Plečnik’s Stadium, Ljubljana, 2020. Photo sportsport.ba.

What would be the most appropriate image of peace for today?

Throughout history, images of peace have most often celebrated rulers who finally brought peace after long wars. One of the earliest monuments in this sense is the Ara Pacis (13–9 BC), an alter in Rome dedicated to Emperor Augustus, who established the Pax Romana. In the fourteenth century, the progressive Republic of Siena commissioned Ambrogio Lorenzetti to paint The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, which promoted peace as a outcome of good government. The socialist authorities of Yugoslavia commissioned the construction of many partisan monuments, which communicated the idea of peace as linked above all to the victory over fascism. Peace also became one of the main symbols and values of the Non-Aligned Movement. Peace is often depicted as the result of victory over evil, good governance, and wise agreements between heads of state.

Traditional symbols of peace have become instruments of various ideologies, or else made into souvenirs and consumer goods. This is what happened to the dove carrying an olive branch, which Pablo Picasso made famous after the Second World War. In the 1960s, counterculture movements adopted Gerald Holton’s symbol of nuclear disarmament. At that time, hippies also used flowers and slogans such as “make love, not war” to communicate their anti-militarist views. Although often described as naive, these peace-loving sentiments were nevertheless produced in a strong climate of social criticism, student protests, and anti–Vietnam War demonstrations around the world.

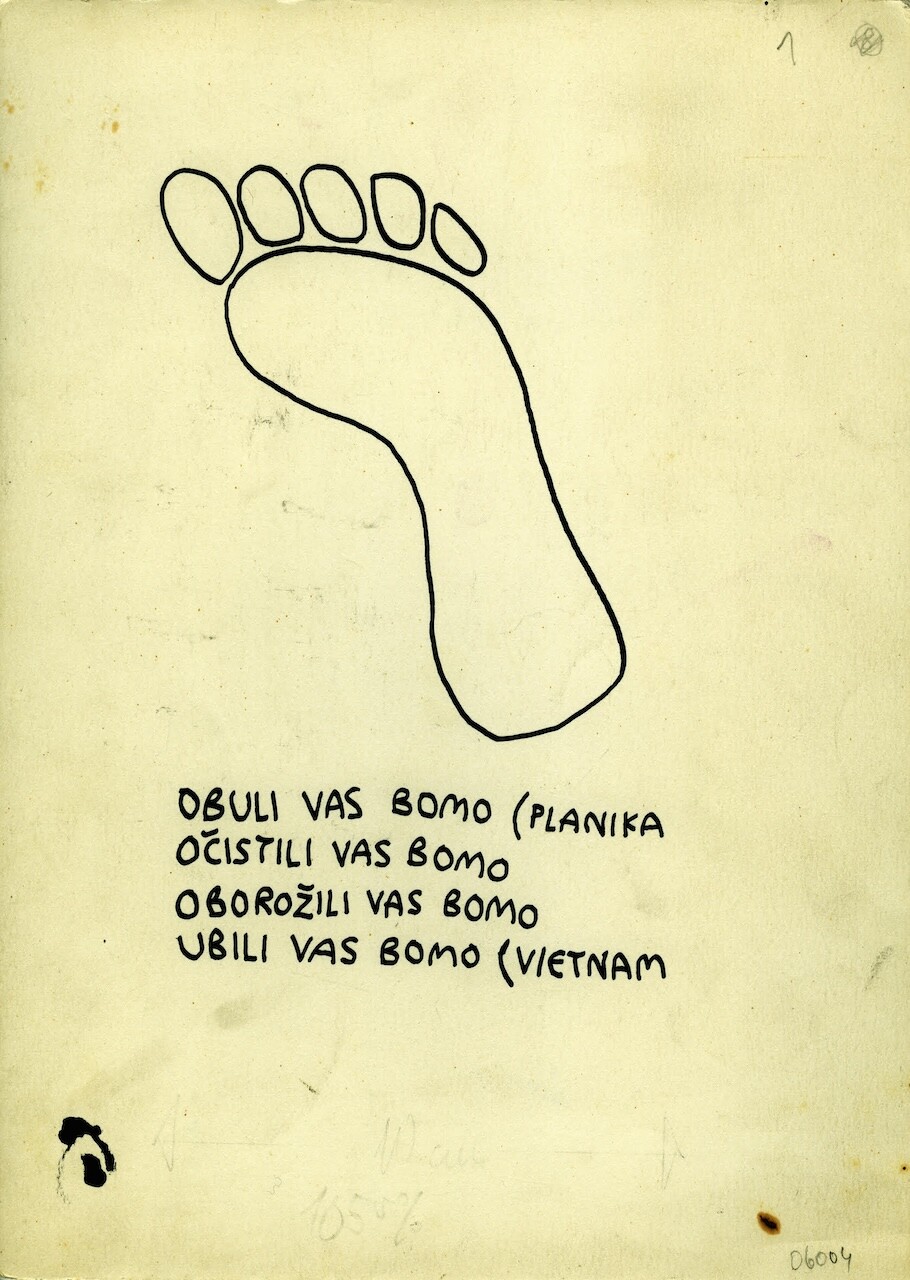

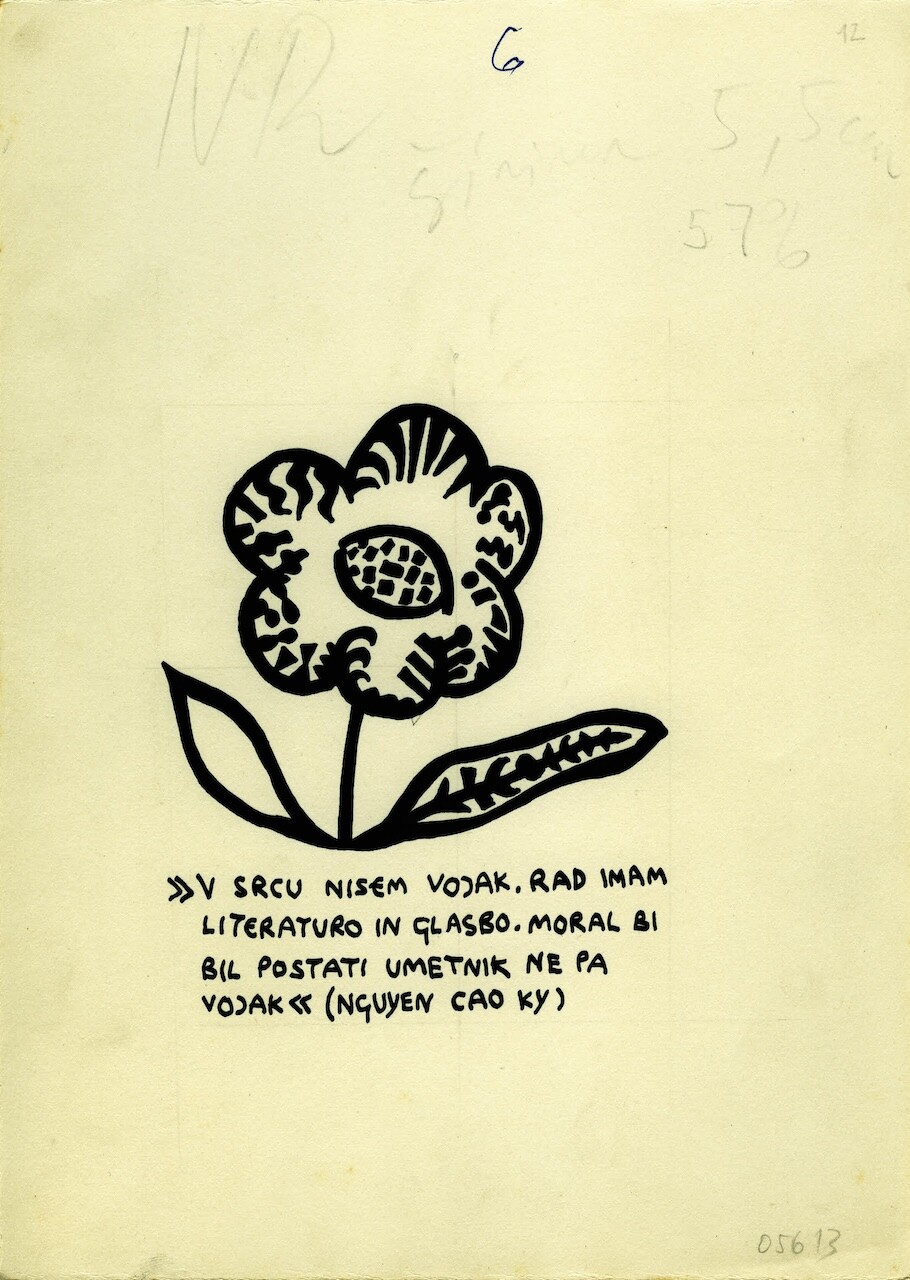

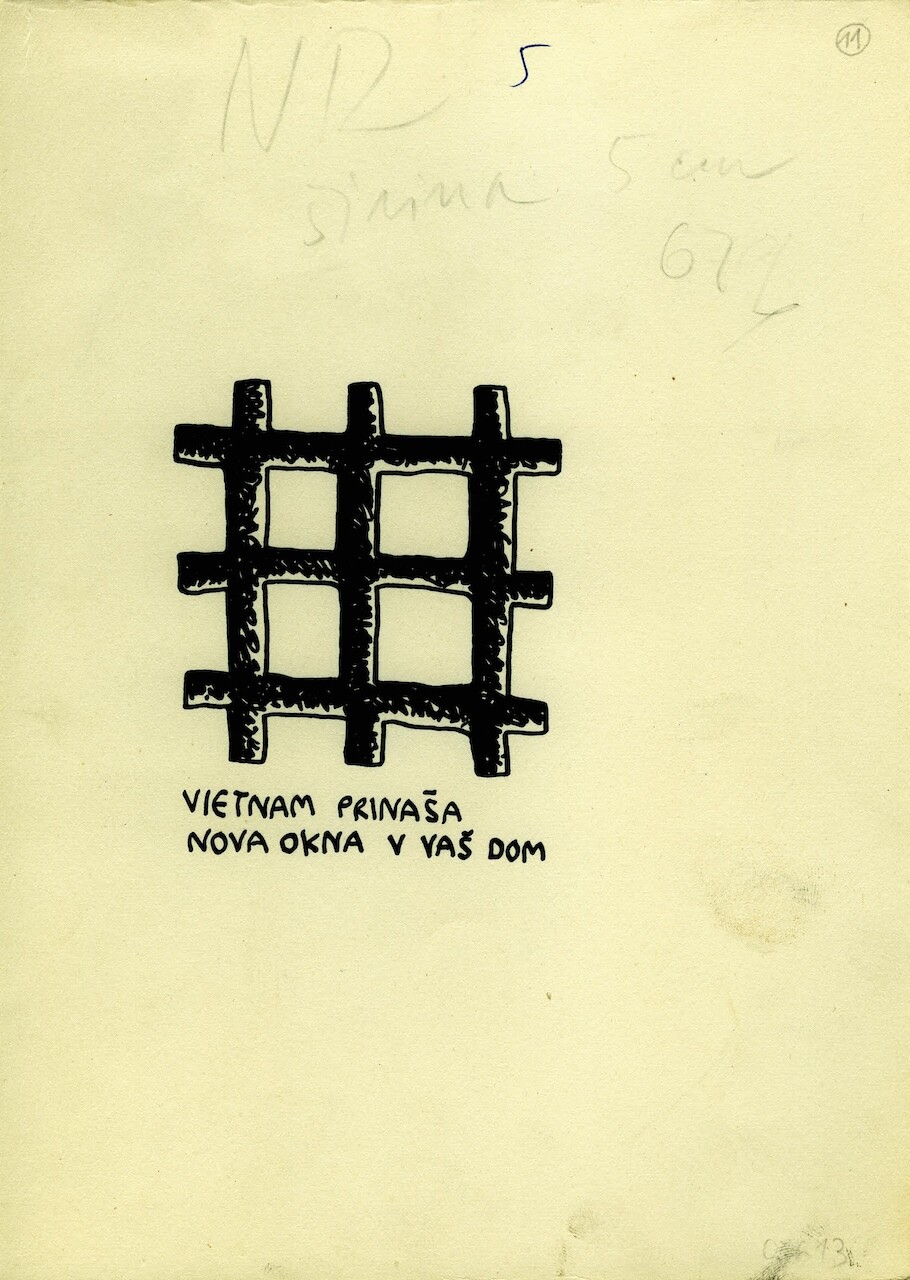

Consider, for example, the 1966 drawings of Marko Pogačnik, whose powerful message is based on witty depictions of flowers, combs, and other innocent objects combined with comments on the ease with which young boys are sent to their deaths.

Marko Pogačnik (The OHO Group), drawings published on the front page of the student newspaper Tribuna alongside a statement by the university committee against the war in Vietnam, October 26, 1966. The statement above reads: “We’ll put you on (Planika) [a Slovenian shoe factory], We will clean you, We will arm you, We will kill you (Vietnam).” Courtesy Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

“I am not a soldier at heart. I love literature and music. I should have been an artist, not a soldier. (Nguyen Cao Ky)”

Pogačnik’s drawings also allude to propaganda advertisements, conveying the message that capital was also behind the war in Vietnam—like this drawing of a grid that resembles prison bars accompanied by the phrase “Vietnam brings new windows to your home.”

With these messages, Pogačnik’s drawings are not far from the emancipatory propaganda posters of Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose satirical agitprop was aimed mainly at informing the country’s largely illiterate population about current events. One of his posters, showing a Russian and a Ukrainian soldier facing each other with their rifles pointed at a fat capitalist, could inspire us to rethink the concept of peace as victory over a common enemy. This poster, created in 1920—that is, during the Soviet-Polish War (1919–21)—reads “Ukrainians and Russians have a Common War Cry: Pan will not be the Master of the Worker!”

The concept of victory over capitalism as the common enemy of all nations was later superseded by the political doctrine of Russky Mir, which, like similar doctrines such as Pax Romana and Pax Americana, is largely linked to the cultural and political influence of superpowers. A poster from the 1980s, which visually equates the Mir space station with the Dove of Peace, is a far cry from the emancipatory character of early Soviet avant-garde posters, and shows how peace is linked to territorial expansion. It is worth noting that “mir” in Russian means “peace,” “the word,” and also “the world.” The idea of a “Russky Mir” has been taken up by Vladimir Putin and is linked to the reoccupation of Soviet territory and also to the war in Ukraine.

In political terms, peace is essentially the result of peace agreements—negotiations over the division of the world. One of the images that symbolizes peace in this sense is certainly the group portrait of the leaders of the anti-Nazi coalition—Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill—discussing the postwar world order at Yalta in February 1945. The Second World War was a war in which, as Gerard Wajcman writes in his book The Object of the Century, the “perfect crime” was invented, the crime that leaves no evidence behind, no ruins for memories to attach to. For an age that invented the “perfect destruction” that Auschwitz represents, we need to conceive of a different kind of object. Wajcman sees one such object in Malevich’s Black Square, painted in 1915, during the First World War, which would claim between fifteen and twenty-two million lives. It is a picture of emptiness, an enormous absence that is impossible to interpret. According to Wajcman, this abstract image has freed itself from reality, yet it points to the real—the real as that which can neither be represented nor articulated, but which can be touched through art.

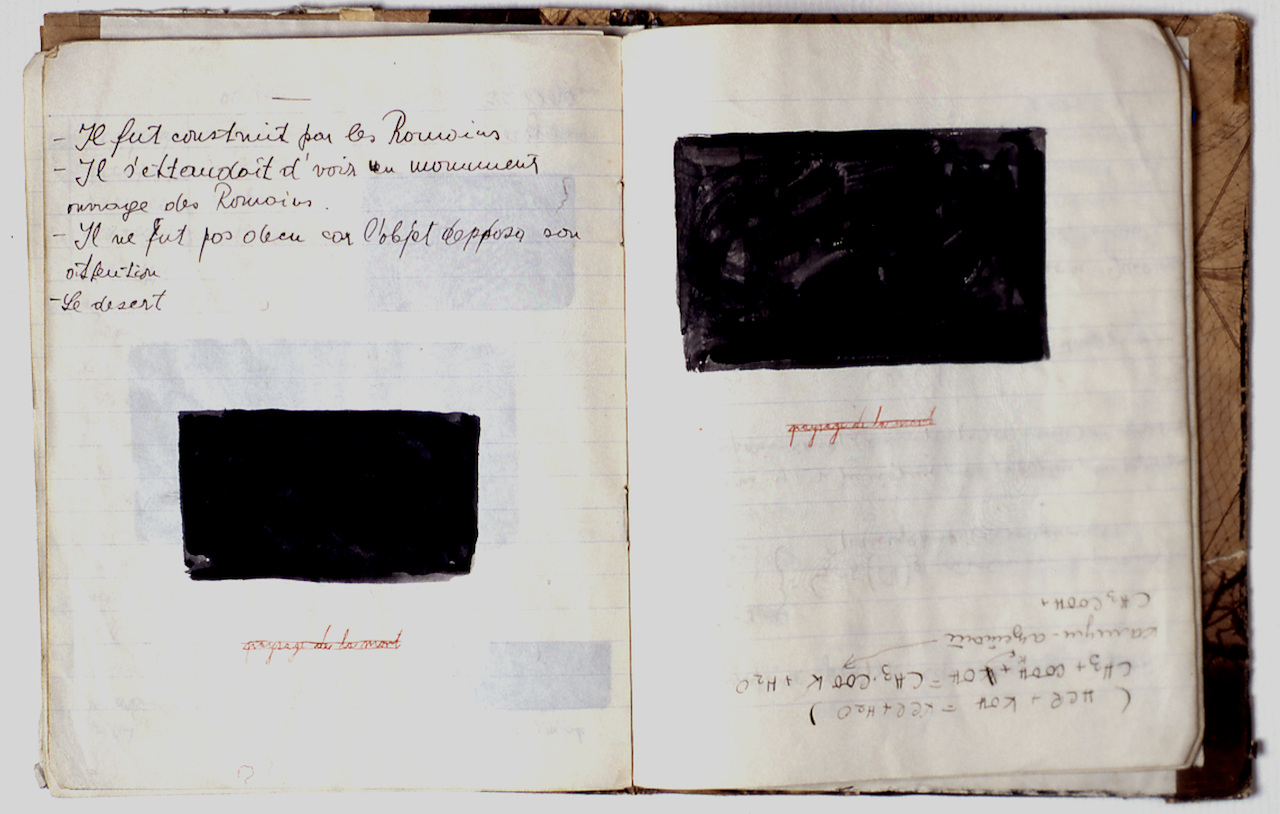

The real might also be sought in the Paysage de la mort series by Croatian artist Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos. During the Second World War, when a relative or friend of his died, Mangelos marked the death by painting strokes in his notebook, erasing what was underneath. In this way he made a kind of symbolic grave. Later, these “graves” were enlarged to a quarter page, then half, then a full page. These black surfaces, sometimes accompanied by thin red lines, letters, or inscriptions, mark the erasure of memory, which becomes a void, a nihil, like the beginning of something new. For Mangelos, this something new is above all a thought—a thought that can lead to inner peace.

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos, Fragmenti 1 0. m. 3 (1936-1942). Collection Mario Bruketa.

The idea of suffering that cannot be represented is also present in a proposal by Oskar Hansen and his Polish team for a memorial to the victims of fascism in Auschwitz-Birkenau, which they submitted to an international competition in 1958. The Hansen team’s proposal treated the entire site as a memorial. They proposed creating only an asphalt road through the camp, leaving the grass and weeds to slowly overgrow the decaying camp buildings, marking the passage of time since the tragic events. The proposal was also open to individual acts of remembrance; people could place stones related to Jewish traditions or other objects of remembrance on the road. All those affected, dead and alive, are present here and left to their own time, some in memory, others in real time.

Hansen’s proposal was, of course, too radical to be accepted, least of all by the survivors of the concentration camp. But it is certainly a concept that could also be interpreted as an image of a kind of peace that comes after annihilation, and that can no longer be the result of negotiations between people alone but also with nature, which is becoming increasingly urgent. The image of emptiness is an image of all those who are absent, but at the same time, through their very absence, those who are present. Emptiness makes absence present and thus, in a sense, creates peace between these two states.

But emptiness is not something that in itself guarantees peace; conditions must be created for the emptiness to be inhabited by hitherto uninvited agents.

Like Hansen’s proposal, emptiness is also the subject of Reflecting Absence, the national September 11 memorial at Ground Zero in New York City, created by Peter Walker and Michael Arad. Here too, the emptiness of the footprints of the Twin Towers is juxtaposed with nature—a forest of oak trees symbolizing life and rebirth. The designers intended this forest to be enjoyed by tourists as well as workers from the surrounding offices. The memorial is a kind of centerpiece of the new World Trade Center, which, according to Daniel Libeskind’s master plan, will eventually be surrounded by six towers dedicated to world trade, symbolizing the indestructible power of the American state and economy. In such a void, there is surely no room left for the other and the different.

We can only guess what aesthetic solution, if any, will commemorate those who have died in the void created by the Israeli bombardment of Gaza.

What image of peace will accompany the end of this tragedy?

Is peace even possible after genocide? In a recent interview, Lana Bastašić, a Bosnian writer living in Germany, linked her experience of the Bosnian war to the current siege of Gaza. She does not believe that peace is possible after ethnic cleansing. “Bosnia is still deeply divided. People can’t agree on what to call the language they speak. War criminals are venerated on all sides. Bosnia’s brain drain grows every year. Traumatised children have become traumatised adults, unable to find work or access decent healthcare.” Anyone in Germany today who supports the Palestinians who are suffering a fate in Gaza similar to that of the Muslims in Srebrenica is in danger, suggests Bastašić, of being branded an anti-Semite. Many cultural events featuring Palestinian artists have been cancelled or postponed in Germany since October 7. “Yet while artists and writers are cancelled for their alleged anti-Semitism, real neo-Nazism is on the rise, with the far-right party AfD, Alternative for Germany, winning local elections and mainstream politicians floating the idea of doing deals with them.”1 The far right in Germany has also usurped the dove as a symbol of peace and advocates for peace between Russia and Ukraine in the service of pro-Putin politics.

How can peace regain its value in such an atmosphere? Is it even possible to have an image that does not run the risk of becoming an instrument of manipulation?

One possible answer lies in the performative role of art, which today can serve as a space for various live encounters. And not only between people, but also between species. Like Oscar Hansen, contemporary artists are working through how to give space to wild and uncontrolled nature. The artist Jože Barši suggests that the war between public and private interests that has raged for more than a decade over the fate of Ljubljana’s Plečnik Stadium, built in the 1930s, could be resolved by a third actor. During the course of this battle, the stadium has become overgrown with grass. Barši, who sees a particular beauty in this overgrown state, proposes that the owners be allowed to build whatever they want around the stadium, as long as they leave the inside of the stadium wild and overgrown, with only minimal restoration.

There is a similar situation with one of the former barracks of the Yugoslav People’s Army, the Ljuba Šercera barracks in Ljubljana. Part of this land was earmarked for a state administration building, but no building permit was ever issued. This empty land became profitable when people started mining gravel there. The two craters created as a result of this excavation have been inhabited by a group of artists, architects, biologists, and designers who call themselves the Krater Collective. They have created their own production space, where they make paper, create objects from invasive and other wild plants, record sounds, and facilitate other interspecies encounters. Peace is not only something that puts an end to territorial wars. It is also the result of negotiations around other kinds of wars that are fundamentally connected—the invisible wars that are waged between public and private interests, between different histories, different cultures, and different ideologies.

Jože Barši, Remembering and Forgetting, 2020. Installation. Photo: Dejan Habicht.

Krater Collective (Danica Sretenović, Gaja Mežnarić Osole, Andrej Koruza, Rok Oblak, Amadeja Smrekar, Sebastjan Kovač, Primož Turnšek, Anamari Hrup, Eva Jera Hanžek, Juan José López Díez, Louisa Selleret, Edern Haushofer, Altan Jurca Avci), Feral Occupations, 2023. Photo: Amadeja Smrekar.

If there is permanent war, there should also be permanent peace, a peace that isn’t an ideal harmonious state but a state of constant negotiation that always includes those who are present in their absence. In this sense, peace doesn’t come after atrocities. It isn’t an absence of war. It is rather part of the same reality defined by permanent destruction.

What then is the most appropriate image of this kind of peace, which lives the same life as destruction?

Any image of peace can only be an image of war.

The same image can serve two completely different purposes—to manipulate, and to unmask that same manipulation. We live in an age of surveillance, which is carried out using bird’s-eye view images—not from the perspective of the dove of peace but from satellites and drones. A video by Bosnian artist Nermin Duraković shows Mount Pleševica, where the border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is located. With European Union funds, Croatia has created a void in the landscape by cutting down trees so that any migrants crossing the border will be visible from above. Duraković shot the video from a drone—i.e., with a mechanical eye—and thus provides a quasi-objective picture of reality. This image, like any image, does not mean much in itself. It is only its viewers who give it meaning: some see it as an image of a forest where they can find peace, others as a situation they have to master and control. In Duraković’s video, this image is presented as a tool of surveillance, violence, and even killing.

No image in itself can depict peace. Peace cannot be depicted. No symbol of peace has power in itself; it is an empty signifier that can be filled with contradictory content and ideologies. Peace is not a state of being. It is a process, made possible by voids in the social fabric where wild thought or wild nature can grow. Voids as symbols are only tools. For example, the Square of the Republic, a vast empty space in the middle of Ljubljana, is alternately filled by national celebrations and protests. There was a time between 2020 and 2022 when protesters on bicycles occupied the square to help overthrow the authoritarian government in Slovenia. As Lorenzetti’s fourteenth-century fresco teaches us, peace can only come from good governance, so rulers must be constantly pressured. But today things are very different than they were during the fourteenth-century Republic of Siena. Unlike the local rulers of the past, today our rulers have become more abstract and distant, so negotiations with them have to be more complex and unrelenting. Perpetual war cannot be ended by peace negotiated between parties driven by self-interest. It can only be ended by permanent negotiations open to a third interest, a planetary interest that goes beyond the interests of capital and nationalism. It may sound paradoxical, but one more nation-state needs to be created so we can move in this direction of planetary peace, and that is a Palestinian state.

Lana Bastašić, “I Grew Up in Bosnia, Amid Fear and Hatred of Muslims. Now I See Germany’s Mistakes over Gaza,” The Guardian, October 23, 2023 →.