Nikos Papastergiadis: Where does the concept of lumbung come from?

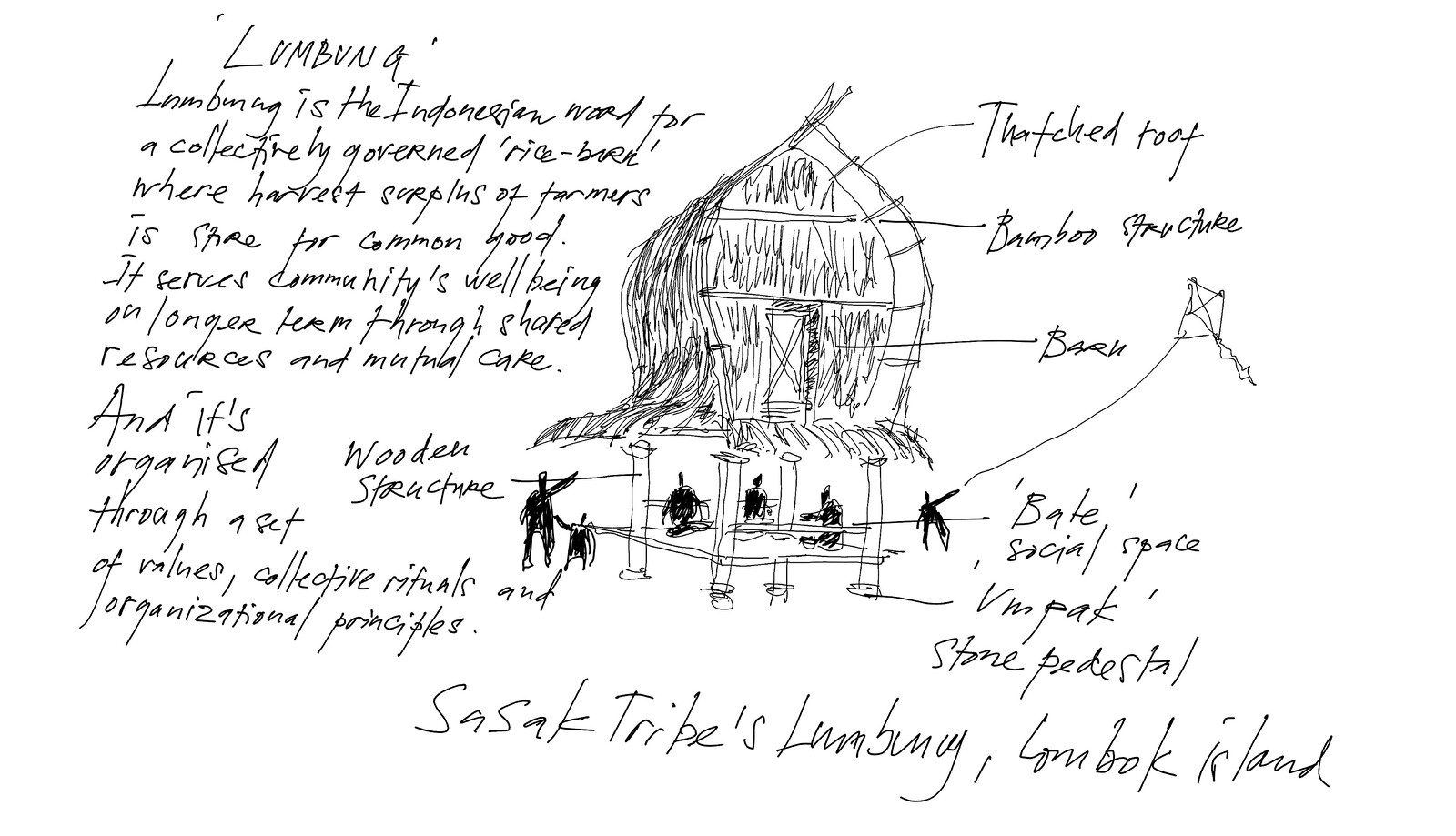

ruangrupa: Lumbung is a traditional agrarian practice in Indonesia. It refers to the process of sharing resources. The word “lumbung” literally means “rice barn,” a structure commonly used by villagers to deposit and store their surplus crops. It also functions as a space to meet, celebrate, and share appreciation for the previous harvest. As architecture, it can only remain relevant and sustainable if its users continuously renew and refill its resources.

NP: How have you adapted this practice for the context of contemporary art and society?

r: Agrarian traditions across Indonesia operate on the principles of sharing. When it is time to harvest, the surplus is not exhausted, but collected and stored in the lumbung instead. The excess crops become something to be used by the community in times of scarcity, like a climate-related disaster or famine. By carefully maintaining the resources available within, farmers also give themselves time to rest and allow the soil to recover. We see lumbung as a principle for collaboration. We are concerned with how resources—both tangible and intangible—can be shared. Exchange and distribution of knowledge have always been at the core of our practice. We adapted this agrarian concept to an urban environment. More specifically, we saw the living room of a domestic home as a lumbung—a space where various skills and networks that come, circulate, and shift are hosted. It is built on the initiative of people who have the same needs, who try to organize themselves to share resources and have space to grow together along with the surrounding community. In the context of contemporary art and society, lumbung is an idea for not only mapping resources but also identifying and understanding basic needs and self-limitations, to define the resources and surpluses of each initiative/organization to be shared with others. It has informed our ideas around sustainable, self-initiated interdisciplinary spaces. It is where art meets social activism, management, and various local networks. It was central to forming our collective, ruangrupa, and to understanding what is happening in our local environment and responding to it by initiating something together within that context. Lumbung is not a theme, but a concept that we’ve practiced and a principle we have operated on throughout the journey to documenta fifteen and beyond.

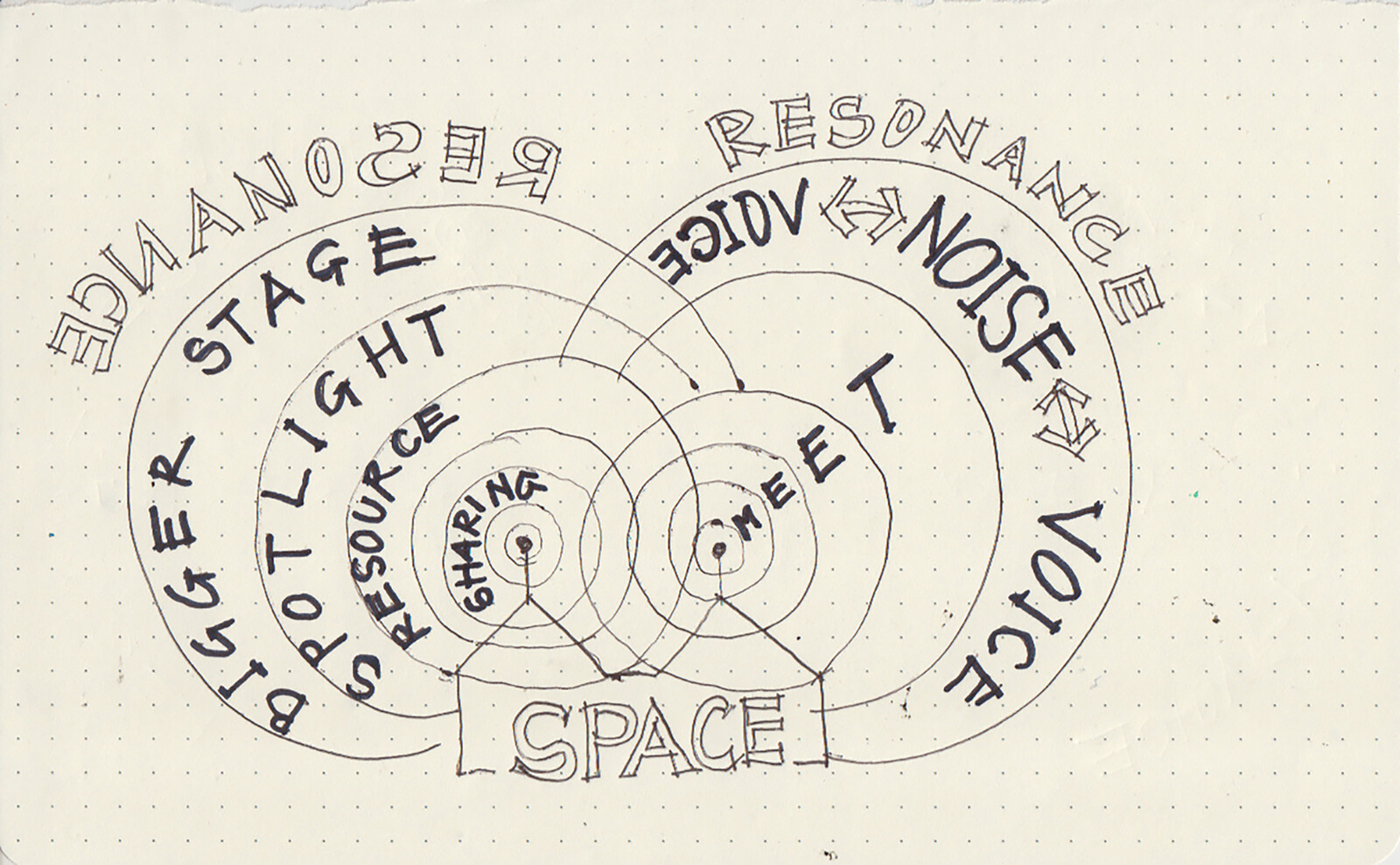

NP: Apart from sharing and sustainability, what other principles does lumbung highlight?

r: Sharing and sustainability enhance well-being. We see the systems supporting art as a means to focus on the well-being of the entire ecosystem. However, this also takes us to the principle of respecting different concepts of time. The modern emphasis on efficiency has ignored the richness of time in diverse cultures. Uncertainties and failures can be seen as luxuries—luxuries that contemporary society compels us to do without. Money is not everything. Time is.

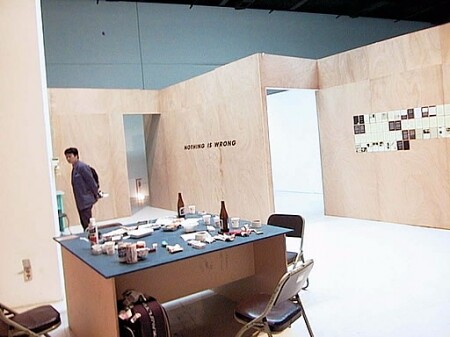

Courtesy of Iswanto Hartono/ruangrupa.

Courtesy of Ade Darmawan/ruangrupa.

Courtesy of Iswanto Hartono/ruangrupa.

Courtesy of Ade Darmawan/ruangrupa.

Courtesy of Iswanto Hartono/ruangrupa.

Courtesy of Iswanto Hartono/ruangrupa.

NP: Do you also draw on older concepts of power, listening, gathering, and leadership?

r: We need to consider power as something that’s not absolute. Power is not embodied in a structure; it is in rotation and interchangeable. What’s needed for our continued collaboration is an ability to play different roles with good endurance. This kind of sensibility towards rotation is important. To move between leadership and followship is powerful. Strong articulation and silence are equally respected.

The term “majelis” refers to a space where people sit side by side, sharing, discussing, speculating, solving problems, sharing food and humor without time limits. In Jakartan slang, the word “nongkrong” is used to describe this activity. It can even mean doing nothing collectively. Within aimless conversations between friends is a sense of mutually taking care of each other.

Another phrase is “musyawarah-mufakat,” an assembly that humbly gathers to make decisions for the sake of the common interest. The group doesn’t cast votes and go with the majority, but reaches consensus by talking things over. A musyawarah-mufakat can be held without a set time frame and is very open in nature. Another phrase, “gotong royong,” refers to a form of mutual cooperation among a number of people to carry out a task deemed useful for the common good. This phrase emphasizes the active participation of individuals in the community.

In sum, we are drawing on ideas that bring people together in conversation rather than force them into authoritative processes. Conversations meander, and decisions spring forth. We reduce individual control and ownership. We share power and authority, as well as respecting silence and absence. Ideas emerge organically without clear intellectual ownership. It is a collage: thousands of pieces of ideas come together. Bad ideas are polished up with a little collective imagination.

NP: When did ruangrupa start, and what were the conditions that spawned its existence?

r: ruangrupa started with a friendship between art school students in Jakarta and Yogyakarta in the 1990s. It formally came into existence in 2000, which coincided with the end of the Suharto regime (1966–1998) and the loosening of restrictions against freedom of expression and public assembly put in place by the “New Order.”

NP: What were the goals of the collective?

r: The primary goal was to create space for discussion and experimentation with art. Before this period, it was considered a subversive act to form an organization or hold self-organized events without permission from the authorities. There was very rarely space dedicated to diverse art practices, especially for young artists. The literal meaning of the word “ruangrupa” is “visual space.” In the beginning we usually met in our living rooms or houses.

NP: What other spaces did you seek to occupy, or rather hang out in?

r: Sometimes we organized our programs in other emerging art venues. After a while we did fundraising to rent our own space, where we began to organize workshops, exhibitions, discussions, and publishing activities. During our time in art school in the mid-nineties, some of us collaborated on various projects: zines, music, criticism of authority and establishment positions. After the economic crisis of 1997, the student movement came to a climax in 1998 and led to the reformation. We were conscious of the reality that public space can never be taken for granted. It can be taken away, sold off, and controlled. ruangrupa thinks of public space as where people can identify themselves as social beings. This is vital for any society. The establishment of public space was one of the main reasons for forming ruangrupa.

NP: Where does artistic practice end and public engagement begin?

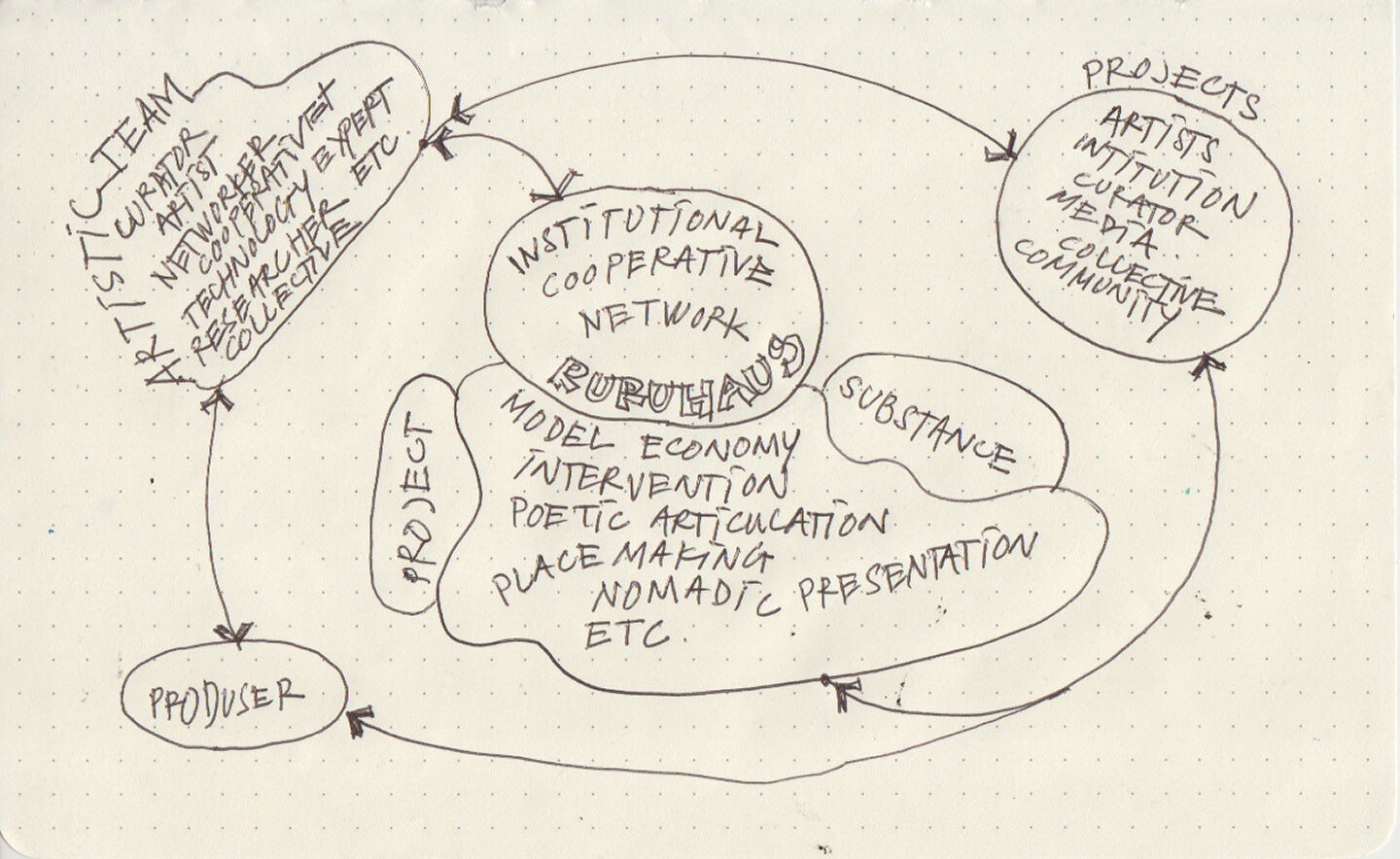

r: Slowly and informally, ruangrupa has become a school with many people. However, we wanted to go beyond traditional art education that’s focused on developing individual talent and spotting budding geniuses. Believing that art and artists can no longer exist for their own sake, practicing collectivity, and working collaboratively are all methods to take a stand in society. We established Gudskul in 2018 with two other collectives, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara, to encourage an initiative spirit in artistic and cultural practices. By using this approach, artists simultaneously and organically act as producers, mediators, distributors, and networkers. We designed Gudskul as a space for process-based study, collective-practice simulations, and critical and experiment-based learning and sharing. Gudskul is meant to promote collaboration and self-organization. It’s a collective learning space as well as a contemporary art ecosystem built on friendship, equality, and solidarity.

NP: When you started out, were there similar groups and collectives in Indonesia that shared these goals?

r: There were numerous initiatives across many cities in Indonesia. At least two common tendencies could be observed among these organizations and groups. First, their artistic practices, whether collaborative or individual, constituted their artistic statement as a group. Second, they acted as support systems within the larger art ecosystem through activities or programs that raised public awareness. The activities were wide ranging, including exhibitions, workshops, festivals, discussions, publications, film and video screenings, website development, archiving, and research. Almost all of these collectives started in the participants’ and organizers’ homes. They all shared a desire to meet in comfortable spaces, hold discussions, and then let things happen.

ruangrupa, Lekker Eten Zonder Betalen, Cemeti Gallery, Yogyakarta, 2003. Photo: ruangrupa.

ruangrupa at the Gwangju Biennale 2002, South Korea. Photo: ruangrupa.

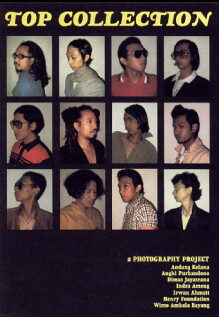

ruangrupa, Top Collection (poster), 2004. Courtesy of ruangrupa.

Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem (GSE) is a collective of collectives, initiated by Serrum, Grafis Huru Hara, and ruangrupa, among others. Between 2016–18, these Jakarta-based collectives started experimenting with the notion of lumbung in the buildings pictured above. These experiments were the seed of what has become Gudskul today, an informal education program and public learning space. Courtesy of Gudskul.

Instagram announcement for a Blackbox Karbon radio event organized and hosted by ruangrupa’s Ruru shop. Photo: Ruru Shop.

Chairul Insani, Sand-Sack Tinju, 2006. Site-specific installation. This installation was shown as part of Jakarta 32°C, a biennial organized by ruangrupa that presented work by art students living and working in Jakarta. Courtesy of ruangrupa.

ruangrupa, Lekker Eten Zonder Betalen, Cemeti Gallery, Yogyakarta, 2003. Photo: ruangrupa.

NP: These spaces mixed the private and the public, the domestic and the civic, politics, art, and life. How did the groups survive financially? What sort of mix of private patronage, state funding, and commercial opportunities enabled the group to keep going?

r: Most artists tended to come from the same social and economic class as their neighbors. Most artists divided their time working in the creative and media industries as freelancers, or were students. The collectives were also often located in working-class or mixed-use neighborhoods and coexisted with small and medium-sized independent businesses.

Most of us are also active with individual projects in diverse fields: visual arts, design, music, architecture, teaching, writing, research, or a mixture of everything :). This intersection and interdependency between individual and collective senses enriches ruangrupa in practice. From the beginning, ruangrupa has survived as a lumbung of collective resources, time, energy, ideas, and also money; the mixture of our individual and collective activities is what makes our lumbung richer and sustainable.

By acting as a stand-alone citizens’ initiative, the group rendered its vitality by becoming a form of supportive infrastructure for both art and the community. It envisioned itself as living among the people. Our neighbors’ unmediated influence and involvement could also act as an artistic exploration strategy.

The lack of governmental funding and infrastructure does mean that all such initiatives in Indonesia are vulnerable. Spaces and programs can be easily lost, and people are overworked and underpaid. Sustainability and independence are two words that most often only cast a shadow. Independence is almost impossible to achieve when survival depends on foreign donor agencies and private sponsors, which often focus only on the production process and not on the processes of sustainability.

Our biggest challenge is how to create a platform that can carry on and translate this mode of artistic practice throughout increasingly rapid societal changes. Through our expanded notion of artistic practices, we are attempting to build a new model which takes into account the economy, culture, politics, labor ethics, and collaborative habits. Only through such a model can the separation between art and life be truly overcome. During the Suharto regime there was a vertical fight: the people versus the state/authority. This transformed into a horizontal contest: the people versus the people. It is also interesting that in the post-reformation period there is an ongoing horizontal spatial contest.

NP: Did the absence of formal arts infrastructure act as a burden, in the sense that it needed to be built, or was this an opportunity to reinvent it?

r: The fact that it was nonexistent meant that all of the thinking towards better or even ideal living ecosystems has always been generated from the bottom up. Of course, there was always the democratic hope that the state would at some point embrace these ideas.

Our role is therefore to be problem solvers, and creating living spaces was a sort of “contextual response” to the problem of infrastructural lack. These types of spaces do not rely on the state at all, and most of them are not even connected to their local arts committees. Unfortunately, there aren’t many opportunities for independent arts organizations to partner with state institutions. What these circumstances really reflect is the failure of the state’s central planning to facilitate the vast growth of ideas in different localities.

NP: What happened to ruangrupa when it started to expand by linking up with other local initiatives, and also gain international opportunities?

r: In 2015, when ruangrupa had the chance to rent a bigger space in Jakarta, we decided to evolve. The focus was not merely on our collective; instead, we transformed into a collective of collectives. Together with Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara, who run a new space together, we’ve become an ecosystem by putting various resources into a lumbung to support and strengthen each other.

During the same period, we started developing RURU Corps, an experimental business. We were looking for ways to generate more income in order to be more financially independent in the future—in short, to survive with what we already have. At the same time, we aimed to run a space at a scale that allowed us to practice a form of institutional activism. It trained us to tend to this “self-initiated institution” while opportunistically using it as a meaningful place of knowledge production. This led to working together with programmers and curators to experiment with how to sustain their programs, as well as the creation of various forms of local creative markets and commercial creative services such as website design, video making, event programming, and festival organizing.

NP: How does ruangrupa operate in the public domain of a foreign city? What are the challenges as well as opportunities afforded by directing documenta fifteen?

r: When we were invited to offer a proposal for documenta fifteen, we decided to respond with a counter-invitation: for documenta to become part of our ecosystem, through a collaboration inspired by and modeled after lumbung. Since lumbung is a form of organization for a common governance of resources, the question then becomes: How can we govern these resources together? One answer is to keep extending the invitation to others. The lumbung—an ecosystem benefiting, contributing to, and caring for this extensive ecosystem—will be collectively built over the span of three years and beyond by different collectives and institutions from around the world. On our radar are groups from remote and rural areas in Spain, and Central and Eastern Europe. We imagine members from places such as Southern Africa and Mali that have deep experience in Ubuntu or Maaya traditions of sharing. We are also thinking of places like Colombia, Hungary, and Palestine that are challenged by populism, neoliberalization, and conflict, but also have rich histories of resistance and creative practice.

The challenge for the artistic team of documenta and the different groups is to develop a common pot. Each group will bring distinctive resources, and new surpluses will emerge. However, it will also require building trust and lasting relationships. This will require visiting each other and exchanging knowledge. In order to find mechanisms for distributing resources, the groups and institutions will meet regularly, forming majelises (assemblies). In turn this will lead to inviting others to join as well. This will become “Lumbung Inter-lokal”: an incubator for a wider transformation that questions the current global art economy.

The new arts economy that we are aiming to build brings art back to its more useful function: the imagination and realization of new (and remembered) ways of living and organizing that are more just, humane, and holistic. We are therefore looking for friends that focus their artistic experimentation, activism, and/or imagination on the fields of (urban, rural, public) space, economics, education, and ecology. We’re interested in organizations that cherish relations, generosity, and the search for the rebalancing of individual and collective needs. In the first phase of crafting this new art economy, collectives and organizations that already have this at the core of their mission are invited to enrich the lumbung economy with their own experiences, activities, and resources.

NP: How has the Covid pandemic disrupted your plans to turn Kassel into a living room for documenta fifteen, and what are the ways in which you can plan for people to hang out and share in the future?

r: We have used the lumbung model to take care of each other during this crisis. In the beginning of the pandemic our space could not be used in its normal way. It became our surplus. We had to use it differently in order to contribute to the situation. So we transformed the auditorium into a small production place for hazmat suits and masks. We did fundraising to support local medics and hospitals in the remote islands of Indonesia. Our friends worked from home or in shifts to minimize exposure.

Obviously, we had to cancel many events or rethink how to host things on digital platforms. When we realized that things were not coming back to normal anytime soon, we started to feel drained and frustrated, and decided that we needed to split ourselves into small groups in order to be more flexible. We thus started to see the whole organization as a collection of smaller connected units. Now we coexist in a physical and virtual way; even our majelises and markets are done virtually. We still hang out in shifts: a few friends are working at Gudskul, and spontaneous Zoom links are open for anyone who would like to join, with no fixed schedule, topic, goal, or time limit. It is still an open space where people can come and go. It does not replace the usual way of being together, but it does keep the conversations going, keeps us sane and caring. I think this pandemic has taught us not to underestimate the power of hanging out.

Category

Subject

This conversation was initially commissioned by Charlotte Day (Monash University Museum of Art).