I. A Catalog of Catalogs

We are so lucky… We are so lucky to have been raised amongst catalogs!

— Meg Swan, Best in Show1

Growing up in the early 1990s, in the era just on the cusp of the internet’s inundating expansion into consumer culture and everyday life, it’s easy to recall the emotional thrall of expectation and inspiration that accompanied the arrival of any number of product catalogs in the mailboxes of our childhood homes. Whether in the mindless, euphorically aspirational pages of The Sharper Image catalog or the FAO Schwarz catalog, or in the comparatively more down-to-earth depictions of life found in the JCPenny catalog or the Sears catalog, each page depicted a horizon of possibilities on offer through consumption and presentations of class and status.

Chicago, where we both grew up, is the American birthplace of the popular mail order catalog. The mythic position of Montgomery Ward (established in 1872) and Sears, Roebuck and Company (established in 1892) is still evident today in its shared imagination as the industrious and influential “City of Big Shoulders.” The centrality of the mail order houses is even apparent in the built form of the city itself. SOM’s Sears Tower, completed in 1973, is an ever-present indicator of the apex of the company’s influence and capacity to structure the world around us; a sort of highwater mark of Sears’s apparently immutable presence (an impression that was exposed, in fact, as considerably mutable, with the renaming of the tower in 2009).

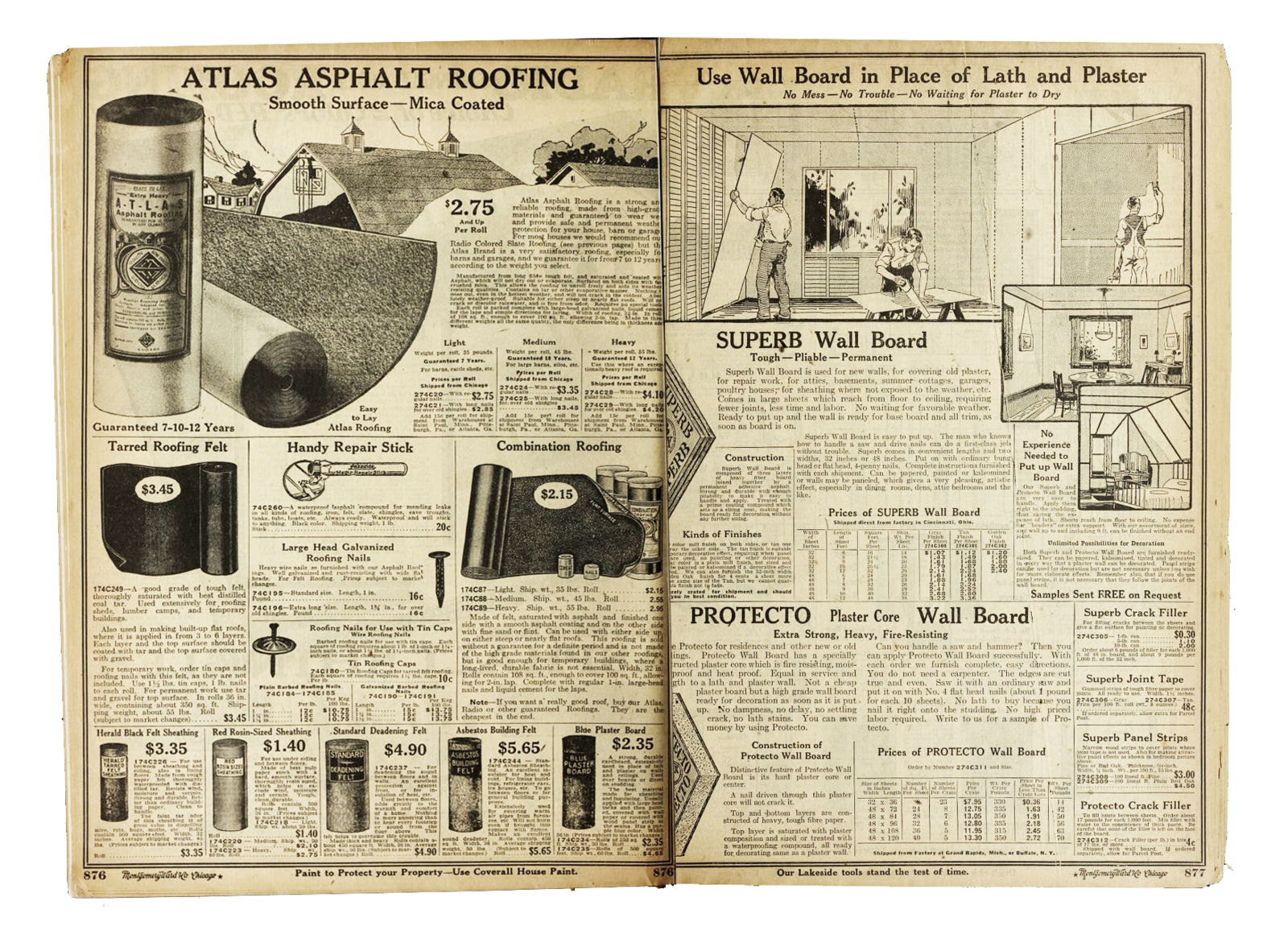

In typical retellings of the Montgomery Ward and Sears stories, the decisive aspect in each’s business strategy was the predictability and uniformity that the mail-order catalog offered to customers, and the sense of trust that it enshrined in large-scale commercial institutions. For so many rural consumers in the late nineteenth century, we are told, general stores were limited in goods and their pricing wasn’t reliably fixed. By committing to the dimension, weight, description, and most importantly the price of each product, the mail-order publication, as a material artifact itself, seemed to embody any number of oaths and mottos that peppered their pages. “Nowhere else can you find such a variety of things at such reasonable prices.”2

Whether a page from the 1920 Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue & Buyers’ Guide or a screengrab of some notable or notorious products available on Amazon today,3 what makes the catalog so compelling is its capacity to suggest a narrative around any number of lifestyles or possible ways of being in the world. And as Thomas J. Schlereth notes, we can regard these publications as documentation of the broader impacts of rapid industrialization in the American cultural landscape: “The search for order, efficiency, rational planning, automation, and high productivity is nowhere more graphically or unashamedly portrayed than in successive catalogs containing detailed descriptions and illustrations of these Chicago firms’ growth in national business.”4 Reyner Banham echoes this point in an article about the centrality of the portable mechanical gadget in American culture: “The Sears catalogue is one of the great and basic documents of US civilization, and deserves the closest critical study wherever the state of the Union is discussed.”5

It would seem to follow that by combining and correlating these documents, we could discover an even richer set of meanings and associations in the similarities and differences between them. Yet flipping through all 267 pages of Random House’s endearingly titled 1973 Catalogue of American Catalogues provides only disappointment, a lackluster lens with which to understand American life in the 1970s.6 Sure, there’s a very promising Borgesian ambition in the book’s title, and the table of contents includes no fewer than sixteen subcategories under the heading “House,” but beyond a few noteworthy juxtapositions (like a spread featuring both a chewing gum vending machine and an eighteenth-century Russian icon of the Virgin and child),7 the lesson here seems to be that brevity is not the soul of a catalog, rather tediousness. This is embedded in the word’s origins in Greek: kata- for down, completely, and -legein, to say, count.8 The catalog tells a more engaging story when it reflects a willingness to accept the daunting challenge that its name entails: to get everything down completely. So much was, at least, proclaimed on the cover of the Montgomery Ward catalogue: “Supplies for every trade and calling on earth.”9

Toward this end, another formative reference point in the canon of catalogs can be productively misread: the Whole Earth Catalog. Synonymous with the American back-to-the-land movement that emerged in the mid-1960s, what could it mean to take its title at face value, with the exhaustive hubris that its language and cover imagery implies? One category within that endeavor started just as the Whole Earth Catalog issued its last regular edition: a distinctly different architectural indexing project. Whereas the Whole Earth Catalog was interested in elevating vernacular, accessible, design-build methodologies in architecture and construction that anyone could participate in, what we might call the “Whole Architecture Catalog” was motivated to make architectural design more specialized, technical, and integrated with building systems in a totalizing vision of what large-scale construction and globalized circulation of building products and services could achieve.

II. The Whole Architecture Catalog

We’ve all lived a life thinking that drawings were the representations of buildings.

— Charles Eastman10

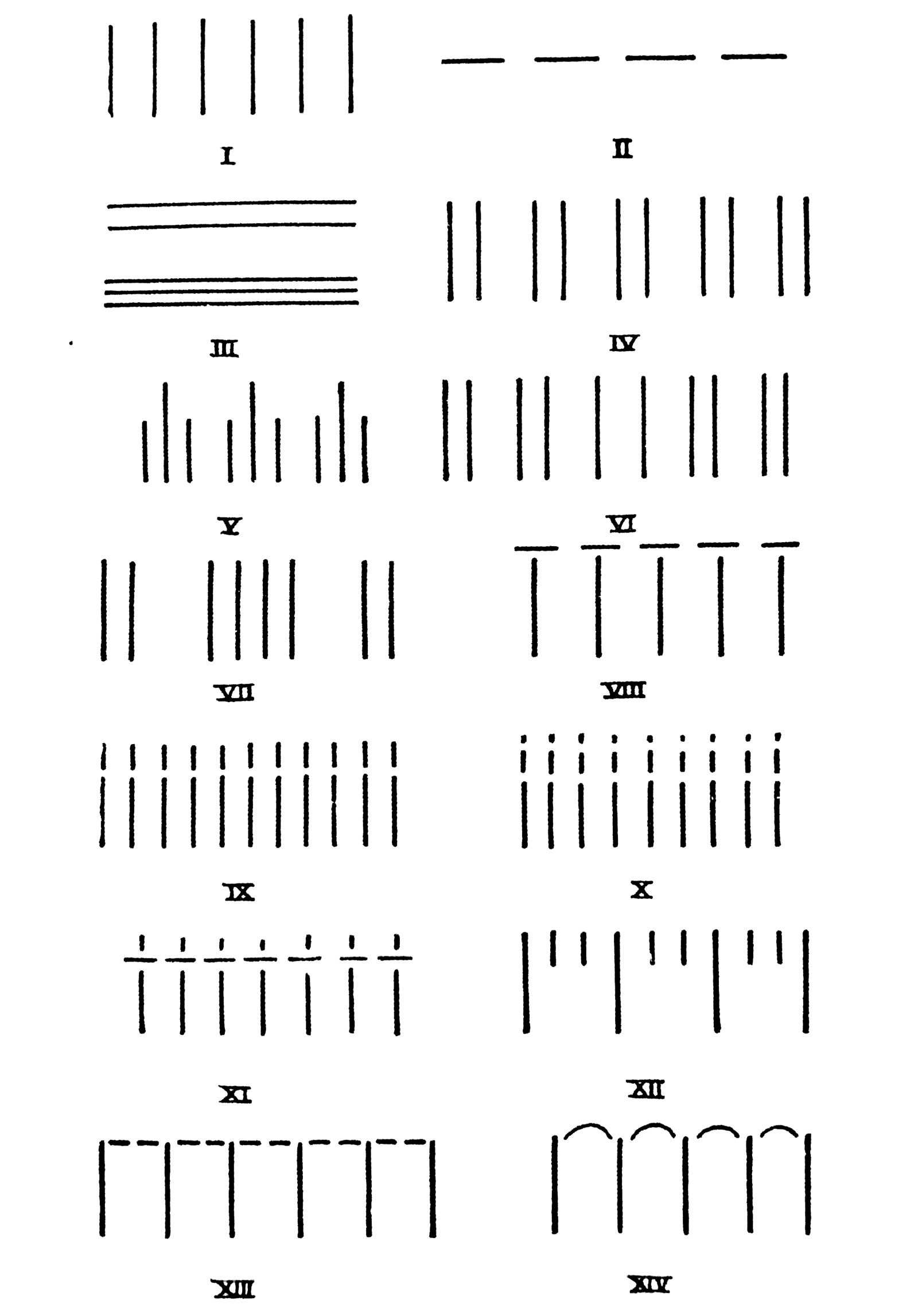

In the mid-1970s, the potential applications for computer-aided processes in design were becoming increasingly apparent, and the role of digital interfaces in architectural workflows began to appear more and more inevitable. Two approaches were articulated that would inform the ideation and depiction of built work for decades to come. The first, which rose to prominence through the 1980s and 1990s, took the drawing itself as the central evidentiary reference point.11 And as personal computers found their way into the office, and then into personal spaces, black backgrounds and delicate tracings of lines and planes within multi-paned CAD interfaces became the dominant interactive means through which design turned into plans, details, and drawing sets.

By contrast, and lurking largely outside the architectural office, in labs and academia, an alternative approach regarded drawings as simply a side effect, a vestigial artifact of a no longer necessary work process. “Drawings are an integral part of architectural practice,” Charles Eastman succinctly states in the first sentence of a 1975 article articulating this approach, only to follow a moment later with the cognitively dissonant rejoinder: “drawings have no intrinsic value in architecture.”12

With a background in architecture, Eastman’s work in the 1970s was focused on the development of digital design tools. Widely regarded as a pioneer of Building Information Modeling (BIM) systems, with teams that he directed at Carnegie Mellon University, his research proposed the emerging potential for what he then called a Building Description System (BDS).13 Just as Montgomery Ward and Sears had given definition and specificity to an emerging national consumer identity almost a century earlier through the dissemination of items with reliably fixed product codes, dimensions, and prices, this proposed architectural catalog would similarly standardize a way of architectural practice through digital tools. His early research papers offered a computational output that could use data-laden “elements” and “templates” in place of semantically and functionally ambiguous lines of architectural drawings. The BDS that Eastman and his team describe in 1975 insists that no rectangle should simply be a rectangle, but rather a piece of dimensional lumber, a steel beam, or a pipe; rather than drawing a primitive, “the user need only ask for a ‘WF14122.’”14 Similarly, BIM software today insists that no surface is only a surface, but rather a wall, a roof, or a floor.

“A different way of thinking about design is encouraged by [the Building Description System],” Eastman ominously remarks. By virtue of the limitless varieties for visual representations that it offers, and by explicitly connecting the design process to actual construction materials, he goes on to note that this more “thorough” and “realistic” architectural depiction gives rise to a “new mental perspective.”15

III. Buildings as Catalogs

As opposed to the traditional hasty sketch, the assiduously drawn plan, or the carefully assembled model of a proposed building project, the BDS or BIM file innately carries with it the description of its constituent parts. It is, in a sense, the perfect embodiment of that anxiety provoking experience so common in digital spaces; the dawning realization, as you approach the bottom of a page, that there actually is no bottom. Rather, it scrolls on endlessly, populating more and more content, details, results, and information than you will never have the time or mental capacity to put to use.

In BIM software, the promise of associative links and reference elements offers a totalizing solution to the frictions, compromises, and negotiations that have been central (or not, depending on the historical perspective) to contemporary architectural practice. Moving from concept to drawing to built form has typically necessitated an understanding and intimate relationship with labors, trades, and crafts that is rarely, if ever acknowledged in architectural discourse. From foundation to framing to finishes, moldings, and layers of paint, each practitioner, whether consciously or not, asserts, smuggles, or surrenders their own agency in each step.

The “new mental perspective” that Eastman identified seems to suggest that the option, to either acknowledge or ignore the compromises and translations between drawing and building, is no longer valid. In BIM, every detail of the architectural drawing can be embedded with its supplier, attributes, and performance specifications. Whether wittingly or willingly, the architect seemingly takes on the role of the contractor while creating the model. The digitally specified line is no longer simply a representation of a wall, but rather an “Owens Corning - CavityComplete® Steel Stud Wall System.”16 A door is a “TORMAX USA Inc. - TX9600TL Manual Swing Healthcare Door System.”17 And a floor is a “Maxxon® Corporation - Therma-Floor® Gypsum Underlayment.”18

Contemporary architectural practice has been propped-up by a reliance on specifications and descriptions to distinguish experts from laypersons. A comprehensive knowledge of ARCAT or the Sweets Architectural Catalogue (or at least the presence of a well-worn copy on one’s bookshelf) was once a critical distinction that served to define architecture as a privileged and specialized discipline, beyond the reach of non-professionals. First compiled as a reference publication for builders in 1917 in Boston, and later expanded in partnership with the publisher of Architectural Record,19 Sweets’ 2012 edition was the last to be distributed in print, and today exists exclusively as a digital repository for architectural components and parts.20 The mental archiving and practiced recall that once served as proof of professional competency resides today largely in drag-and-drop components, drop-down menus, radio-buttons, checkboxes, folders, and sub-folders.

All catalogs and indexes of this sort are aspirational in one sense or another, offering instructions on how to acquire or achieve some ideal, whether explicitly stated or teasingly implied. Whether it be Sears, Whole Earth, or Sweets, each catalog offers the promise that the reader’s desired outcome is measurable, quantifiable, and graspable through the prescriptive attainment and combination of constituent parts. What both digital warehouses and product catalogs share in common is the capacity to unpack the end product, and a cavalier, even irresponsible relationship to agency in the outcome. In the same way that Stewart Brand now remarks on the negative impacts of self-sufficiency and libertarianism embedded in the Whole Earth Catalog, and its influence on the cultural agenda of Silicon Valley today,21 it is tempting to expect Eastman to acknowledge some onus for the purported uninspired and unimaginative quality of many large-scale buildings designed and constructed in America today, the majority of which are developed with BIM. Such an acknowledgement, however, seems unlikely.

Eastman’s work embraced the operational potential that came with indexing and enriching each component with a set of relational values and implications. The catalog, in this sense, is also an exercise in clarification. It takes a broader objective (typically consumer capitalism, but perhaps also holistic communal living), and breaks it down into a set of component pieces; a kit-of-parts for that broader objective. Like the distinction between simple markup and executable code, his BDS project turned the building from an assemblage of independent parts into an ecology of interrelated pieces. In Autodesk Revit, for instance, one of the most prevalent BIM system in use today, if the HVAC needs to be adjusted, the plumbing can be made to dynamically shift to accommodate the change, and electrical made to update in sequence. Thus, while the effort to catalog and collect may initially appear to be an effort in deunification—to separate the whole into the many—after the digital turn, with informationally and descriptively enriched elements, it achieves the opposite.22

In quantifying, measuring, comparing, and budgeting every conceivable aspect of the building project, BIM systems have indeed given way to the “new mental perspective” that Eastman foretold, but perhaps in a way that he would have found disconcerting. The disciplinary creep that such systems usher into the office have precipitated a crisis in architectural practice, where designers are less engaged with and accountable to issues of form than to the relationships between trades, systems, and their performance. The reduced paperwork, labor costs, and unnecessary revisions that BIM integration promised for many large-scale architectural offices in the early 2000s, regularly characterized by the efficiencies of scale and production achieved in the One World Trade Center (née Freedom Tower) project, is only beginning to play out in the arrangement and organization of the contemporary architecture office, or to become formally apparent in the built environment itself.

Common criticisms of the impact and influence of BIM on contemporary architectural practice largely focus on its perceived deficiencies as a creative tool for form-making. Other software programs, like Robert McNeel & Associates’ Rhinoceros 3D, have become synonymous with intuitive, even mindless excesses of material and structural experimentation. But BIM environments, and Revit, in particular, seem to not only incentivize, but to make inevitable a formal and logistical output more akin to the spreadsheet than anything else. With its emphasis on budgeting, scheduling, and construction management, arguably at the cost of novel and engaging formal and spatial arrangements, perhaps it’s no wonder that one of the primary motivators in the transition to BIM that happened at the turn of the century was the US government’s predilection for the efficiencies and cost-savings that a BIM approach would incur.23

IV. What’s Missing From BIM’s Totalizing Worldview

What would it mean for a BIM system to not only account for the roles of engineers, electricians, plumbers, and HVAC technicians in the process of architectural design, but the general public as well?

A better example of the untethered and unregulated DIY possibilities of the BDS approach can still be found, if only in slight glimpses, in Trimble’s 3D Warehouse.24 Initially acquired by Google in 2006 as part of its efforts to leverage SketchUp as a tool to quickly and cheaply produce a digital model of the entire surface of the earth,25 today 3D Warehouse is a Frankenstein’s monster of slapdash hobbyist projects and models of industry-oriented fixtures, furniture, and fittings. Here, in the disregarded and dusty corners of the 3D Warehouse, are one-offs and one-liners still pulsing with the promise of what digital description and careful delineation would bring to the world. “COLLABORATE” screams a headline on the company’s website, touting the benefits of designing with SketchUp in conjunction with 3D Warehouse. “Get inspired,” it continues in the subheading, referring to the ability to easily browse or search for specific features and details among any number of collections and catalogs of commercial products and user generated models. “Share with the world,”26 it concludes, enticing users to upload their own 3D models to the Warehouse and potentially garner likes, views, or comments, such as “what is that how the heck did you make that??????????????”27

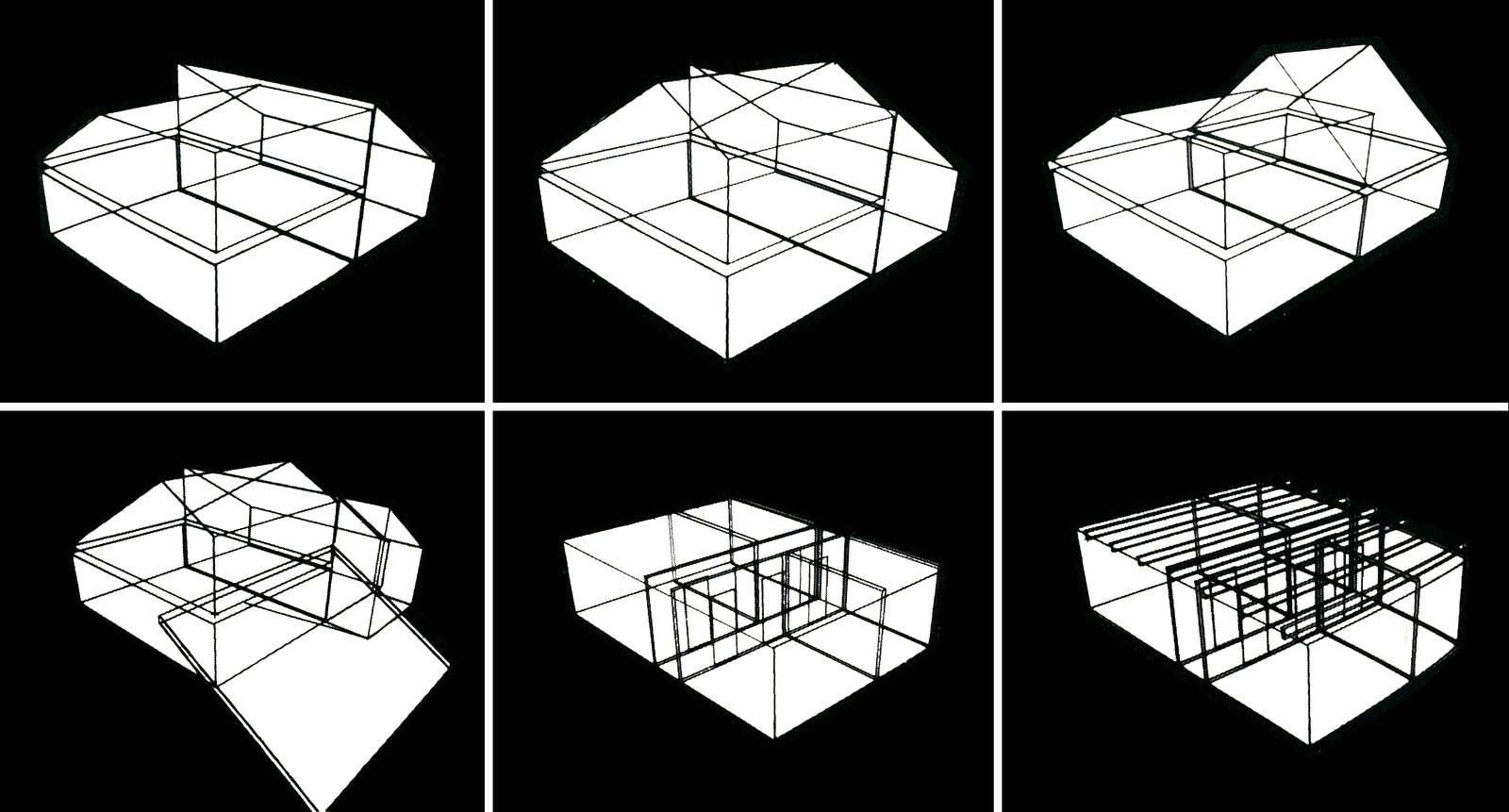

Erin Besler and Ian Besler, House1.skp and House2.skp, 2014, single-channel video, from United States Patent No. 6,628,279 B1, “System and Method for Three-Dimensional Modeling” by Brad Schell, Joe L. Esch, and John E. Ulmer.

Examining the patent documentation filed by Brad Schell, Joe Esch, and John Ulmer in 2000 for a “System and method for three-dimensional modeling” provides a stop-motion playthrough of the “Exemplary Design of A House” for a pair of rudimentary digital designs.28 These illustrations could be regarded as documenting the creation of the primordial ur-models of 3D Warehouse, the Adam and Eve, in this case House1.skp and House2.skp. The designer first draws a plane in one file (“House1.skp”), the archetypal five-sided house elevation, then adds depth and articulation to the form to create a roof hip and a set of five dormers. Apparently bored by this design approach, a new file is created (“House2.skp”), with a similarly iconic house model as the outcome, this time making use of the push/pull extrusion tool for generating dimensional form, followed again by some fussy articulation. Finally, as a simple gesture of mise-en-scène, a bench is created through the combination of four rectangular slabs, as if absent-mindedly pieced together while fiddling with the rotation tool in the software.

This “Exemplary Design of A House” included with the SketchUp patent filing, and the story that it tells about the intended designer and their design process, is a catalog. In its capacity to suggest certain priorities for architectural design (detached single family housing) in conjunction with a set of technological and interface competencies, it embodies a similar projection of aspirational lifestyles as Sears, Montgomery Ward, Sweets, or Whole Earth. But viewed in opposition to the totalizing and comprehensive ambitions of the BDS approach, this feels refreshingly accessible, as something deserving of the adulation “very coool” posted in the comments, along with a like.29

Collections on 3D Warehouse of “my first model” (1,000+ items),30 “my desk” (295 models),31 and “my house” (1,000+ items)32 all carry with them the embedded assumptions and agencies of the modelers involved. While distinctly lacking in the networked potentials of suppliers, attributes, and specifications (here a plane is still very much just a plane), there is still a funny impression that one eventually arrives at while scrolling through the catalogs of models, desks, and houses in 3D Warehouse. Some are painstakingly earnest, some totally incomprehensible. Rather than insisting on the inevitability of formal output and eventual construction, each seems to acknowledge and lavish in the potential of impossibility. In apparent opposition to Eastman’s assertion of the “new mental perspective” that description and information modeling could afford, each seems to relish the lack of accountability in how untethered they are to the externalities of supply chains and resource allocation. Each is simply a trophy of the self-taught imperative offered at the conclusion of The Last Whole Earth Catalog: these digital models seem to both stay hungry and stay foolish.

Best in Show (dir. Christopher Guest, 2000, Castle Rock Entertainment), ➝.

Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue & Buyers’ Guide 1895: Unabridged Facsimile (Skyhorse Publishing, 2008), 562.

See, for example, the recent removal of Auschwitz-themed mouse pads, bottle openers, and Christmas tree ornaments from the retailer’s website: Jennifer Hassan, “Amazon pulls Auschwitz-themed Christmas ornaments, although other Holocaust merchandise remains on site,” The Washington Post, December 2, 2019, ➝.

Thomas J. Schlereth, “Mail Order Catalogs as Resources in American Studies,” Prospects 7 (October 1982): 145.

Reyner Banhman, “The Great Gizmo,” Design By Choice, ed. Penny Sparke (Academy Editions, 1981), 110.

Maria Elena De La Iglesia, The Catalogue of American Catalogues (Random House, 1973).

Ibid, 11.

“Catalogue,” Online Etymology Dictionary, ➝.

Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalogue & Buyers’ Guide 1895: Unabridged Facsimile (Skyhorse Publishing, 2008), cover. Emphasis added.

“Chuck Eastman Building Information Modeling and Performance Based Design,” University of Idaho College of Art & Architecture - Department of Architecture and Interior Design, October 13, 2008, ➝.

See, for example: Robin Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (MIT Press, 1997).

Charles M. Eastman, “The Use of Computers Instead of Drawings In Building Design,” AIA Journal vol. 63, no. 3. (March, 1975): 46–50, 46. ➝.

At both the Center for Building Science and the Computer Graphics Lab.

Charles M. Eastman, “The Use of Computers Instead of Drawings In Building Design,” AIA Journal 63, no. 3 (March, 1975): 49. ➝.

Ibid, 50.

Sweets, “Owens Corning - CavityComplete® Steel Stud Wall System” ➝.

Sweets, “TORMAX USA Inc. - TX9600TL Manual Swing Healthcare Door System,” ➝.

Sweets, “Maxxon® Corporation - Therma-Floor® Gypsum Underlayment” ➝.

Cecil D. Elliott, The American Architect from the Colonial Era to the Present (Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 61 ➝.

Steven Heller, “The Last Sweets Catalog,” Print Magazine, December 15, 2014, ➝.

Anna Weiner, “The Complicated Legacy of Stewart Brand’s ‘Whole Earth Catalog’,” The New Yorker, November 16, 2018, ➝.

See, for instance: The Digital Project Suite, ➝.

Various federal agencies provide overviews, guides, and requirements for BIM adoption at their websites, such as: the General Services Administration, ➝; the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Construction & Facilities Management, ➝; and the CAD/BIM Technology Center at the US Army Engineer Research and Development Center, ➝.

Trimble, Co. “3D Warehouse,” ➝.

Trimble acquired the platform back from Google in 2012 when the company relinquished the human-generated element of its plan, opting for the more computationally oriented approach of photogrammetric interpolation.

Trimble Sketchup, ➝.

Benjamin D. Re: โบสถ์ประหยัด, ➝.

Schell first developed CADZooks, a software that simplified construction drawings. CADZooks would later be acquired by Autodesk. Schell and Esch later founded @Last, which developed SketchUp prior to the product’s acquisition by Google. Brad Schell, Joe L. Esch, and John E. Ulmer, United States Patent No. 6,628,279 B1, “System and Method for Three-Dimensional Modeling,” Nov. 22, 2000. 164, ➝.

Ethan S. Re: Fishing Boat, ➝.

Trimble 3D Warehouse, “Search: ‘my first model’,” ➝.

Trimble 3D Warehouse, “Search: ‘my desk’,” ➝.

Trimble 3D Warehouse, “Search: ‘my house,” ➝.

Intelligence is an Online ↔ Offline collaboration between e-flux Architecture and BIO26| Common Knowledge, the 26th Biennial of Design Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Category

Subject

The authors would like to thank Sarah Hearne.

Intelligence is an Online ↔ Offline collaboration between e-flux Architecture and BIO26| Common Knowledge, the 26th Biennial of Design Ljubljana, Slovenia, within the context of its exhibition catalogues.