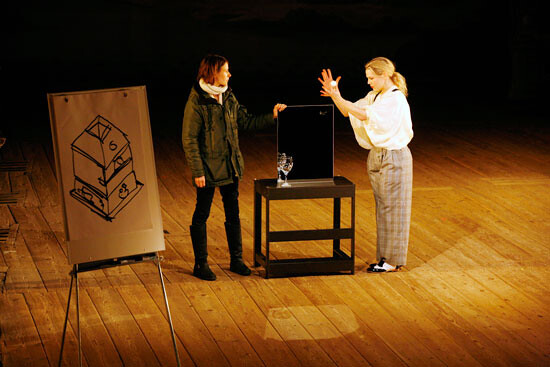

At the end of it all, the Queen defecates—gold bars. The queen in question is Her Britannic Majesty Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (and quite a few other places beside), but here she is presented more simply as the “Queen of England,” just like the woman she has been conversing with through the short performance. That woman too is a Queen Elizabeth, or better still, was, since she died in 1603. As befits the dead, perhaps, she doesn’t actually talk. Her image stares down at the second, living queen.

We are in Derry-Londonderry, a city with one and a half names in a place that has three: Northern Ireland, Ulster, the Five Counties, a place that is a country alongside the other three countries of the United Kingdom, but also a part of another country, Ireland; a place that is not British—unless you are a staunch Unionist—but is rather awkwardly joined to “Great” Britain by the copula “and”; at once united kingdom and asymmetrical duality. That the Queen in this script, the living queen, that is, the one represented by a local actress, Eleanor Methven, is the Queen of England is no accident.1 This is not to say that in Northern Ireland all life, or even all politics, can be reduced to the Troubles and their aftermath, but the convulsions of the financial crisis and their aftermath cannot, perhaps, be read in this place without reference to its troubling constitutional situation—troubling, that is, especially for those who yearn for a world with clear lines of demarcation.

The script has been written by a local playwright, Jimmy McAleavey, and was commissioned by the Swedish artists Goldin+Senneby. The performance itself is exemplary of, and a product of, the kind of division of labor that makes the panegyrists of Global Capitalism drool: funding for the performance itself comes from the profits generated by an algorithmic trading program constructed and implemented by a computer scientist in the US known only as “Ybodon,” on the basis of a design suggested by myself, an anthropologist and former equity fund manager.

The profits are modest, enough to pay the performer for a handful of performances. Still, that the algorithm made any money at all strikes me, the “expert” who proposed the underlying trading strategy, as near miraculous. What did I know about algorithmic trading? My limited expertise is in stock market investing based on so-called “fundamental research” into the business positions and financial strength of the companies whose shares we used to purchase on behalf of our clients. All the same, financial markets, despite the intimidating apparatus of “scientific” knowledge production deployed by experts purporting to explain them, are in some respects quite simple.

The artists’ commission did not require us to develop a strategy that no one else had yet dreamt up, merely one that would preferably make some money while making an important point about contemporary finance: the way in which its workings are analogous to the old, long discredited alchemy. For the Derry performance I proposed an algorithm based on Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP), involving buying stock in a number of large US banks at below their daily VWAP and selling them when they rise above it, making use therefore of the well-attested phenomenon of mean reversion. That is, in the absence of significant newsflow, shares tend to trade in a fairly regular pattern around an average price.

How the algorithm actually bought and sold the shares, I cannot really explain. The computer scientist informed me that it would be a simple “Python script,” but a Python script is no more intelligible to me (nor to many others) than the pronouncements of the Pythoness at Delphi.2

Thematically speaking, Elizabeth II remonstrating with a portrait of her forebear Elizabeth I has little to do with algorithmic trading. In the script, however, the present queen complains that her money, printed by the Bank of England and stamped with her image, is worthless, because not real, merely a conjuring trick depending on the appearance of her likeness thereon. She harangues the old queen, complaining that her ancestor had made use of a “conjuror,” the noted alchemist John Dee. References to Dee’s coining of the expression “British Empire” are mixed in with references to the power of Elizabeth II’s money in commanding soldiers’ loyalty during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The living queen berates the dead one, calling her a “money-grubbing bitch,” in league with the alchemist to “turn freshly discovered earth into gold” by means of the Muscovy Company.3 Yet for all her contempt for alchemy, troubled by the apparent unreality of her own money, she cries out: “Oh, Dee, Dee, I need your magic now!”

Dee’s cosmic visions, at once mathematical, mystical, and sectarian, figured Elizabeth I as the righteous Protestant descendant of King Arthur, engaged in a struggle for world domination with malevolent “Hispano-Papists,” a sectarian imaginary that continues to resonate in the Northern Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth II. And in the background lies the figure of August Nordenskiöld, invoked by Goldin+Senneby in their design for the VWAP assemblage: an eighteenth-century alchemist trying to make gold from base metal to fund the king of Sweden’s wars with Russia, while surreptitiously hoping that the same transmutation will end “the tyranny of money” forever.

The suggestion, then, is that the opaque operations of an algorithm in financial markets cannot be separated either from the ebb and flow of British imperial power in Northern Ireland, or from wider questions of domination, inequality, and injustice, worldwide and historically; that all these questions are bound up with the troubling nature of money and value, those non-identical twins whose origin is obscure, whose very reality is often contested, and yet whose effects in the world are all too tangible.

Characterizations of contemporary finance as esoteric and occult abound. For the most part, these references are casual ones, but the sheer pervasiveness of these understandings, of the vocabulary of alchemy and sorcery, should give us pause and provoke us to ask why these metaphors have become sedimented in our language. In its invocation of alchemy, the VWAP assemblage (of which this article is a belated part) provides not merely a critique of the entanglement of finance and imperial power, but also an entry point into a warren of alternatives, insofar as it insists that modern money and finance are magical after all, and that this magical quality is not something to shy away from or decry.

Finance as Occult

What is it about the activities of financiers or the dynamics of financial markets that incites this linguistic response? In general, when we talk of this occult imagery we are referring to a public imaginary, where finance is scrutinized from outside, but it is revealing that from time to time accounts of finance, or some particular aspect thereof, authored by financial market practitioners themselves, also resort to this vocabulary. Usually the emphasis in these cases is on how the complexity of markets is not amenable to a simple rational analysis and explanation, however impressive the apparatus of economic thought built up around them.

A first example comes in the form of a “biography” of money by a London-based debt fund manager, Felix Martin. Critical of dominant approaches to money in economics, his work is haunted by the occult. “The great temptation,” he writes, “has always been to think that coins and other currency, being tangible and durable, are money—on top of which the magical, incorporeal apparatus of credit and debt is constructed. The reality is exactly the opposite.”4

Elsewhere he quotes Braudel to describe the exchange of bills at early modern European fairs as “a difficult cabala to understand,” or describes Locke’s argument in defense of silver as “at best a confusion and at worst a typical City smokescreen designed to conceal some no-good trickery.”5 The ancient Greek notion of value on which money was built was “an invisible substance that was both everywhere and nowhere”6; the vast network of special purpose vehicles created during the boom in the securitization of debt prior to the financial crisis, known as “shadow banking,” is said to have discovered “a miraculous new means of creating money”7; Martin, not entirely convincingly, concludes that occult metaphor is “an euphemism. No transformation takes place—alchemy is as impossible in banking as in the natural sciences.”8

A second example comes from a more notorious figure: billionaire speculator, investor, and political reformer George Soros argues that financial economics has failed to understand that it is part of the world it only purports to observe, and that as a result the picture of the “real world” it gives in fact distorts that reality. Investors in financial markets are not driven by “rational expectations,” whatever the dominant theory might say, and markets, rather than being efficient, are characterized by “self-validating feedback loops” and cycles of boom and bust. Economics can have no predictive validity for such markets, and if it has no predictive validity, it cannot therefore be a science. He proposes to replace this “science” with what he calls “the alchemy of finance,” a form of knowledge that jettisons the key assumptions of neoclassical economics with respect to finance, namely that investors are rational individuals with identical expectations about the future seeking to maximize profits, a situation that is supposed to lead to markets that are “efficient” and in equilibrium.9

This imagery of the magical and the occult is by no means as unequivocally negative as it may appear to common sense. The most striking example is Soros’s attempt, in the context of a critique of the epistemology of economics, to recuperate the term “alchemy” for his own generation of knowledge about financial markets. More generally, “magic” in English is a readily accessible way of describing the positive, special, or beautiful characteristics of things, events, or processes that defy explanation of their exceptional nature. Thus English speakers talk of a “magical” evening, ceremony, or trip, in such a way that the memory of this magical event is imbued with a sense of romance and mystery, even awe.

In the case of, say, Felix Martin’s use of occult metaphors to gloss the process of maturity transformation in banking, there is something more admiring: if not quite as strong as “isn’t this wonderful?,” certainly, while asking us to remain vigilant, as positive as “the impressive thing about this is that it works, mostly, even though when you look carefully it doesn’t really work at all.”

This ambivalent quality of the occult, and especially of the uses of magic and alchemy, is something we ought to bear in mind: as we shall see, it resembles, and partakes in, the dual character of reality itself, which is simultaneously real and not so. This is why above I wrote that Martin’s dismissal of alchemy as euphemistic was “not entirely convincing.” Take maturity transformation, for example. Banks borrow money from their customers, in the form of the money we deposit in our accounts. They lend it to other customers. They (sometimes) pay interest to their depositors, and charge interest to their debtors. The latter is (or should be) higher than the former, whence a profit. The trouble is that most deposits have a short time horizon: we can deposit money one day and take it out the next, whereas loans are usually paid back over several years, or even decades in the case of mortgages. As long as the bank’s income from slow maturing loans is greater than what it pays to depositors, there is no problem: maturity transformation appears to happen, as short-term liabilities (deposits) appear to be turned into long-term assets (loans). If the value of the bank’s assets crashes, for example, as during the financial crisis, or if depositors lose confidence and rush to withdraw their funds, then the bank may become insolvent: maturity transformation appears to have been mere appearance all along.

Maturity transformation appears to happen, but really does not: this is a classically Western dualism, opening the way to a demystification of appearances through a demonstration of how reality really works. It cannot accept the possibility that both appearance and reality are reality, that maturity transformation does take place because its effects are felt in the world, crystallized in bank accounts, reflected in the loans received and the payments made by clients. What if we were to accept that this process does take place in the same way as the occult takes place, as a technique for bringing something about in the world, even if the explanations and justifications given for these effects are not supported by the investigations of what used to be called “natural philosophy”?

The etymology of a term shared by occult specialists and economists points us in this direction: the former “cast” spells and horoscopes, while the latter “forecast” market trends and key economic indicators. That to cast formerly meant “to reckon, calculate” is no accident. Both “casters” and forecasters deal with conditions which can never be understood in their entirety, futures whose course may be roughly predictable based on prior experience (whether this experience is analyzed statistically or not), but which invariably deliver, sooner or later, the unanticipated and disruptive, showing how knowledge as it has hitherto been configured is incomplete and inadequate.

Agency and Control

First of all, at the heart of the occult are questions of agency and control. The anthropologist Galina Lindquist worked, in the 1990s, with street traders from Moscow, at a time when the glories of the ideology of “free markets” and the shock doctrines of neoliberalism were rendering the lives of millions of former Soviet citizens extremely precarious. For example, one woman struggled to survive as a trader while confronting the dual threats of organized crime and bribe-taking state police. This woman regularly visited a magus seeking assistance to help her modest business flourish amid these twin menaces. The magus’ aim was, by using appropriate magical techniques, to uncover and rectify the trader’s “negative karma,” thereby opening her “money channel” and allowing her to turn a profit. Lindquist’s interpretation, following Bourdieu, is that magic here was a form of action on a world where other means were insufficient, where trust between business partners or between entrepreneurs and state officials is lacking, where cold calculations of risk are nullified by a world that is simply too uncertain for them to be of any use: instead a hope that the future will be kind, or “ungrounded faith in good outcomes” is nourished by magic, part of the local “logic of practice.”10

Magic in this context is a rational technique, just as (to take a classic ethnographic example) magic spells had been rational horticultural techniques for the Trobriand Islanders: as techniques, magical practices are rule-based, supported by a wider epistemic apparatus, and oriented to the production of certain desirable and observable outcomes: “phenomenal attempts to secure control in situations of uncertainty.”11

Cynicism aside, international capital markets at first sight seem to follow logics that are quite different from early neoliberal Russia. In such a setting, unlike in Moscow of the 1990s, relationships between market participants, clients, and regulators are supported by legal sanctions and the coercive authority of the state. In such circumstances, risk, generally understood as the probabilistic measurement of volatility and the threats it poses to earning an acceptable investment return (but also the opportunities it offers), becomes a key technique of evaluation and intervention.

Techniques of risk measurement, like magic spells, are rational techniques for dealing with and acting upon an unpredictable world. These are techniques whose efficacy is supported by science rather than superstition, and under normal circumstances, they appear to work and enable the generation of substantial profits for those who deploy them. Yet the expression “normal circumstances” is crucial here. These are rational techniques which, for all their undoubted mathematical sophistication, do from time to time fail.

The neatest example of this is the Black-Scholes-Merton theory of options pricing, which purported to calculate the prices of options as an objective economic reality, but which instead produced a convergence between its predicted prices and actual market prices in the 1970s and 1980s, before failing during the 1987 stock market crash, a moment of “counter-performativity,” since when it continues to be studied and used, but alongside other models and calculations of price, none of them entirely satisfy.12

When we come to the credit derivatives at the heart of the 2007–9 crisis, the models involved were constructed by investment bank employees with advanced mathematical training, not by economists (like Scholes and Merton) who would go on to win the Nobel Prize. Importantly, these individuals themselves expressed skepticism with regard to the efficacy of a key family of models, the Gaussian copula, but the models continued to work—enabling profit generation, the continued employment of large numbers of well-remunerated employees, and coordination between different internal bank functions—until they too encountered conditions with counter-performative consequences.13

In circumstances they were not designed for, in conditions which they had failed to predict or adequately factor into their models, these techniques are of no more value than horticultural incantations or exorcisms of negative karma—of less value, no doubt—even if they are (but this is just like magic!) backed up by an impressive and internally coherent body of knowledge as to how and why they function. Far from being universally valid, scientific predictions contain in themselves a kind of performative magic effective only when certain conditions obtain. Sometimes, as in the case of options and the ’87 crash, practitioners are more or less convinced of the correspondence between their models and market realities; sometimes, as in the case of credit derivatives, they are less convinced, and can see the role of their techniques in not merely describing, but constructing, the world they inhabit. In both cases, an uncertain future is brought under control, brought through rational techniques into the world of statistically analyzable risks, before irrupting spectacularly into this controlled world and challenging the efficacy of these techniques. Specialists of both occult practices and financial mathematics must either learn to cope with these challenges, or see the authority of their knowledge undermined.

Secrecy and Publicity

The second element of the shared logic of the occult and of finance involves secrecy and publicity. Anthropologists working on magic and witchcraft are frequently told by occult specialists that if they want to be fully informed on the subject, they ought to speak to someone else, someone who “really knows” all about it, but such a person is never forthcoming: the occult defers all attempts to render it transparent. Part of its effectiveness stems from this secrecy and mystery.

Magical techniques, wrote anthropologist Alfred Gell—comparing the effects of magic and art—benefit from “the power that technical processes have of casting a spell over us so that we see the real world in an enchanted form.”14 Art, he suggests, is a technical process, because its “beautiful” artifacts are, unlike a sunset, manufactured. Even Duchamp’s famous urinal, he argues, by virtue of being in an exhibition with the artist’s name attached, participates in this “essential alchemy of art, which is to make what is not out of what is, and to make what is out of what is not.”15 Immanent to all technical processes is a process of enchantment: as spectator of the process, or of its end result, an artifact or art object, I ask, with wonder, “How can that be done? How does it work?” I struggle to grasp “their coming-into-being as objects in the world,” because the technical process transcends my understanding, and therefore I am forced to construe it as magical.16 This process may fail, in which case it can provoke a devastating reaction, but when it works, artworks “dazzle” those who view them, convincing them that something occurs that is not purely technical.

Gell does not consider finance as such, but he does make a pointed remark about magic in contemporary industrial societies. We may think we are, in our quest for improvement and economic growth, comparing different technical means against one another, but behind this is a “magic standard,” the myth of “costless production,” one which ignores the off-balance-sheet costs, from mass unemployment to environmental degradation, of the endless search for perfect efficiency. In the two decades since he wrote, finance has increasingly become the technical means par excellence for achieving this magical perfect efficiency, its hegemony interrupted but not at all ended by the financial crisis. Moreover, finance is every bit as opaque as the most “dazzling” work of art, opaque not only to nonspecialists, but even to those supposed to be overseeing and guiding it, the bank chief executives, shareholders, financial regulators, economists, and politicians who failed to foresee the eruption of the great crisis. Finance is obscure but equipped with powerful agentive force, a quintessential technology of enchantment.

It is true that, in some sense, financial market practitioners, prompted in part by regulation, often aim for transparency: of the kind provided by the publication of interest rates, or market indices, or long regulatory disclosures; markets are, the theory tells us, all about providing accurate and timely and freely available information: the closer we approach this ideal, the better or more efficiently markets function, and the more efficient they are, the better for all of us. Yet how many of us really understand how interest rates come to be? And even those of us who do understand (or think we do) can be blindsided by something like the manipulation of LIBOR by traders from major banks—and manipulation is a classically occult form of agency. Or take stock market indices: readily explicable as numbers which reflect the valuation of their component companies weighted according to the relative sizes of those companies, they “point” to the valuation the stock market places on those companies at any given time. These are commonly taken as the markets themselves, announced as such by fund managers in reports to clients and by newscasters to the general public on the evening news; they are taken to be indicators of the health of the economy, as the economy itself—and all the judgments and assumptions required to manufacture them are obscured by the elegance of a single number.

Financial markets depend on precisely this transparency, the immediacy of a number, behind which further information is less accessible. The fact that there is no shortage of expert explanation available for how these things work does not diminish their enchanting effect. Yet a mismatch between what Gell, talking of art, called the “magical agency” of the artwork (or the financial product), and the “human agency” of the spectator, persists: I may understand how a collateralized debt obligation works, but I couldn’t make one at home.

And while Gell is enthusiastic about the “dazzle effect” of artworks on the spectator, when it comes to financial products this dazzling has a whole host of negative consequences too: from drawing into Wall Street bright young graduates whose talents might better be employed elsewhere, to making public, political, media, and even regulatory scrutiny of particular derivative products or specific financial firms difficult, if not impossible.

We can take Gell’s reflections further: Is there something in the glare of the magical agency of our financial systems that is akin to what Michael Taussig described as the “public secret,” that which everyone knows but no one articulates? And which, even if articulated, is all the same not destroyed? Just as the Enlightenment destroyed magic, but rests on a magic of its own, so too finance, through its rationality—the force of its numbers, the logical brilliance of its algorithms—destroys earlier, nonrationalized understandings of how value is created, and yet finance’s public—regulators, legislators, critics, the public, us—continues to be dazzled by it.17 Finance exercises a tremendous agency, even subsequent to the financial crisis and numerous denunciations and demystifications of its operations.

David Graeber has written of money’s emergence through a dialectic of visibility and invisibility. Most objects used for money, he argues, were also used as adornment for the body, and meant to be seen as a demonstration of their power in the present to onlookers: gold, silver, Kula shells (in the Trobriand Islands and their vicinity), Kwakiutl coppers (in the Pacific Northwest), Maori axes. It is no accident that “specie” derives from the Latin root meaning “to be seen” (“speculation” likewise). People adorned in striking ways, that is to say, meant to be seen, exercise power through this visual display: they summon us to treat them with respect because their adornments are evidence of them having been treated the same way in the past. Money, on the other hand, emerges from this visual display through abstraction: used as a medium of exchange, it exercises a kind of power that is oriented toward the future, because it represents the potential for future exchange. The future is invisible, and as a consequence money is endowed with a magical, mysterious, often dangerous potency.18

When it comes to modern paper money, Graeber notes, something of the specificity of earlier forms is lost: dollar bills are all (more or less) alike, anonymous, invisible at least as specific objects; a fortiori the electronic money, visible only as dull numbers on a screen, which accounts for the bulk of money today. Yet this money is often realized in highly visible, spectacular form: those possessing vast amounts of it buy mansions and yachts, even as millions, billions indeed, of others struggle to figure out how this money is created in the first place, or why it accrues so overwhelmingly to such a small number of people. Tellingly, ethnographic examples from other authors draw links between this dialectic of visibility and invisibility, the operations of capital in a postcolonial and neoliberal world, and the occult. Thus in South Africa in the 1990s, observed Jean and John Comaroff, there was a marked upsurge in accusations of witchcraft as certain members of the post-apartheid society acquired wealth quickly and spent it spectacularly, without it being clear how they were able to do so, even as most people continued to struggle to make do in conditions of great precariousness.19

Money also has this dazzling force at its heart; it is a phenomenon at once public and secret. Recall in The Queen’s Shilling the frustration of Elizabeth II at the unrealness of money, of the Bank of England notes whose value seemingly derived magically from the simple fact of her image appearing thereon. Money is visible: excreted as gold, scattered over the stage in the form of (fake) Bank of England notes. Yet it is also invisible, mysterious: produced through alchemy, through the opaque workings of financial markets, the obscure functioning of the royal digestive system.

Perhaps the VWAP performance’s greatest sleight of hand is that, even as it explains that it is in part funded through algorithmic trading, this source of money is barely touched upon by the script of the performance; still less are its operations, the “how on earthness” of its generation of a surplus, explained. Money is made visible not as money, but in terms of what it can do. The brilliance of the design lies in this act of obscuring: the assemblage’s ability to dazzle resides not just in the “surface” performance but in the hidden performance of the algorithm too. It is as if we are being incited to ask whether finance, however transparent it might be made through regulation and public scrutiny, is not inherently obscure.

Of Reality and Unreality

Finally, in both capital markets and in the worlds of occult practice we are dealing with the play of the real and the imaginary, or the real and the unreal. The primary connotation of the real, or reality, here is that which is substantial, physical, tangible, enduring, as opposed to that which merely seems to be the case, but is eventually revealed to be insubstantial, chimerical, intangible, liable to vanish into thin air. Part of the considerable traction stems from its strong resonance with common sense: what is real is good, what is not real is dangerous and deceptive. There is a strongly moral tone in this framing: what is real is wholesome, desirable; what is not real is a trick, fraudulent, to be unmasked or avoided.

Advocates of radical reform talk of aiding the “real economy,” for instance by directing bank loans to the small businesses which supposedly constitute it, as opposed to the (by implication) unreal world of transnational high finance. By using “real” in this manner they are tapping into an ontology which is shared with the discipline of economics itself, which talks of the “real” economy as opposed to the “financial” economy, or “real” and “financial” assets, as well as “real” as opposed to “nominal” prices. Dig down beneath what appears to be the price, and you will find the real price, that is to say, adjusted for inflation. This opposition goes a long way back. With its origins in late medieval Scholastic theology and the competing ontologies of realism and nominalism, it was already centuries old when Adam Smith talked of real and nominal prices in the Wealth of Nations.

Yet even in both Romance and Germanic languages, where “real” and “reality” appear to be engrained, there was a time when speakers managed without these concepts. For most of the history of ancient Rome, until the late imperial period, Latin speakers had nothing equivalent to our “real”—reality was not part of their mental and cognitive apparatus. The term “real” is derived from the Latin res, i.e., thing, although the adjective realis was only coined in the fourth century. Its earliest uses in medieval Latin, whence it passed into Old French and thence into English, were to do with things and objects, as opposed to persons, and also with property, particularly of the immovable kind.

As for “reality” itself, it would be almost another millennium before that came into existence, in the form of the neologism realitas coined by the theologian Duns Scotus at the end of the thirteenth century. Even then the word didn’t mean anything like our reality—it had to do with the formal, internal possibilities of a thing (res), and only gradually during the eighteenth century did its meaning shift towards factuality and actuality, culminating in the Kantian understanding of reality as what exists exterior to and not depending on the subject. A long shift, then, can be observed in the meanings of “real” and “reality,” towards our present understanding of them as referring to what is actually, physically existing, as opposed to false or imaginary or illusionary: things that are objectively so. And if we once again return to Latin antiquity we find that res, thing, had as many intangible senses as tangible ones (cf. the respublica, the “public thing,” the Republic—an intangible concept if ever there was one, although for all that none the less “real”).

Reification (the turning of something into a res, a thing, but this formulation is tautological …), wrote anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, is a Euro-American habit: entities are turned into objects or things when they assume a given form, with given properties, and are therefore knowable as such. Common sense though this may seem, Strathern contrasts it with the Melanesian habit of generally conceiving of entities as always already relational, thereby perturbing and provincializing our sense that, whatever the differences between us, we can all agree that there is something “out there” that we may term “reality,” knowable and manipulable as such.20

It is easy for rationally-minded moderns to write off alchemy, magic, and witchcraft as premodern superstitions. Setting aside the awkward persistence of occult practices across the world despite three centuries of rationalist criticism, these practices have an important effect in the world. As we have seen, they are rational techniques that enable those who use them to act in the world, to make an uncertain place more certain. As practices which depend for their efficacy at once on secrecy and publicity, visibility and invisibility, they are strikingly similar to the financial industry. And like finance, they are simultaneously real and unreal. And just as with the occult, it is only the persistence of the dominant Euro-American process of reification that makes us resistant to such a conclusion, that makes us insist on pointing a finger at the malevolent magicians of capital markets and shouting: what you did wasn’t real—you tricked us!

For all that the value created by the development and trading of asset-backed securities or the general expansion of debt in the 2000s turned out to be illusory, it nonetheless existed. Large salaries and far larger bonuses were paid out on the back of it, and with those or with loans secured on them, houses bought, markets for various goods and services created or stimulated, and investments made. GDP grew, tax receipts rose, governments disbursed funds.

Recognizing that reality and unreality are not antonyms, but two possible states whose actualization depends on certain conditions obtaining or not obtaining, helps us in turn understand the resort to metaphors of alchemy, magic, and sorcery when talking of finance. These are not metaphors, but catachreses.

In rhetoric, catachresis stands problematically midway between literal and figurative speech. In English, table “legs” or clock “hands” or river “mouths” are all catachrestic. They are not “actually” legs, or hands, or mouths, but these words are used by extension from their primary meanings to describe phenomena for which we have no other word, and which are in some way analogous to legs, or hands, or mouths. These are not quite metaphors as in the lines “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.” We can talk of discontent or York without describing them as winter and summer. It is not so with clock hands or chair legs: we have no other words to describe these. It is hardly surprising that Derrida’s reflections on catachresis are one of the founding texts of deconstruction, or that Spivak has extended catachresis in a postcolonial direction in arguing that the key concepts of Enlightenment political philosophy (“citizenship,” “rights”) may do service in postcolonial contexts by describing new political realities offering radically different possibilities, nonetheless connected to their Euro-American namesakes. Catachreses are troubling, disruptive, both concepts and metaphors, both literal and figurative, churlishly (their Latin name is abusio) stirring up and muddying the waters of conceptual clarity, driving home the point that the world’s neat oppositions are rarely stable.

We have no better words to describe the (un)reality that is contemporary finance, so we use these catachreses instead. We know that financiers are not alchemists or magicians, but what do they do, really? How does finance create value? Why does that value, which has so many “real world” consequences, sometimes turn out to be so prone to disappearing? If finance is not the “real economy,” why does it have such an impact on the real lives of real people? We know that finance isn’t alchemy, but at the same time we do not know what it is, what else to call it. Alchemy, or other occult terms, are open to the charge that they misdescribe reality, that their conclusions are not real. Financiers apply sophisticated statistical techniques and clear logic, yet are open to the same charge. Both alchemy and finance are in other ways entirely real, as we have seen. “Finance is alchemy, which is not real, yet both finance and alchemy are real,” would be a succinct way of stating the problem.

It might be objected that after long study and patient enquiry the workings of the contemporary financial system may be grasped by sound reasoning and demystified after all. Yet despite study after study, from the ponderously erudite to the racy bestseller, purportedly showing us how this all works, or why it doesn’t, something of the mystery remains. Perhaps the profusion of books and articles suggests there is something ineffable about finance; or perhaps this appearance of ineffability is evidence that there is a technology of enchantment at work, so that even when we think we know how things work, their dazzling effect is not dimmed. It is one thing to understand a financial system, another to contemplate making one at home.

That it should exist at all, and on such a vast scale, trillions of dollars that are mere numbers on screens (when they are visible at all); that it should have collapsed, and yet six years on that it should still exist: of course we need our catachreses to describe this, and it is the value of dealing with this monstrous phenomenon in terms of alchemy and magic that makes the odd assemblage that is VWAP so compelling.

Assembling an Occult Economics

Modern finance and modern magic and witchcraft are not merely two parallel words governed by similar logics; they are intertwined. Far from being some bizarre throwback to an irrational, premodern age, magic and sorcery—and accusations of the practice thereof, often amounting to a kind of paranoia—abound today in precisely those situations where the operations of finance capital have created the greatest inequalities and the starkest contrasts between the expectations of the many and the realizations of the few.

We remain severely limited in our ability to influence unreal reality, because we have failed to understand that it is both real and unreal at the same time, and instead demand that it always be real only. We seek to delegitimize financiers by calling them out as magicians, but we fail to realize that their magic is real. More importantly, we fail to realize that we can challenge them on their own terrain, that they have no monopoly of the technology of enchantment.

What then, if we were to learn from the gold-defecating queen screaming in frustration at the unreality of her money, pleading with her forebear and namesake to lend her her long-dead alchemist? Or better still, to become ourselves alchemists and occult operators?

We could begin with a more concerted attempt than any hitherto to generate new knowledge forms: an “economics” that would be plural, allying artists, anthropologists, sociologists, activists, feminists, environmentalists, financial practitioners, and, yes, economists, remembering both that many of us wear more than one of these hats. This catachrestic economics would be mindful of the need for a political and ethical framing of its occult techniques in favor of equality, social justice, and care for strangers: not for us either sectarian world empires or the totalizing ideology of capitalist realism. It would analyze algorithms and models, their conditions of production and performativity, but it would also perform other realities, conjure up other financial systems, even as it pointed through its performances to the modalities of operation of our existing financial system. It would be equally at ease with spreadsheets, ethnographic inquiries, and theater, refusing to privilege one above the others as constituting what is really real. It would mobilize all these and other rational, magical techniques, in the knowledge that they create the world as much as they control it. This “economics” exists already, if only in shreds and patches. Our task is to assemble it.

The immediate stage is the city’s Centre for Contemporary Art, nestled against the seventeenth-century walls. The broader stage is its program of events for its year as European City of Culture.

I am sure I could learn, but for the time being its operations remain mysterious, opaque, obscure: part science, part magic.

The Muscovy or Russia Company was actually founded in the reign of Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary I, in 1555. Its royal charter gave it the monopoly of Anglo-Russian trade. As a joint-stock company whose capital was open ended (i.e., the company continued in being after each trading voyage), it was a model for other Elizabethan and Jacobean trading companies such as the Merchant Adventurers, the Levant Company, and the East India Company. See T. S. Willan, The Early History of the Russia Company (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1956).

Felix Martin, Money: The Unauthorised Biography (London: Bodley Head, 2013), 29.

Ibid., 67 and 126.

Ibid., 130.

Ibid., 246.

Ibid., 289.

George Soros, The Alchemy of Finance: Reading the Mind of the Market (New York: Wiley, 1999).

Galina Lindquist, “In Search Of The Magical Flow: Magic And Market In Contemporary Russia,” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 29 (2000): 317.

Ibid., 316.

This story is told in Donald MacKenzie’s “The Big, Bad Wolf and the Rational Market: Portfolio Insurance, the 1987 Crash and the Performativity of Economics,” Economy and Society 33 (2004): 303–334.

Donald MacKenzie and Taylor Spears, “‘A device for being able to book P&L’: the Organizational Embedding of the Gaussian Copula,” Social Studies of Science (2014): 418–440.

Alfred Gell, “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology,” in Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics, eds. J. Coote and A. Shelton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 44.

Ibid., 54. This is not to say that Gell’s theory can be applied to all forms of art as they developed in the twentieth century. His definition of art embraces Trobriand canoe carvings (which were not, to Trobrianders, “art,” since this was not a meaningful category for them) and art in the modern Euro-American sense. It might not cover all of those art practices where artists attempt to minimize technical intervention, however. Gell suggests that the reason for public contempt for some forms of contemporary art is this art’s failure to present itself as the consequence of occult technical prowess.

Ibid., 49.

By the magic of Enlightenment I refer both to the negative dialectical relationship between reason and myth, as Horkheimer and Adorno long ago described it, and more generally to the very idea of “Enlightenment” as a rallying cry. The metaphor of Enlightenment, the light of reason shining in the face of darkness, superstition, atavism, and fanaticism, is itself a powerful technique. Its use allows the speaker to position him or herself as the defender of rational and civilized values, as the standard-bearer of progress, morally and politically in the right, while foreclosing any rational inquiry into the coherence of these claims. In this a-historical version, “Enlightenment” has nothing messy or contingent about it, nor does it cast a shadow.

David Graeber, “Beads and Money: Notes Towards a Theory of Wealth and Power,” American Ethnologist 23 (1996): 4–24.

Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff, “Occult Economies and the Violence of Abstraction: Notes from the South African Postcolony,” American Ethnologist 26 (1999): 279–303.

Marilyn Strathern, Property, Substance, & Effect: Anthropological Essays on Persons and Things (London: Athlone Press, 1999).