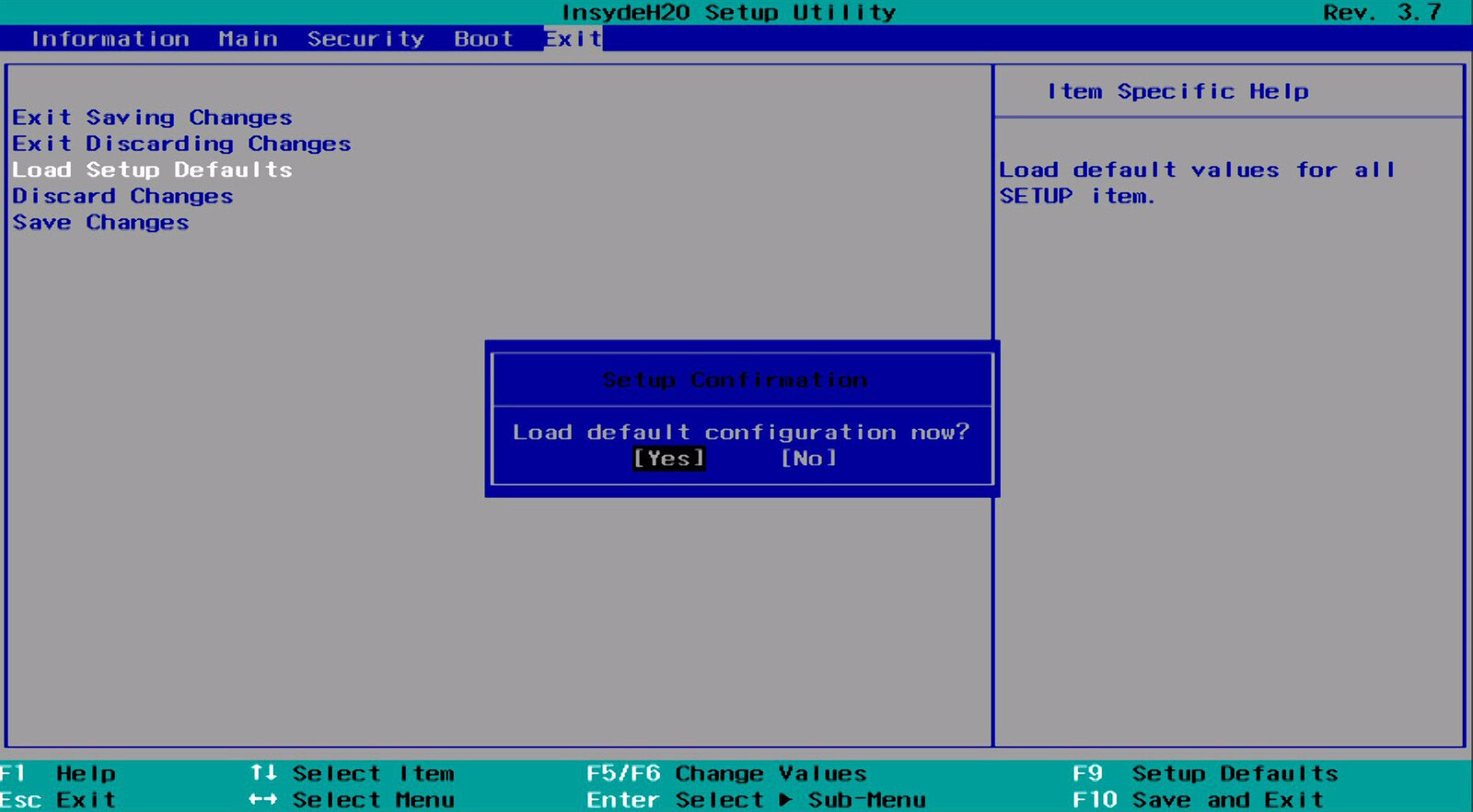

BV Partially. But it was also a question of how to have fun with technology. We were drawing from hackerspaces and the rulesets that are used as templates for shaping those spaces, which were themselves largely derived from the cybernetic theories of the architect Christopher Alexander. Alexander had this idea of design patterns, of documenting problems and designing nonspecific solutions that were transferable. This informed programming languages, which then informed hackerspaces, which then led to the rise of a network of decentralized spaces as articulated by programmers. We were working to find a way to merge cybernetic thought, technology, and spatial considerations. But we were also, in a very basic way, asking the question of what it would be like to produce a hacker space that people live in, or a commune appropriate for our technological age.

NA Even though this might not have been the starting point, Agamben has a very elegant passage where he claims that Franciscan monks could understand what they were supposed to do just by looking at certain things in their immediate environment; by registering their body in space.4 How was the architecture of these spaces, where unMonastery took place, considered? How did you relate to it?

BV The reason why we wanted to do the first prototype in Matera was that it was an ancient city. The city was essentially established by troglodytes. It is a place borne of asceticism: it‘s dug out of the hillside, and there are monasteries everywhere. It was the right setting in which to try and create this imaginary, to will its making into the world. In lots of ways, it was just roleplay. But to your question, the way in which we were trying to produce a life was through the architecture of the way we lived, not necessarily the environment itself. Like a monastery, we had a daily routine.

NA Did that change when the project moved to Athens, and the ideal scenography was no longer there?

BV unMonastery moved to Athens at the beginning of 2015, when there were lots of vacant properties due to the speed at which the city that was built. So instead of a centralized approach, as we had in Matera, with everyone living in one single space, in Athens, we were spread across the city, in different apartments. We found that the city itself affected the project; not just because of what was happening in that political moment, but because of the fact that Athens, like any large city, has its own temporality, its own rhythms. Perhaps this was intensified because of the project’s decentralized form, but we learned from Athens that you cannot produce the type of space we were attempting to do inside a city.

NA Why not?

BV The monastery is contingent upon its ability to control time. Time emerges from monasteries as an attempt to keep the rhythm of the office and prayer. Over time, we learned various things about doing this type of experiment in different types of environments. Where things stand right now, at least from my own perspective, is that there is a requirement to be able to articulate the architecture of the project, or at least both its location and construction. That said, I think there needs to be a massive experimentation in terms of what type of spatial settings unMonasteries can take place in, be it the countryside, a mid-size city, or a metropolis; both centralized and decentralized. We started in the context of a mid-sized city which was experiencing a massive brain drain at that time. That space of a problem afforded an opportunity, and also a set of conditions where it’s successful replication might be more likely.

NA There‘s a certain tension between the fact that unMonastery tries to track, anticipate, and respond to a current political situation, and that monasteries themselves are multigenerational infrastructures, with, as you found, an average lifespan of 473 years. Can you reconcile these two divergent characteristics of the project?

BV unMonastery ran for about a year before any of us actually went and visited a monastery. And when we did, particularly for myself, it was a deeply humbling experience. It allowed me to recognize a cognitive dissonance between what we tried to articulate together as a group and what its model actually was. I can tell you a nice, well-contained narrative about unMonastery and I can describe it in terms of being an elegant solution, but there is something dishonest in that telling. It’s this approach or ability to narrate the project that became shattered, at least existentially, with my encounter with monasteries. So in terms of your question of how to deal with those contradictions, I don‘t know. I honestly don‘t know, but I‘m now prepared to say that. I previously wouldn‘t have felt comfortable with acknowledging that unknowing. The question that remains is, through accepting that unknowing, will I or others be capable of taking the necessary next steps to work through it and produce something that is of value to others?

NA This unknowing seems to be most often met by one of two knee-jerk reactions. One is to abandon the question altogether and revert to familiar systems of knowledge. The other is to follow or practice a rule, which may not tell you exactly where you are going, but gives you the space and allows you to think about potential answers. You yourself have experimented with following the Benedictine rule. Can you speak to that personal experience, the psychological, the physiological experience of what it‘s like to follow another rule, to practice another form of life?

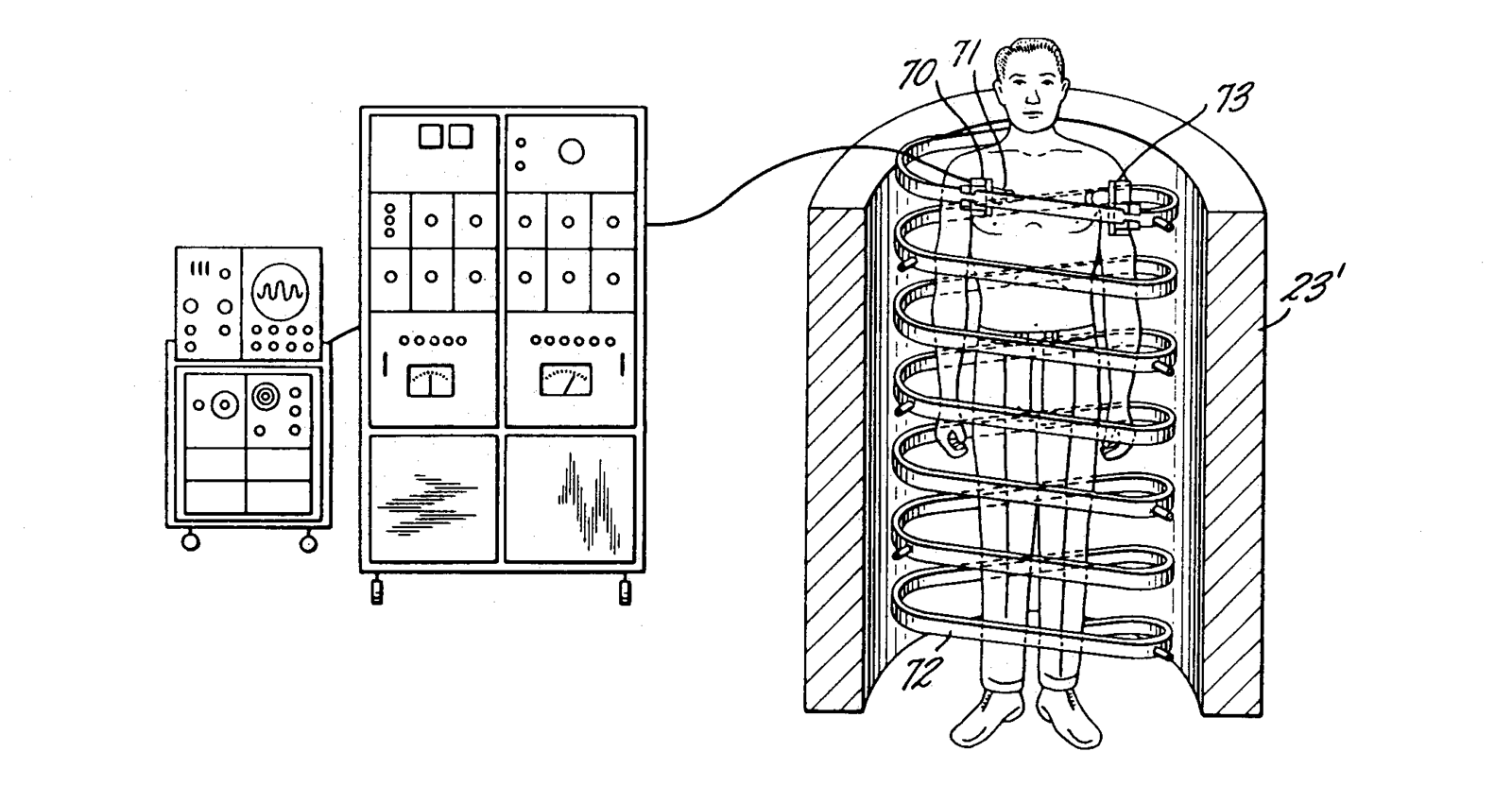

BV There‘s this idea that the rule produces itself through the very living of the rule.5 So the rule is not something external from the self. Because it maintains your sleeping rhythm, your rhythm of activity, your metabolism, and the material that you ingest, it has a profound effect on your perception of reality. That change can come very quickly, from just a few days, but the issue is that it only works in isolation. In order to practice something like the Benedictine rule, you have to live in this kind of hermetically sealed bubble, which is a problem if you want to exist within society.

NA Is it an all-or-nothing proposition though?

BV Exactly, it can’t be. So the question then becomes: if I accept the fact that exit is not an option, and that I‘m going to continue to exist in society, how will I transform my everyday life? That this work produces a set of practices that can be shared, but that are only innately valuable for oneself is, in many ways, and for many people, obvious. It‘s perhaps only relevant for a particular group of people. But I feel that there is a more general, desperate hunger today for some kind of surrogate structure that can be brought into one‘s individual life to provide stability. I truly believe that daily practice is a path worth following and seeing through, but the issue is that it‘s very slow and requires quite an intense level of experimentation that cannot be accelerated through time by just having more people do it, as “consciousness hackers” might have you believe. In that sense, you inevitably become aware of the need for a multigenerational project, and you begin to comprehend what that might begin to look like.

NA I’ve heard so many people say that “we are creatures of habit,” but I don’t know if I believe that. Or at least, I don’t know if that’s true today. There’s so much disrupting our habits today, and we’re very used picking up habits from others or from other things. So this importance that you give that can only really be given to oneself, in determining one’s own life and one’s own practices, is daunting, but also hugely inspiring. In the way that unMonastery has published a kit of parts or toolkit, I do hope that a public discussion can emerge about practices for a more autonomous form of life.

BV I’m massively excited about that. The thing that I find inspiring and intriguing at the moment is that right now, there’s a red thread emerging; there’s an emergence right now of all of these different monastic-related initiatives. And there is something that I call the “ascetic continuum,” which speaks to the fact that ascetic practices have been present across cultures and throughout human history. This all suggests to me a certain inevitability for this form of living and institution. Monasticism has shown itself to be a dormant technology awaiting the right conditions to thrive and grow again, and I think that time is close. I think the problem of unMonastery was that it had been platformed too much. It was a spectacle. It was an attempt to produce a spectacle that created the necessary illusion that something else was possible in order to ensure that something else was possible. And now it needs to recede and become competent in its tools and its expression. And then it can reemerge, which is also the story of monasticism… It recedes at different times and it flourishes in others.

Giorgio Agamben, The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life, trans. Adam Kotsko (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013).

The “big five” is a name used to describe the five primary multinational technology companies in the West: Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook.

See Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

Agamben, “Rule and Life,” in The Highest Poverty.

Giorgio Agamben, “Towards an Ontology of Style,” e-flux Journal 73 (May 2016), ➝.

Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program.