Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

February 9, 2024 – Review

Astrid Klein

Xenia Benivolski

Astrid Klein’s photowork Untitled (Je ne parle pas,…) (1979) presents two cut-out images of Brigitte Bardot—posing in a baby doll dress and, again, coquettishly looking back over her shoulder. In broken, typewritten French and English are the words “je ne parle pas, je ne pense rien” (“I don’t speak, I don’t think”) and “to paint my life, to paint my life, so many ways.” It’s a fitting prelude to this exhibition, which is something of a house of mirrors. Trapped behind the museum glass, like sexy cats in apartment windows, large photographic works fill the walls, each featuring a beautiful woman while slyly reflecting the viewer. In Untitled (la sans couleur…) (1979), a reclining woman awkwardly turns her head to look at me with an enigmatic smile. Loosely draped in a sheet on an unmade bed in the dark, she is a body in waiting. These gazes are not exactly inviting; if anything, they somehow lack emotion, as the title reflects: “masks without color.” But there is something cool, even powerful, about their magnetic resignation. Like several in the show, the image is arranged with visible marker framing and taped sections, giving the impression that this composition sets the stage …

July 21, 2023 – Review

Martine Syms’s “Loser Back Home”

Juliana Halpert

In an early scene of The African Desperate (2022), Martine Syms’s first feature film, her protagonist, a Master of Fine Arts candidate named Palace, hosts four professors in her studio for a final review. In turn, each teacher performs their own version of art pedagogy in Palace’s general direction, lobbing vague questions and cloudy critiques her way. “It’s all just so figurative,” comments Rose, the snidest, and most overtly racist, of the bunch (played perfectly by Syms’s longtime gallerist, Bridget Donahue). She gestures at the work: “It’s just a family, right?” Palace, skeptical and evasive up until this point, finally shoots back: “Haven’t you read Saidiya Hartman? Of course I’m responding to the African desperate. Staking my claim to opacity.”

Opacity is the name of Syms’s game in “Loser Back Home,” the artist’s first exhibition with Sprüth Magers, in her native Los Angeles. That scene was at the front of my mind as I toured the two floors, attempting to parse the show’s manifold logics, feeling a bit rebuffed at every turn. Opacity—and the right to stake one’s claim to it—was a concept crafted by Édouard Glissant in his Poetics of Relation (1990) as a means of protecting and preserving …

May 20, 2022 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

In the local elections held the week before London Gallery Weekend, the residents of Westminster City Council, which covers much of central London, voted Labour into a majority for the first time since the council’s creation in 1964. The vote was partly informed by the Conservative council’s misguided decision, widely publicized in 2021, to spend six million pounds on the “Marble Arch Mound,” a twenty-five-meter-tall astroturf hill and viewing point designed to lure viewers back to the city’s busiest shopping district. It failed: many stores are still covered with for-rent signs, one of which peddled a “blank canvas for new ideas.” These are the visual and linguistic relics of the before-time: they represent old ideas of urban environments and their inhabitants’ habits, and beg the question, “What if we don’t want to return to how things were?”

At Emalin, Augustas Serapinas is displaying eight large black reliefs made of roof shingles taken from a wooden house from his home country, Lithuania. Many of these traditional architectures are now abandoned or destroyed and used for firewood. Serapinas bought one, broke it apart, charred its roof shingles, and repurposed them into monochromes that are part-painting, part-sculpture. They are heavy, loaded with their …

October 7, 2019 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

%20provisioning_hr.jpg,1600)

The world is burning. This is not a metaphor. The sky is bleached a searing lime green, tinged with burned orange that reflects off relentless choppy waves. Suddenly, the sky goes blood red and the horizon blackens, the sun a dull hole punched in the sky. Our view shifts, panning quickly to the left, then back again, as if searching for something, anything. The sky then changes again to a blinding sherbet yellow. The screen depicting this scene, mounted on a metal rack above a whirring circuit board, gives us a certain vision of our current reality. The shifting colors are a translation of information from a small atmospheric monitor mounted on the back of the rack. It’s not clear what directly causes the hues to brighten or waves to get that bit higher or more intense in Yuri Pattison’s sun[set] provisioning (2019) at mother’s tankstation—whether the car exhaust from the street outside, or the hungover breath from bodies in the room might make the scene that bit more trippy. The contraption offers a heavily mediated fiction, but it also makes an actuality visible and present: a drowned world, made hallucinatory and beautiful by toxins that saturate the air and …

October 12, 2018 – Feature

London Roundup

Mariana Cánepa Luna

Just as Frieze Art Fair opened last Wednesday, Prime Minister Theresa May gave her keynote speech—and dared to dance again—at the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham. She announced that freedom of movement would be terminated “once and for all” by limiting access to “highly skilled workers” (in short, migrants earning over 30,000 British pounds per year). Countless art professionals earn much less (including entry-level curatorial staff at Tate, and yours truly), as well as doubtless many of the myriad gallery and museum folks involved in the city-wide jamboree of Frieze week. How do we imagine London’s contemporary art ecology post-Brexit, a scene that has grown exponentially since Tate Modern’s opening in 2000 and the first Frieze Art Fair in 2003? The question of how the 2019 edition of the fair is going to be affected was the elephant in the tent. Most people I asked shrugged: negotiations are still ongoing, consequences are yet to be seen. “It’ll be fiiiiine,” a London museum director told me. “Maybe we’ll visit a smaller fair, like the first editions—remember those days?” opined a British gallerist friend working in New York. Although one could put this upbeat denial down to the cliché of dark British …

October 21, 2016 – Review

Hanne Darboven

Jonathan Griffin

Rows of numbers instill in me a sickening panic. I got that feeling, familiar from childhood mathematics lessons and annual tax returns, in Hanne Darboven’s current exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles.

Perhaps there was no need for such histrionics. In 1973, the West German Darboven told the writer Lucy Lippard that her art has “nothing to do with mathematics. Nothing!” For Darboven, numbers were a means of marking out time and space, “writing without describing.” For the most part, her work is not as concerned with calculation as with counting. Numbers, written sequentially, are akin to seconds ticking on a clock, days counted on a calendar or beats in a piece of music. (Indeed, in 1979 Darboven developed a system of musical notation which she used until the end of her life, in 2009, to write compositions for chamber orchestras and string quartets.)

Darboven’s work generally consists of gridded pages of annotations and numerical inscriptions, sometimes handwritten, sometimes typed or printed; in 1978 she began including collaged elements such as her photographs and cuttings from books. In a single work, these pages can number in the hundreds or thousands. On the ground floor of the gallery, the staggering Erdkunde I, II, …

February 25, 2014 – Review

Alexandre Singh’s “The Humans”

JJ Charlesworth

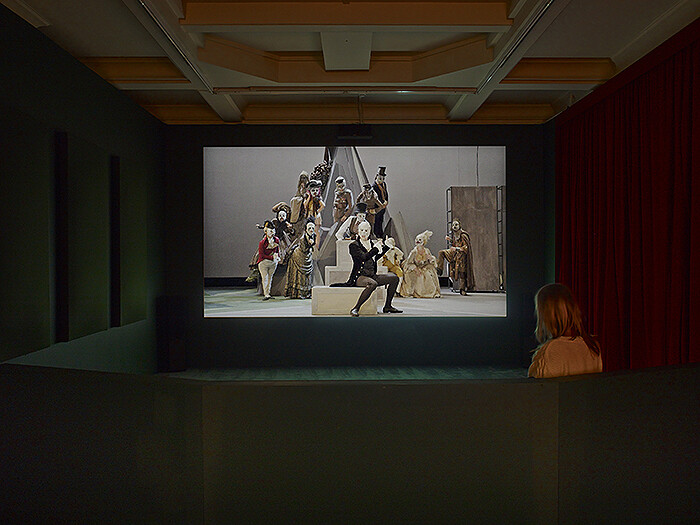

Alexandre Singh’s spectacular, ambitious project The Humans (2013) is not the easiest artwork to discuss. A three-hour, three-act play with music-and-dance numbers, The Humans presents the audience with a wildly absurd remix of an origins-of-man narrative, borrowing and stealing from the Bible, the classics, Shakespeare, and other references too numerous and intertwined to keep straight, all presented in a self-conscious fusion of styles—Greek comedy, Commedia dell’arte, and Broadway musical. It tells a tale of the Apollonian and Dionysian dualism at the heart of humanity, and is, to say the least, engagingly bonkers.

Rotterdam’s Witte de With, where The Humans premiered in September last year, and New York’s Performa biennial, where it ran again in October, both commissioned Singh’s work. Here, at commercial gallery Sprüth Magers, a full-length, for-camera performance is projected in high definition, while the rest of the show includes works on paper, sculptures, photographs, and props either preparatory to, or drawn from, the production itself.

The realities of commissioning and production captured in these objects are certainly not trivial. As much as one might enjoy, and perhaps wish to acquire, the static art objects on view, this exhibition hinges upon our understanding of the process behind the kind of artwork …

September 20, 2012 – Review

Thea Djordjadze’s “Spoons Are Different”

Laura McLean-Ferris

Come inside and I will draw the curtains—shut out the streets and the harsh brightness of day in favor of dim bluish light. And we will find ourselves in a small beautifully proportioned room. You will immediately understand that this is a private space—an environment meant for one person or two. And what will we do here? What has been done before, in this building, located on a gentile Mayfair corner?

In her treatment of Sprüth Magers’s small London space, the Georgian artist Thea Djordjadze has created a psychologically freighted interior. The title “Spoons Are Different” shares a sense of near-familiarity with her work: forms of smudged clarity that we can almost read and fully comprehend, but not quite. As well as installing sets of long, sheer royal blue curtains in front of the gallery’s large windows, the artist has laid sculptures around the interior as though they were items of furniture designed for contemplative purpose. A steel sculpture, Untitled, (all works 2012), has the spindly two-legged proportions of a small desk, a bureau or even a tiny piano, as rendered in outline or frame, yet it is fixed to the wall at a skewed angle, one foot dangling in the …

July 6, 2011 – Review

“The Art of Narration Changes with Time”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

The end of the 20th century witnessed an explosion of interest in narrative practices. Often referred to as “the narrative turn,” this new field of inquiry originated in French structuralism’s general approach to language, and more explicitly from Tzvetan Todorov’s passion for what he termed “a science of narrative,” la narratologie. Postmodernism itself was a “narrative turn,” in which a rekindled interest in the fictive, the chronicle, and the anecdotal upstaged the symbolic unity of high modernism.

Narrative practices should not, however, be confused with language practices, the constituency conceptual art laid claim to, which for the most part limits the usage of language to a designative function. Or rather: it’s not language that matters, but what you do with it that counts.

Postmodernism also entailed a major shift from the political to the personal, and narrative practices are thus intertwined with a preoccupation with biographical inquiry and individual identity. In “The Art of Narration Changes with Time,” curated by Gigiotto Del Vecchio, all the works have a rickety resolution in common, signaling their self-made quality and the haphazard nature of the I.

The exhibition opens up with Klaus Weber’s Bee Paintings (2011), bright-white canvasses splattered with bee waste, positioned at random all …