“By state of war I mean state in the sense that physicists or chemists think about states of matter. Every state of matter is an order, and despite that order, every state of matter has some elements of other states,” writes political theorist and philosopher Jairus Grove.1 “World,” “life,” “reality,” “earth,” and “body” are the categories whose established interrelations have been unsettled by the state of war.

The Deadly Preemption

In 2022, after centuries of moulting, the Hobbesian Leviathan is covered with scales that neither the authors of medieval engravings nor the political philosophers of the seventeenth century could have envisioned. The huge and eerie shell of this monster consists of millions of screens and radars—its armor and weapons, its camouflage and tools of intimidation. Nowadays, in the current state of war, multitudes of bodies literally fear, hope, tremble, seek opportunities to move to a temporarily safer place, head to work or to a military recruitment office—in short, they vibrate—together with these screens, which fabricate both facts and emotions, like sincerity and fear. The monster also unleashes the sound of sirens that regulate the bodily rhythms of those who are trapped in the warzone: sleep, movement, the contractions of muscles, and the secretion of gastric juice out of horror. All of this constitutes just a few millimeters on this huge monster’s scaly skin.

Each movement of his limbs provokes terabytes of panic, spasms, and hundreds of deaths. This must be the creature that Manuel DeLanda, political theorist and researcher of contemporary wars, described back in the 1990s, noting the transferring of control from humans to software systems—not just digital technologies but human-machine systems operated by both men and machines.2 According to another author, Canadian philosopher Brian Massumi, contemporary regimes rely more than ever on such fusions, particularly between the procedures of representative democracy, information technologies (media), and the military sphere. Massumi claims that social tension reached its boiling point after the September 11th attacks—the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan carried out by al-Qaeda members.3

The Antichrist sits on Leviathan. An illustration from Liber Floridus, a medieval encyclopedia compiled by Lambert of Saint-Omer, 1120. Wikimedia Commons.

This event led the administration of the US president George W. Bush to develop measures aimed at the “preemption” of undesirable events, most of which were labelled with the well-known but incomprehensible term “terrorism.” The term is incomprehensible, explains Massumi, because it has an unstable meaning: it refers not to actual but potential phenomena and events, which have nowadays become the objects of management. Media messages, among other things, are a crucial weapon of preemption—they “visualize” the newly invented threat and provoke fear, which is a powerful political tool. They take root in the whirlpool of political and social events, in the affective states and behaviors of the population, even though they can only attest to the probable.4

The way the Russian government rationalizes its invasion of Ukraine, and more broadly, Putin’s statements about “extremism” and the threat from NATO, together prove that the doctrine of preemption has now found its way to Russia too. The preemption of constructed threats (“peacekeeping”) and preventive measures to outmaneuver other geopolitical actors determine tens of millions of actual destinies.5 Massumi wrote about “ontopower”; now it makes sense to speak of “ontowar”—the destruction of what is alive in order to prevent what is possible. How else can we understand the fact that “peacekeeping” implies the use of weapons and the targeted killing of civilians? Hiding in bomb shelters, we watch this fatal poker game, becoming “instruments” and at the same time victims of Russia’s “bluff.” But despite all the manipulations and tricks, the rules of the game involve a “kinetic” network of preemptions where every step is either an amicable gesture or a threat. It is a game that is played at the cost of thousands of lives.

This War Began in Order To Be Seen

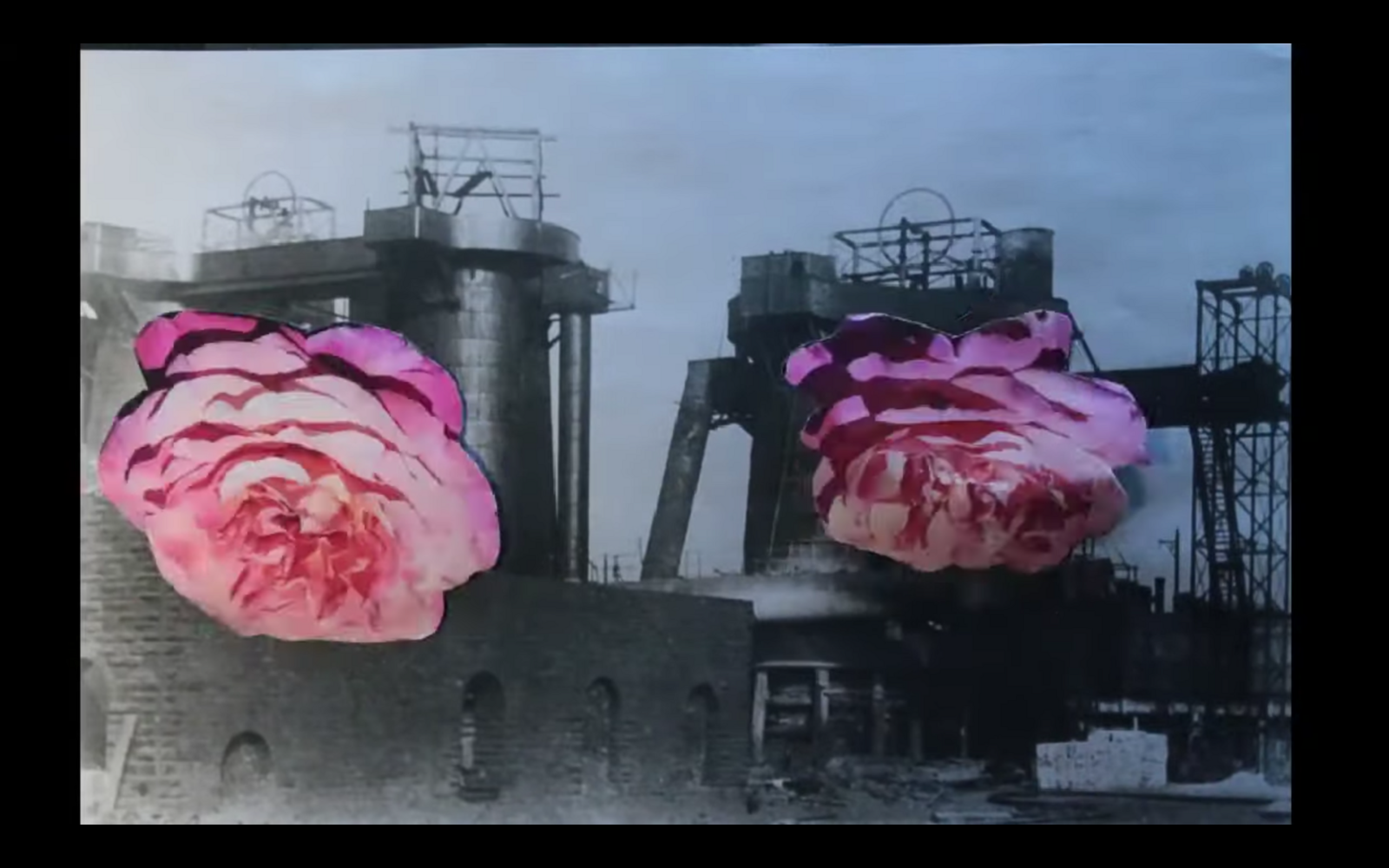

Is it possible to imagine the interplay between the real and the probable as something different than a dance of the scaly beast—the bloody “manager” of social fears and geopolitical decisions? It might be worth looking at some attempts at imagining this that come from a time before the escalation of the war in Ukraine—from the time of its origins during the hostilities in Donbas in 2014–22. One of the most remarkable attempts of this kind was watching the war (a film found online) (2018). This work was created by 443 anonymous videographers who shared their amateur mobile phone footage on social media. The footage was then edited by an anonymous film editor (or a collective). All this video documentation of the war in Eastern Ukraine was made by its immediate witnesses from 2014 to 2018. There are no television graphics, no sensational talking heads, no prophecies by experts. Only five and a quarter hours of raw video evidence of war. Some fragments of the film include intertitles with brief commentary. One of them states, “the war began in order to be seen.” Amidst the “war of preemption” that the Russian Federation legitimizes with its televised content, and the (justifiably) regulated visual regime in Ukraine, this statement is truer than ever before.

Something between AI and Nuclear

Svitlana Matviyenko, coauthor of the book Cyberwar and Revolution, recently wrote: “The war tension oscillates between two poles these seven days—AI and nuclear.”6 The internet, deepfakes, automated alert systems (sirens), and occupied nuclear power stations are the new attributes of war. Yet, just a few weeks ago, it was impossible to imagine how much could transpire between those poles: murders, artillery shelling, the siege of Mariupol, missile attacks on residential areas, nights in the metro, sirens, sirens, sirens, sirens, a friend I haven’t been able to contact for a week now, a cruise missile destroying my favorite Czechoslovakian tea set that I got from grandma along with five floors of the building, bombings of kindergartens, boarding schools, and maternity hospitals, green corridors—red rooms, sirens and bombings, sixteenth day—slept-through sirens and carried-out bombings, a fire at the biggest nuclear power station in Europe, it’s cold—where to get warm clothes?, the rape and abduction of women, uncontrolled fear for the life of your beloved, silence about those killed—out of impossibility, inadequacy, or inability to talk about it?

This is exactly the case when testimonies are much more eloquent than any interpretation of them. They manifest why the war must be stopped and never happen again, undermining cynical media chatter about strategies and preemption.

My friend, anarchist and art scholar, who joined the Territorial Defense Forces:

Here’s how I am: night duty is a very special state of mind. Everything around me becomes a meditation. Every splash of water, every movement of the trees. You try to be on guard all the time and all your memories, thoughts, and identifications get blurred as if out of focus—there is just you, your gun, the guys, and the territory. One commander says that the most fucked-up guarding happens in autumn, when the leaves fall from the trees—it sounds as if someone is walking around you. It’s interesting to imagine that, but I wouldn’t want to experience it.

During small breaks, we warmed ourselves in the dugout and exchanged a few words. Seeing a crying child showing through the stitches of a tough masculine commander feels like having a mixer in your stomach. After this, one could space out staring at the grass really long. A sudden bus at high speed during the curfew, “ready” command, position, stock, aim. It turns out to be the bus carrying morning-shift workers. Back to smoking.

At dawn, Dima and I talked about cinema. Dima believes that cinema is inferior to literature as a means of expression because you spend much more time with a book than a film. It’s a really interesting point, something to dig into. I studied at the department of art theory & history and I never thought of it. Dima served in the military after school and worked at the factory all his life. He listens to rap, smokes pot, and tries to have fun. He is thirty-eight, his child was born last year. He likes Wong Kar-wai and is a fan of Asian cinema in general. Dima communicates by quoting Omar Khayyam, Confucius, and other awesome guys.

As it was getting dark, the cop began to talk about Maidan. My platoon commander turned out to be an ex-cop. Talks about coup d’états, power, and theft. Fishermen, factory workers, former patrolmen, pensioners, junkies, alcoholics, contract soldiers from urban villages and regional centers. It’s like interviewing people who could easily be labeled “the salt of the earth,” but then the shift ends, civilian life rapidly breaks in, and “common sense” reminds you that everything is not so clear-cut and it shouldn’t be seen as black and white. No cigarettes in shops, endless queues for free chicken from the humanitarian aid distribution points. I inhale the last puff and drift off. Soon there should be news from another city; maybe the guys can take me to a new platoon of their military unit. I wake up late in the evening, waiting for the moment when my parents fall asleep. Now I’m sitting and writing this improvised report. Life goes on and that’s beautiful.

My friend Asia Bazdyrieva, researcher and member of the Geocinema collective, in her notes about the war: “I could no longer talk, I simply howled. Not wept, but howled like an animal. There was a break between the world and reality, and I was thrown on this side.”7

A howl and a break, “a mixer in the stomach”—this is something bigger than “I,” a separate personality with its own experiences.

Autonomous Weapons and Geosomatocide

“Autonomous weapons” (unmanned tanks, cruise missiles, anti-aircraft missiles, anti-missile satellites) and cyberattacks have hardly proved to be the means of more humane wars with minimal losses. Quite the contrary: as part of the military and police formation of Putinism, they have turned civilians’ bodies into targets of “functional damage.” Artist Dana Kavelina, who made the film Letter to a Turtledove, once pointed out that bodies, first and foremost female ones, are the media for messages sent by the aggressor. Again: this “war began in order to be seen.”

Among the multiple reasons to label Putinism as fascism, one is that both are practical incarnations of drastic futurist reveries. These reveries extol technology and destruction, and evince a hatred for the body. But Putinism incorporates something that the futurists lacked: neoliberal capitalism as the condition for the corruption of the international organizations that should have guaranteed peace.

This will to annihilate allows us to highlight something that connects AI and nuclear power: the body, but not as an individual human organism, rather as a network of “my” relationships and interactions, as a tension between the individual and its environment. In this sense, a conglomeration of selves united by a common territory form a multiple body—a shared membrane where fear, pain, and hope spread from Mariupol, Kharkiv, and Kherson to Lviv and Uzhhorod, and now also to Warsaw, Krakow, Berlin, and Bucharest, and back. It is important to note that when it comes to the geopolitical decisions of both Russia and the international organizations trying to preserve peace for the sake of “humanity,” the Ukrainian bodies are not entirely human. First and foremost, we are quantitative indicators; that is, we are a human shield for Europe, and we are targets on a map for the Russian Federation, since human rights are clearly the rights of Western humans only. The Ukrainian body is at best the object of humanitarian aid, but not of ius humanitatis.8

Geo in “geopolitics” and “geography” has regained its literal meaning. In Greek, geo is the earth. Nowadays in Ukraine there is nothing more unstable than the territory, but at the same time nothing more tangible than the earth. Geosomatic community. The war in Ukraine is geosomatocide: the destruction of bodies, the devastation of the earth, and a nuclear threat hanging over Europe. Military aggression as a response to what might have happened seeps into bodies along with air and water, grows into green zones, leaves residential areas in ruins, and takes hundreds of lives daily. Recall the quote from Jairus Grove: “By state of war I mean state in the sense that physicists or chemists think about states of matter.” The perverse epistemic software of the capitalist West and of Putin’s extractivist patriarchal regime cannot register the magnitude of the losses taking place: the earth, whose abstraction is territory, and bodies, whose abstraction is population numbers.

According to perverse capitalist reason, the losses for actors and observers are totally different. Someone risks their bank account numbers, even though these numbers are so huge that it’s impossible to convert them into any tangible human value. On the other side, except for radar “threats” and arithmetic indicators, this game means scorched earth, destroyed buildings, interrupted future, and lost lives. Military processes, both actual and potential, are embedded into bodies and landscapes—as physical and chemical reactions provoked by high-tech weapons, as mass migrations of bodies around the planet, as clouds of dust that can’t settle between explosions and shellings, as mutilated bodies and fractured lives. This situation would look totally hopeless if the Global West hadn’t already faced the organized political rebellion of bodies and the earth—decolonial and ecofeminist groups, leftists against the extractivist appetites of capitalism, and cooperated movements of the displaced who are sick of being “quantified.”

Yet it is complicated to answer the question of how a whole neighboring country has become an automated weapon of mass destruction that acts not only against its own population but also against the logic of capital accumulation. This is exactly the reason to think of the old character from political theology tales—Leviathan.

Tentative Conclusions

The past sixteen days testify to something important. Back in the seventeenth century, philosopher Baruch Spinoza, in his unfinished Tractatus Politicus (1677), proposed a distinction between potestas, or power in the legal sense, and potentia multitudinis, the potency of multitudes united by a common political goal.9 Right now, potentia multitudinis, witnessed in thousands of volunteer efforts and military operations, concentrates around its most powerful weapons—solidarity and hope. As such, they can’t ensure safety, but they make it possible to keep up and even rekindle peace—one of the most fragile things in the world. And they make the digital Leviathan, with his nuclear tail, reconsider his plans.

This text was originally published by Your Art. Translated by Teta Tsybulnyk, Kyiv-based artist, ruїns collective.

Jairus Victor Grove, Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World (Duke University Press, 2019), 60.

Manuel DeLanda, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines (Zone Books, 1992), 167–71.

Brian Massumi, Ontopower: War, Powers, and the State of Perception (Duke University Press, 2015), 10.

Massumi, Ontopower, 12–15.

Massumi’s theory doesn’t offer an exhaustive explanation of current political events. But, in my opinion, it helps us understand why some political (in the widest sense) processes get a certain expression. After all, this theory of power is not limited to explaining the actions of the state apparatus, which makes it worth our attention as “the population.”

Svitlana Matvienko, “Dispatches from the Place of Imminence, Part 3,” Institute of Network Culture, March 5, 2022 →.

Ася Баздырева, “Письмо из Украины,” сигма, March 3, 2022 →.

human rights

Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Politicus, 3, 2.