Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

May 20, 2022 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

In the local elections held the week before London Gallery Weekend, the residents of Westminster City Council, which covers much of central London, voted Labour into a majority for the first time since the council’s creation in 1964. The vote was partly informed by the Conservative council’s misguided decision, widely publicized in 2021, to spend six million pounds on the “Marble Arch Mound,” a twenty-five-meter-tall astroturf hill and viewing point designed to lure viewers back to the city’s busiest shopping district. It failed: many stores are still covered with for-rent signs, one of which peddled a “blank canvas for new ideas.” These are the visual and linguistic relics of the before-time: they represent old ideas of urban environments and their inhabitants’ habits, and beg the question, “What if we don’t want to return to how things were?”

At Emalin, Augustas Serapinas is displaying eight large black reliefs made of roof shingles taken from a wooden house from his home country, Lithuania. Many of these traditional architectures are now abandoned or destroyed and used for firewood. Serapinas bought one, broke it apart, charred its roof shingles, and repurposed them into monochromes that are part-painting, part-sculpture. They are heavy, loaded with their …

November 4, 2021 – Review

Hurvin Anderson’s “Reverb”

Kevin Brazil

The first painting you see on entering Thomas Dane’s white-cube gallery—one of the two Duke Street spaces devoted to Hurvin Anderson’s “Reverb”—is called Skylarking (all works 2021). In a two-meter tall canvas, three small figures stand in the lower foreground. A woman, to the left, looks away from the viewer. Another, in the middle, looks to the right, partially obscuring the face of a man standing behind her. Are they looking at one another? Conversing? Above loom palm trees in bursts of dark green, aquamarine, and lime—above, albeit only on the surface of a canvas. The size of the trees in relation to the diminutive figures makes it hard to situate both in a coherent three-dimensional space, one which further dissolves in the lower half of the canvas as the paint thins into long thin drips. In their frozen interactions, and in their relationship to the trees, these figures are at once proximate and distant; almost touching, yet floating in unarticulated space.

This sensation of proximity and distance is produced by all the paintings in this show, even when, as is more common, no human figures appear. Each work, rendered in oil, depicts a hotel complex in northern Jamaica, where Anderson’s …

June 28, 2021 – Feature

London Roundup

Orit Gat

It would be impossible to think about London’s first Gallery Weekend in early June outside the context of the slow re-emergence from lockdowns. I know this strange sensation is not unique, but the experience of a public disaster dealt with largely by isolating from society has also marked the way I look at art. Taking stock of my tour of the city, it strikes me that the artworks which affected me most were ones that displayed intimacy, proximity, and all those daily exchanges from which I have felt distant these past sixteen months.

That is not to say that the daily and intimate are not political. At Lisson, “An Infinity of Traces,” a group show curated by Ekow Eshun, focused on the work of UK-based Black artists. It included Alberta Whittle’s video Between a Whisper and a Cry (2019), which explores Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite’s idea of an oceanic worldview in the aftermath of the Middle Passage, and a series of watercolor text drawings by Jade Montserrat (who also has a solo show at Bosse & Baum in South London) that bear heavy, physical messages, like The smell of her still burning hair (2017). When I was trying to …

January 29, 2020 – Review

Bruce Conner’s “BREAKAWAY”

Jeremy Millar

The work of the American artist Bruce Conner—dime-store assemblagist, quick-splice cineaste—is too little seen in the UK, and so we should be grateful to Thomas Dane Gallery for their recent periodic exhibitions of his work, each focused on a single film. Following CROSSROADS (1976) in 2015 and A MOVIE (1958) in 2017 comes BREAKAWAY (1966): three films from three different decades. Their achronological presentation seems appropriate, given Conner’s fascination with the temporal shifts which film afforded him.

While BREAKAWAY shares some of the concerns of these other films—such as the destructive impulses of desire and the emptiness that lies at the center of things—it is in many respects the simplest of the three. It is also the only one made from footage Conner shot himself, rather than material found from other sources. The location was a collector’s house in Santa Monica. Conner’s friends, the actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper, held the lights, and the subject was Antonia Christina Basilotta, a young singer and choreographer whom Conner had met through Stockwell and artist Wallace Berman. The five-minute film opens with a flickering image of Basilotta posing against a black background, dressed only in a black bra and black tights …

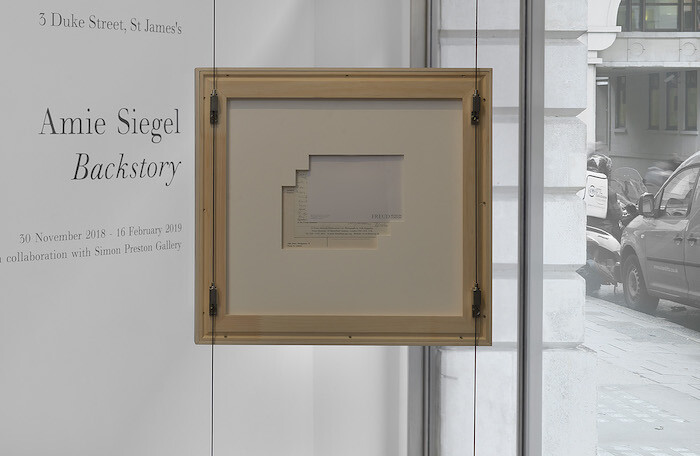

January 25, 2019 – Review

Amie Siegel’s “Backstory”

Filipa Ramos

Continuously reappearing throughout the French version of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris [Contempt], Georges Delerue’s melody Thème de Camille is the epitome of contained tragedy. Composed for a string orchestra, it has a regular, continuous motif traversed by arpeggios in counterpoint. This combination creates an immensely pleasurable (and sad) tune that flows back and forth, like the player’s hand bowing across the cello’s strings; like the calm Mediterranean summer sea waves that surround the Casa Malaparte in Capri, in which the central moments of Le Mépris take place; and like Amie Siegel’s elegant and sharp exhibition “Backstory,” whose interplay of absences and presences pay tribute to a fundamental knot of twentieth-century Western film culture.

“Backstory” honors its title. Through a set of paper works, “Body Scripts” (2015), and two video installations (Genealogies, 2016, and The Noon Complex, 2016), the exhibition gravitates around Godard’s stunning depiction of the collapse of a marriage between a submissive screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his loveless wife (Brigitte Bardot). Remaining close to Siegel’s ongoing inquiry into how value is achieved and generated and her interest in the meta-reflexivity of cultural production, the show brings forward a set of literary, cinematic, and pop-culture references that contextualize and …

July 18, 2018 – Feature

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow”

Isobel Harbison

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow” is an exhibition of works that come from a past that was alive to the future. Initiated by Mexico City’s kurimanzutto, held across the two spaces of London’s Thomas Dane gallery, and curated by Isobel Whitelegg, the exhibition echoes the interdisciplinary alliances of its subject matter: London gallery Signals’ activity between 1964 and 1966. As well as being a commercial entity, Signals was also an innovative project space, an experimental publishing endeavor, and a loosely associated set of artists primarily active between the UK (London and various regional centers) and Latin America (Venezuela and Brazil, primarily).

Both moderately sized spaces are dense with works, 42 in each. But an absence of durational work (with the exception of Gustav Metzger: Auto Destructive Art, by Harold Liversidge [1965] and Free Radicals by Len Lye [1958–79], shown consecutively on a monitor, on loop) and the careful editing of archive material (there’s a vitrine of editions near the entrance and, further into the gallery, a bench/table structure featuring excerpts from several publications), means that navigating through it is not an overwhelming documentation-heavy endeavor. There are no wall labels; the works are not divided by medium, geographical origin, theme, …

March 18, 2015 – Review

John Gerrard’s “Farm”

Adam Kleinman

Behold: a red headband-wearing cat warrior brandishing a gold-plated .45 automatic astride a rearing white unicorn that breathes fire; all this in front of a rainbow, some violent explosions, and a castle from Super Mario. No, this isn’t my fantasy, it’s simply a Google image search return for “what does the internet look like.” If I were on some strong psychotropic drugs, an auditory hallucination might have ensued stating how the depiction was “like the new Napoleon Crossing the Alps.” Although I am stone sober, that doesn’t mean that I will not now trip out.

Just as my above association might make the eighteenth-century painter and propagandist Jacques-Louis David turn in his grave, I tend to cringe when I hear the term “post-internet art.” Particularly because most of the work sold under such a label has more to do with tried and true techniques of collage, appropriation, and de rigueur concerns of cultural capital than the ever-growing macro politics of planetary-scale computation. In actuality, post-internet art’s instant popularity probably stems from the trend’s familiarity to older styles, a sort of Pictures Generation 2.0 seamlessly dragged to market to perpetuate the kind of subjectivity-building exercises that the philosopher Gilles Châtelet dubbed as …

January 17, 2014 – Review

Akram Zaatari’s “On Photography People and Modern Times”

Shama Khanna

In his latest exhibition, Akram Zaatari offers a way of reading images collectively by looking at the lives and motivations of the photographers who made them. Assuming the role of curator, the artist selects photographs and materials from the Arab Image Foundation (AIF)—which he co-founded with Walid Raad and others in Beirut in 1997—and exhibits them alongside video recorded testimonies of the photographers themselves.

The project’s primary focus is on the archive of photographer Hashem el Madani, as well as Studio Sheherazade, which el Madani established in 1953 in the Southern Lebanese city of Saida, Zaatari’s hometown. A short interview with the photographer is part of the first installation On Photography People and Modern Times (2010), which includes a two-channel video. On one side, an AIF archivist is filmed in stop-motion as she handles materials from the collection; on the other, the photographers tell the stories behind the images. El Madani, whose father was Sheikh, explains that only after checking that photography was not a sin was he able to support his son’s choice of profession. Other interviewees from Cairo, Alexandria, and Jerusalem discuss their individual relationship to photographic practice: a wedding photographer remembers scolding young brides for letting curls fall …