I want you to take out your mobile phone. Open the video. Record whatever you see for a couple of seconds. No cuts. You are allowed to move around, to pan and zoom. Use effects only if they are built in. Keep doing this for one month, every day. Now stop. Listen.

Lets start with a simple proposition: what used to be work has increasingly been turned into occupation.1

This change in terminology may look trivial. In fact, almost everything changes on the way from work to occupation. The economic framework, but also its implications for space and temporality.

If we think of work as labor, it implies a beginning, a producer, and eventually a result. Work is primarily seen as a means to an end: a product, a reward, or a wage. It is an instrumental relation. It also produces a subject by means of alienation.

An occupation is not hinged on any result; it has no necessary conclusion. As such, it knows no traditional alienation, nor any corresponding idea of subjectivity. An occupation doesn’t necessarily assume remuneration either, since the process is thought to contain its own gratification. It has no temporal framework except the passing of time itself. It is not centered on a producer/worker, but includes consumers, reproducers, even destroyers, time-wasters, and bystanders—in essence, anybody seeking distraction or engagement.

Occupation

The shift from work to occupation applies in the most different areas of contemporary daily activity. It marks a transition far greater than the often-described shift from a Fordist to post-Fordist economy. Instead of being seen as a means of earning, it is seen as a way of spending time and resources. It clearly accents the passage from an economy based on production to an economy fueled by waste, from time progressing to time spent or even idled away, from a space defined by clear divisions to an entangled and complex territory.

Perhaps most importantly: occupation is not a means to an end, as traditional labor is. Occupation is in many cases an end in itself.

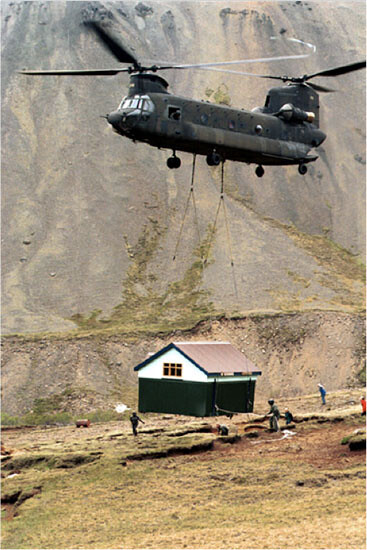

Occupation is connected to activity, service, distraction, therapy, and engagement. But also to conquest, invasion, and seizure. In the military, occupation refers to extreme power relations, spatial complication, and 3D sovereignty. It is imposed by the occupier on the occupied, who may or may not resist it. The objective is often expansion, but also neutralization, stranglehold, and the quelling of autonomy.

Occupation often implies endless mediation, eternal process, indeterminate negotiation, and the blurring of spatial divisions. It has no inbuilt outcome or resolution. It also refers to appropriation, colonization, and extraction. In its processual aspect occupation is both permanent and uneven—and its connotations are completely different for the occupied and the occupier.

Of course occupations—in all the different senses of the word—are not the same. But the mimetic force of the term operates in each of the different meanings and draws them toward each other. There is a magic affinity within the word itself: if it sounds the same, the force of similarity works from within it.2 The force of naming reaches across difference to uncomfortably approximate situations that are otherwise segregated and hierarchized by tradition, interest, and privilege.

Occupation as Art

In the context of art, the transition from work to occupation has additional implications. What happens to the work of art in this process? Does it too transform into an occupation?

In part, it does. What used to materialize exclusively as object or product—as (art) work—now tends to appear as activity or performance. These can be as endless as strained budgets and attention spans will allow. Today the traditional work of art has been largely supplemented by art as a process—as an occupation.3

Art is an occupation in that it keeps people busy—spectators and many others. In many rich countries art denotes a quite popular occupational scheme. The idea that it contains its own gratification and needs no remuneration is quite accepted in the cultural workplace. The paradigm of the culture industry provided an example of an economy that functioned by producing an increasing number of occupations (and distractions) for people who were in many cases working for free. Additionally, there are now occupational schemes in the guise of art education. More and more post- and post-post-graduate programs shield prospective artists from the pressure of (public or private) art markets. Art education now takes longer—it creates zones of occupation, which yield fewer “works” but more processes, forms of knowledge, fields of engagement, and planes of relationality. It also produces ever-more educators, mediators, guides, and even guards—all of whose conditions of occupation are again processual (and ill- or unpaid).

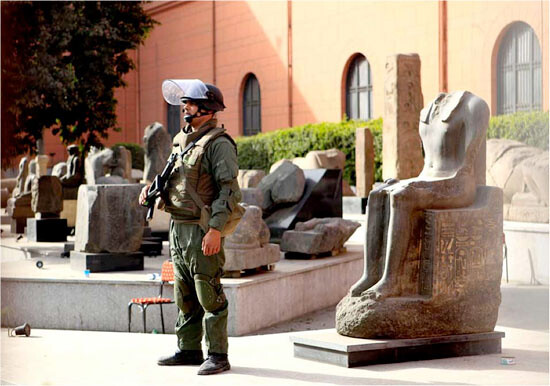

The professional and militarized meaning of occupation unexpectedly intersect here, in the role of the guard or attendant, to create a contradictory space. Recently, a professor at the University of Chicago suggested that museum guards should be armed.4 Of course, he was referring primarily to guards in (formerly) occupied countries like Iraq and other states in the midst of political upheaval, but by citing potential breakdowns of civic order he folded First-World locations into his appeal. What’s more, art occupation as a means of killing time intersects with the military sense of spatial control in the figure of the museum guard—some of whom may already be military veterans. Intensified security mutates the sites of art and inscribes the museum or gallery into a sequence of stages of potential violence.

Another prime example in the complicated topology of occupation is the figure of the intern (in a museum, a gallery, or most likely an isolated project).5 The term intern is linked to internment, confinement, and detention, whether involuntary or voluntary. She is supposed to be on the inside of the system, yet is excluded from payment. She is inside labor but outside remuneration: stuck in a space that includes the outside and excludes the inside simultaneously. As a result, she works to sustain her own occupation.

Both examples produce a fractured timespace with varying degrees of occupational intensity. These zones are very much shut off from one another, yet interlocked and interdependent. The schematics of art occupation reveal a checkpointed system, complete with gatekeepers, access levels, and close management of movement and information. Its architecture is astonishingly complex. Some parts are forcefully immobilized, their autonomy denied and quelled in order to keep other parts more mobile. Occupation works on both sides: forcefully seizing and keeping out, inclusion and exclusion, managing access and flow. It may not come as surprise that this pattern often but not always follows fault lines of class and political economy.

In poorer parts of the world, the immediate grip of art might seem to lessen. But art-as-occupation in these places can more powerfully serve the larger ideological deflections within capitalism and even profit concretely from labor stripped of rights.6 Here migrant, liberal, and urban squalor can again be exploited by artists who use misery as raw material. Art “upgrades” poorer neighborhoods by aestheticizing their status as urban ruins and drives out long-term inhabitants after the area becomes fashionable.7 Thus art assists in the structuring, hierarchizing, seizing, up- or downgrading of space; in organizing, wasting, or simply consuming time through vague distraction or committed pursuit of largely unpaid para-productive activity; and it divvies up roles in the figures of artist, audience, freelance curator, or uploader of cell phone videos to a museum website.

Generally speaking, art is part of an uneven global system, one that underdevelops some parts of the world, while overdeveloping others—and the boundaries between both areas interlock and overlap.

Life and Autonomy

But beyond all this, art doesn’t stop at occupying people, space, or time. It also occupies life as such.

Why should that be the case? Let’s start with a small detour on artistic autonomy. Artistic autonomy was traditionally predicated not on occupation, but on separation—more precisely, on art’s separation from life.8 As artistic production became more specialized in an industrial world marked by an increasing division of labor, it also grew increasingly divorced from direct functionality.9 While it apparently evaded instrumentalization, it simultaneously lost social relevance. As a reaction, different avant-gardes set out to break the barriers of art and to recreate its relation to life.

Their hope was for art to dissolve within life, to be infused with a revolutionary jolt. What happened was rather the contrary. To push the point: life has been occupied by art, because art’s initial forays back into life and daily practice gradually turned into routine incursions, and then into constant occupation. Nowadays, the invasion of life by art is not the exception, but the rule. Artistic autonomy was meant to separate art from the zone of daily routine—from mundane life, intentionality, utility, production, and instrumental reason—in order to distance it from rules of efficiency and social coercion. But this incompletely segregated area then incorporated all that it broke from in the first place, recasting the old order within its own aesthetic paradigms. The incorporation of art within life was once a political project (both for the left and right), but the incorporation of life within art is now an aesthetic project, and it coincides with an overall aestheticization of politics.

On all levels of everyday activity art not only invades life, but occupies it. This doesn’t mean that it’s omnipresent. It just means that it has established a complex topology of both overbearing presence and gaping absence—both of which impact daily life.

Checklist

But, you may respond, apart from occasional exposure, I have nothing to do with art whatsoever! How can my life be occupied by it? Perhaps one of the following questions applies to you:

Does art possess you in the guise of endless self-performance?10 Do you wake feeling like a multiple? Are you on constant auto-display?

Have you been beautified, improved, upgraded, or attempted to do this to anyone/thing else? Has your rent doubled because a few kids with brushes were relocated into that dilapidated building next door? Have your feelings been designed, or do you feel designed by your iPhone?

Or, on the contrary, is access to art (and its production) being withdrawn, slashed, cut off, impoverished and hidden behind insurmountable barriers? Is labor in this field unpaid? Do you live in a city that redirects a huge portion of its cultural budget to fund a one-off art exhibition? Is conceptual art from your region privatized by predatory banks?

All of these are symptoms of artistic occupation. While, on the one hand, artistic occupation completely invades life, it also cuts off much art from circulation.

Division of Labor

Of course, even if they had wanted to, the avant-gardes could never have achieved the dissolution of the border between art and life on their own. One of the reasons has to do with a rather paradoxical development at the root of artistic autonomy. According to Peter Bürger, art acquired a special status within the bourgeois capitalist system because artists somehow refused to follow the specialization required by other professions. While in its time this contributed to claims for artistic autonomy, more recent advances in neoliberal modes of production in many occupational fields started to reverse the division of labor.11The artist-as-dilettante and biopolitical designer was overtaken by the clerk-as-innovator, the technician-as-entrepreneur, the laborer-as-engineer, the manager-as-genius, and (worst of all) the administrator-as-revolutionary. As a template for many forms of contemporary occupation, multitasking marks the reversal of the division of labor: the fusion of professions, or rather their confusion. The example of the artist as creative polymath now serves as a role model (or excuse) to legitimate the universalization of professional dilettantism and overexertion in order to save money on specialized labor.

If the origin of artistic autonomy lies in the refusal of the division of labor (and the alienation and subjection that accompany it), this refusal has now been reintegrated into neoliberal modes of production to set free dormant potentials for financial expansion. In this way, the logic of autonomy spread to the point where it tipped into new dominant ideologies of flexibility and self-entrepreneurship, acquiring new political meanings as well. Workers, feminists, and youth movements of the 1970s started claiming autonomy from labor and the regime of the factory.12 Capital reacted to this flight by designing its own version of autonomy: the autonomy of capital from workers.13 The rebellious, autonomous force of those various struggles became a catalyst for the capitalist reinvention of labor relations as such. Desire for self-determination was rearticulated as a self-entrepreneurial business model, the hope to overcome alienation was transformed into serial narcissism and overidentification with one’s occupation. Only in this context can we understand why contemporary occupations that promise an unalienated lifestyle are somehow believed to contain their own gratification. But the relief from alienation they suggest takes on the form of a more pervasive self-oppression, which arguably could be much worse than traditional alienation.14

The struggles around autonomy, and above all capital’s response to them are thus deeply ingrained into the transition from work to occupation. As we have seen, this transition is based on the role model of the artist as a person who refuses the division of labor and leads an unalienated lifestyle. This is one of the templates for new occupational forms of life that are all-encompassing, passionate, self-oppressive, and narcissistic to the bone.

To paraphrase Allan Kaprow: life in a gallery is like fucking in a cemetery.15 We could add that things become even worse as the gallery spills back into life: as the gallery/cemetery invades life, one begins to feel unable to fuck anywhere else.16

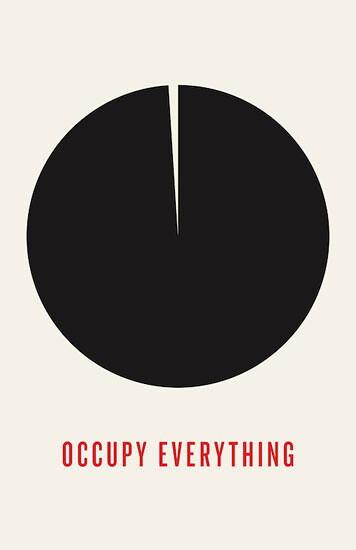

Poster for the Occupy Movement, 2011.

Occupation, Again

This might be the time to start exploring the next meaning of occupation: the meaning it has taken on in countless squats and takeovers in recent years. As the occupiers of the New School in 2008 emphasized, this type of occupation tries to intervene into the governing forms of occupational time and space, instead of simply blocking and immobilizing a specific area:

Occupation mandates the inversion of the standard dimensions of space. Space in an occupation is not merely the container of our bodies, it is a plane of potentiality that has been frozen by the logic of the commodity. In an occupation, one must engage with space topologically, as a strategist, asking: What are its holes, entrances, exits? How can one disalienate it, disidentify it, make it inoperative, communize it?17

To unfreeze the forces that lie dormant in the petrified space of occupation means to rearticulate their functional uses, to make them non-efficient, non-instrumental, and non-intentional in their capacities as tools for social coercion. It also means to demilitarize it—at least in terms of hierarchy—and to then militarize it differently. Now, to free an art space from art-as-occupation seems a paradoxical task, especially when art spaces extend beyond the traditional gallery. On the other hand, it is also not difficult to imagine how any of these spaces might operate in a non-efficient, non-instrumental, and non-productive way.

But which is the space we should occupy? Of course, at this moment suggestions abound for museums, galleries, and other art spaces to be occupied. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that; almost all these spaces should be occupied, now, again, and forever. But again, none of these spaces is strictly coexistent with our own multiple spaces of occupation. The realms of art remain mostly adjacent to the incongruent territories that stitch up and articulate the incoherent accumulation of times and spaces by which we are occupied. At the end of the day, people might have to leave the site of occupation in order to go home to do the thing formerly called labor: wipe off the tear gas, go pick up their kids from child care, and otherwise get on with their lives.18 Because these lives happen in the vast and unpredictable territory of occupation, and this is also where lives are being occupied. I am suggesting that we occupy this space. But where is it? And how can it be claimed?

The Territory of Occupation

The territory of occupation is not a single physical place, and is certainly not to be found within any existing occupied territory. It is a space of affect, materially supported by ripped reality. It can actualize anywhere, at any time. It exists as a possible experience. It may consist of a composite and montaged sequence of movements through sampled checkpoints, airport security checks, cash tills, aerial viewpoints, body scanners, scattered labor, revolving glass doors, duty free stores. How do I know? Remember the beginning of this text? I asked you to record a few seconds each day on your mobile phone. Well, this is the sequence that accumulated in my phone; walking the territory of occupation, for months on end.

Walking through cold winter sun and fading insurrections sustained and amplified by mobile phones. Sharing hope with crowds yearning for spring. A spring that feels necessary, vital, unavoidable. But spring didn’t come this year. It didn’t come in summer, nor in autumn. Winter came around again, yet spring wouldn’t draw any closer. Occupations came and froze, were trampled under, drowned in gas, shot at. In that year people courageously, desperately, passionately fought to achieve spring. But it remained elusive. And while spring was violently kept at bay, this sequence accumulated in my cell phone. A sequence powered by tear gas, heartbreak, and permanent transition. Recording the pursuit of spring.

Jump cut to Cobra helicopters hovering over mass graves, zebra wipe to shopping malls, mosaic to spam filters, SIM cards, nomad weavers; spiral effect to border detention, child care and digital exhaustion.19 Gas clouds dissolving between high-rise buildings. Exasperation. The territory of occupation is a place of enclosure, extraction, hedging, and constant harassment, of getting pushed, patronized, surveilled, deadlined, detained, delayed, hurried—it encourages a condition that is always too late, too early, arrested, overwhelmed, lost, falling.

Your phone is driving you through this journey, driving you mad, extracting value, whining like a baby, purring like a lover, bombarding you with deadening, maddening, embarrassing, outrageous claims for time, space, attention, credit card numbers. It copy-pastes your life to countless unintelligible pictures that have no meaning, no audience, no purpose, but do have impact, punch, and speed. It accumulates love letters, insults, invoices, drafts, endless communication. It is being tracked and scanned, turning you into transparent digits, into motion as a blur. A digital eye as your heart in hand. It is witness and informer. If it gives away your position, it means you’ll retroactively have had one. If you film the sniper that shoots at you, the phone will have faced his aim. He will have been framed and fixed, a faceless pixel composition.20 Your phone is your brain in corporate design, your heart as a product, the Apple of your eye.

Your life condenses into an object in the palm of your hand, ready to be slammed into a wall and still grinning at you, shattered, dictating deadlines, recording, interrupting.

The territory of occupation is a green-screened territory, madly assembled and conjectured by zapping, copy-and-paste operations, incongruously keyed in, ripped, ripping apart, breaking lives and heart. It is a space governed not only by 3D sovereignty, but 4D sovereignty because it occupies time, a 5D sovereignty because it governs from the virtual, and an n-D sovereignty from above, beyond, across—in Dolby Surround. Time asynchronously crashes into space; accumulating by spasms of capital, despair, and desire running wild.

Here and elsewhere, now and then, delay and echo, past and future, day for night nest within each other like unrendered digital effects. Both temporal and spatial occupation intersect to produce individualized timelines, intensified by fragmented circuits of production and augmented military realities. They can be recorded, objectified, and thus made tangible and real. A matter in motion, made of poor images, lending flow to material reality. It is important to emphasize that these are not just passive remnants of individual or subjective movements. Rather, they are sequences that create individuals by means of occupation. They trigger full stops and passionate abandon. They steer, shock, and seduce.

Look at your phone to see how it has sampled scattered trajectories of occupation. Not only your own. If you look at your phone you might also find this sequence: Jump cut to Cobra helicopters hovering over mass graves, zebra wipe to shopping malls, mosaic to spam filters, SIM cards, nomad weavers; spiral effect to border detention, child care and digital exhaustion. I might have sent it to you from my phone. See it spreading. See it become invaded by other sequences, many sequences, see it being re-montaged, rearticulated, reedited. Let’s merge and rip apart our scenarios of occupation. Break continuity. Juxtapose. Edit in parallel. Jump the axe. Build suspense. Pause. Countershoot. Keep chasing spring.

These are our territories of occupation, forcefully kept apart from each other, each in his and her own corporate enclosure. Let’s reedit them. Rebuild. Rearrange. Wreck. Articulate. Alienate. Unfreeze. Accelerate. Inhabit. Occupy.

I am ripping these ideas from a brilliant observation by the Carrot Workers Collective. See →

Walter Benjamin, “Doctrine of the Similar,” in Selected Writings, Vol. 2, part 2, 1931-1934, ed. Michael Jennings, Howard Eiland, Gary Smith. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 694-711, esp. 696.

One could even say: the work of art is tied to the idea of a product (bound up in a complex system of valorization). Art-as-occupation bypasses the end result of production by immediately turning the making-of into commodity.

Lawrence Rothfield as quoted in John Hooper, “Arm museum guards to prevent looting, says professor,” The Guardian, 10.07.2011, “Professor Lawrence Rothfield, faculty director of the University of Chicago’s cultural policy center, told the Guardian that ministries, foundations and local authorities “should not assume that the brutal policing job required to prevent looters and professional art thieves from carrying away items is just one for the national police or for other forces not under their direct control”. He was speaking in advance of the annual conference of the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art (ARCA), held over the weekend in the central Italian town of Amelia. Rothfield said he would also like to see museum attendants, site wardens and others given thorough training in crowd control. And not just in the developing world.” See →.

Carrot Workers Collective, “The figure of the intern appears in this context paradigmatic as it negotiates the collapse of the boundaries between Education, Work and Life.” See →.

As critiqued recently by Walid Raad in the building of the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim franchise and related labor issues. See →.

Central here is Martha Rosler’s three-part essay,“Culture Class: Art, Creativity, Urbanism,” in e-flux journal 21 (December 2010); 23 (March 2011); and 25 (May 2011). See →.

These paragraphs are entirely due to the pervasive influence of Sven Lütticken’s excellent text “Acting on the Omnipresent Frontiers of Autonomy” in To The Arts, Citizens! (Porto: Serralves, 2010), 146-167. Lütticken also commissioned the initial version of this text, to be published soon as a “Black Box” version in a special edition of OPEN magazine.

The emphasis here is on the word obvious, since art evidently retained a major function in developing a particular division of senses, class distinction and bourgeois subjectivity even as it became more divorced from religious or overt representational function. Its autonomy presented itself as disinterested and dispassionate, while at the same time mimetically adapting the form and structure of capitalist commodities.

The Invisible Committee lay out the terms for occupational performativity: “Producing oneself is about to become the dominant occupation in a society where production has become aimless: like a carpenter who’s been kicked out of his workshop and who out of desperation starts to plane himself down. That’s where we get the spectacle of all these young people training themselves to smile for their employment interviews, who whiten their teeth to make a better impression, who go out to nightclubs to stimulate their team spirit, who learn English to boost their careers, who get divorced or married to bounce back again, who go take theater classes to become leaders or “personal development” classes to “manage conflicts” better—the most intimate “personal development,” claims some guru or another, “will lead you to better emotional stability, a more well directed intellectual acuity, and so to better economic performance.” The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (New York: Semiotexte(e), 2009), 16.

Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

It is interesting to make a link at this point to classical key texts of autonomist thought as collected in Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, ed. Sylvere Lotringer and Christian Marazzi (New York: Semiotext(e), 2007).

Toni Negri has detailedthe restructuring of the North Italian labor force after the 1970s, while Paolo Virno and Bifo Berardi both emphasize that the autonomous tendencies expressed the refusal of labor and the rebellious feminist, youth,and workers movements in the ‘70s was recaptured into new, flexibilized and entrepreneurial forms of coercion. More recently Berardi has emphasized the new conditions of subjective identification with labor and its self-perpetuating narcissistic components. See inter alia Toni Negri, i: “Reti produttive e territori: il caso del Nord-Est italiano,” L’inverno è finito. Scritti sulla trasformazione negata (1989–1995), ed. Giovanni Caccia (Rome: Castelvecchi, 1996), 66–80; Paolo Virno, “Do you remember counterrevolution?,” in Radical thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, ed. Michael Hardt and Paolo Virno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996); Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy (New York: Semiotext(e), 2010.

I have repeatedly argued that one should not seek to escape alienation but on the contrary embrace it as well as the status of objectivity and objecthood that goes along with it.

In “What is a Museum? Dialogue with Robert Smithson,” Museum World no. 9 (1967), reprinted in The Writings of Robert Smithson, Jack Flam ed. (New York University Press: New York, 1979), 43-51.

Remember also the now unfortunately defunct meaning of occupation. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries “to occupy” was a euphemism for “have sexual intercourse with,” which fell from usage almost completely during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Inoperative Committee, Preoccupied: The Logic of Occupation (Somewhere: Somebody, 2009),11.

In the sense of squatting, which in contrast to other types of occupation is limited spatially and temporally.

I copied the form of my sequence from Imri Kahn’s lovely video Rebecca makes it!,where it appears with different imagery.

This description is directly inspired by Rabih Mroue’s terrific upcoming lecture “The Pixelated Revolution” on the use of mobile phones in recent Syrian uprisings.

Category

Subject

This text is dedicated to comrade Şiyar. Thank you to Apo, Neman Kara, Tina Leisch, Sahin Okay, and Selim Yildiz.