How is it that books can so easily become friends?

Running her hand along the uneven and textured facade of her bookshelf, the spines shift ever so slightly beneath her fingertips. This ritual has become a type of nervous response to anxiety. The bookshelf sags with the weight of stories. It’s an old shelf that will fall apart soon, but for now it holds endless depictions of loss. Of all the things she has read here, all the friends she has made within these pages, she still feels so confused—lost. Rym lives in Toronto, far from where she was born, on the West Coast of the country; a landscape of ocean, mountain, dense forest, and moss.1 But now Rym is surrounded by buildings, highways, and swarms of people, where she proliferates. Through her life, Rym has always understood one thing: she isn’t white, and she isn’t obviously brown or obviously Native in the way that is expected. When confronted with ambiguity, it is often hard to allow a specific identifier to take hold, as it can be difficult to find out what that is. The perception that many have of something they don’t know—like Rym’s identity and origins—has so often in her travels lifted to the surface as confusion, the need to name her, and then an odd type of fear in their unknowing. She feels this fear too, because, in this country, she’s not safe. Few Indigenous women are.

Cities have this way of enveloping you: allowing you to become insignificant should you so choose, or, in contrast, to grow immense possibilities of visibility. Rym fled the West Coast over a decade ago. She wasn’t fleeing anything in particular, but rather a sense of dread, as though she couldn’t be who she needed to be there. It was too close. Too many people expected so much of her, and she wasn’t ready.

Since she left, Rym has allowed herself to move into anonymity. But there was always something about her; people would focus on her. The more she hid in reading, the more visible she became. It is quite ironic: the people who most do not want to be seen are almost sure to be found. Recently, Rym noticed a hardening in herself. This emotional hardening had become impossible to ignore, with anxiety and frustration coming more quickly, tiredness gaining momentum, a general irritation, and a loss of control. It is hard to tell how much of this hardening had come due to ageing or to the ongoing perseverance of racism and sexism she faces in her day-to-day life, but regardless, it had become a notable presence in her waking life.

As Rym began this ritual of focusing on her books, she wrote down the dream she had a few hours ago. It was vivid—tirelessly vivid. There was a moment when she felt as though it was actually happening, but her logic convinced her otherwise.

I found myself at the edge of a substantial hole. It was a human-made hole, that was for certain, perhaps a mine or a quarry, but why was I here? I couldn’t understand where this landscape came from. I had never actually seen a mine other than in photos, yet there was an overwhelming sense of fear as I stood at the edge. It was steep and was perhaps miles deep. I worried that I was standing too close to the edge and that I might fall to what would surely be my death. I looked to the edges of the mine. Everything was grey. Even the woods that surrounded the mine were grey, which I only now understand was because they all were dead.

I tried to move my feet backwards, away from the edge, but suddenly my body began to run along the edge, as if tracing it. It ran faster and faster right along the jagged edge of the steep decline into the hole while my mind fought logic and fear.

Then, my body jumped in.

Rym stood in front of her bookshelf and thought back to about ten years ago, when she was sitting in the back of a car with an old friend—someone who is no longer really a friend; they grew apart as they grew older, as so often happens. Her friend was smart and knew a lot about everything, but Rym always wondered if her friend truly knew a lot, or if she was just better at sounding certain, like so many white women are. “That’s a thought for a future essay …,” Rym thought to herself. Perhaps there was a book in this shelf that could offer perspective on the certainty that so many white women carry themselves with. “Aha,” she said aloud, “there’s one.” Already mapping the citation in her essay, she pulled down Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies (2020) by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.

“Perfect.”

In the back of that car so long ago, Rym had been listening to this friend tell her about an essay that she had written as an undergrad that she had received an A+ on. The essay was about the involvement of Dene people in uranium mining in Canada. Apparently, according to her friend, Dene were recruited/forced to mine uranium in the Northwest Territories, for the uranium that would later be used in some of the first atomic bombs, including the ones used in Hiroshima. Her friend was more curious, however, on the lasting impacts of that mining effort on Dene communities today. Even though uranium mining ceased operations long ago, miners had been carrying uranium out from the site in cloth sacs on their backs, and waterways were polluted by the mining efforts. So Dene communities in the area now suffer greatly from cancer. There is also a film made about this from 1999, called The Village of Widows. The majority of the men involved in the mining died, as well as many, many offspring.

As she listened, Rym’s spine began to tense and her neck started to feel a shivering or tingling sensation that made her feel uneasy. Or maybe, she considered, she was actually just getting carsick. Oh yes, she was carsick.

“Can you please pull over? I think I’m going to be sick,” Rym asked the cab driver.

The sad part about that car ride—well, there are too many sad parts to count—but a sad moment for Rym, one that she only later realized, was that she was learning about a history of her own people from someone else, someone who had no connection to it other than academic interest. Rym’s ancestors were forced to leave the Sahtu region of the Northwest Territories because of residential schooling. She didn’t, and still doesn’t, have any connection to the area or family that still lives there, but her friend’s story spoke to something deep within her.

It wasn’t so much a jump, but a dive, which felt odd. The mine—it was definitely a mine— sloped inwards towards the bottom. The dirt looked dead, as though it had been sucked of all nutrients and microorganisms. It was a seemingly unending moment of fear, but my conscious mind told me that I would wake up soon. These falling dreams almost always end before you hit the ground, they say. But I had never had a dream like this one before. Would I wake up soon? With the thought of possibly not waking up before hitting the ground, I started to panic again. In my panic, my stomach turned. As the ground came closer and closer, I thought about how nice it would be to have my morning coffee soon. I really love opening my curtains in the morning with my cup of coffee, letting the first glimpsed of light seep through the window. With that thought, my hands turned cold, then my spine tingled from the base to my neck. I couldn’t tell if this was happening in my dream, or whether my body was no longer under the covers. Then suddenly, I landed on the ground. It wasn’t elegant, but I also didn’t die, which was unexpected—even though they say you can’t die in your dreams.

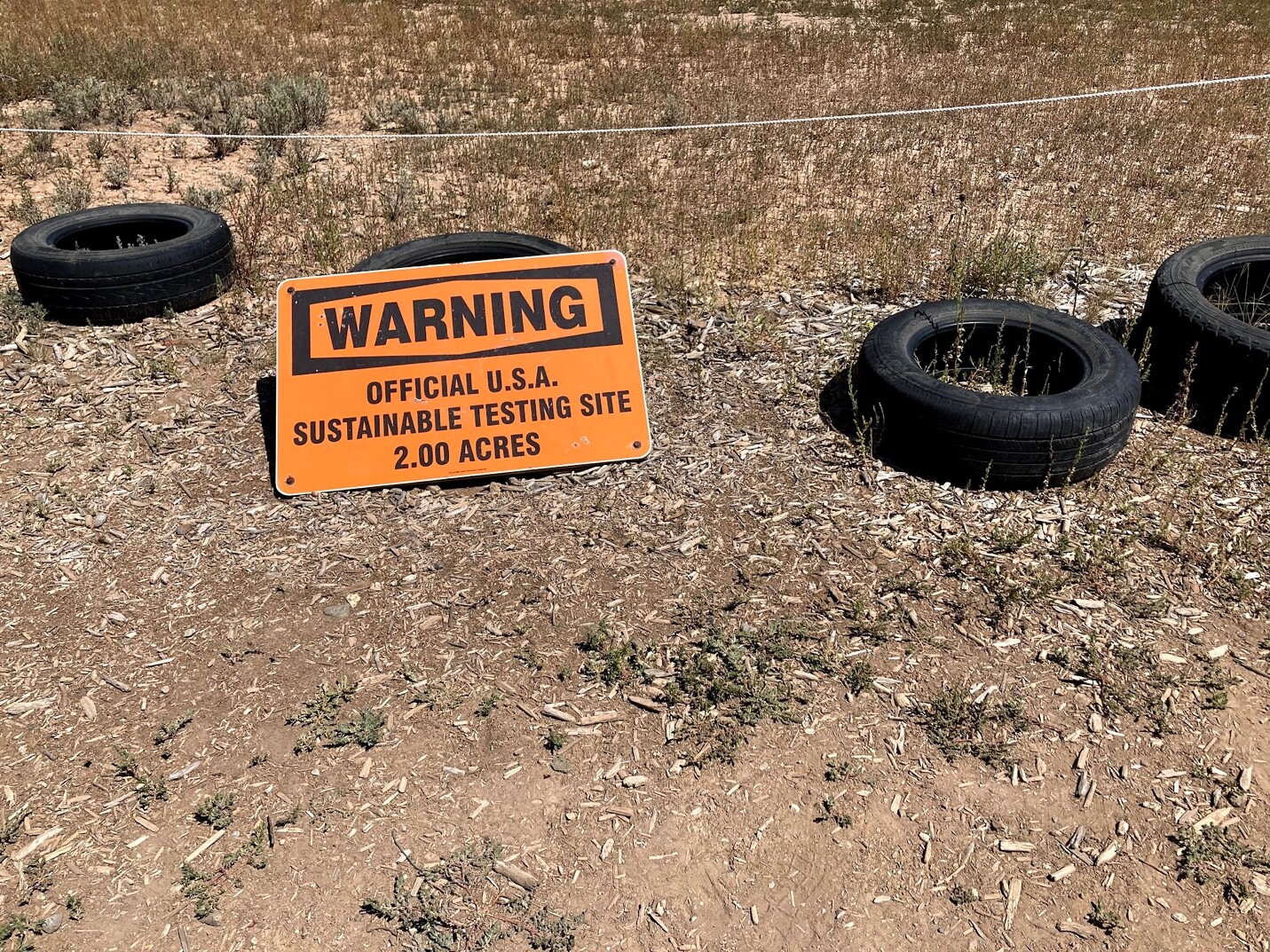

Ts̱ēmā Igharas & Erin Siddall, Great Bear Money Rock, 2021–2022. Co-commissioned by Toronto Biennial of Art and Momenta Biennale de l’image. Photo: Rebecca Tisdelle-Macias.

According to the World Nuclear Association’s website, Canada had been the largest producer of uranium (approximately 22% of world production) until 2009. Rym started casually researching the history of Dene uranium mining since her friend first told her about it. A few years ago, Rym attended an exhibition opening where Tahltan artist Ts̱ēmā Igharas installed an artwork and was performing. It was there that Rym learned how Ts̱ēmā spoke about the damage of uranium mining in the Northwest Territories through her artistic works. In another of Ts̱ēmā’s installations, created in collaboration with Erin Siddall, radioactive stones were gathered from Great Bear Lake, the lake that was the site for the first uranium mine in Canada, Port Radium. Ts̱ēmā and Erin created delicate glass forms to encompass the radioactive stones and placed them across the floor, where they reflected light from a 16mm glass prism projection.

The mine, as it turns out, was abandoned. I sensed that some of the leftover, broken parts of machinery had seen many winters. There was something there, however, something vibrating in the ground under and around me.

Cities have so often been seen as a meeting place of many peoples, histories, ecologies, and perspectives. Knowing this gives Rym comfort in having lived away from home for as long as she has, for cities have such a unique ability to become an assembly of generations that have passed through across time. Rym read The City We Became by N. K. Jemisin at a time when she was questioning what it means to belong with her own sense of belonging. In the story, each of the five boroughs of New York City are embodied by five individuals who become the physical representations and protectors of their boroughs, and collectively of New York City itself. The characters portrayed such complex relationships to belonging that Rym carried their energy from the pages with her. There is one moment in the book the stood out in particular, when the Bronx (Bronca) danced on ancestor stones in a park at the edge of the borough, looking over the Harlem River. She then raised her arms, and with her movement, the river rose towards the sky, as if becoming extensions of her arms. More than simple science fiction, this depiction portrays a Lenape woman that has a deep relation with her lands; a reminder for many Indigenous peoples of these connections we have, of the fact that our bodies are uniquely tied to the land whether we want it to be or not. Manhattan (Manny) is also a unique character that Rym finds connection to. Manhattan, conversely, is not from New York. In fact, he had just arrived in the city when strange occurrences began, but he quickly became one of its protectors. In The City We Became, the personifications of the five boroughs show not just how people find relationships with where they live based on their unique positionalities, but also how they become the land and the city itself, with both the ability to protect it as well as to destroy it.

Quickly, almost imperceptibly at first, the seemingly dead or contaminated dirt began to vibrate and slowly fall downward, towards me. As I looked up and saw the appearance of the mine blur with the subtle motion, it all stopped. Confused, I began looking around. I clearly needed to get out of there. Sensing that I had to do something to get myself out of there, I glanced back down at the ground, trying to analyze the dirt, unsure of what I would find. The vibrations then began again, only this time more forcefully. My body tensed to brace against the shaking, but the more I tensed the more the earth shook. I pictured the walls of the mine collapsing in on itself, on me. Then I began to run, upwards this time. The harder I ran, the more the mine caved in on itself.

Somehow, I got out of the mine and was again standing along its edge, looking back at what was now a sunken space of contaminated dirt. Even though it was a dream, it was hard to imagine that my body was the starting point of what collapsed the mine. I quickly started to sense that I was no longer alone, and felt the urgent need to get out of there, fast. So I ran, and that same vibration of energy followed me, pushing me up and faster along the ground.

When I felt I had run far enough, I stopped, staying still for a moment. I still felt the vibration, but this time it wasn’t coming from the dirt; it was coming from within me. It was then that I realized it was me who was moving the ground—it was me who had demolished that old uranium mine next to the lake.

When Rym had woken up from the dream earlier this morning, her body had been covered in sweat. She felt ill, similar to that feeling of carsickness from so many years ago. In an attempt to get herself out of it, Rym made her coffee, opened her blinds, let the sun bathe across her recently woken body, and turned to her bookshelf. Standing there, now in a trance, still feeling ill, Rym tries to settle a feeling awakened from somewhere deep within that she isn’t able to fully describe yet. She sensed the mine; she had become the energy pulled up through and with the dirt. She still felt that she was the vibration of the earth. Continuing to stand there, the illness eventually subsided. But a new feeling started to emerge. Rym’s hands became cold, and the books that lined her sagging bookshelves slowly started to vibrate.

Bookshelf

“How do you mourn something you can still see in the mirror?”2

Billy-Ray Belcourt, This Wound Is a World, ed. Micheline Maylor (Calgary, AB: Frontenac House Ltd., 2017).

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin Books, 2021).

Sue Goyette, Ocean (Kentville, NS: Gaspereau Press, 2013).

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008).

Peter Blow, Gil Gauvreau, Rick Bremness, Tanmayo Krupansky, Celestine Natale, Loretto Reid, George Vacval, and Gary Farmer, Village of Widows: The Story of the Sahtu Dene and the Atomic Bomb (Toronto, ON: Kinetic Video, 1999).

“Before I am honest / I want to witness / the beauty of a lie”3

Lee Maracle, Talking to the Diaspora (Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2015).

Caleb Azumah Nelson, Open Water (New York: Black Cat, 2021).

Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010).

Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies (Toronto, ON: House of Anansi Press Inc, 2020).

Rinaldo Walcott, On Property (Windsor, ON: Biblioasis, 2021).

“We all smile with the magic of this truth.”4

N. K. Jemisin, The City We Became, The Great Cities Trilogy (New York: Orbit, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, 2020).

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993).

Candice Hopkins, Katie Lawson, and Tairone Bastien, Water, Kinship, Belief (Toronto, ON: Toronto Biennial of Art and Art Metropole, 2022).

Kyla LeSage, Thumlee Drybones-Foliot, and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson eds., Ndè Sı̀ı̀ Wet’aɂà: Northern Indigenous Voices on Land, Life, & Art (Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2021).

“Matter causes spacetime to bend around it.”5

“Light has to obey the contours of spacetime.”6

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred, (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021).

Virginia Woolf, Moments of Being (London: Hogarth Press, 1985).

Eve L. Ewing, Electric Arches (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017).

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: The Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2003).

Amanda Gorman, Call Us What We Carry: Poems (New York: Viking, 2021).

Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

Bryum argenteum is an often unnoticed but omnipresent type of moss that is capable of existing in the most unlivable places, like under the trampling feet of city dwellers in the cracks of pavement. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: The Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2003). Kimmerer describes Byrum argenteum as a common type of urban moss, able to move freely through the air as its life forms take many shapes. As it is dispersed through air, it travels across the world and is found in cities globally, but, as Kimmerer states, “the much more common route for dispersal is by footsteps … the broken tips, scuffed along by a pedestrian, will take hold in another sidewalk spreading Silvery Byrum all over the city” (Kimmerer, Gathering Moss, 93)

Billy-Ray Belcourt, This Wound Is a World, ed. Micheline Maylor (Calgary, AB: Frontenac House Ltd., 2017).

Lee Maracle, “On Honesty,” in Talking to the Diaspora (Winnipeg, MB: ARP Books, 2015).

N. K. Jemisin, The City We Became, The Great Cities Trilogy (New York: Orbit, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, 2020).

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021), 57.

Prescod-Weinstein, The Disordered Cosmos, 117.

Half-Life is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Art Institute of Chicago within the context of its exhibition “Static Range” by Himali Singh Soin.