Birthing me at the age of forty-two almost killed my mother. A midwife was by her side, however, at the hippie birthing home. And at the critical moment, this doula realized that this particular job was not going to be a case of “catching babies” (a popular industry definition of midwifery). She fetched a doctor, who saved both our lives—Mum’s, and that of the fetal pre-version of me. This occurred just over three decades ago, in Austria. Today, I live in the United States, and I can happily say that I count midwives—birth doulas, death doulas, abortion doulas, and finally, full-spectrum doulas (who blend all three)—among my friends. I even briefly met my lifesaver, my parents’ midwife, on a trip to Vienna years ago.

The word “midwife,” at its Middle English root (mit-wif), simply means “with-woman.” To be a midwife is to be a woman with, a companion to another, especially during the more slippery, amniotechnical moments of social reproduction: partum, miscarriage, departure.1 I kind of like this etymology: it suggests the art Donna Haraway calls “staying with the trouble”; a commitment to being-with, no more, no less. But modern usage, as you probably know, favors the word “doula,” because our collective preference seems to be for the apparent gender-neutrality (false, as it happens … oops!) of a word that originally meant “slave, servant” in ancient Greek (doule; δούλη)—over any word that includes that ur-gendered word “wife.” I’m not going to try to unravel, here, the co-constituting emergence of femaleness and servitude through history. For my purposes, it is enough that, demonstrably, anybody can be a good with-wife. What it takes is willingness to learn the labor of holding; staying; witnessing; facilitating the crossing of liminal thresholds; lubricating the beginnings and ends of human life-forms. The skills in question sprout up in the cracks throughout human societies, yet, under capitalism, there is next to no incentive for universalizing them. The fact of departing, or arriving, or undoing life, remains (for now) of limited market use.

How will we do birth and dying under communism? Today, training and certification in various forms of “doula-ing” is increasingly available throughout the world, as are the attendant opportunities for entrepreneurs and other capitalists to extract profit from a doula industry, which is a matter of hot ideological dispute among doulas themselves. Especially in the United States, the different subfields of the doula vocation are variously undergoing slow but sure professionalization. Yet doula-ing, as every doula I know insists, is not a profession, rather, it is an open-access verb (albeit a hideous one, at least in its gerund form). You or I, in other words, singly or as a collective, might at some point or another be called to doula the inaugural emergence, or terminal shutdown, of someone’s body. You never know when an extra hand might be required on the occasion of someone’s expulsion of a fetus (dead or living) from their uterus. You never know when your simple watchful presence might be called for because someone is dying and because, without you there, they would be utterly alone. As Madeline Lane-McKinley says, “if we must mother our friends, let us all be mothered.”2

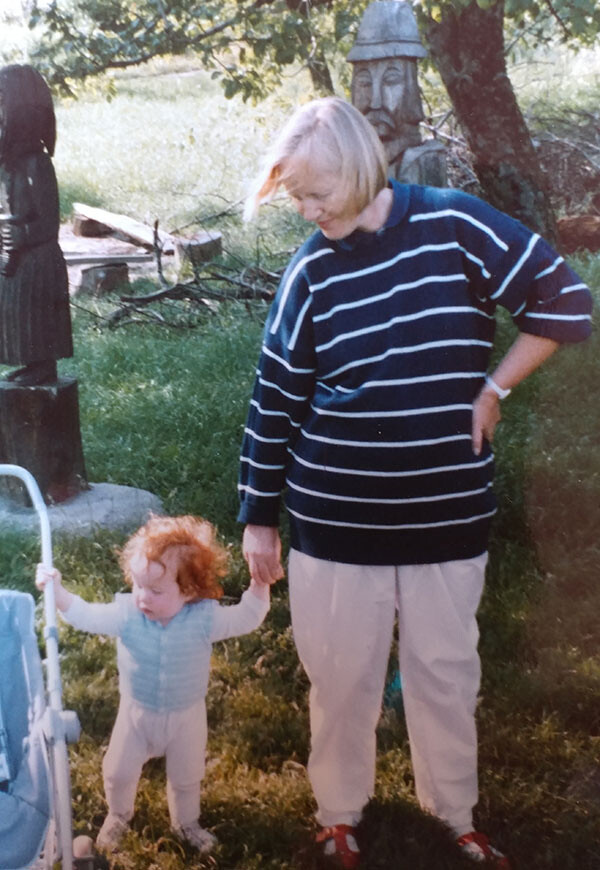

Luna, the feral Bavarian cat, who according to Ingrid Lewis was in need of resolving an attachment crisis. Photo courtesy of Sophie Lewis.

My mother was not of this mind. In 2016, she sent me the following WhatsApp:

I am trying to coax Luna out of an attachment crisis. I discovered lots of moth holes in my old pashmina so now I keep it on the floor next to my chair to wrap my feet in. I think Luna thinks the pashmina is her mummy because she’s milk-treading it all the time. :’(

To this, I replied:

Well who is to say the pashmina isn’t her mummy. Many things can be one’s mummy perhaps

There followed a pause. Finally, I receive back, in capitals:

I AM HER MUMMY. END OF

Further to which, after ten minutes of silence, there was further, hilarious clarification:

Luna says I’m her mummy, end of.

It is not quite an exaggeration to say that the entire thesis of Full Surrogacy Now—mothering against motherhood—might be glossed as an extended meditation on this exchange.

***

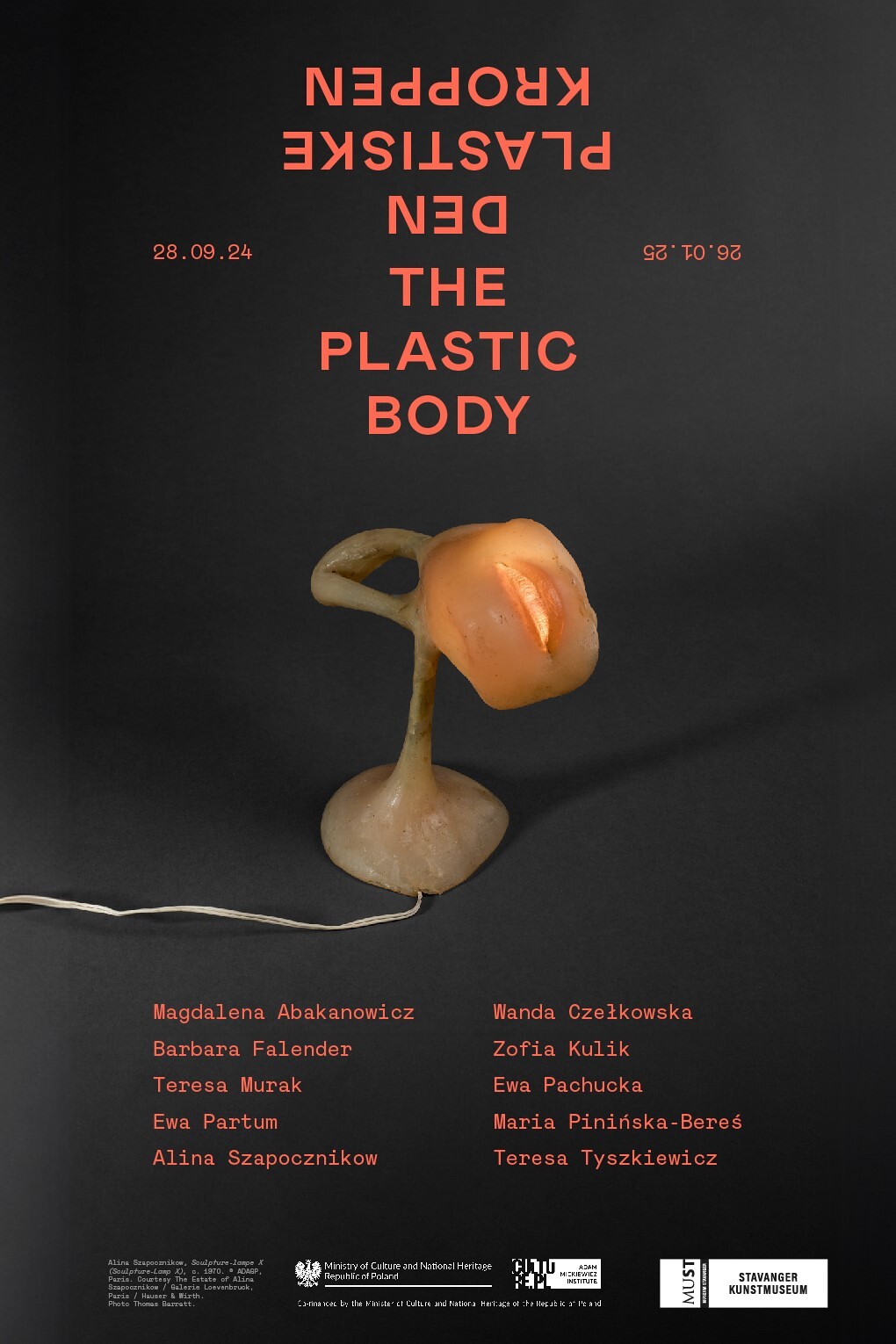

I know a little about what birthing me was like because shortly after the ordeal, my mother typed a lacerating account of it on a typewriter in her first language, German. The text positions her in the third person, like an ancient archetype: “die Frau” (the woman). The agony intensifies. The woman screams. The other members of the cast, helping her, are “die Hebamme” (the doula), “der Mann” (the man), and after things start to take a turn for the worse, also “der Arzt” (the doctor). Hebamme, by the way, comes from heben (to lift).

It isn’t just the description of my deeply non-mother-identified mother as someone who desperately wants to mother that is strange for me in reading this text. It is also simply odd to read her in German, since her West Germanness was usually another thing she—like many 1968ers of that nation—repudiated all her adult life. In the ’60s, she was a first-generation undergraduate who’d defied her parents in order to be able to study, despite her sex, at the public university in Göttingen. She joined a Maoist group and seems to have been traumatically used by a sexist, closeted professor she fell in love with prior to marrying—and divorcing—twice—another mustachioed member of the cadre. Her father had fought in Hitler’s army. Meanwhile, her maternal forebears had been Jewish, a fact Mum learned only in 2008. They were once “Sternbergs” who converted, changing their name, in order to embrace anti-Semitic Gentile life—a life carried out subliminally ashamed and terrified of discovery—some considerable time before the war. My authoritarian Opa died relatively young; and Oma, in her old age especially, was a nightmare of a person in whose presence, around her kitchen table in Hannover, I witnessed Mum, the wayward daughter, struggling to breathe. Nothing about Germany, in short, seems to have held my mother or felt worth holding onto. Inexplicable as this appears to me today, she was a profound Anglophile, enamored of Fleet Street and Dame Judi Dench. She yelled at Germans who couldn’t pronounce her new surname, “Lewis.” Living in France (which is where I was raised), she affected the airs of a vaguely aristocratic Englishwoman, albeit in a marked German accent I literally didn’t hear until it was pointed out to me in my mid-teens. And she refused to teach her kids their “mother tongue” even when they asked to be taught it.

“It Lives” recounts the story of the author’s birth, as typewritten by her mother. Photo courtesy of Sophie Lewis.

At the time of her writing of the typewritten account “Deine Geburt” (Your birth), in 1988, she had just married, on the cusp of menopause, a much younger man from England, the kind who passively believes that Earth’s greatest civilizational achievement is William Shakespeare. Much later, while propped up in the alcoholism ward of a hospital, she glued the single piece of paper onto the first page of a kind of belated baby album for me.

The text occupies the page like a solid wall. At first glance, it looks like just one enormous paragraph. Overwhelmingly, it is a recounting of endless hours of desperation (Verzweiflung) and anger at der Mann, who isn’t holding her correctly. She feels insufficiently lifted, insufficiently held. She hates and fears going forward with the task that stretches before her, through the sticky night.

Yet “Deine Geburt” culminates in an ecstasy of relief, an almost religious cry of love for the product of the birth-labor, das Erhoffte (the hoped-for one). There is a line break at the very end, and then a tiny surplus, a tadpole, a melodramatic closing clause:

Es lebt.

(It lives.)

***

As of today, I remain living still. But she, ever since late November, is dead. My mind still struggles to compute this aspect of reality, even though it was a long time coming. Over thirty-two years, we did not hold one other well. Where did she go? I still do not fully comprehend that I cannot send her a mini emoji-essay on WhatsApp. Mum herself, it has to be said, was willfully uncomprehending, to the last, of the fact that she was about to become unWhatsAppable. She did everything she could—principally, drinking—to avoid acknowledging her imminent deadness, to repress thinking or talking about it.

There was one nonhuman, however, who read the writing on the wall. After enduring months of Mum’s frequent protracted absences whenever she was hospitalized, Luna, the feral Bavarian farm cat who hissed murder at everyone who wasn’t Mum, eventually disappeared without trace from their cigarette-scented London flat.

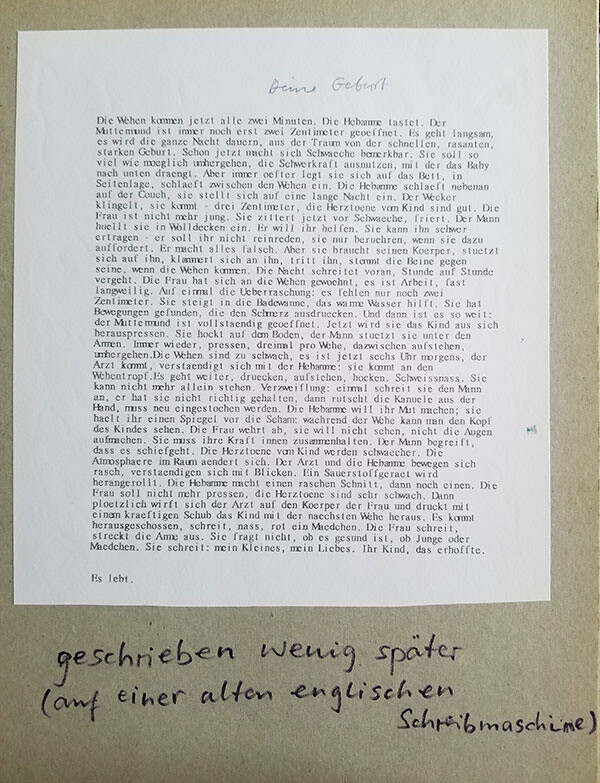

A bedridden Ingrid Lewis before Luna the cat mysteriously disappeared. Photo courtesy of Sophie Lewis.

Mum died Luna-less, therefore, at the age of seventy-three, shortly before the age of Covid-19—of more than one cancer, plus heart complications and whatever the effects were on her body of years upon years of immobility, alcohol, quasi-suicidal use of sleeping pills, not eating much or well, and chain-smoking. Following her cancer diagnosis, living as I do in Philadelphia, I made three trips to and fro across the Atlantic in 2019 while my visa status was—stressfully—in flux. Two of these trips combined time at her bedside in hospital (as she attempted to shame me by pointing out) with work, namely, gigs promoting my book.

During the one, final visit exclusively devoted to saying goodbye to her, she and I succeeded at spending some happy-ish hours in each other’s company. But one day, she attempted to bestow on me some jewelry that had belonged to her late, hated, mother. “Do you want these now, or only when I am dead?” she asked me in a tone of coquettish grandiosity, fingering the string of pearls with affected sentimentality. “Uh, I don’t know,” I stammered, full of horror at the ineluctability of these moments of dynastic bestowal, no matter how untethered the scene to any real mother-daughter intimacy, how falsely charade-like, how hitherto despised (or at least disregarded) the pearls.

“Um. After would obviously be fine … I really can’t say. Now? I guess?”

Mum received this answer, her hand poised on the brink of releasing the pearls into my palm. Then, suddenly, she snatched the necklace back.

“No! After … Hee, hee. Sorry.”

As my face had flooded with humiliation, hers had lit up with glee.

“To be honest,” I said, “I don’t want your fucking Nazi gold—”

“Tch! It’s not Nazi gold.”

—“and I thought you didn’t want it either! You hated your parents, didn’t you?”

Then she looked very tired, and I stormed out of the tiny electric-orange flat in order to make an emergency walk around a park with a friend, ashamed, hurt, disgusted, but also resolving to sell the pearls, if ever I got them, and donate whatever they earned immediately to a migrant fund.

***

Despite her being in the ongoing care of extraordinary hospice workers and of my brother (who lives an EasyJet ride away from her London flat), my mother was accompanied by no familiar presence at the time of her death other than her ex-husband’s—my estranged father, the Englishman—who happened to be visiting that day. She was, however, listening while she died to a video recording of my brother and me, singing in harmony: “Don’t you dare look out your window / Darling, everything is on fire / The war outside your door keeps raging on.” A toy lobster I had brought for her earlier in the year lay on the pillow next to her head.

It was for reasons other than the coronavirus that she got no funeral. It wasn’t a lack of money. It wasn’t an objective logistical impossibility, either, although there were seas and oceans dividing her remains from the parties who might have gathered around them. No, the lack of funeral derived from the difficult fact that Mum, who lived alone and seemed to have alienated more or less every friend ever to have entered her life, simply had nobody. No one, that is, apart from her damaged and damaging “nuclear” kin, i.e., me and Ben and our father (her ex-husband). I defy anyone to tell me that the misery such situations entail, this heartbreaking insufficiency amid good intentions, this ideological blackmail borne of the very scarcity it itself produces, is a viable model for organizing human lives. If I had not been a family-abolitionist already, I can assure you, I would have become one last fall.

Please, hear the complaint I’m about to make not merely as self-pity, but as a scream for a world in which good deaths, the arts of witnessing grief, and grieving, are taught to all children from an early age. I will not gloss over it, nor counterbalance it with something hopeful and consolatory. There was not enough doula-ing around Mum’s death. She had extraordinary hospice staff, yes, but no dedicated companion committed to seeing her over the edge. Rather, it was we, her default kin, who had to do our best at putting our selves to one side in order to perform that function. And there weren’t doulas there for us, the death doulas, either, in any kind of sufficient number. Sure enough, looking back at the situation with the benefit of five months’ worth of hindsight, it is easy to articulate this criticism about Mum’s death in the register of the “transitional demand.” More damn doulas!

Certainly the three of us would have needed a doula, or several, in order to make a public burial or cremation ceremony thinkable. Meanwhile, I am deeply, ragefully aware that many people in this world, to whose funerals masses of mourners would come, receive no ceremonies because of state violence, poverty, fugitivity, structurally produced anonymity, or prison walls. And this fact, that not every human being gets a funeral, has always been one of the major symptoms of the depravity of capitalist societies for me. Yet the fact stubbornly remains: some human beings today end up in circumstances of practical friendlessness and un-mourn-ability. This is very different from being, as my white cisgender middle-class mum was certainly not, ungrievable.

Also, it turns out, funerals don’t organize themselves. Also, it turns out, some funerals are impossible. They are impossible, for instance, because, among the three or four people who would attend them, at least two individuals cannot be in the same room together. It might be equally true, actually, to express this the opposite way: when two individuals must not be in the same room together, a certain kind of funeral is all too possible. Doula-ing is required, in those cases, to help a funeral not go ahead. In an essay by Laura Fox on filial estrangement, she writes: “Every day I have to resist the urge to reconcile with them.”3 Such individual resistance cannot prevail unassisted. We require women-with to help ourselves not-be-with. Resilience, even in estrangement, is necessarily woven together with others.

What is the antonym of doula-ing? Minutes after death happened to Mum, an up-close photo of her gaping, lifeless face was nonconsensually WhatsApped from her phone to my phone by my dad. (I have his number and email address blocked.) Seconds later, I received a notification that Ingrid Lewis, the very woman who hadn’t been on Facebook for years and who had just died, liked several posts of mine.

***

Potent and sweet, however, remains the with-womanning I have known. At the formal level, I have discovered that diverse practices of grief-companionship exist in communities all over the world, including in my neighborhood—for instance, the Philly Death Doula Collective’s grief circling initiative, whereby neighbors and strangers sit quietly and listen without comment to one another’s grief.4 It is grief itself, for Kai Wonder MacDonald, the founder of the Philadelphia grief circle, that is to be savored in its own right—not simply gotten through; or conquered; or shed as fast as possible in favor of a return to productivity.

Catching my eye, via a fly-posted flier, serendipitously soon after Mum’s death, Kai’s grief circles initially helped me understand that had I already enlisted many of my comrades as doulas in my grief long ago. What became clear only over time, however, was that it can be generous, in an odd way, to be greedy with one’s need to be held: more damn doulas! The weaving of help-seeking and witnessing, giving and receiving, seems to operate on a non-zero-sum plane in the circle of the bereaved. Dozens of us are now swimming grievingly together on Kai’s weekly or biweekly Zooms. Even before the era of coronavirus, in a work society defined by capitalist time (not to mention the opioid crisis), there was already a palpable sense of resistance in the death doulas’ power to insist on non-progress, on the possibility of nonlinear evolution and non-healing. Kai personally, in fact, led me to the realization that it was not too late to hold a funeral: that I could be a Zoom-based death doula to myself and my brother via an honest, non-euphemistic ceremony about Mum to which we could invite only those people whom we wished to invite. Kai silently attended the ceremony, which felt wonderful.

Ingrid Lewis and the feral Bavarian cat, Luna, she wished to mother at the end of her life. Photo courtesy of Sophie Lewis.

Nine months into this strange adventure that is grief-circling (now, in the Covid era, via Zoom), for me there is no question: dying is a powerful site of anti-capitalist consciousness-raising. As North Carolina death doulas Saralee Gallien and Roxane Baker put it, there is resistance in “closing the door or being like, ‘we’re not done here.’” After a death happens, “the clock starts ticking really fast.”5 The art of the mit-wif, in many ways, is the steadfast solidarity of the unproductive.

And productivity was also sacrificed, in spades, for my sake, while Mum died. More than once, my closest kith traveled from the north of England to sojourn with me in the guest room of the building whose adjacent area (lands once dense with birds, no doubt) the feral Luna was conceivably still roaming. One friend helped me by non-aggressively saying “no” to Mum’s absurd whims—something I didn’t fully realize was possible—and just patiently sitting, or physically maneuvering her in and out of things. Another vacuumed a substantial fraction of the cigarette ash from her carpets and helped me assemble, when the time came, her special electric bed; a bed that was immediately disassembled after she transferred to her hospice deathbed. Whether on WhatsApp, on Zoom, or in person, my doula-comrades simply participated. One evening, when there was an opening, a comrade knelt at Mum’s hostile feet and drew tarot cards for her, which Mum, to my surprise, loved. Month after month, they listened to my heartbreak. Judy steadfastly refused to be offended by Mum’s misogynist resentment and jealousy (“I don’t like this Judy, why is she here?”), and simply stayed, modeling acceptance, enthusiastic appreciation of—and even love for—this un-mother of mine, without ever minimizing her brutalities or culpabilities.

“Perhaps, as a result, thanks to my many-gendered with-women and my grief circle, my heart has broken sufficiently to allow posthumously for my falling in love with Mum again, the way I did when I was a baby.” Photo courtesy of Sophie Lewis.

Judy also gathered testimonies about Mum, after her death, into a Google Doc—at the top of which there is an “ode.” “In her final days, after she became unable to eat or drink, she continued to imbibe wine via a sponge on a stick”—such is the general tone. Chiefly, the Doc comprises celebratory anecdotes, such as the one about her adulterous one-night stand with what turned out to be the former prime minister of a European nation-state (a man whose nickname was “Lewd Rubbers”). Or the time she thought there were trans-exclusionary Labour Party feminists, perhaps dwelling gremlin-like in her printer, interfering with her ability to print out a pro-trans email. Or the time she was fired from a volunteer job at a charity shop for calling her manager a “fascist” on the basis that he’d asked her to stow her handbag in the staff area. Or the time she was smoking a spliff in a field, aged sixty-one, and “tipped over backwards in slow motion until she was lying on her back with her feet in the air. Puffs of smoke rising up into the night sky like a steamboat.”

Betrayal, abuse, cowardice, disappointment, unfairness, trauma: these central features of my mother’s planetary footprint also occupy much of her crowd-sourced ode. The anti-funeral, based on that text, was magical in that it embodied the knowledge that grieving has to be about the departed as she really was, reflecting her relationships as they really were. My ceremony celebrated and condemned her—both—and it did her the comradely service, at least, of letting her mourners breathe. Perhaps, as a result, thanks to my many-gendered with-women and my grief circle, my heart has broken sufficiently to allow posthumously for my falling in love with Mum again, the way I did when I was a baby. As Judy says, the dead inflict fresh wounds less easily than do the living, and so, they are much easier to learn forgiveness from.

For a discussion on amniotechnics, see Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now (Verso, 2019), excerpted in TANK Magazine →.

Madeline Lane-McKinley (@la_louve_rouge_), Twitter, August 16, 2002.

Laura Fox, “‘I have no idea what I’ve done wrong.’ Why I Distrust Parents of Estranged Children,” Mamamia, August 8, 2020 →.

Sophie Lewis, “Grief Circling,” Dissent, Summer 2020 →.

Roxanne Baker and Saralee Gallien, “Death Work,” interview by Maggie Foster, Mask Magazine.