Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

April 9, 2021 – Review

Joachim Bandau’s “Die Nichtschönen. Werke 1967–1974”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

At the entrance to Joachim Bandau’s Basel exhibition stands Großes weißes Tor [Large White Gate] (1969/1970), a trio of tall, shiny white columns, each sprouting buffed shoulders and arms that conjoin with its neighbors. Born in Cologne in 1936, Bandau’s childhood was marked by World War Two. He determined to be an artist at 13, after a visit to a Paul Klee exhibition, and went on to study at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, just ahead of Gerhard Richter and Imi Knoebel. Nonetheless, he grew up in the shadow of the figurative sculpture with which the National Socialists underpinned their credo of racial superiority—like Karl Albiker’s strapping athletes that still welcome visitors to Berlin’s Olympic Park—and began to counter this mechanical perfection in his own work. The anthropomorphic columns of Großes weißes Tor make unconvincing titans: the arms might just be thighs; the bulges don’t swell where they ought to. And the structure is modular, easily assembled and just as easily tidied away. It’s a collaged acropolis for a time of jerky social reconfiguration.

The initial mood of this selective retrospective, a survey of Bandau’s Nichtschönen [Non-beauties] from 1967 to 1974, is black humor. The Nichtschönen are generously proportioned, fiberglass-reinforced polyester forms, sometimes with …

February 24, 2020 – Review

Camille Blatrix’s “Standby Mice Station”

Aoife Rosenmeyer

As is often the case in public institutions, the provision for small children at this show is minimal. An activity table in the middle of the spartan gallery draws attention to the bare floor surrounding it. In Camille Blatrix’s latest test of how spare an exhibition can be, the large, sky-lit space at the Kunsthalle Basel houses four small wooden marquetry pictures and a number of low (and low-key) sculptures. And in the same main gallery there’s a poster—like the activity table, it’s not listed as an artwork—that signposts the nearest Starbucks. Might we find more comfort there? Presenting quasi-artworks that don’t quite fulfil their purposes and signs that direct us back out again, Blatrix interrogates our reasons for coming to the kunsthalle. Are we here for entertainment or aesthetic stimulation, to find something familiar or novel, personal or institutional?

In two small, dimly lit galleries beyond the main space, Hugo Benayoun Bost’s remix of the eight-bar intro to Stand by Me, the 1961 Ben E. King song behind the title of Rob Reiner’s 1986 film, loops, continually heightening and—almost—releasing tension. The artist’s alter ego, another non-artwork, sits crumpled in one corner: a crying face drawn on an old …

February 21, 2019 – Review

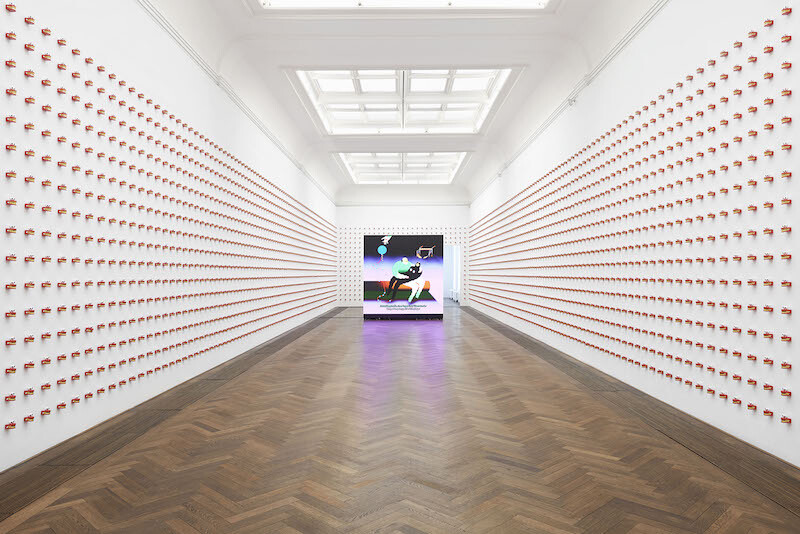

Wong Ping’s “Golden Shower”

Chloe Stead

Without wanting to yuck someone else’s yum (as the saying goes), the breathless list of perversities on view in “Golden Shower”—Wong Ping’s first solo exhibition at a major institution—is enough to make an adult film star blush. There’s the elderly man who gets off on the smell of his pregnant daughter-in-law’s soiled underwear; the husband who darkly fantasizes about turning invisible and sodomizing a police officer; and the teenager who’s obsessed with the, shall we say, unusual placement of his classmate’s breasts on her back. All of this in sharp contrast to the relentlessly cheerful aesthetic of the films themselves, which bring to mind the color-saturated, blocky simplicity of 1980s computer games. It’s this world that the cross-generational protagonists of Ping’s animations must navigate; and they are not handling it well.

Misogynist, violent, and jealousy-fuelled thoughts consume the minds of Ping’s characters, which we hear mostly in first-person accounts, read by the artist himself in deadpan Cantonese. But the activities in each of the seven films featured in the exhibition are communicated free of judgment and—excluding part one and two of “Wong’s Fables” (2018 and 2019 respectively), which are moralistic by design—any discernible lesson. If anything, there is an element of …

June 17, 2012 – Feature

Art Basel roundup

Laura McLean-Ferris

Jeff Koons’s giant blue egg sculpture—that outlandishly chatoyant and seductive object—looks as though it could have landed from another planet or another time. Its cracked top serves as a reminder of the way that Koons created a fundamental fracture within art history with his compelling work, and I was reminded of the artist’s monumental impact as I visited his exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler coinciding with the Art Basel fair, partly because it informed nearly everything I saw subsequently. The very first work in the show is the utterly eerie The New Jeff Koons (1980), a lightbox displaying an image of the artist as a young boy posing with crayons and a coloring book like the perfect child, his expression every bit the airy adult Jeff we have come to know: clear-eyed, polite and unnervingly serene, with his “how may I help you” smile. This image serves as an introduction to the artist’s brilliant Hoover sculptures and shampoo polishers in Plexiglas cubes, which revel in the purity of their box-fresh newness and aspirational product names—Celebrity and so forth, and assisted by Koons’s presentation and uncanny doublings. These, now more than thirty years old, are nothing short of visionary. They seem …

June 19, 2011 – Feature

Art Basel roundup

Vivian Sky Rehberg

One hears a lot of grumbling about Art Basel. Or maybe it’s just the leftist company I keep. Still, I was surprised to meet more than a few people who had travelled all the way to Basel for reasons peripherally related to the fair but who had refused to step foot in it, according to the misguided “principle” that blinding oneself to the commerce of art is proof of genuine anti-capitalist credentials. Whatever happened to “know thine enemy”? And is the fair really the enemy? Well, historical materialists like me don’t believe in fairy tales and—guess what?—ignoring the art market does not make it go away. My choreographed wander through the behemoth Hall 2 was exhausting, terribly instructive and, in some cases, more aesthetically gratifying than many of the exhibitions I’ve recently seen in non-profit institutions.

Worth the trip alone: Isabella Bortolozzi’s stand, especially Carol Rama’s Movimento e Immobilita’ di Birnam (1977) with its limp bouquet of flaccid black rubber bicycle tire tubes, visually spare yet enticing. In an entirely different register, at Air de Paris, I didn’t know how to quit Dorothy Iannone’s Brokeback Mountain (2010), a brightly painted freestanding object, like a miniature altar, featuring portraits of the characters …