Nick Axel What brought you to this idea of building a 10,000-year clock?

Daniel Hillis I started thinking about it in the late 1980s, early 1990s. When I was a child, people always used to think about the year 2000. And when it got to be the 1990s, people were still just thinking about the year 2000. It was as if the future was shrinking, and I wanted to live in a longer future. I began working on the clock just for my own purposes, because I wanted an excuse to think longer term. Then as I spoke with my friends about it, they got interested and I realized that the clock was more broadly relevant. Lots of people wanted an excuse to think about the future in a different way. So eventually, Stewart Brand said that we should start a foundation to build it. With the Long Now Foundation we’ve built several models over the decades, and the clock is actually on its way to being finished inside a mountain in Texas.

NA What has it taken to build such a contraption?

DH I always imagined the clock as this experience of traveling through a desert, climbing up to the base up a mountain, finding a hole, going deep inside, and coming across a spiral staircase going up into it, where there would be a bunch of machinery. So I first had to find an empty mountain out in the desert that had the right kind of geology, which I was lucky enough to do. Once I did that, I had to bring in the equipment to make it. But there was no way to get to the mountain—there were no roads—so I had to build the roads. Eventually we started tunneling and blasting into the center of the mountain, and we serendipitously came across a natural cave right where the horizontal and vertical were meant to meet. We started on the vertical shaft by making a small hole with a drilling rig on the top of the mountain, and then pulled what’s called a raise drill up to create the twelve-foot hole. We then had to build a spiral staircase up through the shaft, so we designed a special robot with a diamond saw that could climb up the hole, and which over a few years has slowly climbed up about 500 feet into the mountain carving a staircase out of the shaft wall. Then we started to build the actual elements of the clock, which all have to be made of materials that can actually last 10,000 years, like high millennium stainless steel, titanium, and ceramics. All of the bearings are made without lubrication too. We’ve got about sixty tons of machinery inside the mountain so far, and it’s about half in.

Looking up the shaft at the Clock of the Long Now. Photo courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

Entry to the tunnel leading to the Clock of the Long Now. Photo courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

Construction site of the Clock of the Long Now. Photo courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

Looking up the shaft at the Clock of the Long Now. Photo courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

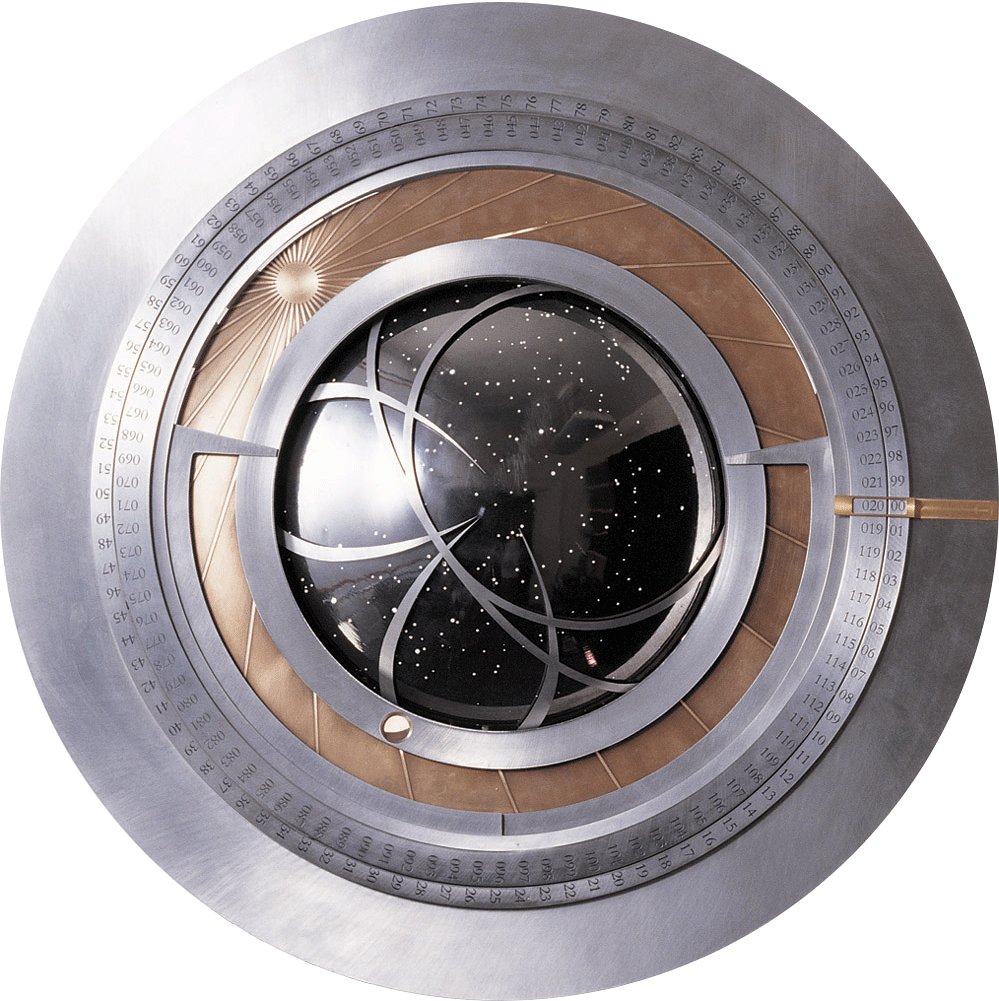

NA So how does it work?

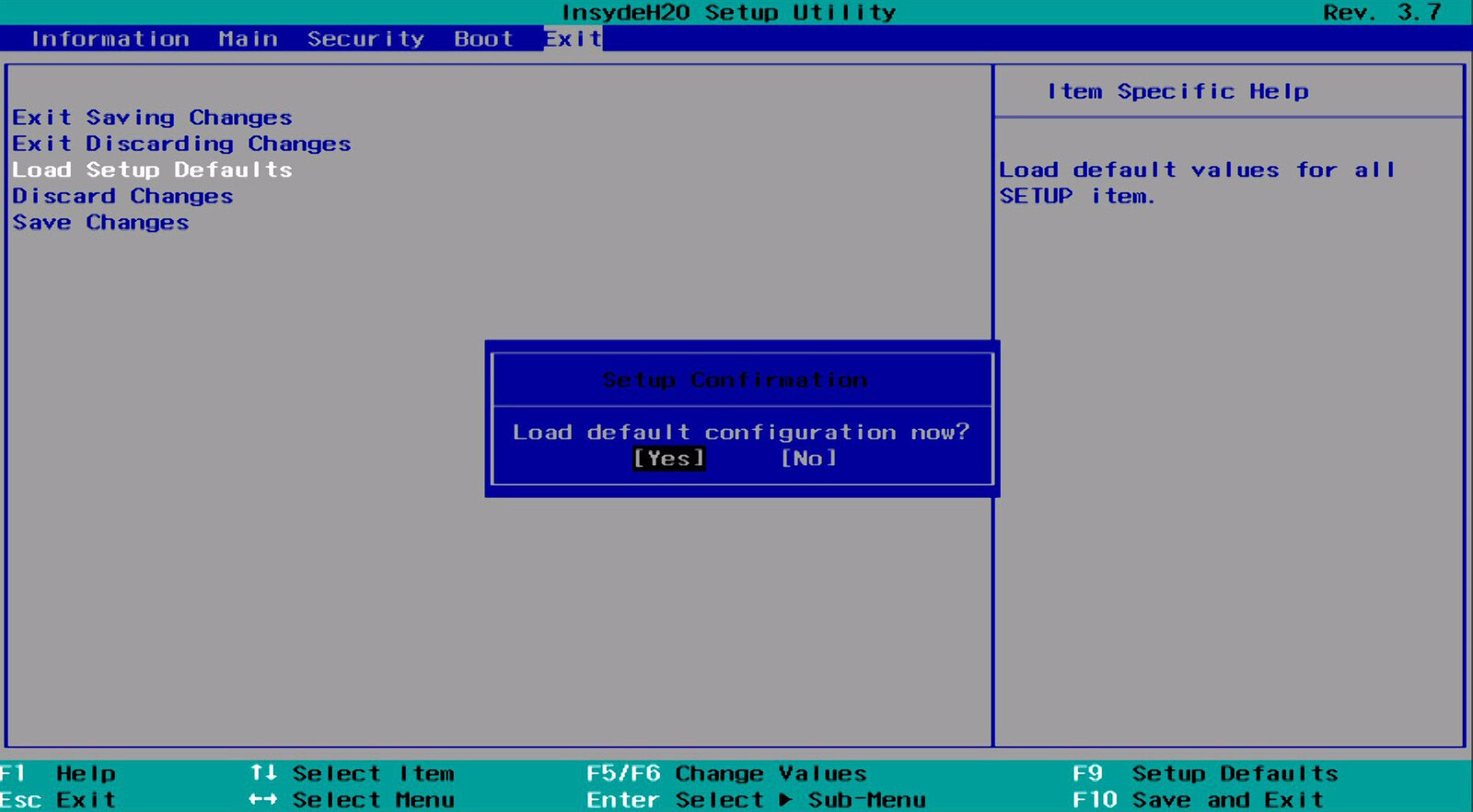

DH The clock is designed so that it not only keeps time but also powers itself. It harnesses the day-to-night temperature shift and the piezoelectricity of ground quartz. It synchronizes itself, too. On summer solstice, the sun shines straight down the shaft and warms a part of the clock up, so it can adjust itself to that moment and stay on time. And of course, you cannot display time on a 10,000-year clock in the normal way, with years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds, so it displays the position of the sun and the moon and the stars, which move around as the clock goes.

NA What do you imagine it would be like to visit the clock, once it’s built?

DH If you visit the clock, you have to make a pretty big commitment. It’s far away. It’s out in the desert. You have to climb a mountain. It’s designed so that along the way you feel like you might be lost, or that you’re in the wrong place. And then you finally get to a point where you’re at the bottom of a giant stairwell, with a tiny light up at the top, and as you climb up, you pass the machinery, and once you get to the top you can wind it. The clock rewards you for winding it by ringing a set of bells, and each time the bells ring differently.

NA Do you see the clock as a monument?

DH I would say it’s more like an anti-monument. It’s hidden away inside a mountain. It’s deliberately designed to be unphotographable; you have to be too close to it. You really have to go to it to see it. But the value of the clock is mostly in thinking about it. Civilization goes back 10,000 years, so this can help think about what the Earth will be like 10,000 years from now. I ultimately think stories are the things that last the longest. And to be a story, it has to have an element of mystery to it. The thing about monuments is that they tend to be very bounded by what they are. They’re very understandable. I mean, you look at a statute and you’ve seen it, that’s it. That was the opposite of what I was trying to do with the clock. I wanted to make it engage you and pull you into it; to make it something that you can never quite entirely get your mind around.

Diagram of the clock face, depicting the year, century, horizons, sun, moon, rete, and star field in rings moving from the outside in. Photo: Rolfe Horn, courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

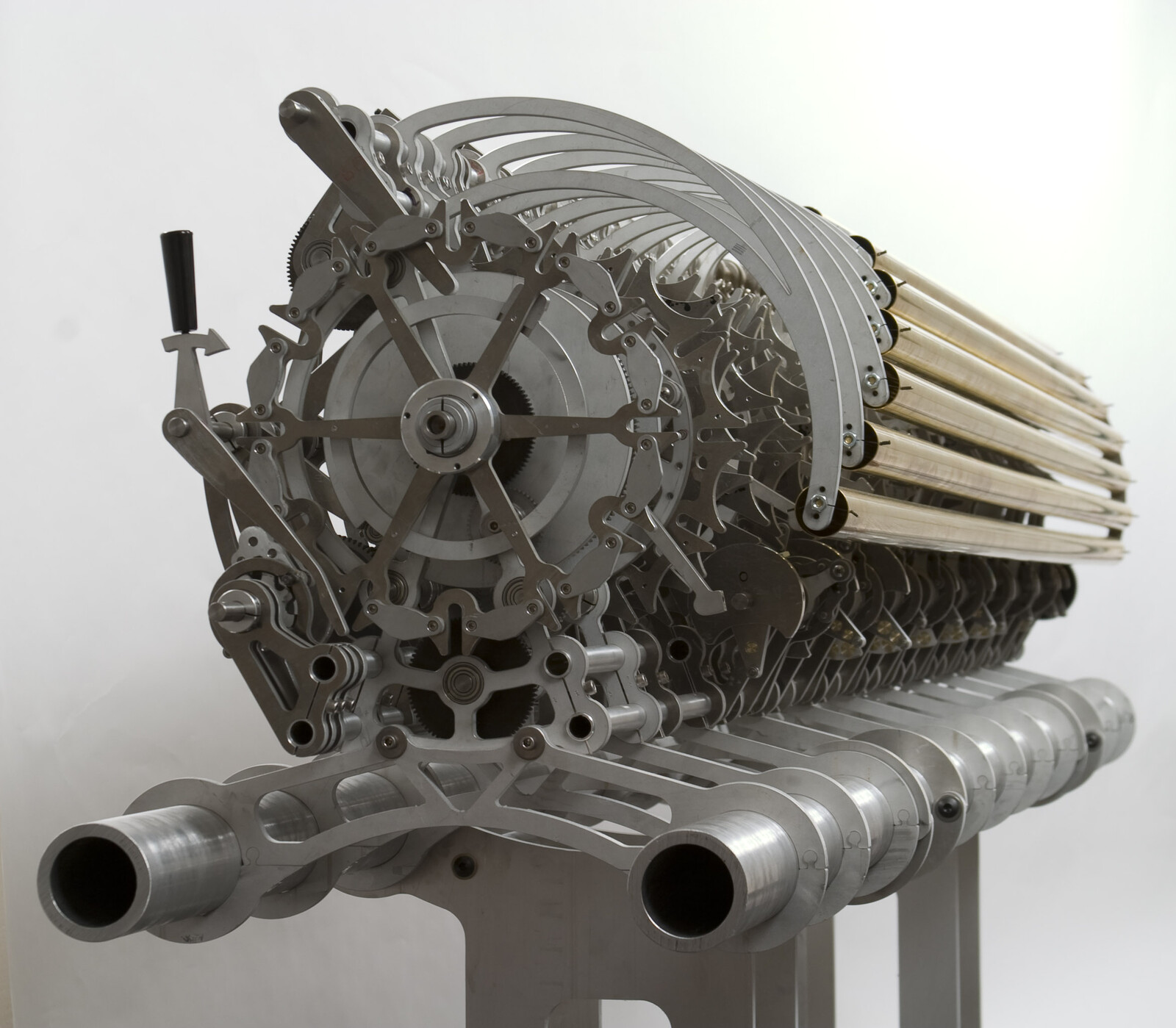

Chime generator. Photo courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

Detail of the clock’s adder. Photo: Rolfe Horn, courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

Diagram of the clock face, depicting the year, century, horizons, sun, moon, rete, and star field in rings moving from the outside in. Photo: Rolfe Horn, courtesy of The Long Now Foundation.

NA It’s interesting how the clock is not really designed to tell the time, but rather to record its passing. Can we understand it as a statement that says we have lost the ability to keep track of time?

DH Because of changes in technology we naturally experience a very short, immediate version of time. The point of the “long now” is to take that piece of time that we care about—now—and stretch it out. The clock helps me feel connected to a timescale that is more at the scale of civilization than an instant message.

NA Do you see this clock to have a democratizing function? Not everybody wants this “now” you speak of to continue. And so I’m wondering if this clock can serve as a space to collect different presents, different pasts, and different futures, and allow us to move towards of more just “now?”

DH That’s something that some people might do with it. The clock doesn’t really have an agenda. I’m not trying to get people to think in a certain way or about a certain thing. It’s trying to create an opportunity, a context in which people can think about a set of things that they don’t normally get a chance to think about.

NA It’s quite curious how you’re saying that this is something that can take us out of the immediate, yet a lot of people that are behind this project are pioneers of the immediate. So much of the world we live in is so accustomed to the immediate, to planned obsolescence, to the throwaway. So I’m very curious how this might inspire long-term thinking in other areas or in other fields.

DH It makes things concrete for people. Speaking personally, global warming was a very abstract issue for me until I started designing the clock. I had to account for the slowing of the earth and the melting of the icecaps, and incorporate this into the design of the clock. I now think completely differently about a radioactive waste disposal. If you start thinking on those timescales, what is radioactive waste today will actually end up being a very valuable resource for people in the future. So what we actually need to do is put nuclear waste in places where it’s kept safe, but is also accessible and can later be taken out and used.

NA How so?

DH Well their half-lives are on the order of 10,000 years. We’ve created these new forms of matter, which will become usable again over thousands of years. It is a dangerous resource, it needs to be protected, but I do believe that over the next thousands of years people will have uses for the elements of uranium with short half-lives. You start thinking of things differently, of things that seem impossible problems for today, like world hunger, or problems that are not going to be solved in two or three years, but will certainly be solved in two or three centuries.

NA You speak about this transition that the Western World is going through now, from Enlightenment to Entanglement, where the historical distinctions between the natural and the technological—where the former is evolved, grown, autonomous, and mysterious, and the latter is designed, manufactured, controlled, and understood—become not just blurred, but inverted. When it comes to materials and to architecture, you have these fantastic ideas of growing cities using biological materials; designing them, engineering them in particular ways to create radically new types of structures, networks, and regions. How soon do you think we might see the entanglement materialize in buildings, in our cities?

DH I think we’re already beginning to see the beginnings of this kind of entanglement. You can find examples of buildings that use biologically-inspired forms or generative design methods. These types of things would have literally been impossible to design a couple of decades ago. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. You can think of some precursors to this like Art Nouveau, whose works were actually very difficult to make with the technologies at the time. You had to struggle with the technology in order to make it do what you want. Wood doesn’t naturally go into the shape that Gaudi wanted it to go into, but there are now technologies that produce that kind of aesthetic.

NA What do you think will bring urban entanglement about?

DH I suspect that its initial drivers will be aesthetic; that people will do it just for the beauty of it. But then there is also a practicality to the use of fractal structures or biosynthetic materials. I think we’ll ultimately find that it’s a practical way of building things; growing things in a controlled way instead of manufacturing. People are already beginning to plant landscapes that become integral parts of buildings. I think in a century from now, architecture will be unrecognizable because we will have developed the ability to engineer nature, to evolve technology.

NA With this idea of growing foundations or growing structures, some plants grow very fast, but some also grow very slow. Will this entangled materiality of the city be compatible with the culture of immediacy today, which in the form of real estate, is the current driver of our cities’ developments?

DH Well, first of all, we will invent new life forms, so we won’t be stuck with the growth rates of plants today. Plants construct their own solar cells to collect energy from the sun, so we could imagine plants being fed energy from an external power source to grow faster, or developing root networks in areas outside of the city that spread into it. This all sounds sort of fantastic, but if you’d think that we were having this conversation a hundred years ago and I started talking about electronics and computing, it would also sound fantastic, if not impossible. I think there’s no fundamental reason it can’t be done, and we’re beginning to gain the ability to manipulate the things to do it. Buildings will have nervous systems, they’ll respond, they’ll grow, they’ll adapt,

NA They’ll be far smarter than the nervous systems they have today. I mean, these primitive technologies of windows, doors…

DH Absolutely. And those things are all pasted on; they’re not really a part of the building. You can take them off and you still have the building. They’re not organically part of it in the sense that our nervous systems are a part of us. I can easily imagine buildings that bend toward the sun at the right time of the day. But it’s fundamental that these things be built into the building, rather than being some separate external controller that pushes it around, like a machine.

NA I imagine that if you have a grown house, you might want it to stop growing at a certain point, and then start it up again at a later date, in the way you can add onto buildings with the arrival of new family members. With gene editing technologies like CRISPR, we have the ability to engineer death, or the end of growth of certain things, of certain ideas, of certain practices at a profound scale. What do you think it would take to begin having these types of conversations within society, not just about where we should be going, but in more serious terms than the ones taking place today, what we should leave behind?

DH Realistically, I don’t think that’s the way change happens. I mean, it’s a nice idea that society would get together and have a conversation as to what to leave behind. I’ve been there, in those discussions, but change tends to happen in a distributed way, and very unevenly. Somebody learns how to use the technology, they learn how do something, it works, it fails… People learn from each other. It’s very messy. People always ask whether they’re doing something good or bad, but they’re always getting the answers wrong.

NA What can we do then? Just keep our heads down and move forward, waiting for something to bump into us and knock us out of our waking slumber?

DH Recognizing the possibilities puts us in a better position to see whether we are moving in a direction we want to. I do think that this type of technology is fundamentally empowering though. It opens up creativity. That’s the difference, in my opinion, between good technologies and bad technologies. I think that the best technologies empower lots of people to do lots of different things with them. So, agriculture, that’s a pretty great technology. It has kept billions of people from going hungry and it’s going on in all kinds of different directions. Of course we’ve already changed nature, and not always for the better. We’ve just done it by a very slow process that’s taken thousands of years. If we could just do that in a much more quick and deliberate way, it could solve a lot of problems, but of course will also create some new ones. So, we need to do it thoughtfully, and with some humility about our own ability to predict.

Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program.