Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program, featuring conversations with its Digital X Academic Body: Amber Case, Danny Hillis, Mary Lou Jepsen, Hasier Larrea, David Moinina Sengeh, Nicholas Negroponte, and Ben Vickers.

When Cedric Price declared “technology is the answer, but what was the question?” he could not have understood the extent to which such a logic would underpin the economic and industrial logics of disruption that have since become increasingly determining of social life and urban experience. Indeed, his statement was made over ten years before Shenzhen, what is today the metropolitan heart of the world’s trillion-dollar consumer electronics manufacturing infrastructure, even became a city. Price not only subordinated the question of form to that of function, as Louis Sullivan did at the cusp of modernity more than half a century prior. Rather, he opened up the very idea of function to that of engineering and design, and in so doing destabilized the relevance and legitimacy of all extant forms.

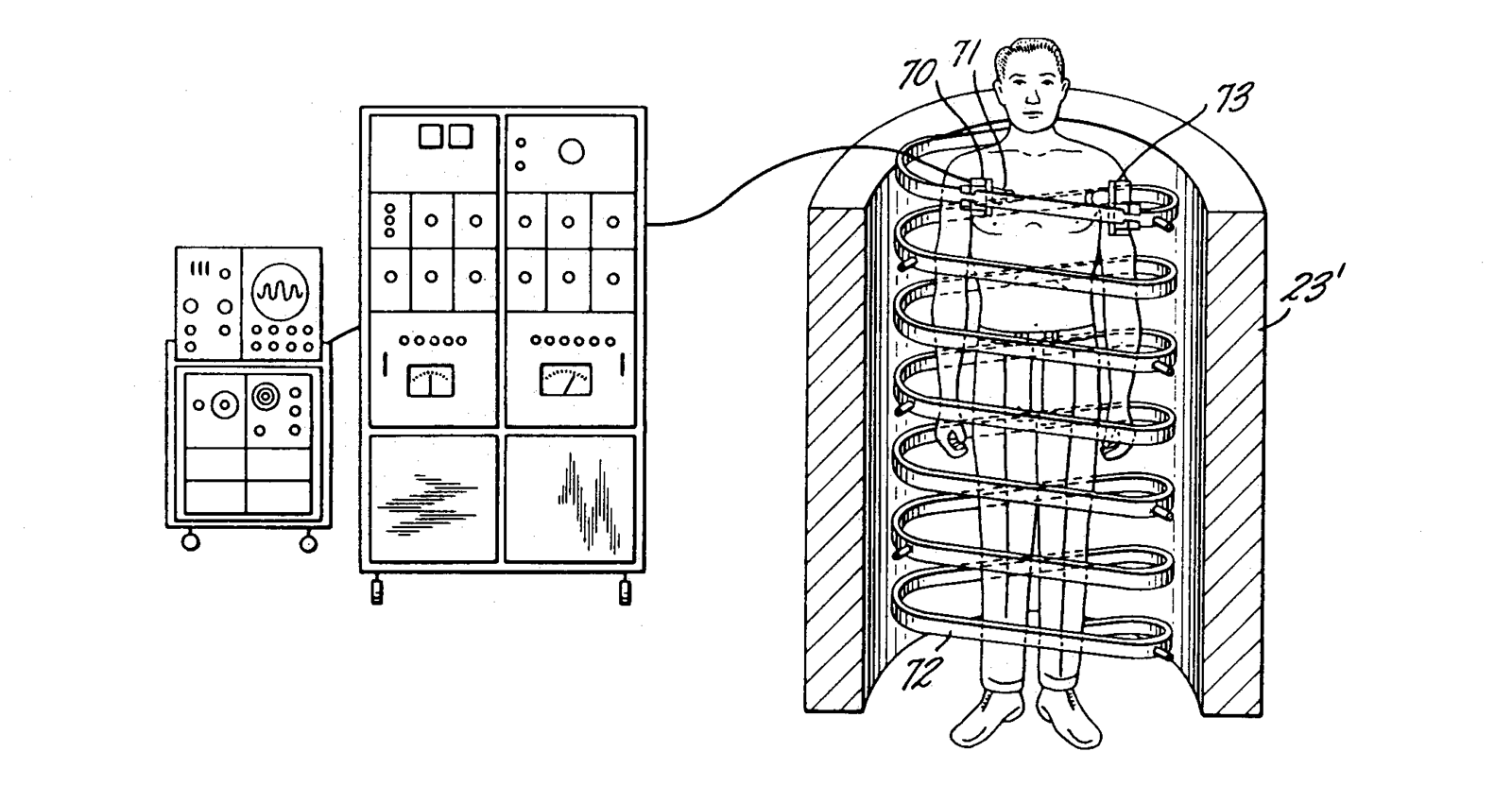

Cities of course need things like energy, sanitation, water, communication, and food. But does that mean they need the grids, sewers, pipes, carriers, and soil that currently provide them? Similarly, urban life cannot do without transportation, delivery, and emergency services, but what would it mean to provide these functions without cars, vans, or even roads? And more fundamentally, order is necessary, but perhaps planning isn’t. Economy is also necessary, but is currency? Cities need governance, but do they need governments? Such conjectures might appear hyperbolic, if not solipsistic, until we realize that it is only for a few, shrinking geographies that very existence of infrastructure—those hardened forms which functional demands led to in the past—can be presumed.

According to UN-Habitat, an additional 2.5 billion people will move to cities by 2050, 90% of which will be in Asia and Africa. In total, 3.5 billion people stand to live in communities without infrastructure. Providing conventional infrastructure to these places in the forms mentioned above would exceed the combined annual GDP of the USA, China, and Europe. Decentralization and autonomy can thus be understood not as a desire of the privileged, but rather a necessity of the poor. This necessity can be seen as a burden, there is also a particular opportunity that presents itself when spaces are not locked-in to antiquated forms of infrastructural providence. There is, in short, a “power of without.” What comes from without might not appear realistic today, but it very well might hold the keys for tomorrow.1 For as Buckminster Fuller once stated, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”2

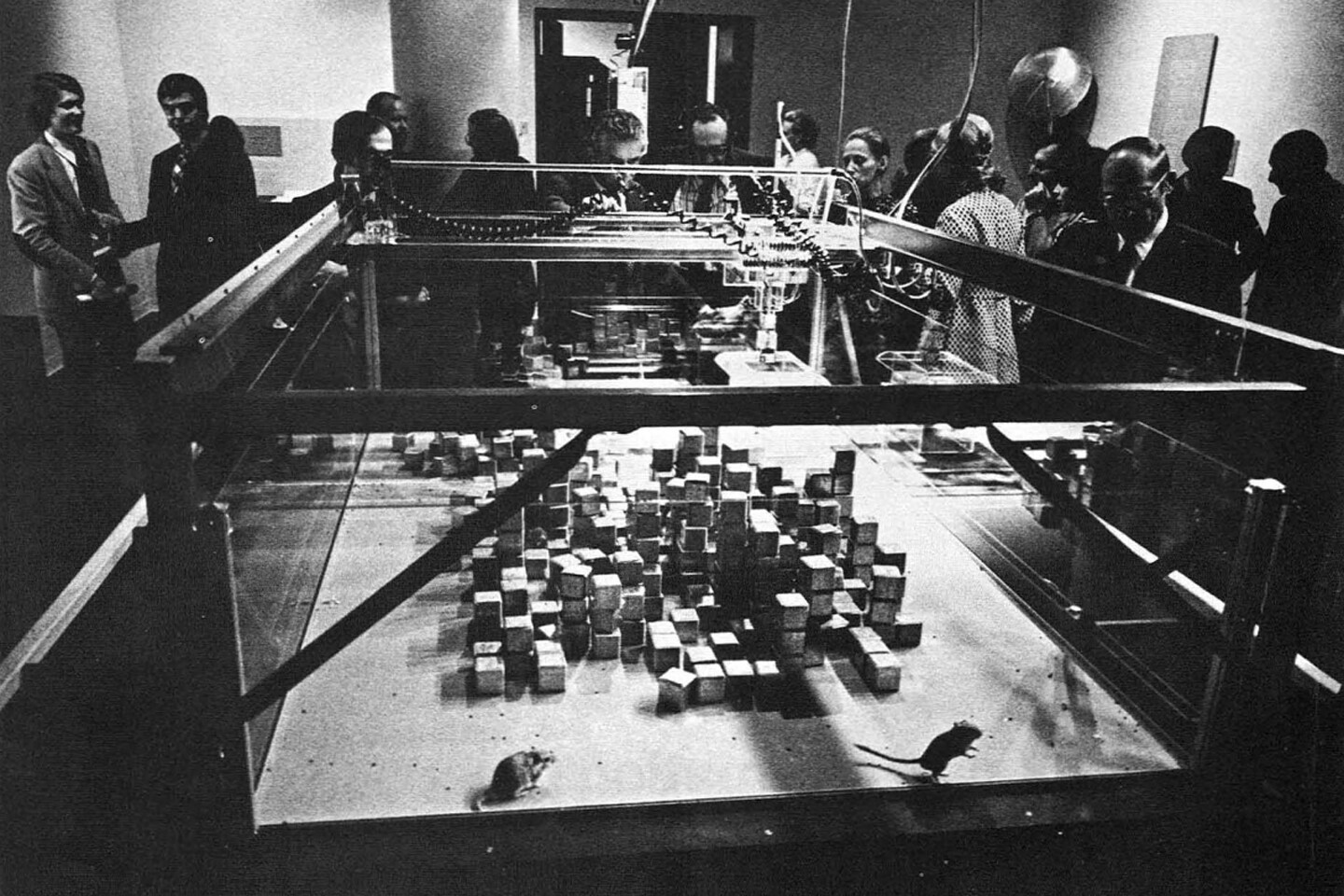

To return to Price, his declaration was made on the cusp of the digital revolution. Issues facing the future of urban settlement are vast, and the solutions that might be provided today are of a definitively different nature and performance than those that were possible during Price’s time. According to Nicholas Negroponte, all things digital are simultaneously local and global, large and small, inside and outside of any given boundary. The digital world is not crisp, but rather porous and diffuse. It brings together previously separate worlds, like those of discovery, invention, and expression. It has even become the DNA of each. The natural world and the artificial world are becoming the same. Change will happen very rapidly.

These questions and positions draw from the Foster Initiative for Autonomous Communities, a collaboration between the Norman Foster Foundation and the MIT Media Lab.

Quoted in L. Steven Sieden, A Fuller View: Buckminster Fuller’s Vision of Hope and Abundance for All (Studio City: Divine Arts Media, 2011), 358.

Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program.