The Second Coming of What?

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.—W. H. Auden, “September 1939”

The Congress of Versailles, 1919, can be viewed as the moment when the political landscape of modernity was fully shaped as a world-scape.

In the same year, William Butler Yeats—referencing the apocalyptic postwar context—wrote “The Second Coming,” a poem about the collapse of social order and the decomposition of civilization.

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”

In the years following the immense devastation of the First World War, Yeats speaks of the painful “blood-dimmed” chaos that is unleashed upon the world, and sees a sign of the second coming of Jesus Christ.

I’m reading Yeats from the point of view of today, 2017, and I want to interpret his words in a nontheological way, one hundred years after the beginning of the Russian Revolution, which aimed to eliminate war and exploitation from the history of the world but resulted in the creation of a miserable totalitarian regime of oppression.

The second coming of communism will happen on grounds that have nothing to do with Leninist force and Bolshevik coercion, nothing to do with political dictatorship. The second coming of communism will happen as an effect of the trauma that capitalism (and the capitalist use of technology) has inflicted on the human mind. Economic competition and obsessive accumulation have provoked violence, frustration, and war. Communism means ridding ourselves of the superstition of property and the superstition of salaried work. The redistribution of wealth and the emancipation of social time from the blackmail of salaried work: there is no other key to the future.

What happened in 2016 (Brexit, the victory of Trump, spreading nationalism in Europe, spreading civil war around the global) is jeopardizing the mental world-map inherited from the modern age. This is confirmed by an article entitled “Toward a Global Realignment” by Zbigniew Brzezinski, published in The American Interest in June 2016.1 Until his death in May of this year, Brzezinski was a leading foreign policy intellectual who for decades was an authoritative representative of the American establishment. According to Brzezinski, Daesh is only the beginning of a terrorist planetary war that will mark the current century. Westerners, Brzezinski says, have to realize that after five hundred years of predation, massacre, and humiliation, the colonized peoples of the world have started taking their revenge, launching religious and national wars everywhere. The oppressed of the world are able to take revenge now because of the accessibility of deadly and massively destructive weapons. After centuries of plunder and humiliation, the victims are reacting. On the other side, white Western workers, impoverished by the financial aggression of the last thirty years, are seeking social revenge and unleashing a global racial war. From an internationalist point of view, this is the worst-case scenario—a perfect recipe for the defeat of the human race.

The victory of Donald Trump is the price that the white working class is willing to pay in order to take revenge against the neoliberal left. Humiliated people sometimes decide to identify with the humiliator in chief. Humiliated white US workers have chosen Trump because he is the humiliator of the humiliating neoliberal elite. They think: he is our man because he is the one who best knows how to humiliate those who have cheated us.

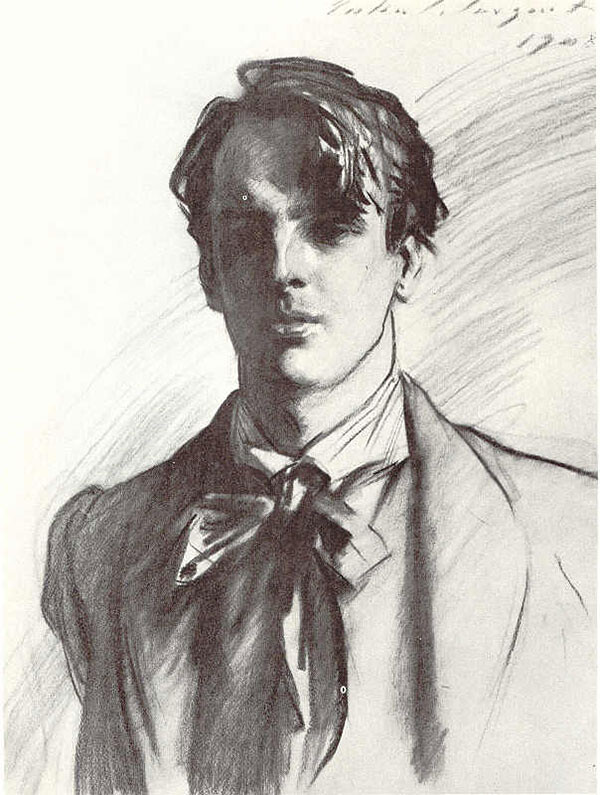

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of William Butler Yeats, 1908. Pencil, 9 x 6 in.

Unavoidable and Unpredictable

In the crystal ball of our century, it’s easy to see an increase in war and exploitation. But we should never forget that the unavoidable usually does not happen, because in history it is the unpredictable that prevails.

Our first task as intellectuals is to describe the unavoidable. We have to look straight into the eyes of the beast. But simultaneously we have to remember that the game-changing event that opens a new view and new possibilities is unpredictable. The more complex a system is, the less we can predict the wide-ranging effects of a marginal cultural trend or an unknown technical discovery.

Thus, notwithstanding our feelings of despair, we should not stop exercising the art of thinking and the art of philosophical imagination. I know that in the age of communication and speed, thought is dismissed as an old habit. Thought seems ineffective and ornamental. But this is part of the unavoidable.

We should not stop thinking because the unpredictable may soon need to be thought, and this is our job, our task: thinking in times of apocalyptic trauma.

This is why we should not stop repeating the word internationalism.

You know what internationalism is.

When Lenin wrote that “capitalism brings war like clouds bring the storm,” he knew that the First World War was unavoidable, and he knew that this unavoidability could only be subverted by the unpredictable: a workers’ revolution. In 1914, while French and German socialists voted for war credits, succumbing to the rhetoric of patriotism and accepting national war, Lenin said no to the war. I’ve never been a Leninist, but I cannot deny that at the Zimmerwald Conference in 1915, Lenin was right.

Similarly today, despite the unavoidability of war, we must say no to the war. We must organize desertion and boycotts; we must prepare the overthrow of the system that has generated the war. Internationalism is not a moral value nor an ideology, but the materialist understanding of a simple fact: the workers of the world share a common interest, which is having more of what they produce, and working less.

When workers are united in a social conflict, they can win. When they are captured by nationalist sentiment, when national fronts proliferate, war spreads and workers lose everything—no matter if they’re German or French, American or Russian. The rising nationalism of our time is an effect of the defeat that the working class has suffered; the betrayal by the neoliberal left has deprived the working class of all political defenses. The neoliberal left bears the responsibility for the defeat of workers, for the impoverishment of society, and for the humiliation that is now turning people against progressive values. Workers hate the left (and rightly so), because it is identified with financial aggression and neoliberal cosmopolitan conformism.

Tony Blair is now trying to come back. He wrote a message to the British people saying that Brexit was a mistake, and the mistake has to be mended. He will come back to help Britain behave. If I had to choose between Nigel Farage and Tony Blair, I would not choose Farage, but nor would I choose Blair. Blair and the Blairist left have destroyed all trust in democracy.

The Ceremony of Innocence

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

—W. B. Yeats, “The Second Coming”

The line “The ceremony of innocence is drowned” makes me think of what is happening every day in the Mediterranean Sea, where innocent people are drowned by wars fuelled by the West. This is free association, of course—Yeats could not have imagined the tragedy that war and migration are provoking in the Euro-Mediterranean in our postmodern times.

European consciousness is denying the meaning of what is happening. Everywhere along the Mediterranean coast, concentration camps are built with EU money. In Turkey, in Libya, in Egypt, in those countries led by fascist murderers like Al-Sisi and Erdoğan, migrants are detained, tortured, enslaved, killed in those concentration camps that Europeans do not want to host on their soil. Auschwitz is under construction all along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

In the 1940s, the majority of Europeans did not know and could not have known about Auschwitz. Now we know. Now everybody in Europe knows that concentration camps are back. Europeans prefer to externalize the horror, to pay executioners who are far from the eyes of European children. Nazism is externalized.

The Yeats poem unchains many meaningful if arbitrary associations: this is what poetry does. Meaningful arbitrariness is the gift that poetry offers to our minds. Serendipity in the process of meaning-making. Poetical ambiguousness is the vibrational condition that leads to conceptual discovery, to the imagining of other possible lands that we cannot see now. What is happening in the Euro-Mediterranean will not be overcome in political terms. Political decision is impotent. What we need is a reactivation of human empathy, which is beyond politics. It’s pre-political, or post-political, or meta-political—I don’t know. If the majority of Europeans are unable to feel empathy for the thousands who have drowned in the Mediterranean in recent years, they are dangerously sick. And they are sick because of the long-lasting impoverishment that financial capitalism has produced in their lives. In such conditions of apathy and depression and fear, the political reason of governments cannot decide. And the wave of migration and despair will not stop crashing on the shores of our cursed continent-fortress.

The Limit

“The best lack all conviction / while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

The best? Who are the best that Yeats is writing about? I think of people like Vittorio Arrigoni and Rachel Corrie, who were killed by frightened people they were trying to help. They were part of the community of cultural nomads who want to “stay human.” These cultural nomads, who sometimes come together in sudden conglomerations called “movements,” are not believers, and do not pretend to belong to any truth. They are skeptical and ironic; they don’t care about dogmas, convictions, and prejudices, so they look at reality with an ironic and tolerant gaze.

Wittgenstein says that the limits of our world are the limits of our language. Poetry is the enunciation that overcomes those limits. Poetry happens when language questions the limits of language. Poetry happens when these limits are surpassed by an excess of meaning, a meaning that limited language is unable to express. The potential richness of social knowledge and of technology is limited and perverted by the semiotic container of financial capitalism. Finance is a semiotic transformer of human activity, transforming richness into misery, inequality, and abstract accumulation. This is the limit that we are unable to surpass. It’s first of all a semiotic limit.

We don’t see the possibility that is inscribed in the present composition of labor, knowledge, and technology, because we are limited by the limits of our language, of our superstition: the superstition of salaried work. Our vision of the possible is limited by the preconception that if one wants to survive, one has to work eight hours a day. This is the limit that we have to overcome, and poetry is the place where the research for this overcoming happens.

In a 2014 interview in Computer World, Larry Page said that Google already has intelligent devices that could replace 50 percent of existing jobs. 50 percent of existing jobs could disappear tomorrow if Silicon Valley implemented its current innovations. This implies that working eight hours a day makes no sense.

We are accustomed to listening to the discourse of the powerful, which is based on the idea that everybody must work, and that full employment will eventually be guaranteed one day. This is the hypocritical discourse of all the candidates in all the elections in the world: they promise jobs. But this is impossible, because work is no longer necessary. This is the simple truth that power is unwilling to say and we are unable to see.

People are supposed to think that only if they have a job, only if they waste their life earning a salary will they survive and be able to raise their children. But when people learn that their work is no longer needed, that migrants and robots can take their jobs, they freak out. They become violent and xenophobic. They vote for a fascist who promises that the Nation will become so powerful that those who belong to the Nation will have the privilege of being salaried slaves all their lives. Those who voted Trump were thinking: “Some Mexican or some robot is going to steal my job.”

The problem is that your job is useless. Your time is no longer needed in the same way it was during the industrial age. But we are unable to see this simple truth, because we are unable to go beyond the limits of our language. A new division of labor time must urgently be developed. The goal is not to defend the existing composition of labor, but to disentangle the possibility of a new one, to emancipate the general intellect, to liberate the power of science, technology, and art from the limits of our language, from the limits of the superstition of work.

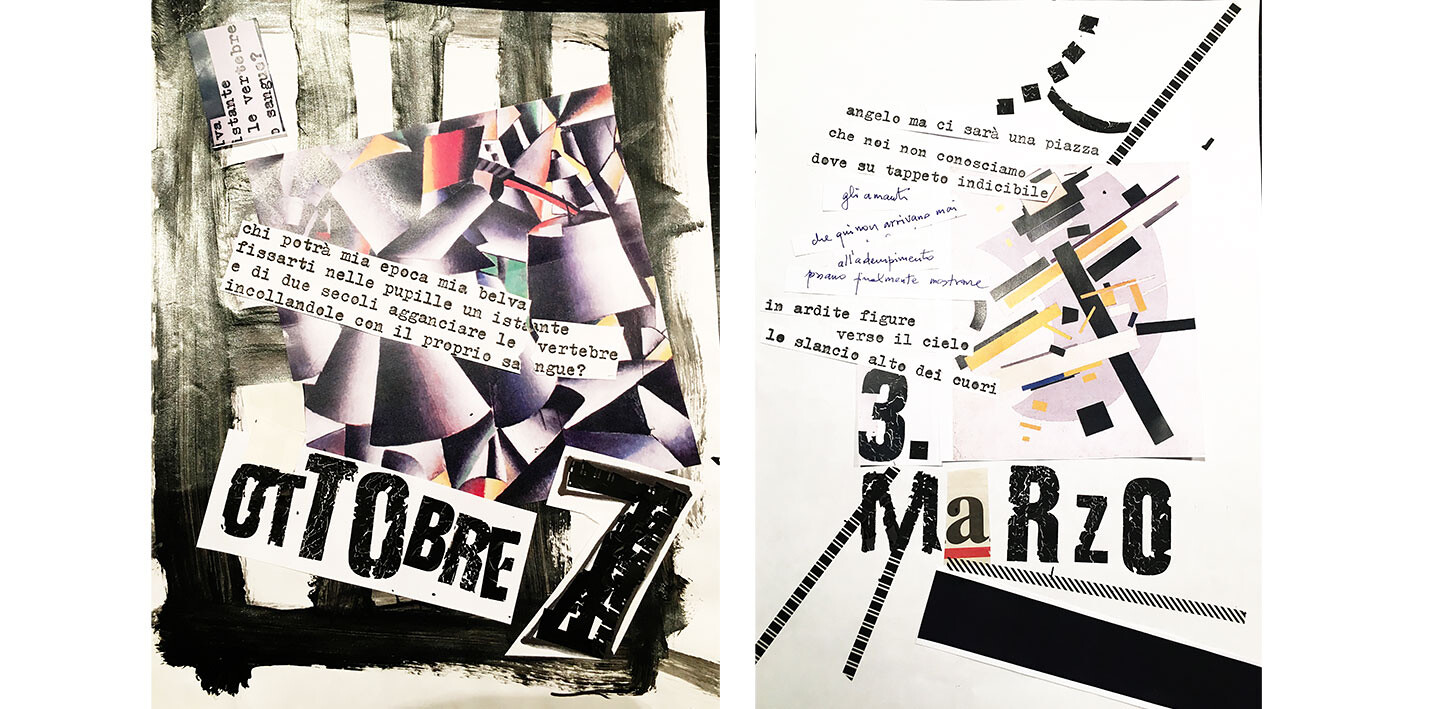

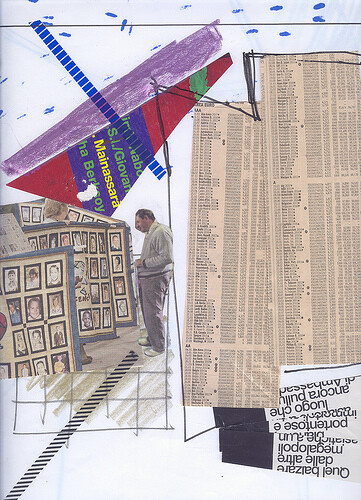

Illustration by Istubalz (Istituto di Studi Balzanici). Courtesy of the authors.

Irony and the Limit of Our Language

“The best lack all conviction,” says Yeats. Think of the former German pope, Joseph Ratzinger—Pope Benedict XVI—who came to Rome promising the final establishment of truth. Ratzinger was an intellectual and a supporter of absolute truth. Right-wing Catholics felt emboldened by his ascent to the throne. He said: “God is one, and the Truth is one.” In his best-known speech, delivered in Regensburg, Bavaria, the philosopher Ratzinger denounced relativism, which he regarded as the plague of modernity.

I’m not generally a fan of Nanni Moretti, but I like Habemus Papam, the movie he directed in 2011. It’s a movie about the fragility of human beings—in particular, about the fragility of a human being who is elected pope. In the movie, Cardinal Melville (played by Michel Piccoli) is elected pope. When he is expected to give his first public speech to a massive crowd assembled in St. Peter’s Square, he realizes that he has nothing to say. All of a sudden, he is overwhelmed by the reality of the world, and he mumbles: “I cannot speak.” Then he goes to a psychoanalyst (played by Nanni Moretti himself). The pope is depressed because he has seen the truth that he was trying to conceal: there is no truth in the world.

In February 2013, Joseph Ratzinger decided to follow in the footsteps of Michel Piccoli. Ratzinger became the first pope to resign in five centuries.

Today, the relationship between reality and imagination is growing more complicated than Jean Baudrillard could ever have imagined. The real pope imitates the actor impersonating the pope, and accepts the dark truth that he is not strong enough to sustain the responsibility of telling the truth because he feels that the truth is evading him.

Obviously, this is only my interpretation of the resignation of Ratzinger, which was an act of intellectual courage and moral humility. How does one understand the decision of a pope, who has been chosen by God through the intermediary of the Holy Spirit, to resign? I think the only possible interpretation is that Benedict felt depressed, and spoke sincerely with God, and humbly revealed his intimate apocalypse.

Depression is not about guilt, nor is it a limitation of the reasoning mind. It is the disconnection of reasoning from desire.

Then Mario Bergoglio was elected pope, becoming the first Pope Francis in the history of the Catholic Church. He went to the window overlooking St. Peter’s Square and said: “Buonasera. I’m the man who comes from the end of the world.” He meant Argentina, a country ravaged by the beast of financial capitalism. Since that moment, the apocalypse has shone through the acts of Bergoglio, because he is a man who dares to face the end. From the end of the world, Francis has been opening a new path in theology.

Shortly after his election, he gave an interview to the magazine Civiltà cattolica. In the interview, he reflects on the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. My interpretation of Bergoglio’s remarks is that the main problem for Christians today is not faith. Nor is it truth. Something is more urgent: the focus of Christians today should be charity, mercy, the living existence of Jesus. The Church, in the words of Bergoglio, should be thought of as a war hospital.

It is sometimes called “compassion.” It is sometimes called “solidarity.” Deleuze and Guattari, in the introduction to What is philosophy?, speak of “friendship.” What is friendship? It is the ability to create a common world, a world of ironic enunciations and expectations. Friendship is the possibility of creating a common path in the course of time. As the Zapatistas say, quoting the poet Antonio Machado, “Caminante no hay camino el camino se hace al andar.” We make the road by walking. There is no truth, there is no meaning, but we can create a bridge beyond the abyss of the nonexistence of truth. “The best lack all conviction” means that the best have irony, the nonassertive language that aims to tune in to many levels of meaning. The ironic smile also implies empathy, the ability to share the precariousness of life without heaviness. When irony is divorced from empathy, when it loses the lightness and pleasure of precariousness, it turns into cynicism. When irony is divorced from empathy and solidarity, depression takes ahold of the soul.

For semiologists, cynicism and irony are related, because they share the presumption that truth does not exist. But we have to go beyond semiology: the two concepts differ because the ironic person is someone who does not believe but rather feels empathically the common ground of understanding. The cynical person is someone who has lost contact with pleasure and who bends to power because power is his only refuge. The cynical person bends to the power of reality, while the ironic person knows that reality is a projection of the mind, of many interwoven minds.

When philosophers realized that God was dead and there was no metaphysical foundation for our interpretations, different ethical stances emerged. One stance was based on aggressiveness and the violent enforcement of the Wille zur Macht: there is no truth in the world, but I’m stronger than you, and my strength is the source of my power which establishes truth. Another stance was irony: friendship and egalitarian sharing can build a bridge of meaning across the abyssal nonexistence of meaning.

Biorhythm and Algorithm

Depression can evolve in different ways: if you look at the present reality of America, you see that the prevailing evolution of depression is Donald Trump.

“The worst are full of passionate intensity,” says Yeats. Faith in belonging and identity is the fake ground of passionate intensity. Belonging implies a natural ontological or historical ground of conformity among individuals. This is why belonging implies violence and submission. If you want to belong, you have to accept the rules of conformity. Identity is the result of this process of conformity and subjection. Passionate intensity is the foundation of the identity that humiliated people crave. But identity has to be protected against existence, against transformation, against becoming, against pleasure, because pleasure is dis-identity. Identity is a simulation of belonging that is asserted through violence against the other.

“Surely the second coming is at hand. / … a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi / Troubles my sight.”

In 1919, Yeats expected the second coming of Jesus Christ. However, in the decade that followed, Jesus Christ did not come back. Hitler came.

So we should ask: What is going to happen now?

I’ll try to reframe the present situation from the point of view of rhythm. In particular, I want to say something about algorithm and biorhythm.

Rhythm is the singularization of time. Rhythm is scanning time in attunement with cosmic breathing. Rhythm is the vibration that aims to harmonize the singularity of breathing and the surrounding chaos. Poetry is the error that leads to new continents of meaning.

Although the theory of biorhythm elaborated by Wilhelm Fliess at the end of the nineteenth century is generally considered pseudoscientific, I’m interested in its metaphorical implications. The organism is composed of vibrant matter, and the pulsations of the organism enter into a rhythmic relationship with the pulsations of other surrounding organisms. The conjunction of conscious and sensitive organisms is a vibrating relationship: individual organisms search for a common rhythm, a common emotional ground of understanding, and this search is a sort of oscillation that results in a possible (or impossible) syntony.

Within the conjunctive sphere of biorhythm, the process of signification and interpretation is a vibrational process. When the process of signification is penetrated by connective machines, it is reformatted. It mutates in a way that implies a reduction: a reduction to the syntactic logic of the algorithm.

The word “algorithm” comes from the name of the Arabic mathematician Al-Khwarizmi (meaning, a native of Khwarazm), whose work introduced sophisticated mathematics to the West. However, I prefer a different etymology and a different meaning. “Algorithm” for me has to do with the Greek word algos, meaning pain. Furthermore, the English word “algid” refers to frigidity, both physical and emotional. So I suggest that “algorithm” has to do with frigidity and pain. This pain results from the constriction of the organism, the stiffening of the vibrational agent of enunciation, and the reduction of the continuum of experience to the dictates of computation. When the social concatenation is mediated by connective machines, human agency undergoes a process of reformatting.

No one really knows what human agency is, or what humans are doing when they are said to perform as agents. In the face of every analysis, human agency remains something of a mystery. If we don’t know just how it is that human agency operates, how can we be so sure that the processes through which nonhumans make their mark are qualitatively different? An assemblage owes its agentic capacity to the vitality of the materialities that constitute it. Something like this congregational agency is called shi in Chinese tradition. Shi helps to illuminate something that is usually difficult to capture in discourse: namely the kind of potential that originates not in human initiative but instead results from the very disposition of things. Shi is the style, energy propensity, trajectory, or élan inherent to a specific arrangement of things. Originally a word used in military strategy, shi emerged in the description of a good general who must be able to read and then ride the shi of a configuration of moods, winds, historical trends, and armaments: shi names the dynamic force emanating from a spatio-temporal configuration rather than from any particular element within it … The shi of an assemblage is vibratory.2

When the algorithm enters the realm of social concatenation, modes of interaction undergo a reformatting process, and algorithmic logic pervades and subjugates the vibrant concatenation. The insertion of the algorithm into the semiotic process breaks the continuum of semiosis and life. In the connective domain, interpretation is reduced to the syntactical recognition of discreet states. The vibrational sign is stiffened, to the point of losing the ability to decode and to interpret ambiguousness and irony. Difference is then interpreted according to the rules of repetition, and the indetermination that makes poetical misunderstanding (or hyper-understanding) possible is cancelled. As the semiosphere is reformatted according to the algorithm, the vibratory nature of biorhythm is suffocated. Breathing is banished from the semiotic exchange, and poetry—the error that leads to the discovery of new continents of meaning, the excess that contains new imaginings and new possibilities—is frozen. This is what Guattari called a chaosmic spasm.

The Gestalt Tangle and Chaos

In nonphilosophical parlance, what I’m speaking about here is our present impotence. Our cognitive activity is captured within the connective syntax, and the general intellect, separated by the social body, is expanding and producing according to the logic inscribed in the algorithm. The collaboration of millions of cognitive workers worldwide is entangled in the algorithmic form of capitalism: knowledge and technology are directed and contained by the dominant paradigm, the gestalt.

A gestalt is not merely a form; it is a form that generates forms according to the gestalt itself. A particular gestalt gives us the possibility of seeing a certain shape in the surrounding flow of visual impulses. But by the same token, this gestalt forbids us from seeing something else in the same flow of visual impulses. A gestalt is a facilitator of vision, and simultaneously a disabler of vision (and generally of perception). Our present political problem can be described in terms of a gestalt of entanglement and disentanglement. How can biorhythm disentangle itself from the algorithm and eventually reprogram the algorithm itself?

In “From Chaos and to the Brain,” the last chapter of Deleuze and Guattari’s What is Philosophy?, they speak about aging. Aging essentially means being invaded by chaos: the aging brain grows unable to elaborate the surrounding chaos.

Too fast, too fast—the infosphere around my brain is going too fast for emotional and critical elaboration.

Senescence is a defining feature of our times. People are living longer and reproducing less (with the exception of certain Muslim and African countries). The demographic decline of the white race is an explanation for the mounting wave of reactive supremacism, which is first and foremost an impotent supremacism. Trump won because of this sentiment.

Obama came to the fore proclaiming, “Yes we can.” But the Obama years were marked by impotence. This impotence has fed frustration and rage, ultimately nurturing fascism. Is there a way out of this impotent rage? How can we heal the trauma and go beyond the post-traumatic effects of the present apocalypse?

We must shift the focus of our theoretical attention from the sphere of politics to the sphere of neuroplasticity. We must create technical platforms to enable a neurological reshuffling of the general intellect.

I call this perspective the second coming of communism.

See →.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 34–35.

Category

Subject

—March–June 2017