When the School of Visual Arts suspended in-person learning in March 2020 as cases of Covid-19 spiked in New York, provost Christopher Cyphers wrote to instructors who were migrating their courses to online platforms: “I recognize that we are asking you midway through the semester to rethink how you teach.” For the school’s MFA Fine Arts program, this was an understatement. The School of Visual Arts was founded on the idea of having professional artists instruct and advise emerging artists in a hands-on environment, and the MFA Fine Arts program has carried out this mission through one-on-one mentoring by a faculty of celebrated contemporary artists; studio visits from guest artists, curators, and critics; weekly guest lectures; peer critiques; and field trips around New York to artist’s studios, galleries, and museums. The simulacrum of this education on a computer screen, it seemed then, would be no match for gathering together in a physical space. MFA students make art, and while some mediums, like digital photography, single-channel video, or sound, lend themselves to online presentation and exhibition, the physicality of paintings, prints, and sculptures would have to be imagined. The nonverbal reactions of advisors and peers, the silent moments in which an artist can experience their work being seen, would be lost in a video conference. Concerns about how the department would function under pandemic restrictions, however, underscored what the program has sought to do: prepare artists for a lifetime of art-making within the context of an ever-changing art world.

In his 2009 essay “Education by Infection,” Boris Groys describes art programs as retreats from the world, safe spaces in which students are free to learn without the intrusion of everyday problems:

Paradoxically, the goal of this isolation is precisely to prepare students for life outside the school, for “real life.” Yet this paradox nonetheless is perhaps the most practical thing about contemporary art education. It is an education without rules. But so-called real life, where we are subject to an endless variety of improvisations, suggestions, confusions, and catastrophes, is also finally without any rules. Ultimately, teaching art means teaching life. 1

This quality of art education tracks with the evolution of contemporary art, as Groys writes: “Modern and contemporary art understands life as being ever changing, as a flow, as a process to which the individual should be permanently adjusted because this process is dangerous to anyone unprepared for change.” 2 The move to online learning became the school’s only safe option to maintain continuity for the semester. Demonstrating a permanent adjustment to change, the transition enhanced a value intrinsic to the culture of the MFA Fine Arts program: a willingness to rethink how things are done in order to ensure that an artist continues to thrive, even in unpredicted circumstances, or in this case, a plague.

Artist and long-time SVA faculty member James Siena echoed Groys. “I think MFA programs are basically a kind of professional life with training wheels. I’m constantly telling my students, M-F-A. Master of Fine Arts, okay?” Siena said. “You’ve got to rise to the occasion. Whatever obstacles are in your way, you have to continue to do your work.” As New York went into lockdown and SVA shuttered its buildings, students collected or documented whatever work they had in their studios before setting up makeshift workspaces at home, and faculty figured out the most productive ways to move learning online. To make his critique classes possible on Zoom, Siena told his students, “You will learn to document your work. You will learn to present it, and the discussions will be different.” The task proved beneficial in unexpected ways. “Students had to take really good pictures of their work, take pictures at angles to show the dimensions of the work, the physical attributes. I was impressed, and the students actually loved the class.” Photographing their work to discuss documentation and its effect on perception not only buffered the awkwardness of presenting on a computer screen but allowed students to reconsider their work through the lens of a camera. As museums and galleries scrambled to create online “viewing rooms” in spring 2020, Siena’s requirements pressed students to consider how objects made in their studios might exist in virtual space. The pandemic brought new considerations to the subject at hand for other classes in the program. The seminar “Remote Viewing—Discussion and Production of Art for Virtual Spaces” examined time and virtual space as elements for producing works that can be experienced through a screen, and “Art After the Internet” focused on the “troubled relationship between contemporary art and the Internet.” The class description of the latter noted, “Wild speculation, a suspicious attitude toward anything presented in class, and thought sharing is encouraged”—an invitation that recalls the fundamental ideas that artist Mark Tribe brought to the program when he was appointed department chair in 2013.

Opening reception for “Cocoon,” an exhibition of work by SVA MFA Fine Arts students, at New Collectors Gallery, October 28, 2021.

“Something I had to learn as chair is to be open to other approaches,” Tribe said as he reflected on the underlying culture he wanted to create. “It was really important to me in thinking about diversity. Diversity of identities is really important; diversity of cultural backgrounds, gender identities, race and culture, ethnicity—but also diversity of approaches to making.” Making art is the chief concern of the program, and students are encouraged to be as prolific as possible during their stay, to experiment and to take risks, and to bring work to completion. In generating a lot of work, they are able to receive a wider range of feedback, which may clarify their intentions or send them in new directions. Though some students approach their work in a conceptual manner, beginning with ideas and moving into physical manifestations, others make art more intuitively, responding to the play of a medium or the serendipity of process. All are welcome.

This widening of possibilities mirrors what Tribe sees happening in contemporary art as a whole. “I feel like we are living in a very inclusive and pluralistic moment. I mean, the art world is extremely eclectic,” Tribe noted. “It’s really hard to identify movements or even major global tendencies in the way that one, I think, probably could in the sixties and seventies, and not just in retrospect. It seemed very important to me in thinking about what MFA Fine Arts at SVA ought to be, that it should not take a position, that it should be inclusive—that what actually makes sense today is to create a space where lots of different positions are welcome and where people have the ability to explore them. Students don’t have to pick a side.”

A self-described interdisciplinary studio program, the MFA in Fine Arts is a draw for students interested in developing more fluid approaches in their own practices. More than following the academic trend to cross-pollinate curricula, in the program there is a department-wide acknowledgement that an interdisciplinary approach taps into ideas at play in the broader world of contemporary art. Unpacking the notion of disciplines as boundaries that contain different mediums and different artists, Tribe said, “It’s not like we’re trying to let people hopscotch between and among disciplines, but I think, actually, disciplines are artifacts of institutions, museums, and academia, and that in fact artists tend not to be disciplinary. I think we’re also in this kind of ‘post-disciplinary’ moment when lots of artists are working between and among many, many disciplines and mashing them up.” During their time in the program, students determine the directions they want their work to take, and while faculty are on hand to help and guide, there is decidedly no right or wrong way of doing things. As Tribe clarified, “The interdisciplinarity comes from the environment and the freedom—the fact that nobody is telling you to keep doing what you’ve been doing before because that’s what you’ve been doing.”

The emphasis on interdisciplinarity and a diversity of approaches is borne out in the work. Dulce Lamarca, who graduated in 2020, developed her thesis around the concept of liminality, staging a series of filmed and photographed durational performances that included tuning a cello on a subway platform for a performance that never takes place and placing a clock in her freezer. She extended her work into interactive events with an improv troupe and an audience that she assembled in her studio, culminating in a video installation that included a live screen-sharing of her desktop on which she opened Giphy, YouTube, and Wikipedia pages while typing onto sticky notes. Jay Elizondo, also of the 2020 class, created a thesis that combined archival family photos and journals scanned and altered by the artist in a performance, film, and installation made from found objects—a can of Pledge, a pack of Marlboros—enhanced with sequins and crystals.

“Media boundaries have become more fluid,” agreed photographer and faculty member Accra Shepp. “I don’t want to say crumbled, because they still exist, but there’s a kind of dialogue that’s going on now that wasn’t present, say, twenty years ago, or it was much less so twenty years ago. And the department is really riding that wave.” When Shepp first considered teaching in the program, the idea of working with students across mediums using his own studio practice as a starting point appealed to him. “Mark saw that I was interested in how people voice themselves through objects and things that are visible,” he said. “That’s what I’m really interested in, and that’s what everyone here is interested in. Now, we all have our own points of view that are part of the disciplines that brought us to this point, but none of us feel that it’s a privileged position and one that you can’t arrive at in any other way.”

In addition to Siena, Shepp’s colleagues include such art world luminaries as Rico Gatson, Gary Stephan, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Dread Scott, Marilyn Minter, Kenji Fujita, Miguel Luciano, Ei Arakawa, Dara Birnbaum, and Mika Rottenberg—artists who are all actively engaged in their practices—as well as art writer Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, art historian Media Farzin, and curator Jasmine Wahi. While some instructors teach every semester, others may lead short seminars or teach only one semester each year. The diverse faculty consists of thirty-nine professionals who visit the program’s sixty-six students in their studios each semester. Weekly talks by guest artists and art historians; field trips to artists’ studios, museums, and galleries, often in the school’s Chelsea neighborhood; and faculty-led peer critique classes round out the curriculum, allowing students to build a broad community of advisors and collaborators over the course of four semesters. Each student is matched with a faculty mentor for two years, but students can also request to meet with any other instructor as well.

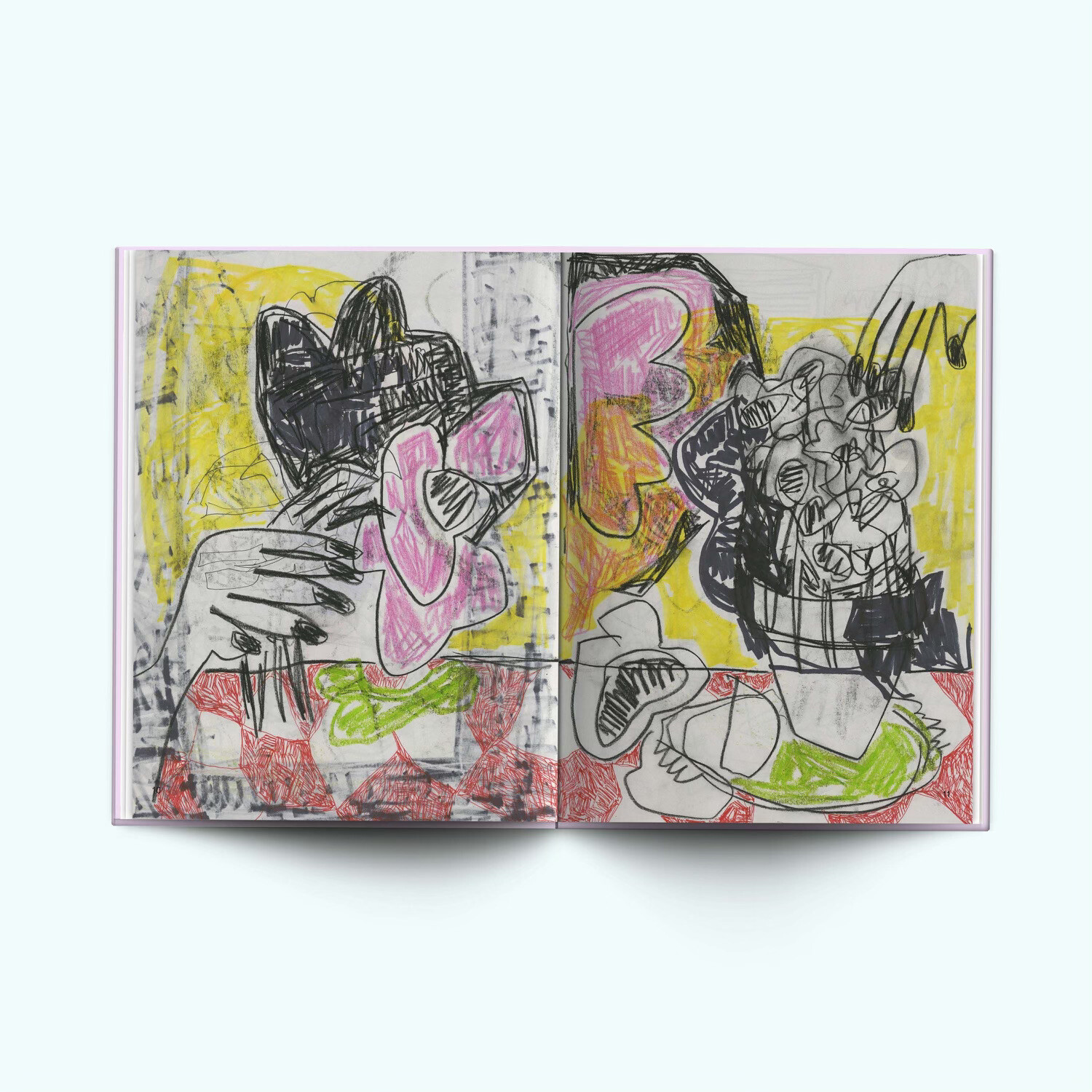

Access to professional artists—artists who have an ongoing practice and who exhibit and bring work to market—also means students can seek advice beyond the specifics of what they are making in their studios as they prepare to build careers and navigate the art world. To this end, the program offers participatory workshops on building relationships with galleries, the legal considerations of art sales, and applying for grants and fellowships, during which students work on statements and portfolios together. Siena teaches a two-part workshop titled “On Presentation and Completion—It’s a Time Machine (If You Want It)” that intends to address “uncertain resolutions springing from unfinished works and thoughts” that might hinder artists from fully bringing work to completion and moving it into the world. Another workshop deals with documentation, an important consideration for students creating temporary, site-specific work using ephemeral mediums. Semester-long seminars are based on the personal interests of individual faculty members, ranging from art history and critical theory to making art in the Anthropocene and intersectional feminism. Whether bringing into the classroom a lifetime of experience in the studio, or updates on new developments in the art world at large, faculty members aim to nurture the students’ individuality as they embark on careers as professional artists. For instance, when Dylan Rose Rheingold, a second-year student in the class of 2022, had an exhibition at Selenas Mountain gallery in Ridgewood, Queens, this fall, faculty member and renowned artist Gary Stephan and his partner, artist Suzanne Joelson, went to see the show and talk with her. Stephan admired Rheingold’s sketchbooks and her idea to make a book, and so she sought out Catastrophe Media and Crosstown Press, both small, women-owned, independent publishers. The resulting publication, A Line of Thought, is a limited-edition collection of her drawings and works on paper, for which Stephan wrote the introduction.

“It’s in the DNA, it’s in the curriculum,” Tribe said of the program’s commitment to career development. “This is preparing people to hopefully be professional artists, wearing many hats in a very precarious and fast-changing art world.” This may mean participating in the market in exhibitions, but it could also include entrepreneurship and creating nonprofit, for-profit, or artist-run exhibition spaces. Emerging artists might also turn to publishing or teaching. There is talk around the department of minting NFTs. The aim is to help students build pathways to whatever microcosm of the New York art world will best serve them by giving them both the necessary skills and the confidence to seek out opportunities while they are still in the program.

Case in point: first-year student Camila Varon Jaramillo, excited to get things moving, worked with two friends this fall to organize “Flow,” an exhibition of their work. A real-estate agent told them about a space on Ninth Avenue that could be rented for a few weeks, which prompted them to mount a pop-up show of their paintings, hiring an ice cream entrepreneur to cater an opening that was well attended by friends and peers. “That’s the kind of thing we really encourage our students to do,” said Tribe. “While you’re waiting for someone to invite you to do something, go ahead and, you know, grab the bull by the horns and leap.”

Finding support beyond the two years of the MFA is typical of the program. Tribe leads a seminar called “White Cubes” in which students organize or curate weekly visits to galleries, nonprofit spaces, and museums. Last spring, his class visited FiveMyles, a nonprofit exhibition and performance venue near the Brooklyn Museum. When FiveMyles contacted Tribe about a summer performance program, he recommended Dulce Lamarca, who was working as his studio assistant after graduating in 2020. A few months later she was performing Solid Drift in the gallery, a work that featured spoken word, cello, and video projections in collaboration with two other artists. The program also encourages students to build a community that will remain in place after they graduate. “I stay in touch with the students for as long as they choose,” said Shepp. “I tell most of them to feel free to drop me an email if they have a question or need something.” Students occasionally ask him for recommendations or let him know if they have an upcoming show. “I think just knowing that they can be in touch with somebody is important, that they’re not by themselves, even when the program is finished.”

A small kingdom within a larger art school, MFA Fine Arts offers students access to many of SVA’s amenities, such as video and photographic equipment, ceramic and textile studios, a printmaking lab, a risography lab, and the school’s bio lab, where specimens, skeletons, plants, and aquatic life are available for art-making. Many take advantage of the digital fabrication lab, which allows a level of precision that previously would have required outsourcing their work to wood or metal shops. Tribe reported an uptick in the use of virtual reality, with the department providing headsets, PCs, and other necessary equipment. Augmented reality—for example, using an iPhone app to access more information or trigger an experience within a work—is also gaining popularity among students. Faculty member Rico Gatson stressed that students need not bend to the trends of the current moment at the expense of their work, but should consider how evolving technologies and traditional mediums may best serve their ideas at present and in the future. “It’s kind of a balance,” he noted, “because I think that you have to negotiate the tools that are the times, but you don’t have to give up everything. It’s still okay, as far as I’m concerned, to embrace that sort of sincerity and beauty, otherwise it’s just too jaded.” Alongside deep dives into cyber experiences, more tactile work like painting, printmaking, and working in clay continues. An interest in the urban environment remains strong, with students collecting detritus along the city streets to use in sculptures and installations.

For second-year student Xayvier Haughton, the retreat Groys described amounted to logging into last year’s courses from his home in Jamaica. But with New York City “reopening” some eighteen months after restrictions were put in place, SVA has optimistically returned to full in-person learning. Arriving in town the week before the start of the semester, Haughton was still acclimating to the city, trying to find his place in his new surroundings. “There’s a whole lot of buildings, a lot less trees,” he laughed. “I’m trying to soak up the environment, just allow it to inform me without losing that thing that makes my work mine.” Haughton creates installations from found objects—beer bottles, coins, discarded cutlery. Alluding to his work, he joked, “I feel like there are materials on the floor, just on the street, laying around.”

Tribe and his faculty and staff are equally excited about the change to in-person learning. He noted that this is not a return to the old, but a new chapter for the program, and he is hopeful it will be a happier one. “The keyword here is ‘embodiment,’” he said. “It’s not so much about recovering something that was lost as just really enjoying physical presence with one another and with what we make.” Remote learning, he said, “works remarkably well in a mediated way, but there’s something to be said, something ineffable, about direct, unmediated experience and embodiment, being together in real space at the same time, that is really powerful. I think there’s just more looking forward to being able to do that in-person, being together in the same space in the same room.”

On an autumn evening, the warren of studios that take up the eighth floor of the school’s West Twenty-First Street building was bustling with students. One person rolled white paint across the floor and walls of their studio. A few doors down, another student rubbed a charcoal pencil back and forth across a large sheet of paper. Some students sat at folding tables, looking at their laptops. The space was silent, save for the quiet rhythms of artists at work. In some ways, things had returned to normal, but only inasmuch as life has returned to normal in any other domain. In the uncertainty of what may or may not be the beginning of a post-pandemic time, the students face a new set of questions regarding the purpose of art-making. Tribe defined them this way: “What’s really important to me? How do I want to be spending my time? It’s a really good set of questions for artists to be asking.”

Boris Groys, “Education by Infection,” in Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century), ed. Steven H. Madoff (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009), 27.

Ibid., 28.