Éric Baudelaire: To Do With

Tickets

Admission starts at $5

December 2–5, 2021

172 Classon Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11205

USA

e-flux Screening Room at 172 Classon Avenue in Brooklyn will open on December 2, 2021 with To Do With, a four-day program presenting a selection of films and films-in-progress by Éric Baudelaire, in dialogue with works by Chantal Akerman and Naeem Mohaiemen, and followed by conversations with special guests Omar Berrada, Stuart Comer, Dennis Lim, Naeem Mohaiemen, Paige Sarlin, and Kaelen Wilson-Goldie.

Tickets for the program are available here.

The program is organized with the support of Villa Albertine, in partnership with the French Embassy in the United States.

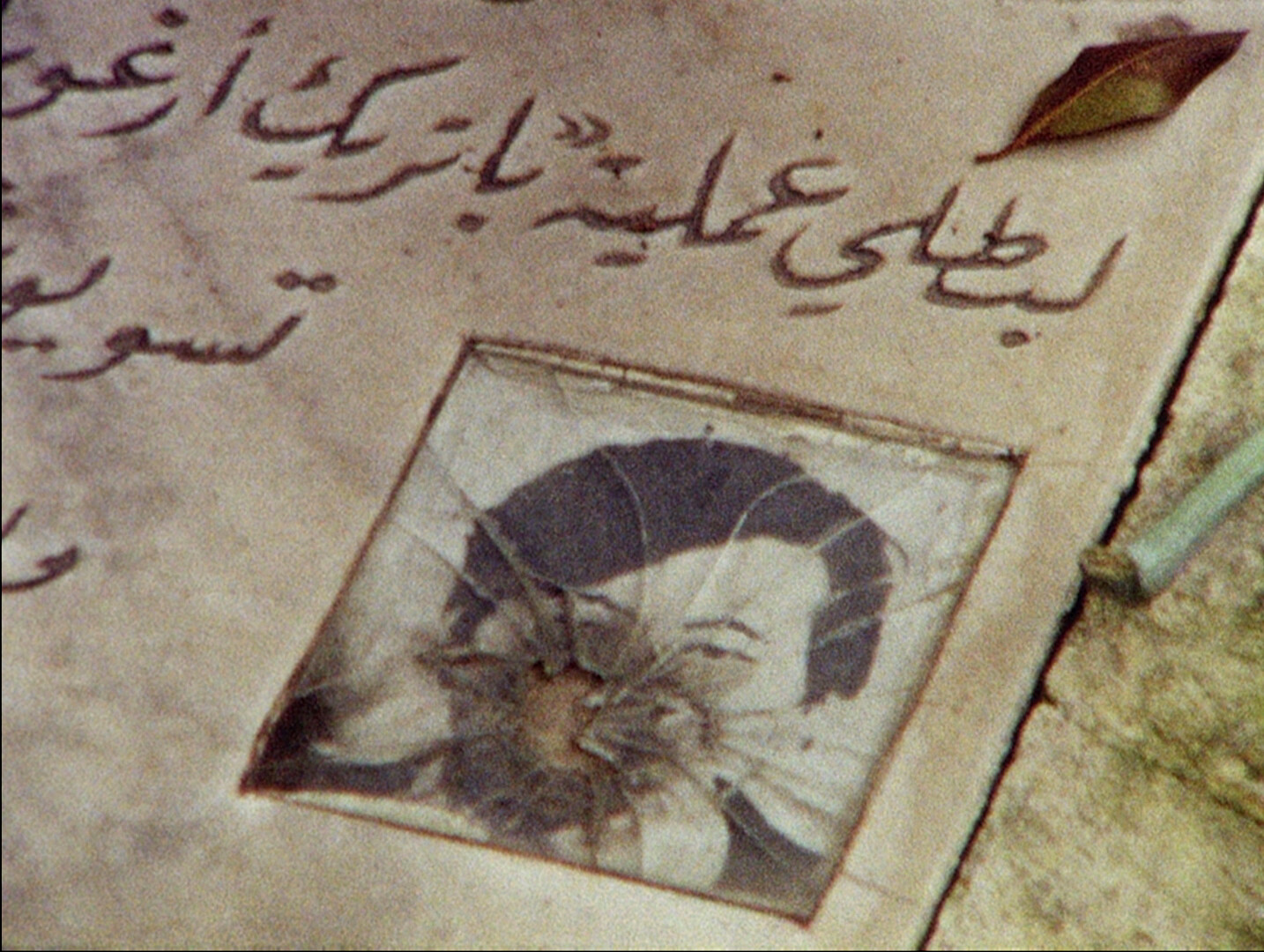

Merging traditions of documentary, experimental, and fictional filmmaking, Éric Baudelaire examines processes that shape the conditions of today’s reality. Trained as a social scientist, for the past fifteen years Baudelaire’s films have explored historical setbacks and invisible mechanisms of power. Choosing to explore subjects that do not generate consensus, Baudelaire often undertakes dangerous cinematic journeys with no preconceived conclusions or scripted outcomes. His cinema can be understood as a processual practice of posing difficult questions that have no simple answer, or no answer at all. The desire to search for the reasons behind the incomprehensible and invisible side of our reality can be traced throughout Baudelaire’s entire filmography, a selection of which will be presented in e-flux Screening Room: his short The Glove (2020) in which a rubber glove wanders through a city under lockdown; his collaboration with children-as-filmmakers in Un Film Dramatique (2019); his thwarted interlocutions with the radical Japanese filmmaker and Red Army member Masao Adachi in The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years without Images (2011); his unlikely exchange with Maxim Gvinjia, former Foreign Minister of the unrecognized state of Abkhazia in Letters to Max (2014); and his revisiting of Adachi’s landscape theory via an unseen, contemporary protagonist in Also Known As Jihadi (2014). The films are presented in dialogue with two other films that have been important in Baudelaire’s practice: Naeem Mohaiemen’s United Red Army made in the same year as The Anabasis… and recounting the infamous 1977 hijacking of Japan Airlines Flight 472; and Chantal Akerman’s D’Est (1993) which, like Letters to Max, grapples with a contested Western gaze towards the East. In a special discussion session, Eric Baudelaire will also present his two current works in-progress: When There is No More Music to Write exploring how composer Alvin Curran’s life and work intersect with the radical political movements emerging in Italy and around the world during the 1970s, and the film dyptich A Flower in the Mouth, a poetic reflection on ever-approaching catastrophe, flowers, and the human gaze.

We invite you to join us for this program introducing his practice through his own words and films, in dialogue with interlocutors and films in close proximity to his work.

To Do With

Éric Baudelaire

A literary critic once asked me whether any books had influenced my decision to become an artist. I answered Libra by Don Delillo, read in 1995 while conducting research on the Cuban Missile Crisis at the Kennedy Library in Boston. My job at the time was to compile a minute-by-minute chronology of all that took place at the White House during those thirteen days in October 1962 when the world hovered on the brink of disaster, and to transcribe newly released audiotapes recorded secretly by Kennedy in the West Wing. Who were the President and his brother Robert meeting with? What documents did they consult? I learned to recognize each cabinet member’s voice and to decrypt aerial photographs of Cuban landscapes in search of clues about what they knew. The professor I worked for was revising a classic political-science textbook that sought to fine-tune models of decision-making in times of crisis. As for me, the more meticulous my research and the more detailed my chronologies got, the more aware I became of the importance of chance, or rather of luck, through those days when humanity narrowly escaped nuclear Armageddon. I lived in Somerville, working from home through a heat wave while a fan blew papers across the room. Each night, I returned to Don Delillo and the crystal clarity of his fictional characters’ intrusion into the opaque narrative of the Kennedy assassination. His writing neutralized the question of what was real and left me floating pleasantly in its own sense of time, place, and circumstance—a continuity that would elude me the next day as I sifted through stacks of archives, trying to make out the voices of John and Robert on a tired magnetic tape.

Later on, I asked the literary critic what he was reading these days. He told me that he had been unable to get through a single novel for two years. He spoke quietly and deliberately, catching his breath between sentences. He had been wounded gravely, losing part of his face in the Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris in 2015, and had undergone many rounds of reconstructive surgery. He told me that in all his time in and out of hospitals he had only been able to read non-fiction books, aside from a few fragments of previously read classics illuminating or thickening the mystery of his own experience. For now, he has said farewell to novels. He told me, “Imagination remains, no doubt, a necessity, but it has become a luxury that I no longer have access to. It has also become a threat to the future.” Then he used an expression I do not know how to translate, referring to his imagination: la folle du logie dont il fallait se mefier—the crazy lady of the house you must watch out for.

I never encountered a useful definition of what the real is, but I have always had a great love for those who strive to grasp it, to study its mechanisms, or simply to illuminate a fragment of it, so that we can reflect upon it with different measures of invention, imagination, and observation.

A passage from Samuel Beckett comes to mind: “there will be a new form and (…) this form will be of such a type that it admits the chaos and does not try to say that the chaos is really something else. The form and the chaos remain separate… That is why the form itself becomes a preoccupation, because it exists as a problem separate from the material it accommodates. To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now.” Today, the word mess and the word real seem almost interchangeable. What matters to me about Beckett’s formulation, what feels necessary and urgent and relevant is that it doesn’t speak of a task to reveal the mess, or to deconstruct it—we have done much of this work already. It speaks of a need to accommodate it in a form, so that we may find new ways to relate to it, whatever that form may be.

In my films I am interested in characters who struggle with the real (rebels, secessionists, teenagers), who try to reshape it, and who sometimes go astray. In searching for a form, I have often woven into my films traces of my own entangled relationship with their subjects—through a correspondence, an exchange, or simply through camera movements that translate my hesitation in this search for an appropriate form. To echo the questions raised by the process of making the film, I often feel the need, once the film is finished, to search for expanded forms beyond the projection itself, to bring together other films and other artworks into the exhibition space, to publish booklets with detailed chronologies, to organize discussions with the public and guests from various fields of knowledge.

Thinking about the real today, and more specifically about a cinema that searches for new forms to accommodate it, reminds me that a form can create a community of circumstance. A community that exists because of the form, a community that thinks about problems that the observed real poses. What matters is experiencing a sensation together, experiencing a non-fragmented continuity together. Thinking anew our sense of time as we reflect on the mess. To rethink, with urgency, our experience of time.

Program

Part Six

Artist Talk and films-in-progress: Éric Baudelaire, When There is No More Music to Write and A Flower in the Mouth

Conversation: Éric Baudelaire and Stuart Comer

December 5, 2021, 6–8pm

Part Five

Screening: Éric Baudelaire, Also Known As Jihadi

Conversation: Éric Baudelaire and Paige Sarlin

December 5, 2021, 2–4:30pm

Part Four

Screening: Éric Baudelaire, Letters to Max

Conversation: Éric Baudelaire and Omar Berrada

December 4, 2021, 5–7pm

Part Three

Screening: Chantal Akerman, D’Est

December 4, 2021, 2–4pm

Part Two

Screening: Naeem Mohaiemen, United Red Army and Éric Baudelaire, The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years without Images

Conversation: Éric Baudelaire, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

December 3, 2021, 6–9pm

Part One

Screening: Éric Baudelaire, The Glove and Un Film Dramatique

Conversation: Éric Baudelaire and Dennis Lim

December 2, 2021, 6–9pm