Women burning headscarves in Sari, Iran. Source: social media.

This text was originally published in Persian on the Iranian feminist platform Harass Watch, on September 28, 2022. The first English translation of the text was published on the Arab ezine Jadaliyya on October 5, 2022.

This anonymously written text isn’t so old. It is probably three weeks old as we write this collective introduction on why we, a non-organized group of feminists in Iran, felt that it must travel beyond the borders of Iran, beyond the limits of the Persian language. There are texts throughout history that become pivotal for a people. “Women Reflected in Their Own History” is a cornerstone, an achievement in articulating a collective desire and a collective consciousness that secures it a place in the history of Persian writing. It is a prominent text in the history of all struggles throughout the longue durée of revolutions and movements in the region.

The text at hand resonates across multiple registers: the history of protest movements; creativity; identity; and the modes of production of historical agency. One witnesses a historical collision of videos taken by mobile phones, a phenomenon that was present at the zenith of the Arab Spring and the Iranian Green Movement, here folded back onto the history of photography yet revolving around the unfolding history of citizens’ choreographed performances in the street.

What makes this text a groundbreaking piece of intersectional feminist revolutionary writing? It is in the way the author interweaves feminine sexual drives and female sexuality—a feminine identification that stimulates and invites other women into its chain of becomings. It presents and brings forth the cultivation of nervous systems that spread out quickly, beyond the borders of Iran, back and forth, weaving mourning and celebration, militant struggle and discourse.

L, the anonymous author of the text, claims to be a resident of a little town outside Tehran. She must be between her late twenties and early forties. In an almost total absence of fair and unbiased journalism in the Islamic Republic, and due to the difficulty of translating between contexts in which the protests are moving ahead, the poetic prose and theorizations of L, her personal, sensual, and affective articulations, resonate with what other individuals have experienced.

Woman with torch. Source: social media.

For Zhina, Niloufar, Elaheh, Mahsa, Elmira, and those whose names I haven’t yet uttered.

What follows is an attempt to understand what one intuits about a gap—the gap between watching videos and photographs of the protests and being in the street.1 This is an attempt to elaborate the short circuit2 between these two arenas, those of the virtual space and the street, in this historical moment. I must stress that what I have witnessed and been inspired by might not necessarily apply to other cities. I live in a small town that differs from bigger cities or even other smaller ones in terms of the location where protests usually take place. This text is not intended to universalize this situation towards a general conclusion, but to elaborate on this particular situation and the influence it has had on me.

The protests reached my little town after breaking out in Kurdistan and Tehran. For some days I encountered videos of protests on the streets, passionate songs, photographs, and the figures of militant women, and on Wednesday eventually I found myself in a street protest. It was very strange: the first moments of being there, on the street, surrounded by the protesters whom until yesterday I had watched and admired on the screen of a phone—astonished by their courage, I had grieved and cried for them. I was looking around and was trying to synchronize the images of the street with its reality. What I saw was very similar to what I had watched before, but there was a gap between my watching self and my self on the street, and I needed a few moments to register it. The street wasn’t the bearer of horror anymore, but just an ordinary space. Everything was ordinary, even when those with batons, guns, and shock prods were attacking to disperse us. I don’t know how to describe the word “ordinary,” or what better synonym to use in its place. The distance between myself and those images that I was desiring had decreased. I was that image, I was coming to my senses and realizing that I am in a ring of women burning headscarves, as if I had always been doing that before. I was coming to my senses and realizing I was being beaten a few moments ago.

Being beaten in reality is much more ordinary than what I had seen before. The pain wasn’t like what I had imagined from watching the videos. While being beaten, the body is warm, as the [Persian] saying goes, and pain is not felt as expected. We had watched bodies struck by pellet bullets several times before, but those who have experienced it say pellets are not that painful or scary either. On the street, you suddenly think you must run, and the next moment you see that you’ve already started running. You tell yourself you must light a cigarette, and you see yourself there among the people and you are smoking.3 The body moves ahead of cognition and doesn’t synchronize. I think even death isn’t that scary for one who has experienced the street. The experience of the street suspends death and that’s the real fear. This is exactly what scares the viewers: watching people who are ready to die. We are ready to die. No, we aren’t even ready. We are freed from thinking about death. We have left death behind. Proximity and encountering fears and overcoming them while your body is warm: the realm of the real.

When I got away from the scuffle with the anti-riot forces and escaped into the crowd, I heard lots of cheers. After the protests, walking back home late at night, every now and then a delivery guy would pass by and show me the victory sign, or would shout, “Bravo!” I was still elated and couldn’t register the cheers and the bravos. The next day, when I saw the bruises in the mirror, suddenly the details of the struggle appeared to me. As if I had remembered a dream that up to that point I wasn’t aware of having experienced. I was reminded of the details, one by one, for the first time. My body had cooled down and my mind had started working. I wasn’t only beaten, I had also resisted and had punched and kicked too. My body had unconsciously executed what I had watched the other protesters do. I remembered the surprised faces of the anti-riot police who had me in their hands. Only after this momentary interval did my memory reach my body.

The tangible difference between the protests I had experienced in the past and the current ones is the shift from an inclination to mass and move in crowds towards a tendency to create situations. The group of protesters, right before the arrival of the anti-riot forces, would gather to create something around a situation, and would disperse with the arrival of the anti-riot police after a short struggle, according to the parameters of the street and the neighborhood, and then take shape in another spot. These situations were created by blocking the street, setting dumpsters on fire, and making a traffic jam. In this short time, the small yet active group would quickly attempt to create a situation: “Now let’s burn our headscarves.” A woman would jump on top of a dumpster, raise her fist towards the cars, and hold that figure for a few seconds. Another woman would get on top of a car and wave her head scarf. A few middle-aged women accompanied the core protesters from the beginning to the end, and as soon as the police would try to carry the protesters away, they would rush to free them. Everyone wanted to join the flood of images that they had watched in the videos of the protests the days before. Rarely would one hear any slogans and the chanters wouldn’t exceed more than a handful. The desire to become that image, the image of resistance that the people of my town had witnessed, was clear to me. Now I want to answer the question of why this is a feminist revolution and elaborate on this desire.

As I mentioned already, the current uprisings do not revolve around masses but around situations, not around slogans, but around figures. Anyone—truly anyone—as we witnessed these days, can create an unbelievably radical situation of resistance on her own, so that watching it will leave one astonished. The faith in such capacity has spread widely and quickly. Everyone knows that with that figure of resistance, one creates an unforgettable situation. People, and especially women—these obstinate pursuers of their desires—are chasing this new desire fervently day by day. This desire in turn drives a chain of desires for creating new situations and new figures of resistance: “I want to be that woman with that figure of resistance, the one I saw the picture of, and I create a figure.” These unrehearsed figures were in the unconscious of the protestors, as if they had been rehearsing them for years. This figure of resistance, this body recorded in photographs, stimulates the desire for other women to create a figure, in the next link of the chain. What desires were released from the prison of our bodies during these days!

I want to contrast the force vector that during the 2009 Green Movement, for instance, was constituted by the masses with these stimulation nodes—dispersed and diverse nodes on the street. The stimulation points, similar to female orgasm, aren’t determined and concentrated in any point of the street/body. Besides the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” and the feminist activists’ call to the first demonstrations being the starting point of the protests, I would say it’s precisely these figurative stimulation points of the protesting bodies that has made this uprising a feminist one, extending it in a feminist and feminine form and arousing women’s desires all around the globe.

Turning into those figures is one of the most apparent desires of the protesters. It’s no longer possible to go on the street without taking the figure of one of those insurgent, disobedient, militant bodies: whether on top of a dumpster, or burning a headscarf, or freeing a detained person, or just engaging in a stubborn face-off with the anti-riot forces.

The images that we’ve seen of other women’s resistance have given us a new understanding of our bodies. I think the singularity of this feminine resistance and its figural nature enabled the iconization of the screenshots and photographs, in contrast to the videos. Proud photographs reproduced and circulated en masse were immediately inscribed in our collective memory, so much so that one could draft a chronological account of this uprising based on the publishing date of these pictures. The images that aroused this uprising and carried it forward: the picture of Zhina on the hospital bed, the picture of her relatives embracing each other at the hospital, the picture of the Kurdish women in the Aychi cemetery waving their headscarves. What do we want to see from all those events? That moment, that frozen moment when the scarves are flying high, whirling in the sky. The photo of Zhina’s gravestone, the figure of the woman with the torch in Keshavarz Boulevard, the solo figure of the woman facing the water cannon truck in Valiasr Square, the figure of the sitting woman, the figure of the standing woman, the figure of the woman with a placard in Tabriz standing face to face with the anti-riot forces, the figure of the woman tying up her hair, the photo of the ring of dancers around the fire in Bandar Abbas, and several other figures.

Zhina Amini’s tombstone in Saqqez, Kurdistan. The engraving reads: “Dear Jina, you haven’t died, your name has become a code.” Source: Journalist Elaheh Mohammadi, imprisoned for covering Zhina’s funeral.

Mahsa’s relatives in the hospital. Source: Journalist Niloofar Hamedi, detained and imprisoned for publicizing and taking the first pictures of Zhina at the hospital.

Woman waving her scarf, Tehran. Source: social media.

Woman facing the water cannon on Valiasr Square in Tehran. Source: social media.

Woman tying up her hair. Source: social media.

Kurdish women in Aychi Cemetery, Kurdistan, waving their headscarves. Source: social media.

Women burning their headscarves in Saveh. Source: social media.

Woman without headscarf going face to face with the police in Tehran. Source: social media.

What permeates a photo with such a tremendously more stimulating force than a video? The time that is encapsulated in the photo. The encapsulated time condenses into the photo; it carries the entire history that the body is subjugated to. The women’s uprising in Iran is a photocentric one. What extends from this feminist footprint and doesn’t allow it to get lost? After Zhina’s name, after “Woman, Life, Freedom,” while the scale of repression is such that gathering is no longer possible and protests are not reliant on slogans, it’s the figures of women’s struggles that turn this uprising into a still-feminine uprising. This encapsulated time problematizes the linear historical narrative and highlights instead the topology of the situation: the gestures, the moments, that same incremental everyday fight we are occupied with. #for4 that moment and all those moments. Not for a totalizing narrative, but for any small thing. For those incremental moments that slip away, for reclaiming them, for that lump in the throat, for that fear, for that fervor, for that word, for that moment that has extended until now, that has dragged itself until today, under our skin, under our nails, camouflaging inside the lump in our throat. The present perfect tense, the photo’s time is in the present perfect tense: it arouses desires, brings the past into life, extends it to a moment before now and, in the now, hands over this marathon of moments to the moment, to the photo, and to the next figure.

In truth, what makes this uprising a feminist one, and differentiates it from the others, is its figural essence: the possibility for creating images that are neither necessarily representative of the severity of the conflict and the brutality of the repression, nor of the course of an event. A possibility that carries the history of bodies: a pause, a syncope, “Look at this body!,” “Watch this history all the way through!,” “Here.” The figure of the woman holding the torch, something that is self-sufficient and carries history in isolation, without reference to the moment before or after. Rather than the linear temporal continuum of video, expressing and representing the situation of confrontation, action, or repression, the history of this body is crystallized in a moment, in a revolutionary moment. Pausing on the moment when the woman is raising the torch and making a victory sign. The movement of the eyes across the frame, the shimmering light of the car behind, the raised arms, the profile of the man standing by, the trees on the street, the figure, pause. There is no need for the moment after or before in the video, because the figure is created in a historical syncope, in a pause, rather than a chronological continuum. Where the heart of history stops for a moment.

These moments and these figures are self-sufficient for representing the history of the repression of women’s bodies. And this is the idiosyncrasy that sets this uprising apart. The feminist uprising of bodies and figures. The feminist essence of these protests lies in opening the space of possibility for the creation of figural images. These images-turned-icons reciprocally affect the wish to charge the space with such images. I observed this exhibitionist drive. The bodies that wanted to be “that” figure, that had seen that their bodies have the potential to become that figure and, consequently, had endangered themselves and showed up on the scene. They were seeking to create moments of resistance within a scene where the potential to situate oneself is transient.

We have seen images of militant women before, photos of the Women’s Protection Units [in Rojava]. The difference between those photos and women’s figures from recent protests is the face-centrism of the former and the facelessness of the latter. The uniqueness of the former in armor and with weaponry and the genericity of the latter in everyday attire. The close-ups of beautiful faces in resistance uniforms (the photographer’s desire) were transformed into images of figures of resistance (the subject’s desire). “I want you to see me like this”: let-down hair with clenched fists, figures of bodies standing over dumpsters and cars.

Vida Movahed waving her headscarf on top of an electric box in Enqelab Street, Tehran, in 2017. Source: social media.

These figures remind me of Vida Movahed’s figure and the other girls of Enqelab Street.5 As if Vida is the disruptive pinnacle of representing women’s struggles in Iran. The turning point away from the message-and-face-centric videos of the White Wednesdays, mostly selfies, of women who would walk down the street and record something of their circumstances and demands on video.6 Vida Movahed became the intensive figure of all those videos that preceded her of women without compulsory hijabs strolling down the street. Silent and steady. The transition point from video to photo. The transition from the narration of everyday conditions to the creation of a historical situation. The transition from a person who talks about herself and her demands to a silent and steady figure: the figure of resistance. Here, the image of the defiant woman removed itself from the temporal continuum of video, and leapt from representing everyday conditions onto the intensive platform of historical performativity. Vida Movahed, that obscure woman, was not Vida Movahed but a photo of a revolutionary figure. The figure of all women before her, and the catalyst of all women after.

The image and the figure collapse into one another in an infinite loop. Images are published and are reproduced, and they in turn stimulate the imagination of other bodies. Individuals go to the street with the bodies they want and the bodies they can be, rather than the ones they are: with their imagination. Their revolutionary act is to interpret this image. In fact, in the intersection of the image and the street, representation and reality reciprocally guide one another.

A dream/representation/interpretation of a dream can easily impose itself on the realm of the real. To transform into that image and simultaneously inspire the desire of other bodies, the chain of images: “The short circuit of the virtual space and the street.”

Next to these individual figures, we also witness collective figures: the ring where women set their scarves on fire. The dancing ring around the fire spreads from Sari to other cities. We see the propagation of collective figures without it being clear where they come from. In the early days of the protests, a video circulated of a small group of women protesting in Paveh. The video showed a small and solitary group of women approaching from the end of a street. This small group, whose gathering seems extremely perilous, is reminiscent of the demonstrations by Afghan women. That historical situation links two images, two groups. There are many images that are never born (are not taken) and many images that don’t become operational (don’t cause a protest). Many self-immolations or deaths.

How did these figures become operational (instead of being a photo that’s merely taken)? The figures were operational because they were the historical reflections of women. I think instead of the original statement “I could also be Zhina,” the image of the woman holding a torch on top of a car strongly provoked a different desire: “I want to be that figure too.” The desire to be that promissory figure. And it was that figure that could compel women’s bodies to express themselves and to polish the rust off the mirrors in front of them. Even though that desire was provoked through the channel of an image, it became a revolutionary and blossoming desire by means of the history which that body was impregnated with. This figural desire is the idiosyncrasy of this feminist uprising. The upsurge of repressed history. Giving birth to a body we’ve been carrying for years.

The figures we have seen in activist women so far, though not all of them, the ones who were accused of exhibitionism, the figures whose mediatized faces and much-publicized names obstructed the activation of their political force and circulation—the face and the name sterilize the figure from evoking other women’s desire, since they separate that figure’s condition from the common condition of women. Now this figure is relieved of the shackles of the face and has become a faceless public one, covered with a mask, obscured due to security concerns: an image from the back, without a name, anonymous. The body politic of women is spreading across every street.

From the beautiful body to an inspiring figure. From the body confined in beauty to the body freed in the figure. This is not a transformation of the self to an ideal body, but every time and in each body, it’s the creation of a new figure of struggle. While being inspired and provoked by previous figures it has observed in virtual space, the body creates new figures and, in return, inspires future figures. The chain of stimulation and inspiration. This figure has liberated women from confinement in the body and its historical subjugation, and their bodies have flourished in its wake. A body that has just discovered the possibility and the beauty of resistance: yet another maturity.

Translators’ Afterword

Why did we feel the urge to translate, and translate yet again, and proliferate the translations of L’s text? Translation is integral to “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Women, Life, Freedom). The term “revolution” acquired its insurgent connotation in its translation from the science of astronomy—the gravitational revolution of astronomical objects around large masses. However, this decentering dimension of “revolution” went astray several times throughout history when it had the capacity to decentralize humankind or egocentrism in the constellation of living beings by acknowledging the seductive forces of “you.”

“Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” is born from the statelessness of the Kurdish struggle; in essence, it undermines the phallocentric aspects of revolutionary language. It continuously decentralizes the imaginaries of the nation-state. By putting the freedom of the other at the center of its existence, it brought to light the interdependence of the struggle of subjugated peoples. We trust that by addressing our imagined allies, immediate neighbors, and faraway comrades alike we will benefit from cultivating neural networks that bridge the bodily and the mental—similar to how Arabs, Gilaks, Baluchis, and Persian speakers have socially endorsed and translated the Kurdish “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” as the emblem of their ongoing intersectional protests across Iran.

To amplify and extend L’s text, we wish to add multiple voices who responded to two questions: Why do you think this text is so significant? How does your own experience resonate with what is expressed in these lines? The answers to the first question are gathered here, and the answers to the second question are documented in an open-source document to which more people can add their personal notes. The respondents come from several small and bigger cities, in both the socioeconomic centers and peripheries of the country, as well as the Iranian diaspora living abroad.

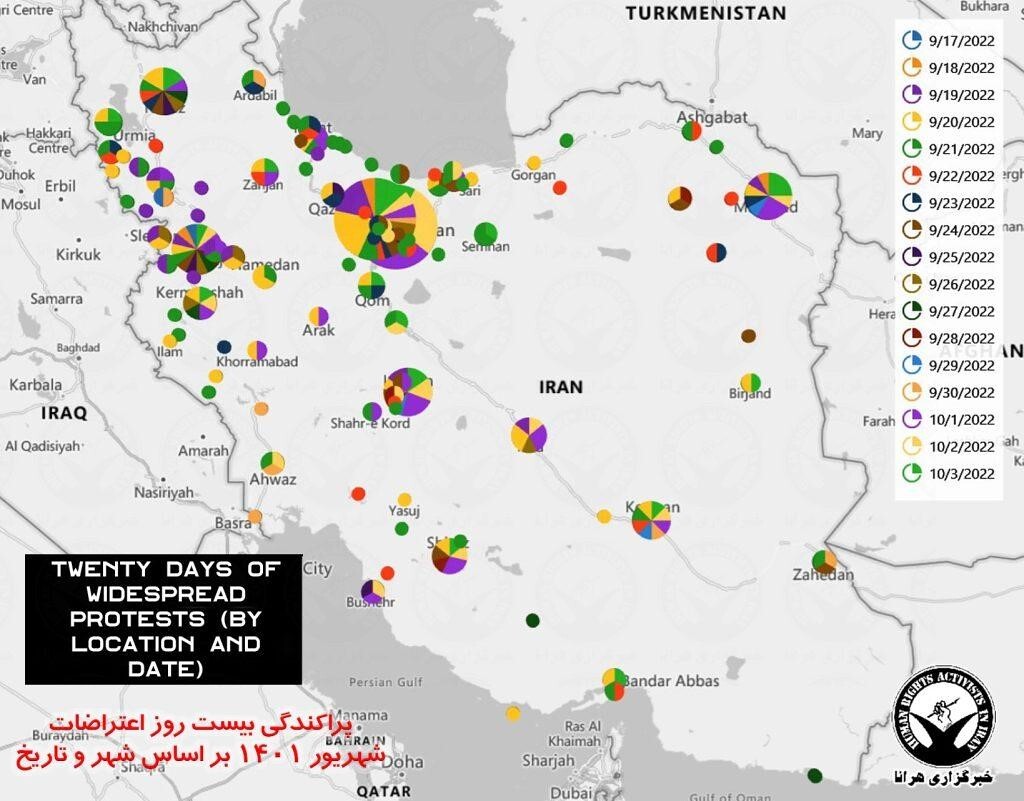

Map of 2022 protests in Iran. Source: Human Rights Activists News Agency.

One of the respondents gives an account of remembering the 2009 uprising and the struggle of a young woman with her protective father who didn’t want to allow her to join the protests. Her father, having lost a beloved to the Iran-Iraq war, was afraid of losing another. “It’s my turn,” she said. “You did your revolution, now it’s my turn!” Yet the respondent also asks how the nature of the death-driven allure of honor, which prevailed in the Iran of the early eighties, had changed in 2009, and to what extent it has changed in the recent uprisings, where swarms of high school teenage girls are on the front line, occupying the streets and their classrooms. L writes about the struggle between the fear of death, overcoming that fear, and the life-driven enunciation of bodily pleasure, the pleasure of a freed choreography of women on the street whose exhibitionism for each other stimulates other women, in Iran and beyond.

What is clear in most responses to L’s text is a sense of generational continuity for revolutionary thought. From the everyday struggle of our mothers and all the other women of our lives, towards our fresh imaginations of womxn—and, in between, long periods of faith in reformism, ongoing life, and the experience of hidden and more obvious forms of oppression—the future remains unclear, the dead ends of the past have cracked up, and we encounter the flooding anger and hope of the becoming of women. In its multiplicities, what became clear for this respondent is that “for once, we are not the minority within a minority, and we are not rebels; we are not exceptions.”

Another respondent points out the hysteric structure of the situation and how it must be difficult for those with an obsessive psychic structure to bear the unrests: there is no idea for them to hold onto without it already being coupled with the bodily and the affective, a fearful condition for obsessive minds that survive by decoupling the body, with its pleasures and pains, from words, theories, and ideas.

L’s text brings about a network of sensations and recognitions, and many of the respondents acknowledge that it evokes the very nature of the collective registration of each other, the true becoming of women reflected in their own history. For once, the experience of being “outside”—the diasporic experience—is taken out of the usual register of melancholia: the loss of one’s self to oneself, in its asphyxiating relationship to misogynistic self-resentment. The image of women’s upsurge on the street shocks the body out of its melancholic lassitude, a freedom that many of our bodies in so-called liberal settings have not yet incorporated despite years of migration. In this mirroring relationship to the image, our diasporic bodies are also freed. As one of the respondents writes:

From the start of this revolution, I’ve been grappling with “experiencing.” The experience of being freed. Like the image I’ve seen of becoming freed. I come to my senses and I realize I’m reenacting in my head, being there and ripping off and burning my scarf. It’s strange, because I’ve been freed from the hijab for years, but it’s become clear to me that the imperative of freedom hasn’t happened to me yet. I only feel the freedom from the hijab when I imagine myself in the context of being on the street, taking off the scarf from my head and being scared by staying with my fear, staying with the others. Reading this text and L’s description eased out the cognition of this feeling.

L’s text is experiential reportage, oscillating between the bodily and the mental, an expansion of the momentary gap between the body and what it translates or transfigures into the mental—and, in that very gap, calcified theories and pillars of our old language are deconstructed and restructured and, through cuts and twists and subversions, are turned into an orgasmic sensibility: a space for self-recognition, an auto-erotic moment of coming of age, the age of pride and exuberance, no matter how painful, no matter how dangerous.

The bodily experiences expressed within the text refer to identifications with the still photographs and moving images capturing the brutalities. As one respondent writes from the streets of Gohardasht, upon encountering the police her body immediately moved and stood in front of her younger cousin before she could even think. In that moment, she “could see the image of this new body reflecting back in the eyes of the people in the street witnessing what was happening.” The photographic becomes the medium of self-determination on the street. In turning bodily experience into a crossroads of seeings and showings, hearings and sensations of being beaten, gatherings and dispersals, and the retrospective recognition of the masses transmuting into more formalized crowds, the text becomes a crossroads of art history and media theory.

L enfolds the experience of watching videos back on the history of photographs, and both in relation to the choreography of the bodies who move ahead of their minds. Art history lags behind this demolished and restructured experience of performance with each other and for each other. The history of photography, of video art, and of choreography meet on the streets of a little town in Iran and they are received by the identification of women who move back and forth to distill a figural monument of themselves out of the endless hours of recorded videos, into unforgettable fleeting moments of photographs that last forever. Dispersed and unpredictable, the multiverse of such triumphs are truly described as the female orgasm, no specific spot of the street/body is there to be recognized as the center, neither for the protestors nor for the forces of repression.

Those forces are the most exhausted, the worst nightmare of anyone with a phallic fixation—performance anxiety has struck them, as is obvious in their faces and their lack of determination, and pathetically put in the cries of their social media attempts to accuse “Woman, Life, Freedom” of being the “enemy’s cultural war,” a sexual revolution. L’s love letter makes those nightmares come true, she verbalizes and analyzes the fusions of our sexual and militant life-driven dances: in our identification with each other, we become who we become.

L is ahead of language, but by breaking with the older language of disciplinary forms, by reminding us of the continuum of innovations, condensations, displacements, reformulations, and renamings, she gives language to something that is experienced collectively but turned into a collectivity named afresh. Not mothers to children, not sisters to brothers, not daughters to fathers: women, reflected in their own history. Sisterhood triangulated with the words of a refreshing, recognizable trinity: Jin, Jiyan, Azadi!

This open-source document gathers responses to L’s text. It contributes to this everyday, ongoing activity of naming, naming in the mirror of our own history. This document is an invitation to everyone to multiply these articulations by adding your own link to this “Jian”-driven chain: your experience, responses, and translations into your own language.

My lover, whom I’m watching from afar, once hinted at a letter: L. I want to let go of my usual suspicion to refer to this L in the midst of experiencing this revolutionary space, which, for me, resonates with love-making, and to claim both L and my lover’s hint. Signing this text with L is the revolutionary confiscation of their hint. While this naming shelters me from the threats of the regime’s forces, it liberates me from my notion of love, especially at a moment when names have become code names. (To “hint” in Persian is a gestural and/or implicit mode of communication, suspending the addressee in a ciphered enigmatic zone. It recalls the loaded history of the tightrope walk between iconoclasm and the insistence on wanting to watch, and wanting to be seen. The above sentences make sense when “eshareh” is understood in this way.—Trans.)

A short circuit is the irregular connection between two nodes with different voltages in an electric circuit. This causes an excessive electric current to flow through the circuit. In circuit analysis, the short circuit is a connection that forces two nodes with different potentials to level their potentials. In fact, a short circuit is a connective path between two parts of an electric circuit that can cause a current a thousand times more forceful than expected.

This sentence is from a letter I wrote to my lover when the video of the prison gates opening and prisoners being freed before the 1979 revolution went viral (see →). A letter dated August 2, 2020: “Today I watched the video of the prisoners breaking free. Again and again. Could it be me who brushes that woman’s hair away from her forehead? How to feel happiness? How slippery it is. One moment you feel something like inspiration in your heart, you think you’re happy, but as soon as you lift your eyes you see that you’re someone who once used to be happy, and now it’s more like not comprehending that fleeting moment that has made everything unintelligible. So much happiness in that video. Such an atmosphere. You don’t need to say anything, just brush away the hair from the forehead in front of you with your hands to be able to recognize her and confirm she is there. And that it is you who’s revealing her face. ‘Is that you?’ ‘Yes, it’s me.’ A face for everyone. A liberated face whose emotions are not repressed and is laughing while crying. And crying while laughing. Some kind of emotional assault. A face that doesn’t recognize the happiness and the changing circumstances yet. That moment when everything is in flux. The moment of the revolution. Not a moment before or after. A disquieting condition, the condition of becoming. How can you recognize someone in a crowd in the moment of the revolution, when all the body’s organs surpass their own intelligence and the way they’ve acquired knowledge? With brushing the hair away and searching for a bygone memory. A black mole near the right ear. Then you say you need to light a cigarette and you see yourself being there and smoking, and you say you need to go and you see yourself in the crowd. You’ve been there, already, always.” I’m sharing this private letter in a revolutionary condition: this text no longer belongs to my lover alone, but it’s for all the bodies on the street that I love wholeheartedly.

“#for” (in Persian #برای) has been a viral hashtag during the recent protests in Iran where people voice “for” which reasons they come into the streets.—Trans.

On December 27, 2017, Vida Movahed, later known as the Girl of Enghelab Street, raised her white headscarf on a stick while standing on a utility box. Pictures of her went viral. She was detained shortly after and, according to Nasrin Sotoudeh, she was released on bail later.—Trans.

Initiated in 2014 by Masih Alinejad, a prominent Iranian-American journalist and women’s activist, My Stealthy Freedom became a widespread online movement of women recording themselves on mobile cameras, protesting compulsory hijab laws. Starting as a Facebook page, already by the end of 2015 it had nearly one million likes.—Trans.