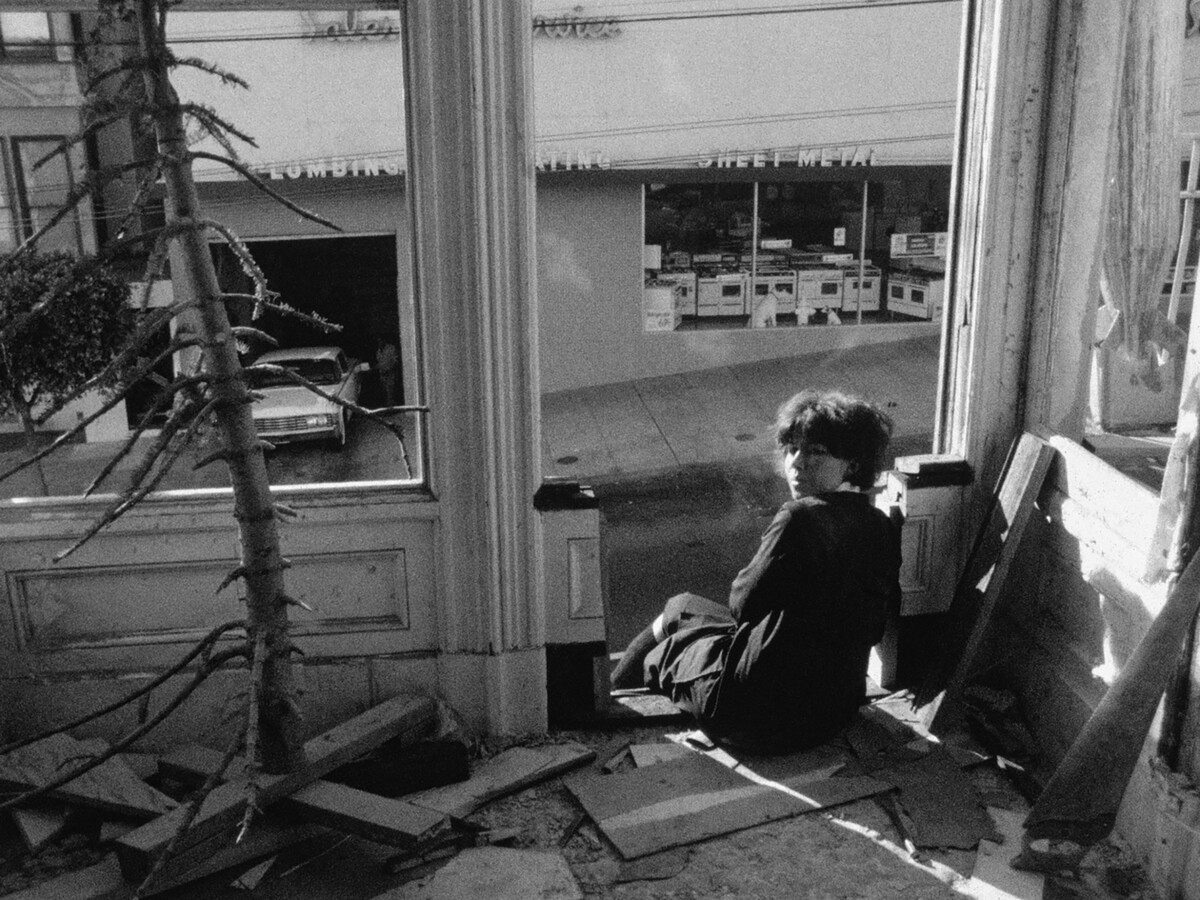

In November 1965 Jay DeFeo was evicted from her home and studio at 2322 Fillmore Street in San Francisco, the epicenter of a vibrant community of Beat-adjacent artists, writers, and musicians. In a now-famous story, the artist hired a moving company to box up and haul off her massive painting, The Rose, which she had labored over since 1958. Eleven feet tall, nearly a foot thick with sculpted oil paint, wooden armatures, and earlier drafts, and weighing 1,800 pounds, The Rose had to be hoisted out of her second-floor window.

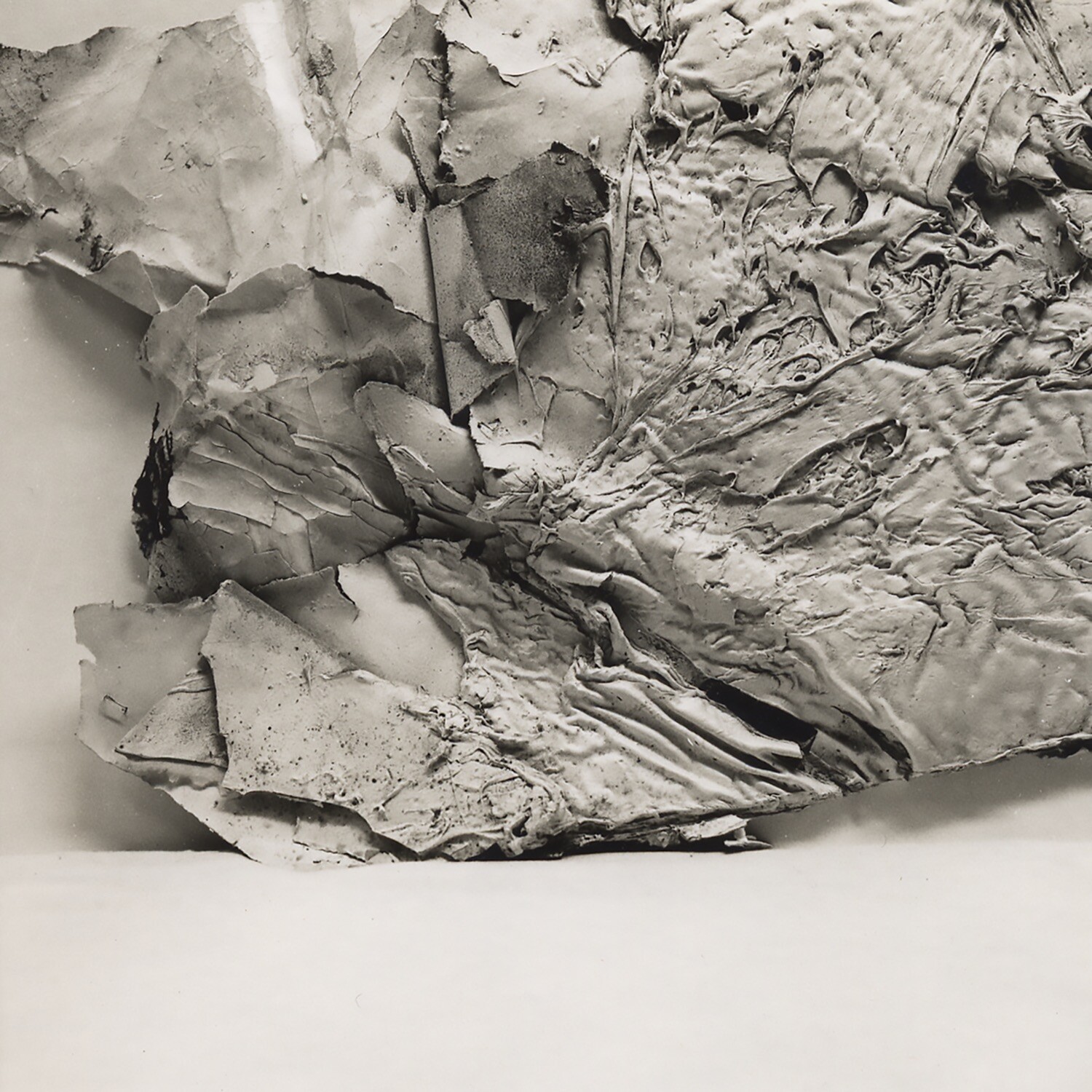

When DeFeo vacated the apartment the following day, she left behind another work in progress—a comparatively slight painting, in oil on paper, stapled directly to the wall. The artist was only able to salvage a few roughly torn fragments from the scarred and stuccoed surface of Estocada, as the piece was titled (after a matador’s final murderous blow). Though The Rose spent decades languishing in storage and was only exhibited twice during the artist’s lifetime, the painting and its legend have come to define DeFeo’s career. Estocada’s story, on the other hand, has remained untold. But how does one write the story of an artwork that never really existed, unfinished and undocumented in its time?

Jordan Stein, founder and curator of Cushion Works in San Francisco, grapples with this challenge at the outset of his new book: “How do we account for ghosts? We circle an absence. We listen for the artist’s voice, an echo. We go looking.” Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo’s Estocada & Other Pieces, both Stein’s first book and the first comprehensive study of Estocada, is a confident, probing, and pleasantly meandering account of his quest for the lost painting and its various remains. The author employs—perhaps by necessity, given the elusiveness of his subject—an atypical approach to art history, interjecting his main narrative with anecdotal vignettes on eight mercurial and generation-spanning Bay Area artists. Primarily constructed from Stein’s interviews and recollections, these stories echo and buttress the book’s themes: presence and absence, centers and edges, success and failure, loss and discovery.

DeFeo’s story usually begins and ends with The Rose, indulging what Stein calls “history’s hunger for the monolithic and mythological.” His challenge was to recover and transmit the undocumented history of Estocada, embracing both what is there and what is not without making too much of nothing. Rip Tales is well-researched and grounded in evidence, despite its unconventional structure. Stein, more artist-cum-curator than art historian, even waxes poetic about the material and metaphorical value of archives: “They are orderly places, quite unlike a life.” Given the relative dearth of literature on Estocada, the author relies largely on primary sources, including DeFeo’s own recollections, culled from oral histories, a slide lecture, and her private journals; the estate’s holdings; and his own interviews. Stein’s achievement lies less in having discovered or reconstructed an unknown artwork, but rather in so successfully piecing together its scattered representations, found among and within obscure artworks and DeFeo’s countless photographs of her studio.

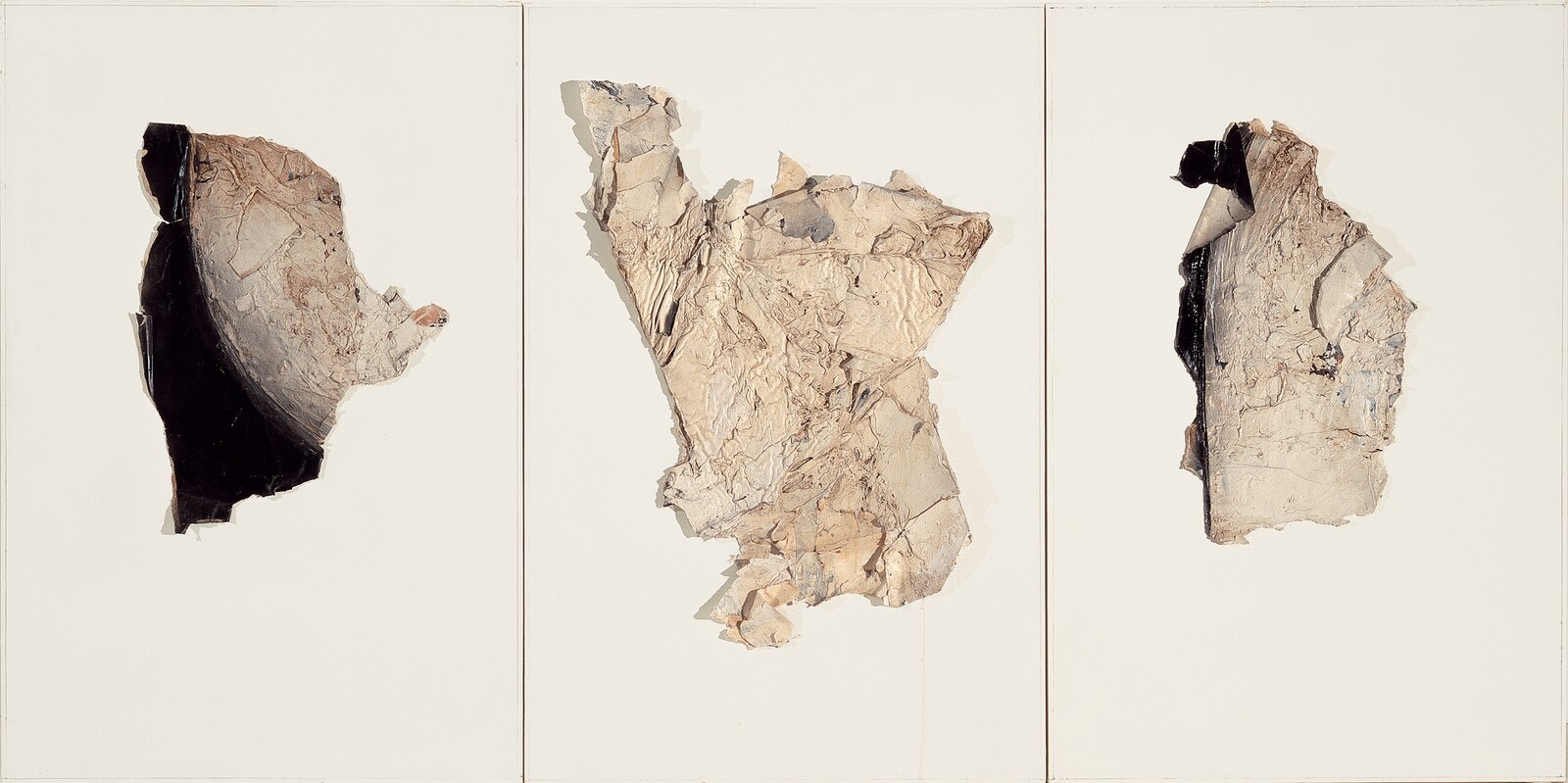

As Stein documents, Estocada’s remnants spent years under DeFeo’s bed, accumulating dust and grime during a period of inactivity for the artist. She very nearly disposed of them all; instead, she sprayed three of the four bark-like fragments with fixative, permanently sealing in their “underbed residue,” in Stein’s evocative phrase. The artist then mounted these to white boards to form Tuxedo Junction (1965/1974)—the triptych’s vast negative spaces evoke Estocada’s irretrievable gaps.

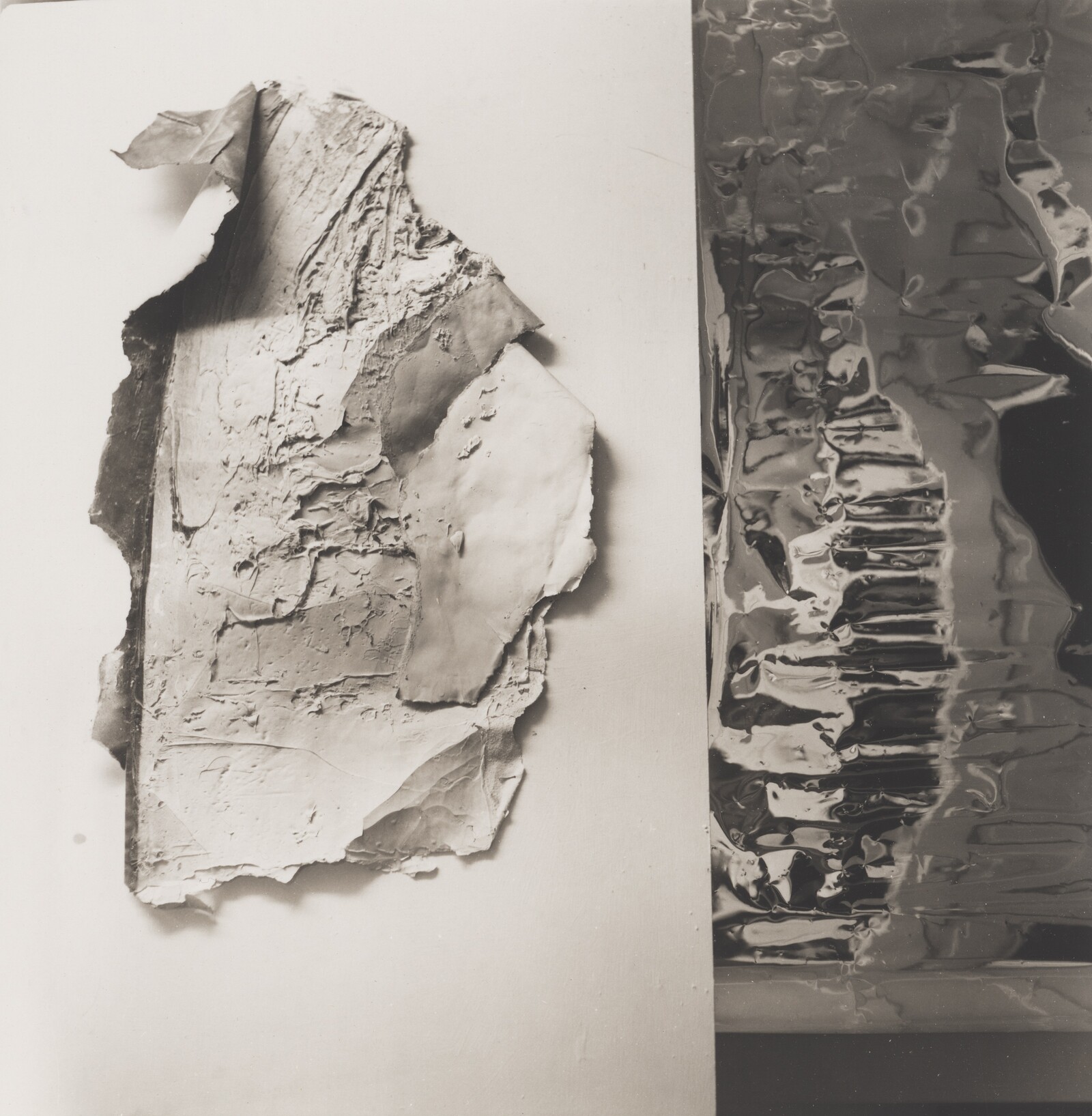

DeFeo never photographed Estocada before its demise, yet the work—or some version of it—survives in large part due to the photographic details she took of the fragments in 1973. Later, she reimagined Estocada once again, slicing up and deconstructing her own images to create a series of collages and photocopies. Stein relates this recursive imagery to DeFeo’s broader effort to transform her studio and its contents into an ever-evolving work of art by photographing it: “She turned process on itself, made a meal of it.” Stein’s study justifiably positions the Estocada and its various by-products at the center of the artist’s more experimental practice in the 1970s.

Just when the reader may want Stein to dig deeper and explore the implications of DeFeo’s photographic self-reflection or her propensity to salvage and repurpose pieces of aborted paintings (Estocada was not the only one), he pivots. The author takes many digressions along the way, regularly interrupting the slow-developing story of Estocada to tell brief anecdotes related to eight other Bay Area artists, including Lutz Bacher, Vincent Fecteau, Dewey Crumpler, and Ruth Asawa. These interludes can disrupt the narrative flow, yet they reveal subtle connections and affinities with Stein’s main subject. One chapter explores a previously unknown cache of around 9,000 Polaroid self-portraits of April Dawn Alison (the suppressed alter ego of the commercial photographer Alan D. Schaefer), who appears in a variety of stock pin-up poses: donning elegant cocktail dresses and tight mini-skirts; bound by handcuffs; and frequently posing for the camera while clutching another camera, confusing our sense of photographer, viewer, and subject. Alison’s story, as told to Stein by Andrew Masullo, who came into possession of Schaefer’s photographs, reminds readers that art is often secreted away, for varying reasons, in closets, storage facilities, and even under beds.

Stein’s interludes form a community of like-minded individuals around DeFeo—the curator’s book is a group show of sorts. Its fragmentary structure successfully mirrors DeFeo’s nonlinear process, Estocada’s numerous iterations, and the fits and starts of any artistic endeavor. Throughout the book, Stein reminds us of art’s fragile and stubborn materiality, but also the ways in which art can transcend its objectness: “[Art] is always on its way, too complicated to be a noun and ineffectively contained in form.” By exploring the many afterlives of Estocada, Stein embraces the multiplicity and mutability of any artwork. What, after all, constitutes the work? Is it the unfinished painting; the surviving fragments or their photographic variations; Tuxedo Junction; or something larger? Stein implicitly proposes that Estocada is a constellation of objects, images, and stories. This living art history reframes the loss and failure of DeFeo’s abandoned painting as boundless potential.

Jordan Stein’s Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo’s Estocada & Other Pieces was published by Soberscove Press in December 2021.