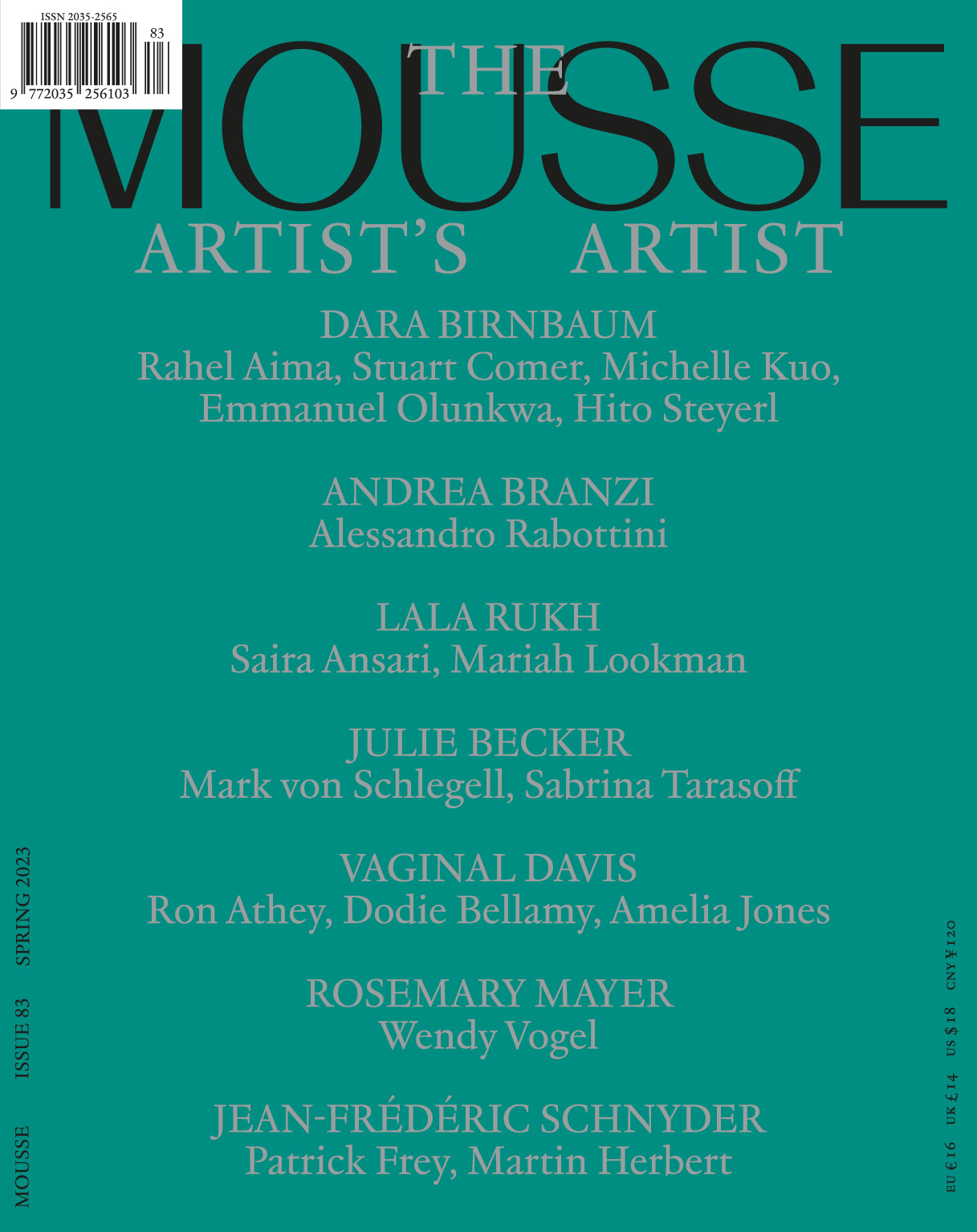

Dara Birnbaum, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (still), 1978.

We are deeply saddened by the news of Dara Birnbaum’s passing at the age of 78. In tribute to her enduring legacy, we are republishing her 1985 essay, “Talking Back to the Media”—a text that encapsulates Birnbaum’s approach to video art and media critique. First published in the exhibition catalogue for the 1985 festival of the same name in Amsterdam, the essay articulates her commitment to using television imagery to expose and subvert the ideological structures of mass media, a strategy central to her landmark works such as Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–79) and Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry (1979). As we reflect on her contributions, we honor Dara Birnbaum’s lasting impact on contemporary art and critical media discourse.

The use of television imagery began in my work with the first exhibition at Artists Space, NY, in 1977.1 That work was composed of twenty-five photographic images taken from prime-time TV and a super-8 film loop. However, it was at an exhibition at The Kitchen, NY, in 1978, that I first decided to use this "medium on itself," making a firm commitment not to translate the imagery into a different form or material. This became the approach for those works which followed (1978-1982); works which had in common the basic intentions of revealing the relationships existent within the medium of video/television and defining the industry of television as the root of video art independent of the traditional arts into this medium. In the 1980s and 1970s video has been largely developed as the extended vocabulary of painting, sculpture, and performance—completing its task through a necessary denial of the very origin and nature of video itself, TV. By the mid-seventies, I believed that by giving this medium back its institutional and historical base, new forms of artistic expression could be developed.

Much of the videowork completed from 1978-1982 attempts to slow down the "technological speed" attributed to this medium; thus "arresting" moments of tv-time for the viewer. For it is the speed at which issues are absorbed and consumed by the medium of video/television, without examination and without self-questioning, which at present still remains astonishing. Earlier works make direct reference to this "speed," as in Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978), when psychological needs are visually expressed as physical transformation — in a burst of blinding light. Or, as in the work Kojak/Wang (1980), where the needs of a young fugitive immediately trigger in Kojak a cool, non-hesitant response:

"No! No! ... Listen, I did wrong... I'll take the blame for that. Just don't ask me to give you this name..."

"I'm asking."

The earlier works are all composed of TV-fragments; structured on the reconstructed conventions of television. I see them as new "ready-mades" for the late twentieth century—composed of dislocated visuals and altered syntax; images cut from their original narrative flow and countered with additional musical texts. It was my desire that the viewer be caught in a limbo of alteration where she/he would be able to plunge headlong into the very experience of TV.

There is a cohesive effort throughout these works to establish the possibilities of manipulating a medium already known to be highly manipulative. I had wanted to establish, and set as a representative model (before the onslaught of media byproducts for the home), the ability to explore the possibilities of a two-way system of communication — a "talking back" to the media.

The growing network of video distribution in the 1970s made working with and within this medium all the more tempting; a new map with points of "access" to a public previously uncharted within our designation of "art audience." A new parameter emerged: could this new accessibility allow for a critical stance and new perspectives which challenge the dominant form?

By 1985, the growing distribution of "software," snatched with a growing industry of consumer hardware, changed the accessibility of "media imagery" for the public. In order for me to produce my first videowork, (A) Drift of Politics (comprised of TV imagery from the popular show, Laverne & Shirley, 1978), its appropriated material had to be obtained by "having friends on the inside." Source material was gathered late at night in commercial studios through friends, or through sympathetic producers of local cable-tv. Whereas in 1985, all it might take to gather "off-air" imagery, for works similar in nature, would be a simple phone call to a friend with a home video recorder (VCR). If that person is not out, running to their local video distribution store to rent yet another overnight video-movie (for as little as $1.95), they will most likely record the program for you. In addition, alternative spaces to view the "software" of the new technology were spreading in all directions—from the home arena of large-screen projection to video game arcades and new societies of rock clubs to other large-crowd "spectacles," such as baseball and other sports. In 1978 it had been nearly impossible for me to have direct access to television's imagery; in 1985 it is nearly impossible for me not to have that access.

I view my last two years of production as being initiated and carried through much in the same way as the earlier "appropriated works" of 1978-1982. The gathered footage (now from life and not television) is, as with the earlier material, subjected to minute examination — opening its composition and revealing its hidden agendas. Editing is still a highly refined process revealing the subtlest gestures—whether they be from the opening shot of a nearly-forgotten star in Hollywood Squares (Kiss The Girls: Make Them Cry, 1979), or a teenager in the streets of NYC (Damnation of Faust: Evocation, 1983). For endemic in both "characters" are the forms of restraint and near suffocation imposed through this current technological society; pressures which force a person to find the means of openly declaring, through communicated gestures, their own identity. These "looks," produced in part by mass media, require us to maintain the ability to scrutinize those projected and communicated images surrounding us. This necessity furthers itself everyday in a world which is bound by its technology — seemingly rational yet simultaneously giving rise to its irrational underside. For me, all the works completed from 1978-1985 are "altered states" causing the viewer to re-examine those "looks" which on the surface seem so banal that even the supernatural transformation of a secretary into a "wonder woman" is reduced to a burst of blinding light and a turn of the body — a child's play of rhythmical devices inserted within the morose belligerence of the fodder that is our average daily television diet.

I consider it to be our responsibility to become increasingly aware of alternative perspectives which can be achievable through our use of media—and to consciously find the ability for expression of the "individual voice"—whether it be dissension, affirmation, or neutrality (rather than a deletion of the issues and numbness, due to the constant "bombardment," which this medium can all too easily maintain). In the 1970s it seemed best to approach this task by directly appropriating imagery from the mass media — imagery which had made itself unavailable for redirected use within the public's domain while still being allowed to issue itself at the public. In the 1980s, I feel that it is a better strategy openly to re-engage the issue of possible new forms of representation, image, and meaning through our own use of the tools and by-products of the industry. We could approach these tools as possible "folk instruments," creating works which would allow new issues to surface and engaging in a practice which could reveal new "views and values"—while created through a dominant language and form.

1985

The text was written for the festival Talking Back to the Media, held in Amsterdam in November 1985 and organized by Time Based Arts, De Appel, and other local institutions as a platform for critically engaging with the mass media through artistic interventions. It was first published in the accompanying exhibition catalogue as Dara Birnbaum, “Talking Back to the Media,” in Talking Back to the Media (Amsterdam: Stichting Talking Back to the Media, 1985), 46–49.