We were amazed by what we saw, because everything had changed and was buried deep in ash like snow.

—Pliny the Younger on the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 791

A people

becomes poor and servile

when their language is stolen from them

inherited from their forefathers:

it is lost forever.—Ignazio Buttitta, “Lingua e dialettu,” 1970 (translated from Sicilian)

On and around the base of Mount Etna, in the summer it’s fairly common for small lava fragments to snow down from the sky. Etna, on the east coast of Sicily, is the largest active volcano in Europe. As the lapilli fall, they cover the sea and the cacti along the coast, local Ancient Greek and Roman theaters, as well as the streets and baroque palaces of nearby Catania. The latter were built in lava stone after a 1669 eruption of the same volcano destroyed much of the city. Lapilli land on hypermarket parking lots, lemon orchards, and vineyards that produce the mineral-rich Etna Rosso. One finds fragments under their fingernails, between flip-flop thongs, in bedsheets, underwear, in the fruit bowl. This connection of the volcano to body and landscape has mystified and frightened inhabitants of the island for millennia, as evidenced by accounts of Etna that blend beauty and danger, fertility and destruction. In the local versions of Greek mythology, Hephaestus forged his weapons for the gods on Etna’s snowy peaks; for Greeks on the mainland, it was the home of Typhon, one of their most terrifying monsters. In Sicilian tales of King Arthur dating back to 1066, his court is not gathered around Glastonbury Tor in Somerset, but on the volcano. King Arthur sleeps on Etna for eternity, sustained by the Holy Grail.2 When it falls, the black snow seems to stop time. Its cascading shadow of dust casts an outline of the surrounding human, nonhuman, and folkloric landscapes on Sicily.

Sicilian is the only language on the European continent without a future tense. While scholars continue to debate when exactly Sicilian developed, during the twelfth century a popular language made up of Latin, Greek, and Arabic dialects had already begun to coalesce, mixed with the particular Latin spoken by the Norman French who ruled the island at the time.3 Also, in the Sicilian dialect of modern Italian, as elsewhere in the south of Italy, it’s not uncommon to use the passato remoto (the distant past tense) for events that happened just that morning. In “standard” Italian, that tense is reserved for the really long ago. These alternate forms of expressing time in speech, and thus memory, do not mean that Sicily should be essentialized into a primitivized pastoralism. Nor should its futures be foreclosed, as mafia crime dramas, their literary influences, and elite, liberal neglect are wont to do, particularly in writing or rule from outside the island.4 Instead, it is a linguistic invitation to think outside of time as “we” know it. When the French historian Fernand Braudel describes seeing workers across the Mediterranean, in introducing his vast thinking of the complex area, he fittingly writes that in “looking at them, we find ourselves outside of time.”5

All around the Sicilian island, sites, languages, and popular dispositions exist in interwoven moments across ancient and contemporary time. For example: the steps to the main square in Aci Trezza, memorialized in Luchino Visconti’s neorealist classic La Terra Trema (1948), face three large rocks that jut up from the Ionian Sea. According to Homer, the Cyclops threw these stones at Odysseus. Outside of myth, the stacks are older still: they emerged from underwater eruptions that predate Etna itself. This comingling of lore, geology, and human history concentrated on one island calls out linear, European time for the cruel joke of modernity that it is.

Pier Paolo Pasolini on the set of his film Pigsty (1969), on Mount Etna. Copyright: Salvatore Tomarchio.

This essay takes these linguistic specificities of Sicilian time as one of two foundations. The other is a film-historical recurrence: Pier Paolo Pasolini, a Friulian who frequented the subproletariat slums of Rome, chose to film four of his movies in the late 1960s and early ’70s on Etna.6 Per film critic Sebastiano Gesù, Pasolini selected Etna because of its dualisms: “the union of the opposites: death and fertility, sacred and profane, … heaven and hell.”7 I suspect that he chose the volcano because of its hundreds of craters and surrounding areas covered in lapilli, freezing what’s there under its wavy surface.8 In 1959, Pasolini had driven down the entire coast of Italy in a Fiat 1100 to write a column for Successo called “La lunga strada di sabia” (The Long Road of Sand, later published as a book). Scholar Ara H. Merjian writes that during his journey, Pasolini drew “reassurance, in any case, from phenomena that remain unchanged. Driving between the cities of Catania and Siracusa in Sicily, he travels for forty kilometers without seeing another car or kitchen light. He likewise finds the island of Ischia [near Naples] ‘as it was two thousand years ago.’”9

So much was written in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries about methods of capturing time: the photograph entombing Muybridge’s horse mid-gallop, atomic bombs imprinting everything in their radioactive waves as shadows of an instant, the assembly line and the making of the working day, the expropriation of labor power and its metabolization into exchange value. Unlike these violent processes central to colonial and capitalist modernity, and contrary to Sicily’s depiction in mafia tele-series or the mocking tones of journalists from the North, Etna’s lapilli snow and its language are gentler methods of capturing an instant or a series of instants. Perhaps they even constitute a way of communizing time.10

Jamie Mackay’s The Invention of Sicily: A Mediterranean History offers a recent corrective to much of the exoticization of Sicily in English-language studies and accounts. Covering over two and half millennia, Mackay follows the island’s “history as an autonomous community rather than just a parenthesis to that of its better-known imperial masters.”11 It is a locale, in this telling, that has during all these centuries produced autonomous subjectivities and sensibilities, even dissident ways of life.

By contrast, earlier this century, in a typical vein, critic George Scialabba clumsily described Sicily this way: “An unbroken history of rule by irresponsible elites—landowners, the Church, and the Bourbon monarchy—has left the island without civil society or the virtues it makes possible: no solidarity, no trust, no enterprise, no public spirit, not even simple honesty.”12 Scialabba ignores that solidarity, trust, enterprise, public spirit, and honesty—and not of the simple variety—are the very qualities that allow people to survive and contest domination in the first place. Mackay, in contradistinction, clarifies:

While historians often describe Sicily as being “multi-cultural,” they usually do so as shorthand to describe a string of colonisations by Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, French and Spanish, among other peoples. This is valid to a certain extent. There’s a danger, though, that such a narrative ends up presenting the Sicilians themselves as passive victims of these global powers. Of course, anyone who has spent any time on the island will know that this is absolutely not the case.13

While documenting those centuries bookmarked by tragedy, from the Spanish Inquisition to the collaboration between Mussolini, the Church, and the mafia to destroy working-class movements, Mackay also highlights Sicily’s histories of rebellion: peasant revolts, medieval cosmopolitanism that defied the Catholic crusades, preunification working-class attempts at collectivization, and ongoing resistance to fascism.

Through Pasolini’s eyes, also attentive to these riotous histories and presents, Etna and its surrounding linguistic realities become allegory and experimental setting rather than a site to insert into processes of ossification, as in the harsh forms of objectifying and valorizing time listed above. In this text, I follow Etna’s lead by way of the director, presenting a few shadows, outlines of images from film, literature, and territory that wonder whether Sicily’s attempts at autonomy throughout history stem from its landscape as much as from its language. At best, Pasolini’s images, spurred by the appearance and practice of autonomy, set on this mineral-rich soil painted a deep gray, become roadmaps to a different, noncapitalist way of life. At worst, they are a very sexy critique of the postwar fetish for consumption and development, still with us even if they are decaying and expanding into neofascist realities faster than the ash can cover them up.14

Timelessness in Theorem

This transformation in the art of government did not escape the attention of Pasolini, who diagnosed it within developments in spoken Italian following the war, in the moment of Italy’s total, ferocious industrialization and metropolitanization. Pasolini wrote: “I believe that there has been a substitution, as a linguistic model, of the language of infrastructure for the languages of the super-structure.”

—Marcello Tarì, 202115

In Pasolini’s Theorem (1968), a visitor gently invades a bourgeois home in Milan. During the film, he seduces—or is seduced by—each member of the family, producing tidal effects: the son discovers his (homo)sexuality and leaves to become an artist, the daughter acknowledges her ability to lust and be lusted after, the mother unshackles herself from domesticity, and the cleaner becomes a mystic, eventually returning to her village. Film critics and other thinkers have justly analyzed each of those relations and happenings for how Pasolini displays and disrupts the notions of libidinal desire in industrialized societies.16 My primary concern is the influence the stranger has on the father. The stranger’s care and attention win over the father while he lies in bed, deeply ill. After having been penetrated by the visitor, the industrial magnate rids himself of all his property, gives his factory to the workers, and proceeds to strip himself naked at the train station before heading into the wilderness.

The final scene sees the now-propertyless man screaming into the camera amongst the black hills of Etna. While he might appear to be in despair, or in some sort of panicked rage, his screams can also be interpreted as his escape from bourgeois morality and industrial modernity. He has ceded value to its abstractions. Pasolini moves the character, forever changed, from his Milanese estate to a pre- or postcapitalist land, devoid of people, money, or power.17 Where better to stage this transformation than on the barren, fertile volcano? Looking at the deep black of the soil, at the hundreds of dormant craters lining the slopes of the mountain, it could be mistaken for a wasteland. On closer inspection, there are dark black wild boars and bright ladybugs, geckos, pine forests navigating around the paths of former lava slides, cacti and succulents crawling up and down the slopes, and on the plateaus, grapes, olives, and honeybees are all fed by nutrients from the raining lapilli. On the horizon is the Mediterranean Sea, with a coast constructed by eruptions from between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates. That something ostensibly devoid of life is instead so fruitful is a fitting metaphor for a space outside of capitalist time. It is not “primitive,” it is ahistoric; a different world is not imagined from the ashes of the current capitalist one, but with disregard for it altogether.

Pasolini’s Pigsty (1969) uses the volcanic setting differently. In tells two parallel stories: one about the fascism implicit in industrial capitalism and the performativity of bourgeois student radicals, and the other about the hysterical nature of human law. In the latter storyline, shot on Etna, an unknown man in an unknown time and place wanders through black hills, devoid of anything other than desire. He turns into a cannibal, teams up with a thug, and is eventually executed by the powers that be, while uttering a now-famous line: “I killed my father, I ate human flesh, and I quiver with joy.” Unlike the patriarch in Theorem whose screams signal the abandonment of bourgeois civility, the maneater finds utter joy in open rebellion against even the most basic of human social norms, though in the process he becomes something of a monster himself. Backwardness becomes directionless.

Both these uses of the landscape differ from Visconti’s La Terra Trema, the proto-workerist parable shot just a few kilometers away on the sea. There, the camera closely follows the lives of fisherman in Aci Trezza, who are at the (lack of) mercy of wealthy capitalists from Catania who practically own their lot and their bodies. When one young man tries to go it on his own, he and his family are destroyed, evicted, made exiles. Pasolini’s Etna is the other side of this enclosure; we see the cannibal in wide shots that are more interested in the landscape than the character’s wandering. By contrast, Visconti’s neorealist tracking shots closely follow the protagonists to emphasize their misery. Pasolini’s tale is certainly not workerist, but it isn’t post-workerist either; rather, it’s outside of the totalizing logics of the wage altogether, meaning his critique is not confined to forms delineated by capital (the wage form, the union, etc.), even in contradiction.

Benvenuti al Sud (Welcome to the South)

In the North, the Communists knew everything about Communism. But it is a knowing everything that ended by a knowing nothing. There in the South they knew nothing, and it was as if they knew everything.

—Leonardo Sciascia, Candido

Pasolini first came to the island in May 1959 on a trip organized by the Italian Communist Party (PCI) to document the destitution of the South for Northern cultural elites.18 “Sent by Giancarlo Pajetta … in order to denounce the miserable living conditions of the residents of the Chiafura area who lived in rock caves, with no water, electricity or sanitation,” the expedition also included politician and art critic Antonello Trombadori, the painter Renato Guttuso, and the historian Paolo Alatri.19 This was all in the context of the postwar era when (already compromised) left parties had explicitly abandoned proletarian liberation and the collectivization of property in favor of economic productivity and the development of a brimming industrial, bourgeois economy. Soon after WWII, the PCI took a decidedly anti-revolutionary position, sharply denouncing “militants who spoke bluntly of establishing working-class power.”20 Indeed, the insistence of the PCI and PSI (Italian Socialist Party) on the expansion of the wage contract and labor productivity necessitated seeing not-yet-fully-enclosed or not-yet-fully-privatized forms of life, like those still found in parts of the South, as backward and in need of rapid development.21

On that first visit, Pasolini interpreted the destitution he saw in Sicily not as backwardness—though the island was certainly miserably poor—but rather as an image of resistance, or at least a refusal to play ball. He would return to the island that same year for his road trip. Perhaps Pasolini saw something similar to what Veronica Gago saw during the 2001 insurrections in Argentina, where she discerned forms of “destituent power” in the eruption of popular mobilization. As opposed to the constituent power of capitalist nation-states, destituent power, writes Gago, has the “capacity to overthrow and remove the hegemony of the political system based on parties … opening up a temporality of radical indetermination based on the power of bodies in the street.”22 In his 2020 book on Pasolini and the volcano, Gian Luigi Corinto seems to agree when he writes that the figure of Christ in The Gospel According to Saint Matthew, another of Pasolini’s films shot on the volcano, “is imagined as a revolutionary who contests constituent power.”23 Marcello Tarì introduces another way to think about the destitution of power—which can be mapped in Pasolini—through Benjamin’s notion of the “proletarian general strike” (in which the suspension of law coincides with the end of violent exploitation) as opposed to the “political general strike” (always characterized by constituent violence). As he writes:

A strike becomes truly destituent when it no longer allows for the reconstruction of the enemy’s power … The Destituent strike demands nothing; it makes a negative claim. Perhaps Pasolini was not thinking of something very different in his famous and much discussed poem Il PCI ai giovani [the Italian Communist Youth Federation], provocatively addressed to the students of ’68, but apparently never read through to the end where he lashes out: “Stop thinking about your rights, stop demanding things of power.”24

Of the two characters Pasolini places on Etna mentioned thus far, neither one demands anything of constituent power. The Milanese patriarch abandons his stake in production, while the cannibal lives outside law altogether.

As studies of the period have shown, postwar European capitalism, beholden to ideals of full employment, extraction, and consumerism, was an extension of mid-century fascism, rather than its negation. Much cultural production was, as always, implicated in this postcolonial project.25 Furthermore, the postwar Italian left parties’ submission to Stalinism (PCI) and reformist liberalism (PSI) shows that their insistence on productivity was little more than the encouragement of “working-class participation in postwar reconstruction,” as described by Stephen Wright.26 Early dissidents like Raniero Panzieri—one of the intellectual founders of operaismo (workerism)27—were at first permitted to criticize the parties, but were ultimately expelled. Pasolini was also famously expelled in 1949 for moral indignities, including his interest in Sartre, per the Party’s official statement.28 But, as Wright documents, there was a younger generation of socialists, communists, and anarchists who all “agreed that the growing moderation of the left parties and unions sprang first and foremost from their indifference to the changes wrought upon the Italian working class by postwar economic development.”29

The last scene of Theorem certainly followed from debates about overcoming capitalism that played out in Italian left theory from the 1950s onwards. As philosophers and leftists returned to Marx’s writing with less of the baggage of Marxist-Leninist formalism, more militant positions began to develop. While the extent of Pasolini’s support for militancy is up for debate—though he served as a mostly perfunctory editor at the journal of the extra-parliamentary, far-left group Lotta Continua for two months in 1971—it’s no accident that in his 1968 film, his approach to critiquing industrial capitalism was to make it disappear through the figure of the naked patriarch. It’s almost as if he were staging Asor Rosa’s argument in the second issue of Quaderni Rossi six years prior: “The only way to understand the system is through conceiving of its destruction.”30

While many of the postwar Italian thinkers and militants mentioned above turned, for better or worse, to sociological attempts at reading the composition of the working classes, it is not a stretch to include Pasolini in their heterogeneous critiques. Though his politics were certainly not as radical as other thinkers mentioned here, and though his criticisms of the student movement in the ’60s and ’70s sometimes lacked a coherent analysis of class composition, Pasolini’s films merit inclusion in the understanding of this period’s re-reception of Marxism.

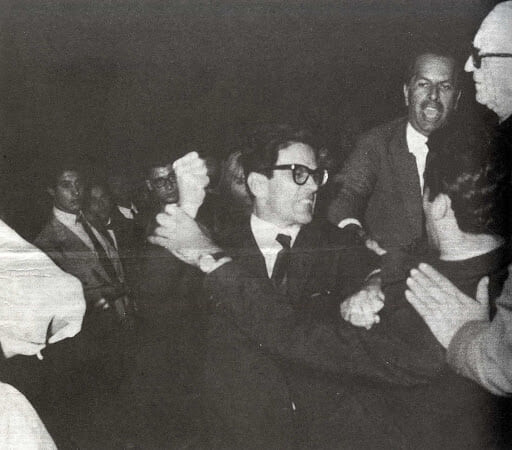

Pasolini punches a young fascist in front of the Quattro Fontane cinema in Rome, 1962.

Leonardo Sciascia’s Candidness

Considering Etna’s presence in writing and stories from the island for millennia, there is surprisingly scant reference to the volcano in the novels and short stories of Leonardo Sciascia, a preeminent twentieth-century Sicilian author and communist. His gorgeous prose, which sometimes falls into the traps of the bourgeoisie communist intellectual, details different areas of Sicily than those already mentioned: parts that are inland, dry, far from the coast.31 Of all his detective stories and anti-mafia noirs written in the 1960s through the ’80s, the most striking in its investigation of postwar Sicilian political life is Candido (1977)—published the same year as a spontaneous rebellion erupted in the North, spearheaded by the extra-parliamentary left and an organic workers’ movements comprised of many laborers from the South. The novel follows the life of an eponymous character plagued by honesty in a land that Sciascia describes elsewhere as one where “a man’s left hand cannot trust the right hand.”32 That same land has also been described by US poet and critic Albert Mobilio—who introduced a collection of Sciascia’s short stories in translation—as “a world where deception is only frowned upon to the degree it lacks artfulness.”33 In that collection, Sciascia sketches this world of artful but tragic scams. In one story, a group of Sicilians who have pawned all their belongings to pay for a one-way ticket to New Jersey find themselves a few hours’ drive away from where they started after eleven days at sea.

In the novel, at first it seems that Candido—an open reference to Voltaire—is a foil to what Sciascia here and elsewhere paints as the corrupt trickster, common to many Sicilian folk stories. One example of this trickster figure is Giufà, a character common across the Mediterranean under different names in Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, and Turkey. In Sicily, he is a “capricious figure … For all his ‘tricks’ and apparent amorality, Giufà is never consciously malicious. Instead this candid young man outwits his superiors because of their own greed, incompetence or abuse of office.”34 However, as the story progresses, it becomes clear that Candido and his honesty are not painted in contrast to the people on the streets trying their best to get by, but rather to bureaucrats in the PCI—themselves tricksters of a sort—and those who lie to better exploit others. Like another Sicilian folk character, Firrazzanu, Candido is a Robin Hood–type, with the caveat that he is born wealthy. When he learns at a tender age that he has inherited property, he cries. “Never had he dreamed that one man could wield power over another which came from money, from land, from sheep, from cattle. And much less that he himself could have such power. When he was home, alone in his room, he wept, he did not know whether from joy or anguish.”35 Indeed, Sciascia intends to connect Candido’s (rare) honesty with collectivist values; in this way the novel can be interpreted as a lament for the postwar individualism that was developing in place of the political militancy of the island’s distant and very recent past.36 Like Pasolini, Candido is expelled from the Communist Party when he contests the local functionary’s sectarianism and offers to give away all his land to the workers who tend his grounds. Unlike the dogmatic Marxist-Leninists and Stalinists around him, “For Candido, being a Communist was a simple fact, like being thirsty and wanting to drink; to him the texts did not matter much.”37

Candido’s only friend is Don Antonio, a priest excommunicated for his interest in psychoanalysis (coded language for Marxism in the Church). Following Candido’s lead, toward the end of the book Don Antonio also begins to take up an anti-sectarian position—strikingly similar to Pasolini’s, in fact. Here, the priest critiques the PCI and the budding student movement in a tone almost identical to Pasolini’s articles and poems of the time:

“The word ‘students’ makes a good Communist reach for his gun, like Dr. Goebbels when he heard the word ‘intellectual.’ But I am not a good Communist.” Yet at times [Don Antonio], too, reached for his gun: “What student leftists have not understood (and could not understand, since their ideas were spawned by the offspring of the middle class) is that you cannot tell a worker who at long last is eating three meals a day that precisely because he is eating regularly he is running the risk of not being revolutionary enough.”38

Both the director and the priest also shared a strained but ultimately functioning relationship with Catholicism, if certainly not with the Church.39 However, elements of Pasolini’s anti-orthodoxy are also visible in Candido, and thus in Sciascia. Like Pasolini, Candido feels at home with the peasants and the workers, in the destitute(d) field—not because either of them venerates workerist fetishes, but because those spaces allow for the possibility of a communistically organized life.

Coda

Pasolini often noted that cinema could make a certain type of “concreteness” in life visible, remarking more than once that film was less susceptible to ideology than other media—even if many of his generation of art-house filmmakers demonstrated that radical formalism could quickly mutate into orthodoxy when guided by market forces, nationalist mythologizing, or Stalinist and Maoist sectarianism. Pasolini seemed to affirm that film can (even if rarely) get away from the ideological function of the image reproduced by the political party, the state, and the commodity fetish, which conspire to render life, work, and desire abstract. In this sense, perhaps he understood the abstraction of quotidian life in a way similar to Althusser, who described Leonardo Cremonini’s “painting of abstraction” (in contrast to abstract painting) as demonstrating “the determinate absence which governs.”40 Or maybe Pasolini saw the lapilli falling from Etna—outlining everything around it in a thin black veil—as negating a different kind of determinate abstraction: of time, but also of value that is produced/extracted in reference to linear time. In his films, however, his goal was less to make abstraction apparent than to find noncapitalist forms of life and desire alive and well in between and despite governing, constituent principles, whether in the subproletariat neighborhoods of Rome, in nonstandard dialects, in Medieval lore, in Catholic ritual, or on Etna.

See a modernized, English translation of Pliny’s two letters to Tacitus here →.

James Mackay, The Invention of Sicily: A Mediterranean History (Verso, 2021), 17–18, 81.

Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 79–80.

The premier example is, of course, The Godfather.

Fernand Braudel, Il Mediterraneo: Lo Spazio, La Storia, Gli Uomini, Le Tradizioni (Bompiani, 2017), 5.

This was before even he began to fall prey to the lusting eye of the European postcolonial and sought to film “real life” in the former colonized worlds. On Pasolini’s “third-worldism,” Gian Liugi Corinto writes that it “was a search for disorientation, of dislocation from the geographical areas where the bourgeoise flourishes and prospers, a search for pure and sincere fragments, scattered far from urban anxieties.” Corinto, L’Etna di Pier Paolo Pasolini (Angelo Pontecorboli Editore, 2020), 18–19. See also Toni Hildebrandt’s “Allegories of the Profane on Foreign Soil in Pasolini’s Work after 1968,” Estetica: Studi e Ricerche 2 (July–December, 2017), where he writes: “Pasolini’s critique of ethnocentrism is therefore threatened by the haste that this same critique rashly seeks to repatriate through translation and equivalence.” Unless otherwise specified, translations from the Italian are my own. Thanks to Ara H. Merjian for pointing my attention to Hildebrandt’s work.

Sebastiano Gesù, “The Desert and the Scream,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini e L’Etna: Il Deserto e il Grido, trans. Ernesto Leotta (40due Edizioni, 2015).

Pasolini shot either all or part of the following films on Etna: The Gospel According to Saint Matthew (1964), Theorem (1968), Pigsty (1969), and The Canterbury Tales (1972).

Ara H. Merjian, “On Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘The Long Road of Sand,’” Bookforum, June 13, 2016 →; Pier Paolo Pasolini, The Long Road of Sand (Contrasto Books, 2015). See also Merjian, Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

On this note, see Jose Rosales, “Disposable-Time as the True Measure of Wealth: Benjamin, Marx, and the Temporal Form of the ‘Real Movement of Abolition’” →. A longer version of the text is forthcoming in 2022.

Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 5.

George Scialabba, “Introduction,” in Leonardo Sciascia, The Day of the Owl, trans. Archibald Colquhoun and Arthur Oliver (New York Review Books, 2003).

Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 5.

Tarì, There is No Unhappy Revolution: The Communism of Destitution (Common Notions, 2021). Thank you to Jose Rosales for pointing my attention to this section of the book, and for sharing his reading of the text with me. For an excerpt from Tarì’s book published in e-flux journal, see →. For a conversation with Rosales, Carla Bottiglieri, Luhuna Carvalho, Giulia Gabrielli, and Matt Peterson about Tarì’s book, see →.

For one recent example of many, see Keti Chukhrov, Practicing the Good: Desire and Boredom in Soviet Socialism (University of Minnesota Press, 2020).

On how Pasolini exiles bourgeois characters and tropes, see Andreas Petrossiants, “Pox Populi,” Artforum, July 16, 2020 →.

I imagine a scene reminiscent of the “progressive” social reformers entering slums in the early twentieth century in industrializing cities in the US, lamenting the immorality of the inner cities, all the while venerating forms of racist, capitalist value production. This hypocrisy is analyzed in Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (Norton, 2019).

Gesù, “The Desert and the Scream,” 33.

Steven Wright, Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism (Pluto Books, 2017), 7.

That much of the (paltry) investment from the North made it into the pockets of the mafia and wealthy politicians through backroom deals while destroying natural landscapes and forms of life without providing economic stability or growth on the island can only euphemistically be called an “oversight.” For the tragedy of federal “investment” in Sicily, see Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 214–15.

Verónica Gago, “Intellectuals, Experiences, and Militant Investigation: Avatars of a Tense Relation,” Viewpoint Magazine, June 6, 2017 →.

Corinto, L’Etna di Pier Paolo Pasolini, 39. Emphasis mine.

Tarì, There is No Unhappy Revolution, 47–49.

See Jaleh Mansoor, Marshall Plan Modernism: Italian Postwar Abstraction and the Beginnings of Autonomia (Duke University Press, 2016). Though I single out Pasolini due to his connection with Etna, two great Italian directors of this period who must be mentioned in this political context are Pietro Eli and Liliana Cavani. The former lampooned the inability of the student movement to speak to the working classes with the brilliant La Classe Operaia Va in Paradiso (1975) and the latter foreshadowed how the carceral apparatus would be mobilized against militants and students with I Cannibali (1971).

Wright, Storming Heaven, 20.

See Mario Tronti, “Our Operaismo,” New Left Review 73 (January–February 2012). Available here →.

Pasolini was expelled from the PCI branch of Pordenone. The statement was published in l’Unita on October 29, 1949. See Corinto, L’Etna di Pier Paolo Pasolini, 15.

In the ’50s, there were dissident readers of Marx all over the country—Luciano Della Mea in Milan, Galvano Della Volpe in Sicily, and in Rome a circle led by Mario Tronti, part of “the PCI’s long-troublesome cell at the university.” Wright, Storming Heaven, 18. Though Pasolini’s interest in Catholicism is mostly in the background of this text, it is interesting to compare his attention to Catholic myth and scripture with some Marxists who came “from dissenting religious families, part of the local Valdese or Baptist communities” in Turin. In the ensuing two decades, thinkers like these went beyond Hegelian appreciations of development, progress, and accumulation to instead articulate “the technical and political aspects of class composition,” to develop post-Marxist notions of autonomy, and in some respects set the stage for the insurrectionary, autonomous, and post-workerist social movements that would characterize Italy’s “hot autumn” and the “years of lead.” See Andrew Anastasi, “A Living Unity in the Marxist: Introduction to Tronti’s Early Writings,” Viewpoint, October 3, 2016 →.

Quoted in Wright, Storming Heaven, 26. The context for the 1961 formation of Quaderni Rossi, a magazine based on workers’ inquiry, also opened the field for analyses of the lives of workers stripped of Stalinist fetish. Initiated by Panzieri and others in Turin, these analyses appropriated capitalist notions of sociology as an antithesis to the cultures of “reformism and Stalinism,” which are “based upon a fatalistic conception of progress and on the premise of a revolution from above” (20). Before this, sociology “was largely confined to studies of the ‘Southern question’ which, apart from the accounts of peasant life by Ernesto De Martino, tended to present themselves primarily as workers of ‘literature’” (19). Wright, Storming Heaven.

Another key work documenting the impoverished interior of the island from an anti-fascist perspective is Elio Vittorini’s Conversations in Sicily (1941), a decidedly modernist novel that follows a Sicilian living in the North as he travels back South to visit his mother. He is unable to live with “abstract furies” spurred by the “massacres in the posters for the newspapers”—those perpetrated by Mussolini’s army in Ethiopia.

Sciascia, quoted in Albert Mobilio, “Introduction,” in Leonardo Sciascia, The Wine Dark Sea, trans. Avril Bardoni (New York Review Books, 2000), xiii.

Mobilio, “Introduction,” xiii.

Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 82–83. Emphasis mine.

Leonardo Sciascia, Candido (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), 45.

Take two representative examples. After the unification of Italy—which can really be described as one Northern royal family’s success in colonizing the entire peninsula, setting the stage for fascism six decades later—promises of local self-rule made to Sicily for its participation in the war for nationhood were not kept, of course. Sicily continued its steady economic decline, purposefully underdeveloped and extracted from by the new centralized state. In the late 1890s, however, a major working-class social movement called the Fasci dei Lavoratori erupted, fighting against the new goliath autocracy. It was violently put down by armies from Rome. Another example: In 1967, when the Communist Party won 21.3 percent of the vote in Sicily, the police and mafia worked together to kill trade-union activists and investigative journalists, instilling fear about worker organizing. Four years later the Communists polled at 12.5 percent. In both cases, working-class power was effectively eviscerated by the ruling classes using corrupt local officials and organized crime. The Church was similarly to blame. The history of the Sicilian Mafia and its collaboration with local and federal officials is too long a story to tell here. See Mackay, Invention of Sicily, 173–238, and John Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: The Rise of the Italian Mafias (Sceptre, 2012).

Sciascia, Candido, 73.

Sciascia, Candido, 123. On Pasolini’s critique of the student movement, see Wu Ming, “The Police vs. Pasolini, Pasolini vs. The Police,” Verso blog, June 29, 2016 →.

In Sicily, the Church was mobilized by many different regimes, from the Inquisition to Mussolini’s fascists, as a form of social control. But Catholic rites and rituals were at times also a form of refusal. As Mackay writes in Invention of Sicily, throughout Spanish rule “the Sicilians experienced a complex process of adaptation and integration which combined public devotion and apparent obedience with private subversion” (108).

Category

Subject

Thanks to Elvia Wilk, Giovanni de Felice, Giulia Sbaffi, Ciara Patten, and Kaye Cain-Nielsen for their thoughts and edits on this text at various stages of completion, and to Pietro Scammacca for first encouraging me to explore Pasolini’s work on Etna. An alternate version of this essay will appear in a future publication by Istituto Sicilia →.