In a much-cited essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey gave us a useful way of thinking about how we see: the male gaze.1 Her examples are all from classic Hollywood cinema, but the term has a wider application. For Mulvey, the spectator’s point of view is structured by heterosexual male desire. Cinema offers the particular pleasure of that desire in seeing without being seen.

The male gaze sees through the male protagonist on the screen, misrecognizing itself through his conquests of worlds and women. But this pleasure is undercut by an anxiety: the woman he desires is desirable because, in Freudian language, she lacks something. He has the phallus, and she does not. She might take it from him! That she is castrated is desirable. That she might be castrating is not desirable—at least for the male gaze of a straight cis man.

Plenty of screen theory also plays out what spectatorship is like for cis women, or for gay people. Mulvey even suggested elsewhere that there’s a kind of transsexuality to the female spectator within the male gaze when she misrecognizes herself in the male protagonist.2 I want to set that aside to ask about the trans woman spectator. Who does she become in the structure of the male gaze? To the trans woman spectator, the woman on screen that is both castrated and castrating might be the very thing to be desired.

I want to focus not so much on the male gaze, but on the cis gaze—a looking that harbors anxiety about the slippages and transformations between genders, but which also harbors desires for those transitions as well. I don’t want to think from the point of view of this dominating, controlling, and yet fragile cis perspective, nor even to critique it. I want to think, and feel, and imagine from outside of it. It’s no longer possible to think about the gender of the gaze without also thinking about race. I want to think beyond how ambivalent desires and anxieties structure the field of vision around race, sexuality, and gender, and decenter the sovereignty of the gaze itself.3

What is the cis gaze to that which is in so many ways its most negative object? In the context in which I work and play, this would be something like the black, queer, femme, trans body. What is it like to see, not from the point of view of film director Clint Eastwood, or the male protagonist of his Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), but from the point of view of one of the people caught in the camera’s gaze—the trans woman The Lady Chablis?4

Production still from the Clint Eastwood movie Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997). The still features Lady Chablis and actor John Cusak.

Of course, there are many black, queer, femme, and trans artists and writers, and even filmmakers, although the archive of their work can be fragile and partial. The archive itself constructs a gaze that refuses to see them as they might want to be seen, so the aesthetic I want to create here might need a little art and artfulness. What I love about Shola von Reinhold’s novel Lote is that, besides being a ripping read, there are, raveled into its elegant form, some concepts for just such a femme, trans, queer, and black aesthetic.5

To put it in these terms is reductive, because what’s great about Lote is that it finds other forms, other languages of the quaintrelle, the femme dandy. A quaintrelle aesthetic often appears as the bad object for the cis gaze, dismissed in that derisive and dismissive tone that Lote calls “International Cishet.”6 Whereas, from the point of view of its bad object, the unilateral pronouncements of International Cishet appear as less than universal: “The tectonic mascness of it all; that would have you think it’s neutral.”7

Lote centers on two black, quaintrelle characters. We don’t know the government name or assigned gender of Mathilda, who is addressed as “she,” while her friend Erskine-Lily is “he but not He.”8 That is, until that becomes unbearable too. “It’s being called the other thing. Man. So harsh, so vulgar. So … absolute. It always makes me feel sick. Quite disgusting.”9 That refusal, both conceptual and visceral, is a key moment in trans femininity, regardless of where a body might land within these linguistic shifters through which bodies are obliged to be dressed and addressed.

This quaintrelle way of thinking and feeling makes sense to me as a transsexual woman. It’s not my sensibility, but it is convivial. I can recognize it, play with it, feel like part of me can be alive here. It expands the repertoire of what a trans femme aesthetic can be for me. Lote is outside my experience when it comes to Mathilde and Erskine-Lily’s blackness. I’m a mere student of the place where the femme, queer, trans sensibility overlaps with blackness, within what Paul Gilroy called the Black Atlantic.10

Any interesting trans femme aesthetic in the spaces traced by the Black Atlantic will be one imbued, directly or not, with blackness, and at the deepest levels. To the European or American dialects of International Cishet, black, trans, femme, queer bodies are extra, too much, dismissed for being too wrapped up in appearances—appearances that, among other things, supposedly mark them as dupes of the beauty industry and a normative white idea of femininity. It’s an aesthetic that does its best to perform beauty without ironic distance or critique.

This is the essence of all the bad takes by cis writers on the 1990 ballroom documentary Paris Is Burning, from Tim Dean to Judith Butler to bell hooks: that the black transsexual attempting to don the mantle of feminine beauty is doing it wrong.11 To which one of von Reinhold’s characters in Lote retorts:

Between the “assimilation” and the fantasy there was another space which was not about championing anything that speaks against you—though that can be a literally fatal trap—but instead about showing your ability to embody the fantasy regardless, in spite of, to spite, and in doing so extrapolate the elegance, the fantasy.12

The gesture here is the refusal to allow anyone else to own this kind of beauty, to steal it back, to

abstract it and show it as a universal material, to be added to the toolbox. “Look! Look: it does not belong to them. Maybe we should not want it because they have weaponized it, but it was not theirs in the first place. Black people consuming and creating beauty of a certain kind is still one of the most transgressive things that can happen in the west, where virtually all consumption is orchestrated through universal atrocity.”13

Lote celebrates characters who are “Black fantasists, worshippers of beauty,”14 who are, in a lovely loaded phrase, “luxury stained.”15 Some are Arcadians, looking back for moments of idyll and glory. Some are Utopians, impelled towards Afro-futures. Some are Luxurites, consecrating their lives to the sensory now.16 Whether in the past, present, or future, there are dangers in all these paths, but also possibilities. Lote’s black queer, trans, and femme characters endure the world with aesthetic as well as political resources. “She pined, as she often did. Fantasized about the future. The Glittering Proletariat, skin perhaps as dark as her mother’s would have been.”17

Tourmaline, Morning Cloak, 2020. Dye sublimation print, 30 × 30 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist and Chapter NY, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Aesthetic survival tactics for the glittering proletariat under racial capitalism: manners and dress can work as camouflage, or its opposite. “Her costumes had the ability to temporarily dazzle onlookers into confusion, or sometimes admiration and awe,” but “without class, eccentricity loses prestige.”18 Best to look like a rich eccentric. Fortunately, the trappings of class can be acquired—without a fortune. Then one can receive the generosity of rich people without embarrassing them into thinking themselves charitable. “Rich people will happily prop up their own kind for years.”19

This facility with appearances is connected to the practice of the Escape, an especially useful talent in this treacherous age of trans “visibility.”20 Several characters in Lote are adept at it. “We did not want to become people hollowed out by generations of too much bad labor.”21 Appearing in a world, being embraced by it, then disappearing into another, leaving behind an empty simulacrum to hold the debts. “Never work!” as the Situationists used to say. An art for disreputable characters, disreputable to International Cishet and its twin, Global Whiteness, under whose gaze Escape is an art for those “born in a body that’s apparently historically impermissible.”22

Could there be a black quaintrelle aesthetic that exceeds the survival tactic of Escape? Mathilde is an Arcadian by temperament, who on rare occasions experiences a Transfixion, a sensation that comes over her in the presence of certain images of a particular kind of past life, those of the Bright Young Things who danced and glammed in and out of London between the wars. Each Transfixion resonates in its own peculiar way, perhaps as a “humming beneath the high fine rush.”23 The Transfixion is a sensation that vibrates around the gaze.

Transfixions trip a “feeling of not only recognizing, but of having been recognized.”24 It starts with a sense of mutual recognition, of the gaze being returned, but that’s not all. It engages the other senses, putting the gaze back in its place within a sensory communism. One of Mathilda’s Transfixions “induced the decorative wave in all things.” And another: “An excruciation of coil and kink … It made me ache with jealously and bliss.”25 Transfixions are those rare moments beyond the recognition of a body, a life, not unlike one’s own. They thrum and throb beyond and behind the gaze: an unseen sensation.

A Transfixion is not a recognition in an image of one’s identity. It is, rather, a dissolution of both the seen image and seeing self—black, femme, queer, trans, whatever. Both self and seen pulse in a cosmic subwoofer. What resonates is a rippling difference between the one and the other and the no-longer-actually-either—the style of a whole world. Since this is an aesthetic, the historical facts and biographical details need not matter, and in any case would reduce the Transfixion to a banality that its whole purpose had been to escape.

Potential objects of a Transfixion are likely to be on that margin that remains visible and proximate to a dominant culture. They have to stand in for possibilities even more marginal, those who escape the archive entirely. Mathilda’s key Transfixions are rich or rich-passing bohemians:

Freaks, marginal and queer, they may have been, but many of my Transfixions were of the same class and race, especially to begin with. God knows how some of them would have reacted had they met me … Conversely, history has buried many other potential Transfixions. I would still pass a building, and a particular curve in the stone would send me reeling with sensations and it could only be because the anonymous mason was a Transfixion, their life otherwise entirely unrecorded.26

This extrapolation from absent presence of a past is not unlike Saidiya Hartmann’s “critical fabulation,” but more fabulous.27

Transfixions recover the trace of the aesthetic aspects of artful lives from the margins of the archive that fall short of the existing category of fine art. Forms of art still reduced to merely ethnographic interest. “Framed art made by people that looked like me, throughout history, as something below art.”28 What is black, what is femme, what is queer, what is trans, can be decorative, but is only embraced as art under limiting circumstances, and often at the expense of abandoning or treating certain ornamental impulses ironically or critically.

While discreet about sex work, that most unacknowledged fine art, the ballroom aesthetes of Paris Is Burning made few other concessions. “Their love of Beauty, in that High Camp sense of the word, had not diluted their Blackness. It arose, monadically, from the same place.”29 There are different concepts of beauty here, even different ontologies, different ways in which beauty might (or might not) have being. Put simply, there is a difference here between ornament and form: between beauty as elaboration, modification, addition, the sensuous, the flesh; and beauty as essence, purity, whole(some)ness, and spirit. Beauty as adding, accentuating matter with matter; beauty as subtracting matter to reveal spirit. A difference coded, among other things, by race. Here’s how von Reinhold imagines the aesthetic universe of one famous white mid-century British modernist:

Wyndham Lewis, writing about his encounter with a “mulatto girl” at a party … describes her appearance as “driven by the barbaric and primitive will to ornament,” concluding that “the African blood is very much present in that one.” Perhaps Lewis had been reading Hegel who posited adornment as an undesirable primitive urge—and a feminine property of the Other. Hegel, like so many other thinkers from Plato to Adolf Loos, sought to preserve the image of an unholy triumvirate of femininity, adornment and Otherness.30

Loos’s most famous essay is called “Ornament and Crime.”31 It’s a foundational text of modernist design. Loos associated the ornamental with disease, paganism, the Negro, the criminal, the feminine, and with the “stragglers” holding back cultural evolution. Loos: “Freedom from ornament is a sign of spiritual strength.” Still, Loos might have been right about one thing: that Western culture had lost its own organic forms of ornament. As one black quaintrelle says to another:

The volute, you see, is divine, the sinuous line, the serpentine line, the corolla, the curl, the twist, the whorl, the spiral and so on, are all related in their volution, convolution, revolution. Volution is the essential and irreducible aspect of ornamentation, just as the phoneme is the smallest irreducible unit of sound in language. Locked into each coil, each curl of ornament, just like the coil and curl of your hair, and my hair, darling—Afro hair, as we call it—is the secret salvation of us all.32

Ornament, as Asger Jorn once put it, is a “pact with the universe.”33 Black Athena: that was the title of Martin Bernal’s controversial book that argued that the Greeks acknowledged Egypt as the source of their own culture.34 I’m not a classicist, so I don’t know if its argument works as cultural history. But perhaps it works instead as an aesthetic—one that frees us from that penetrating gaze, always piercing the veil of appearances with its dialectical arcing and leaping that supposedly takes us from the Greeks to white European modernism. That aesthetic that prides itself on shedding its fascination with ornamental trinkets to become the contemplation of pure form, in the process retrieving and uplifting the order and proportion of a classical Greek patrimony it claims as its possession.

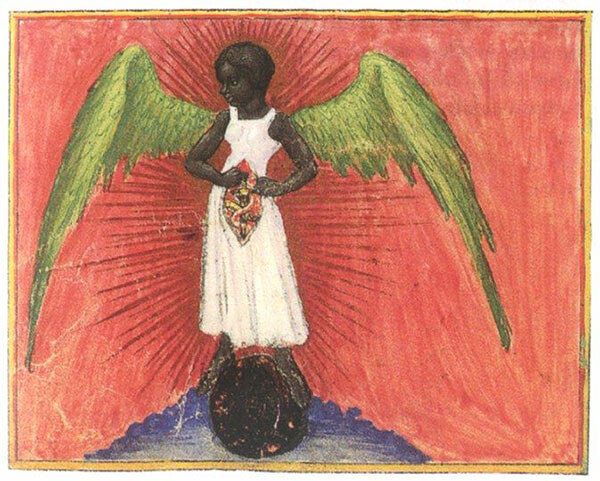

Illustration from the book Aurora Consurgens, 1420. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Folded away in this myth of Western inheritance, and from the beginning, is this:

Even the Greeks must at one point have realized the importance of ornament. They called the universe “kosmos,” meaning decoration, surface, ornament: something cosmetic. Like make-up. Like lipstick. Like rouge. The cosmos is fundamentally blusher.35

Cosmos indeed has this ambiguity, meaning both arrangement and adornment. To see cosmos as arrangement, as order, and not as ornament, as proliferation, is an aesthetic choice—one that is, among other things, racially coded. Maybe there’s a Transfixion that can happen when one is reading, when one feels a humming beneath the high fine rush in the glints and twists at the edges of certain texts.

Plato was quite the basher of ornamentalists. He had it in for what he called philotheamones—sight lovers, spectacle lovers. Framed them as veritable trash next to his kingly philosophers who loved the true beauty of ideas, not the decorative beauty of the world. Long after the Greek’s seriously puerile demotion of the ornamental, the Romans, Kant, Wincklemann, Hegel and all the rest damned it for being cosmetic. “Inessential ornament,” they called it. Quite hilarious really: if you ever need evidence of someone’s brutishness, it’s deeming ornament inessential.36

The Philotheamones had practices of the beautiful, of art, as a means of learning and being, that work through the sensual rather than discount it.37 This could be a conceptual practice, even if philosophy founds itself by refusing it. Kissing-cousins of the Philotheamones, aesthetically speaking at least, might be the Lotophagi, the lotus eaters, best known from the Odyssey (Book 9) and from Herodotus (Book 4). They too are sensualists, not of the eye but the mouth. Consuming the lotus makes them forget home and family. They are peaceful dreamers, and queer as fuck.

The Arcadian dream of Lote is for a Lotophagi revival. If you do a search for lotus eaters, you find many pages obsessed with trying to identify which island they came from and what plant they consumed. Who knows? Maybe their drug of choice was the blue water lily of the Nile, a common decorative motif in Egyptian art. Perhaps the lotus eaters are also an African invention—or could be. Or could only be.

What we have here, escaping around the corners of the cis gaze, is another practice of communication, and a different theory of it. The practice of aesthetic devotion in Lote is a gloriously eccentric one, centered on the visitation by the Luxuries. Like angels, the Luxuries work as intermediaries, performing what I’ve elsewhere called “xenocommunication.”38 They’re a limit case to communication, conveying sensation, through an absence, or impossibility, from the incommunicable. “Where we consider angels to be spiritual messengers, we might well think of the Luxuries as sensory ones, communicating with the aesthetic aspects of the soul. They are described as having skin like black marble.”39 They might be the agents of Transfixions.

Through the ritual staging of fabulousness, surrounded by beauty and after ingesting mind-altering substances, Mathilde and Erskine-Lily manage to conjure a visitation from the Luxuries. Nothing mystical need be imagined. Maybe it’s a fugitive dreaming, an auto-suggestive trick, a religious ritual. Or philosophical practice, to touch a “beautifully manic Geist.”40 Or an art. Maybe an aesthetic need not be about disinterested contemplation. Perhaps it could be an intensely interested and bodily sensation of the elaboration of the world. The beautiful is not the purposive with no purpose. It has a purpose:

The sensation of the beautiful arises because something is beautiful and that this sensation has a functional property. If there was no beauty the sensation would not arise and one could not commune with the Luxuries—one must appreciate the beauty in and of itself to be able to experience the sensation which allows one to confer with those Beings, which is indicative of their presence.41

“Commune” is a delicious word here. A participation in a beauty that is not a property of any particular thing or anyone’s possession. Lote can be read as a fantastical instruction manual for the “aesthete communist.”42 Or as I call it: femmunism.

If the slave-owning Greeks mastered geometry, perhaps it’s because they were also land owners. Geometry is, among other things, a technique for marking and measuring out estates. Perhaps it’s no accident that the more Apollonian strain of Western modernism took its cue from the blanched, looted ruins of Greek marble, and took their temples as a template for the spirit of good form. Property, order, purity, form; and against that, the surround: all that it excluded, such as what is black, femme, queer, and trans, if one must point with such words.43 And in and against good form and good order, an aesthetic communism, the volunteers of the volute: “Unwitting antibodies of the Totality.”44

Lote helps me think through a couple of things. One is a tempering of my instinct that a trans femme aesthetics always has to be an avant-garde one.45 I still think forms designed to marginalize us need handling with care. What Lote teaches me is that: “Until the Black diaspora, amongst various other groups, have come close to that length of commodious interaction with the form … then perhaps these pronouncements should be rephrased from ‘painting is dead,’ to ‘white people shouldn’t paint.’”46 Or write, perhaps.

Aaliyah King in Walk For Me (2016), a film by Elegance Bratton.

The other thing I am learning from Lote is the whole category of the beautiful. In writing for e-flux journal about Jessie Rovinelli’s 2019 film So Pretty, I juxtaposed an aesthetic of the pretty to the beautiful.47 There, the pretty as a low technique, outside the exalted realm of beauty as good form, seemed to be a way to think of a trans femme aesthetic. But there’s a certain luxury in white girls like us, Jessie and myself, dispensing with beauty in favor of the pretty as something more everyday—and, in my case, more vulgar. Von Reinhold starts, rather, with the matter of blackness, to claim the beautiful as what is most high—partly for survival reasons, and partly also as a different line of aesthetic claim to space, to glory.

Not that I ever thought there would be just one trans femme aesthetic, as if there were some essence or style or unity. It is rather a disparate set of tactics for being in the world—as a being, and as a world—that can construct a situation that is pleasing, for as long as it lasts. And in ways that can cast a refrain that can echo, that can be felt and heard, that our cultures might learn and elaborate and grow from—and to endure. And that can construct a situation from which the Transfixions to come would be more than shadows.

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Visual and Other Pleasures (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Laura Mulvey, “Afterthoughts on Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema Inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun,” in Visual and Other Pleasures.

On the sensory and embodied side of a trans aesthetic, see Cáel Keegan, Lana and Lily Wachowski (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

The Lady Chablis, Hiding My Candy (Pocket Books, 1996).

Shola Von Reinhold, Lote (Jacaranda Books, 2020).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 388.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 389.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 438.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 390.

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic (Harvard University Press, 1994).

bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (South End Press, 1982); Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (Routledge, 1993); Tim Dean, Beyond Sexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 209.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 209.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 365.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 367.

On Afrofuturism: Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant Than the Sun (Quartet Books, 1999); on black luxury: Madison Moore, Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric (Yale University Press, 2018).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 371.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 278–79.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 59.

On the ambivalence of visibility, see Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, ed. Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton (MIT Press, 2017).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 58.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 24.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 30.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 31.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 28.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 208.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (June 2008).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 208.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 210.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 275–76. On Wyndham Lewis’s fascist modernism, see Fredric Jameson, Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist (Verso, 2008).

Adolf Loos, “Ornament and Crime” (1908), in Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture, ed. Ulrich Conrads (MIT Press, 1975).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 312.

Quoted in Graham Birtwhistle, Living Art: Asger Jorn’s Comprehensive Theory of Art (Reflex, 1986), 35.

Martin Bernal, Black Athena Writes Back: Martin Bernal Responds to His Critics (Duke University Press, 2001).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 312.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 312–13.

Constance Meinwald, “Who Are the Philotheamones and What Are They Thinking?,” Ancient Philosophy 37, no. 1 (Spring 2017).

Alexander Galloway, Eugene Thacker, and McKenzie Wark, Excommunication: Three Inquiries in Media and Meditation (Chicago University Press, 2013).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 311.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 409.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 409.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 403.

I lifted “surround” from Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Autonomedia, 2013).

Von Reinhold, Lote, 62.

McKenzie Wark, “Girls Like Us,” The White Review, December 2020 →.

Von Reinhold, Lote, 183.

McKenzie Wark, “Femme as in Fuck You,” e-flux journal, no. 102 (September 2019) →.