Categories

Subjects

Artists, Authors, and Curators

Institutions

Locations

Types

Years

Sort by:

Filter

Done

222 documents

Archives of Women Artists Research and Exhibitions (AWARE)

Marie-Solanges Apollon research residency

e-flux Agenda

Posted: July 4, 2024

Category

Call for applications, Performance

Subjects

Artistic Research , Africa, Diaspora

Haile Gerima’s Sankofa, with Honey Crawford and Merawi Gerima

Haile Gerima, Honey Crawford, Merawi Gerima, Natacha Nsabimana, and African Film Institute

e-flux Events

Posted: June 27, 2024

Category

Film

Subjects

Africa, USA, Slavery, Diaspora, Blackness

Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

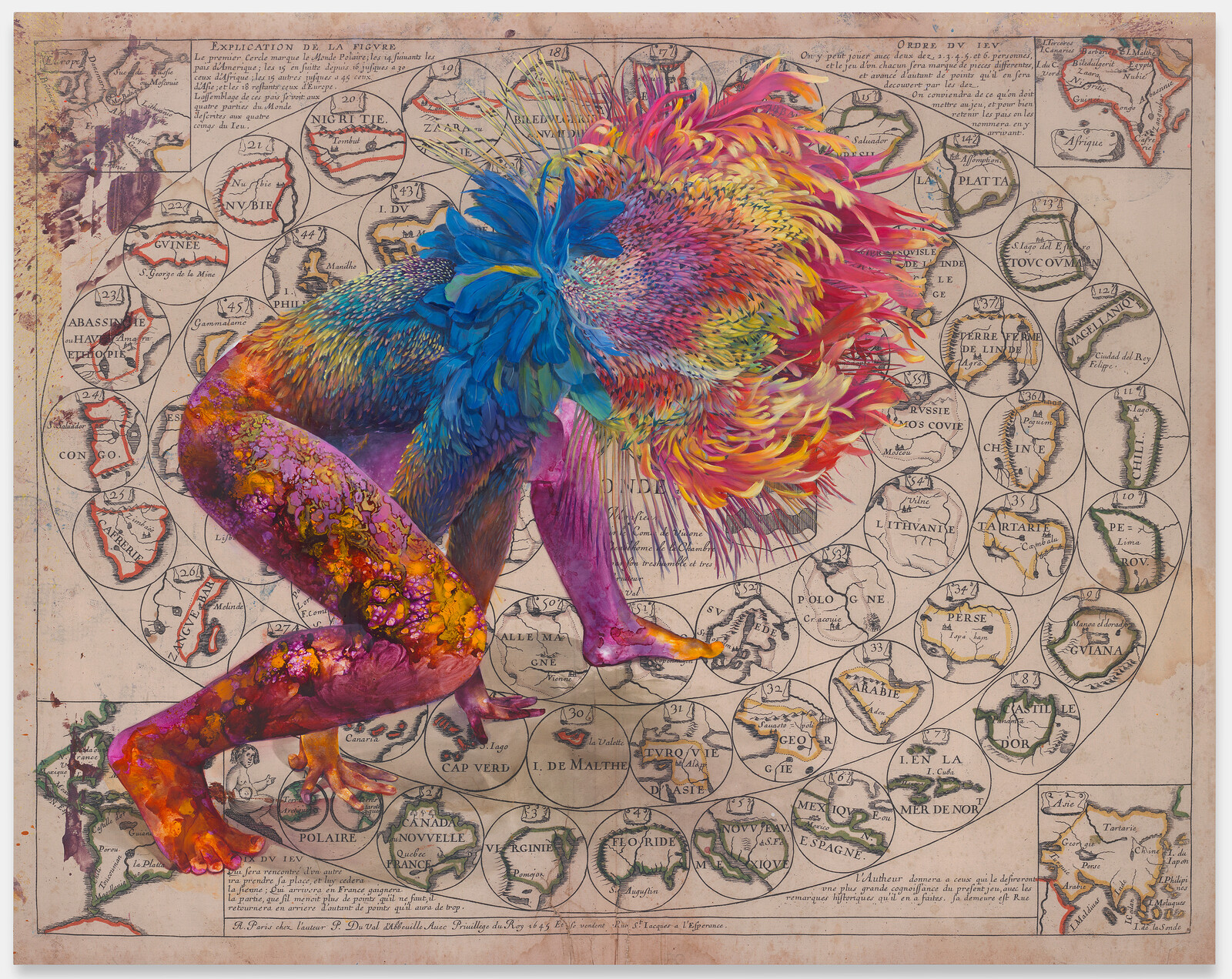

Firelei Báez: Trust Memory Over History

e-flux Announcement

Posted: June 26, 2024

Category

Borders & Frontiers, Migration & Immigration

Subjects

History, Diaspora

Institution

Nuit Blanche

Nuit Blanche 2024: Polygonal/e

e-flux Announcement

Posted: May 14, 2024

Category

Contemporary Art

Subjects

Diaspora, Postcolonialism

Institution

Galerie Barbara Thumm

María Magdalena Campos-Pons: I Heard the Spirits’ Voices

e-flux Agenda

Posted: May 2, 2024

Category

Religion & Spirituality

Subjects

Diaspora

Institution

PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art

Rajni Perera and Marigold Santos: Efflorescence/The Way We Wake

e-flux Announcement

Posted: May 1, 2024

Category

Migration & Immigration

Subjects

Collaboration, Diaspora

Institution

Issam Kourbaj

Tom Denman

e-flux Criticism

Posted: March 29, 2024

Category

War & Conflict

Subjects

Middle East, Memory, Diaspora

Croatian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Vlatka Horvat: By the Means at Hand

e-flux Announcement

Posted: March 27, 2024

Category

Migration & Immigration

Subjects

Diaspora, Networks

Institution

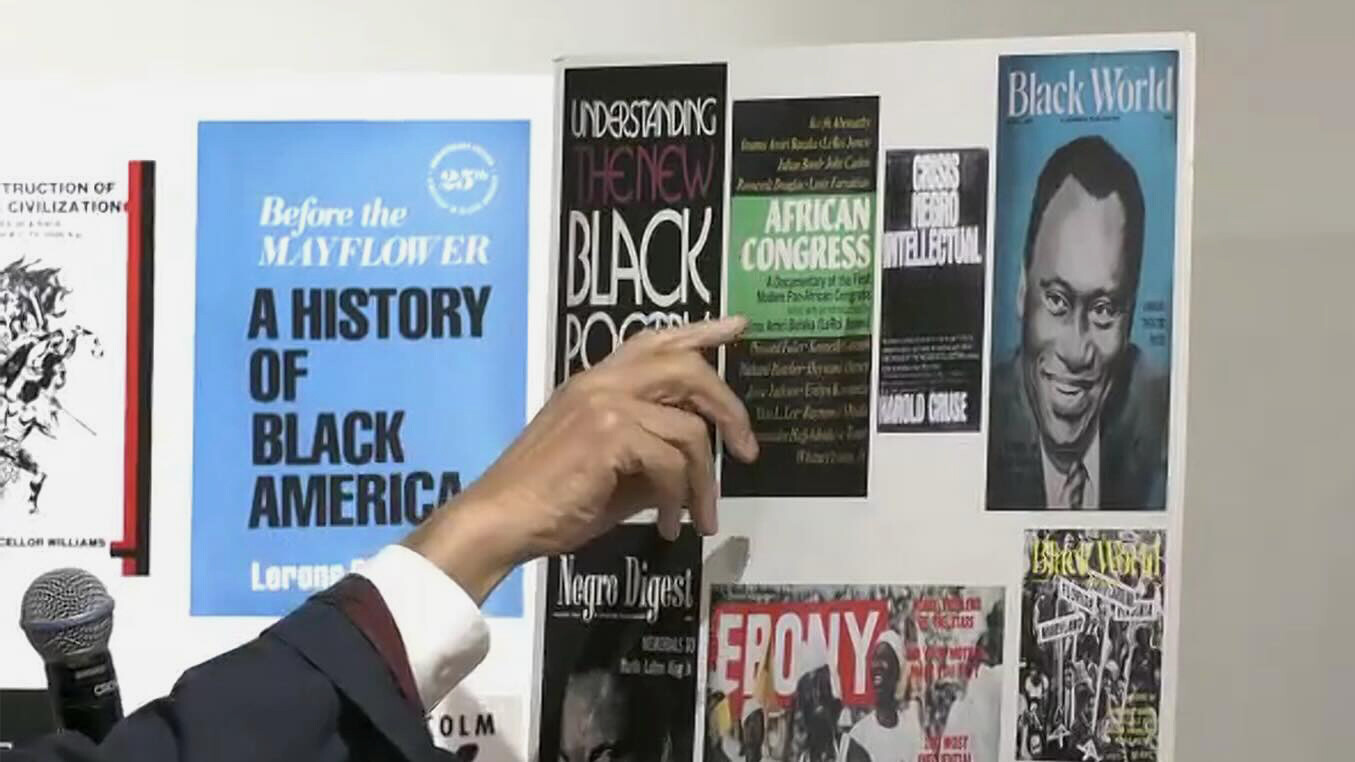

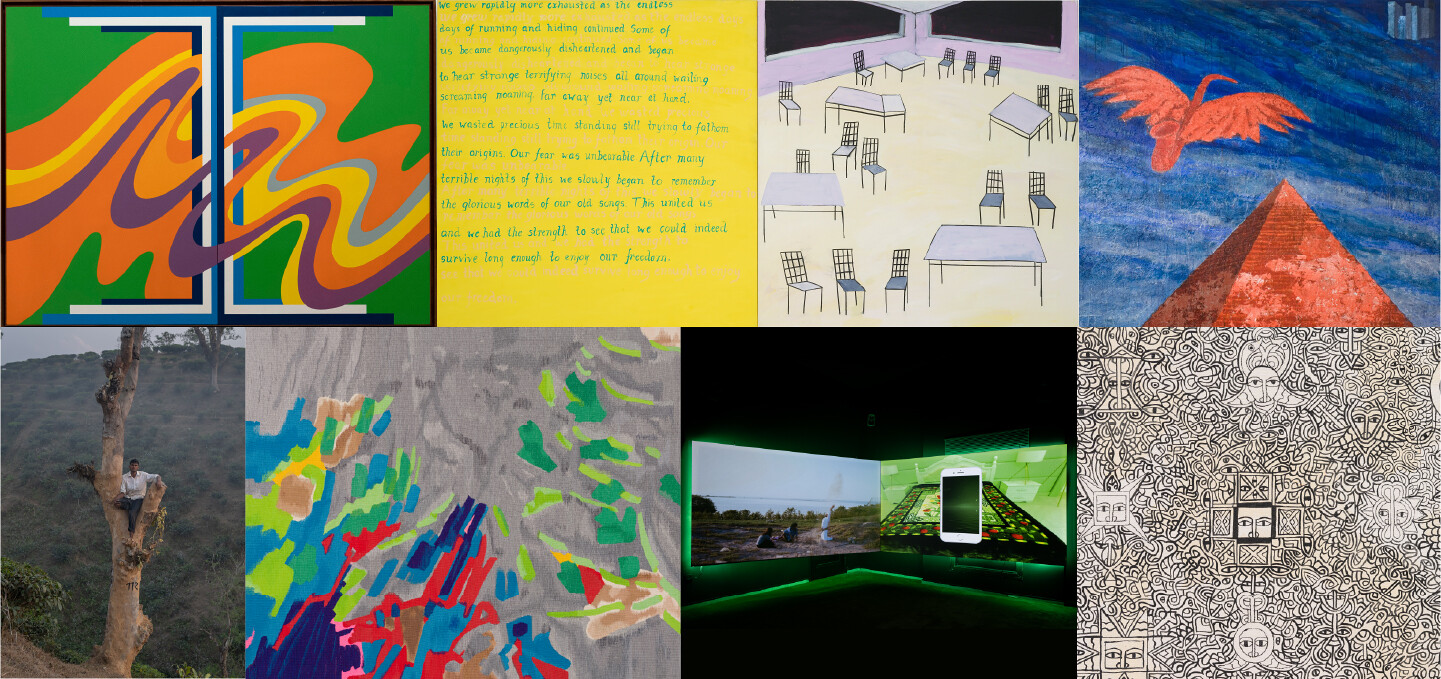

e-flux

Posted: March 20, 2024

Category

Education

Subjects

Africa, Diaspora, Black Power, Black Studies

Neuberger Museum of Art at Purchase College, SUNY

Virtual convening on African art in American museums

e-flux Education

Posted: March 13, 2024

Category

Museums

Subjects

Africa, Art History, Diaspora

The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

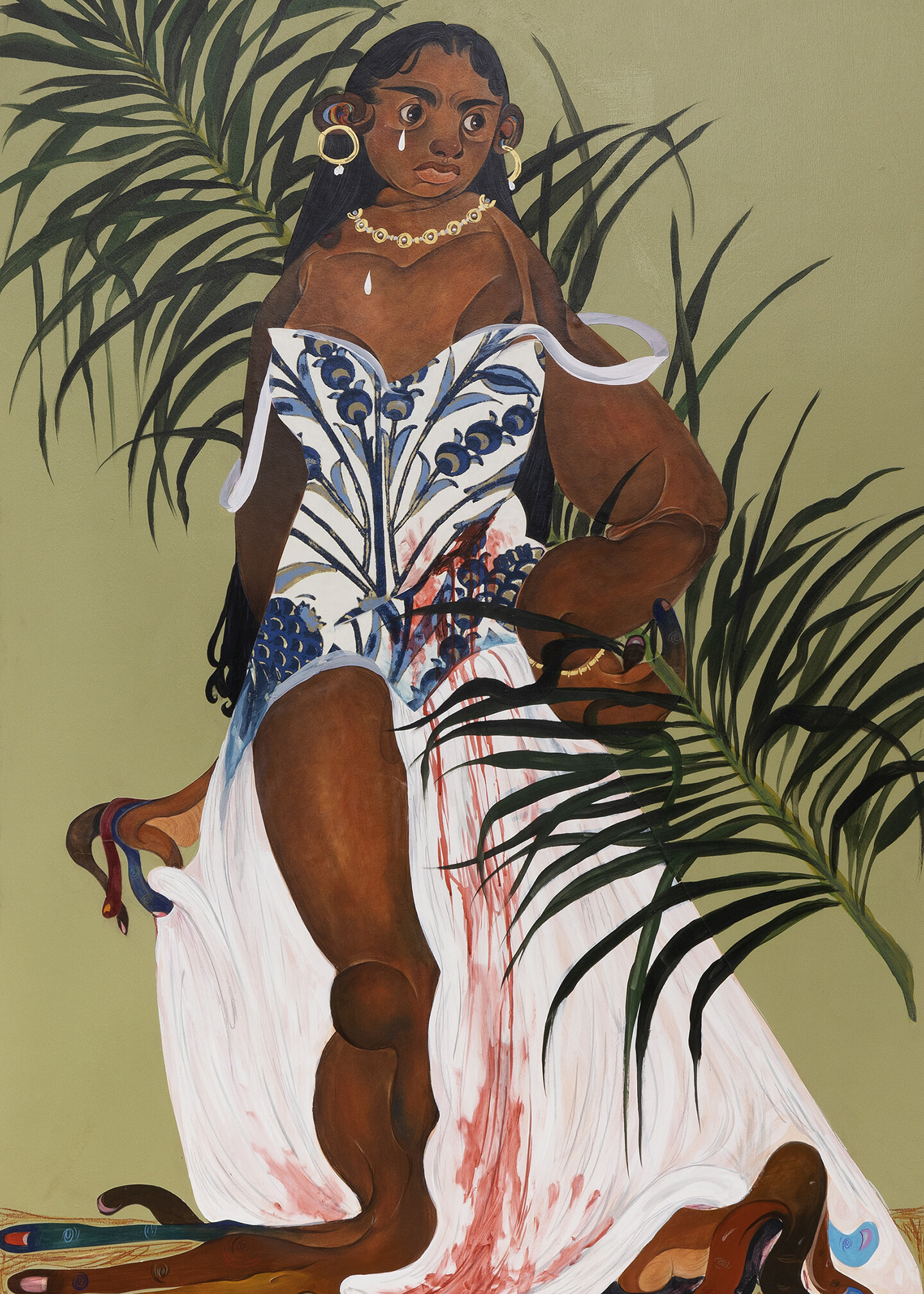

Surrealism and Us

e-flux Announcement

Posted: March 1, 2024

Subjects

Surrealism, Caribbean, Diaspora

Institution

e-flux Criticism

Posted: February 29, 2024

Subjects

China, USA, Identity Politics, Diaspora

Chilean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Valeria Montti Colque: Cosmonación

e-flux Announcement

Posted: February 26, 2024

Category

Migration & Immigration

Subjects

Citizenship, Diaspora

Institution

Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

Melike Kara: shallow lakes

e-flux Announcement

Posted: February 15, 2024

Category

Migration & Immigration

Subjects

Diaspora

Institution

University of Michigan Museum of Art

Angkor Complex

e-flux Education

Posted: February 1, 2024

Category

Colonialism & Imperialism

Subjects

Southeast Asia, Postcolonialism, Diaspora

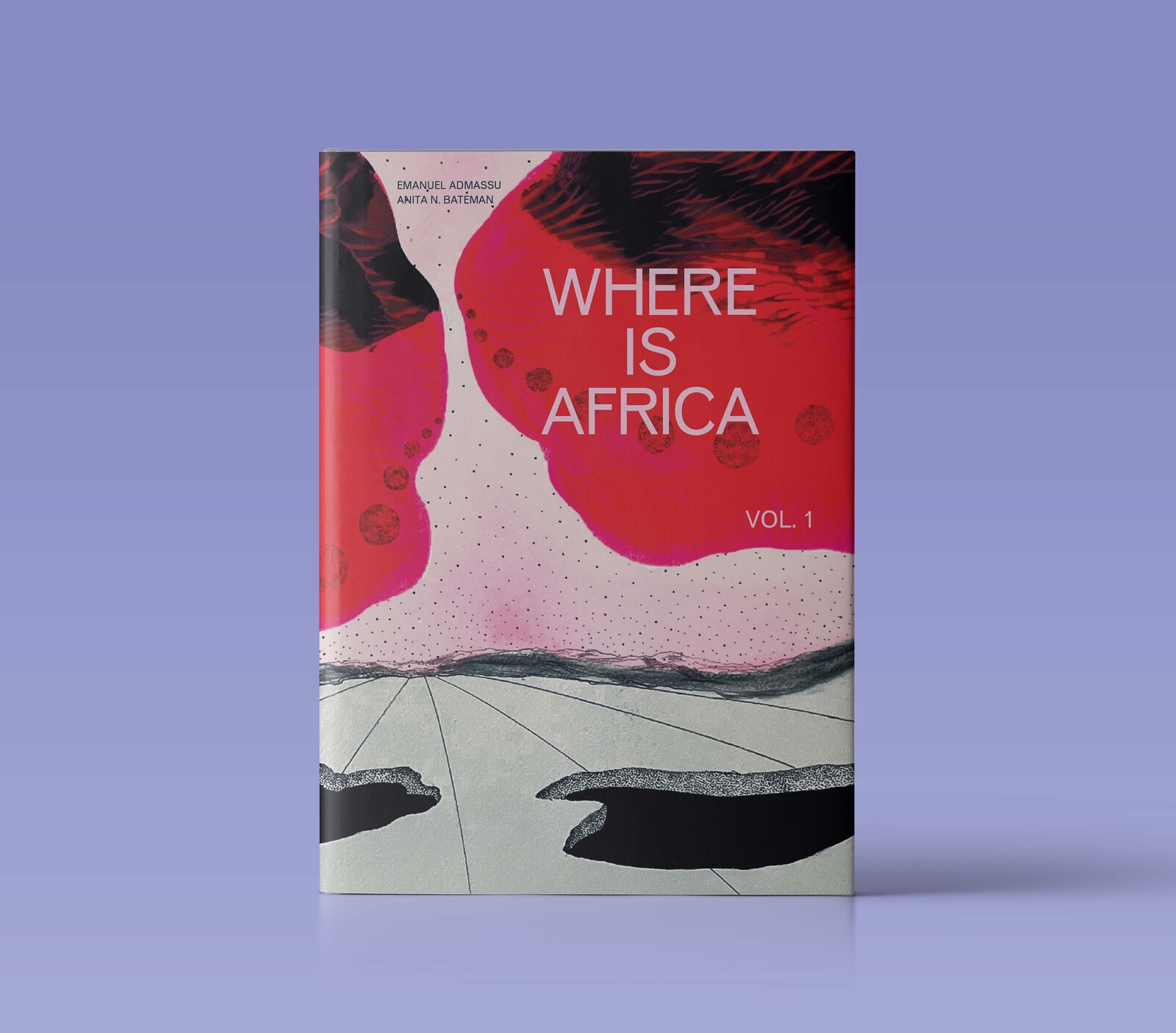

Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA)

Publishing Expanded: Where Is Africa

e-flux Announcement

Posted: January 8, 2024

Subjects

Africa, Publications, Diaspora

Institution

MAAT—Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology

MAAT presents its 2024 annual programme

e-flux Announcement

Posted: December 19, 2023

Category

Nature & Ecology

Subjects

Africa, Diaspora

Institution

IV INSTAR Film Festival

Miñuca Villaverde, Fernando Villaverde, Alejandro Alonso, Rafael Ramírez, and INSTAR

e-flux Events

Posted: December 9, 2023

Category

Film, Latin America

Subjects

Experimental Film, Documentary, Cuba, Diaspora

New York premiere: Charles Mudede, Thin Skin

Charles Tonderai Mudede

e-flux Events

Posted: November 30, 2023

Category

Film, Music

Subjects

USA, Diaspora, Family, Africa

e-flux Education

Posted: November 29, 2023

Category

Performance

Subjects

Africa, Diaspora

kurimanzutto

A Story of a Merchant

e-flux Agenda

Posted: November 28, 2023

Category

Colonialism & Imperialism

Subjects

China, Diaspora

Institution

Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo

Hands: 35 years of the Afro-Brazilian Hand

e-flux Announcement

Posted: October 18, 2023

Category

Latin America

Subjects

Diaspora, Exhibition Histories

Institution

Suneil Sanzgiri: Screening and Conversation

Suneil Sanzgiri

e-flux Events

Posted: October 17, 2023

Category

Film, Surveillance & Privacy, Colonialism & Imperialism

Subjects

Experimental Film, Video Art, Diaspora, Decolonization, Indian Subcontinent, Storytelling, Memory, Historicity & Historiography

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (ICA Miami)

Two new podcast seasons

e-flux Announcement

Posted: September 24, 2023

Subjects

Rituals & Celebrations, Diaspora, Caribbean

Institution

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul

Jung Yeondoo: One Hundred Years of Travels

e-flux Announcement

Posted: September 24, 2023

Subjects

Diaspora, Mexico, East Asia

Everywhere Was the Same: Pegah Pasalar, Mounira Al Solh, Basma al-Sharif, Suneil Sanzgiri, and Mirene Arsanios

Pegah Pasalar, Mounira Al Solh, Basma al-Sharif, Suneil Sanzgiri , and Mirene Arsanios

e-flux Events

Posted: September 12, 2023

Category

Film, Migration & Immigration

Subjects

Diaspora, Middle East, Southeast Asia

Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University

Uptown Triennial 2023

e-flux Education

Posted: August 30, 2023

Category

Music

Subjects

Diaspora

e-flux Announcement

Posted: August 10, 2023

Subjects

Domesticity, Diaspora, China

Institution

Connecting Diaspora: Short Films by Ephraim Asili

Ephraim Asili

e-flux Events

Posted: July 18, 2023

Category

Film, Resistance

Subjects

Diaspora, Africa, USA, Poetry

Sharjah Art Foundation

Summer and autumn 2023 programmes

e-flux Announcement

Posted: June 28, 2023

Category

Photography

Subjects

Diaspora, Africa, Postcolonialism

Institution