monster

From monstrum, monere: to show, warn, or remind

by which gods give notice of calamityHence:

monstrous

premonition

demonstration

monumentfugue

From fugere, or fugare, to flee from or chase,

as in fleeing or chasing monsters or ghosts.

Fuga the act of flight.Fugues appear in contrapuntal music or narratives, interweaving differently braided voices.

Fugues also appear as emotional states involving amnesia, great forgettings and unburyings,

where one finds oneself unexpectedly in haunted spaces that create improbable connections.Hence:

refugee

fugutive

refuge

to fly

We have entered an epoch of shocked space and torn time. How do we write a history of fragments? How do we record a history of forgetting?

This essay enfolds, fugue-like, three great crises of our time: climate chaos, global militarization, and the mass displacement of people and other species. The established circuits that connect these crises have been ghosted. Origins are never originary. Something has always gone before. How can we account for the planetary upheavals of the Anthropocene unless we illuminate the long arc of their beginnings in the military geographies of European imperialism—the foundational violences of slavery, genocides of Indigenous peoples, and the centuries of ecocides and onslaughts on the environment that shaped—and are now undoing—the world? At the same time, how can we animate alternative histories of the past and thereby imagine alternative futures?

The planet is awry. We awakened oil from its ancient slumber to fuel our own fossil dreams. We combusted the deep time of the past—aeons of compressed ocean shells, ancient plants, and animal bones—into an alchemy of black energy and our fantasy of a forever fossil future. Now the ice sheets are vanishing faster than ever thought possible. Greenland is melting. The ice is leaving Iceland. Lightning torches the tundra, turning permafrost into permafire. Firestorms so vast they are visible from space rage across Amazonia, Australia, Siberia. In Harare, Zimbabwe, the taps run dry. Farmers watch mile-high dust storms rub out the sky. The great burnings of the trees, the vanishing of the bees, and everywhere the stealthy rising of the seas.

How do we live in fugue times?

A men’s clothing shop in Izmir, Turkey, selling life jackets. Photo: Tyler Hicks/The New York Times/Redux, September 26, 2015.

Fugue I: Refugee

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the landNo one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying-

leave,

run away from me now

i dont know what i’ve become

but i know that anywhere is safer than here

—Warsan Shire, “Home”

In 2015, at the height of the arrival of 500,000 displaced people into Europe, a men’s clothing shop in Izmir, Turkey, began selling orange life jackets alongside its regular men’s wear.1 Izmir serves as a hub for refugees and migrants, as well as a boomtown for local business. A photograph of the shop is both striking and chilling in showing how nonchalantly the shop-window stages a false equivalence between the models on the right wearing orange life jackets and the identical models on the left wearing black business jackets. As if displaced people from the global south, desperately dressed for survival, can, with the exchange of cash like the man tucking his wallet in his pocket, pass through the open door of the unregulated free market, risk-and-security economy, be rescued from calamity, and instantly dressed for success.

The shop window stages the false promise of the neoliberal, masculine, equal-opportunity market, a contemporary version of the imperial rescue narrative, choreographing global-south to global-north upliftment: “the free market that will raise all lifeboats” ethos. But the black hole of the rubber tube in the window and an orange chaos of piled up life jackets just visible at the back of the store create visual disturbances that point to a spectral violence.

Ghosts point to places where concealed, denied or unresolved violence has taken place.2 The administration of forgetting—the calculated, administered, and often brutal amnesias by which a state or political entity tries to erase the secrets of its violence—nonetheless leaves telltale traces as a kind of counter-evidence. Violence seldom erases what it effaces; it leaves shadows of what it tries to encrypt.

In Izmir, the “dark secret“ is that a shadowy, multi-million-dollar raft economy is booming: a smuggling infrastructure of makeshift insurance offices, expensive water taxis to Greece, and factories churning out life jackets and inflatable rafts. The inadmissible crime is that the life jackets are mostly made from materials like foam that do not float, but absorb water, potentially drowning rather than rescuing the refugees.

The New York Times article that accompanies the photograph is, like neoliberalism itself, awash with obsessively watery words.3 Migrants are flooding. A human tide is rushing. Money is pooling. Cash is pouring. Outflows and overflows. “It’s a perfect storm,” says Demetrious Papademetriou, President of the Migration Policy Institute Europe. The watery words obscure the migrant calamity (as well as the profits garnered by the pirates of peri-capitalism and the overlords of austerity) as a tidal result of natural causes. Nature becomes the alibi and accomplice of the inequities of austerity; the Great Divide separating the tiny sliver of the global mega-rich from the billions of the catastrophically poor is figured as a fiat of nature. As Arundhati Roy notes, trickle down hasn’t worked. “But Gush-Up certainly has.”4

What the article obscures is that the majority of refugees arriving in Turkey were from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria: the shattered revenants of illegal US wars of occupation that both caused, and converged with, the accelerating catastrophes of climate breakdown and mass displacements.5 Militarization is the largest single cause of environmental destruction in the world.6 The US military is the largest single cause of conflict in the world. And by January 2019, an unprecedented 70.8 million people have been displaced, 68.5 million by armed conflict or persecution.7 A person is forcibly displaced every two seconds somewhere in the world.8

But displacement is not merely the violent removal of people and other species from place. Displacement is also the removal of place—the loss of place in place—manifest in damaged ecologies like melting ice caps, felled trees and forest infernos in Amazonia, trees torched for palm oil plantations in Indonesia, bleached coral reefs, fraying wetlands, toxic rivers, and the rising oceans of this blue planet we are slowly undoing.

Seeing displacement as both removal from place and removal of place invites us to consider forced mobility as the spectral double of forced immobility. Millions of the global poor and dispossessed are either forcibly on the move or incarcerated in migrant camps, border detention centers, ghost prisons, and island prisons (like Nauru, off Australia); webbed into the invisible surveillance systems of carceral modernity that now spreads its filaments around the world.

Fugue II: Premonition

Glacier, a puddle.

Glacier, a monsoon,

a tsunami.

Glacier, a plaque,

a siren.

—Jen Rose Smith (Eyak), “Cryogenics”

It is the summer of 2012 and I am flying over Greenland. Far below lies an unearthly landscape. Something looks beautifully, surreally wrong, but what is it? Greenland’s mountains are sloughing off their ancient sheath of snow. The icy tongues of the glaciers are thinning. The bony ribs of the earth are visible to the sun for the first time in 100,000 years.

2012 is the Goliath year of climate change, and it is all about the ice. But one fact towers above the rest: the colossal melt of Greenland. In mid-July, scientists stared at statistics so staggering they thought at first there was some mistake.9 Satellite images showed that in four days alone, 97% of the massive, mountainous surface of Greenland had melted from white to dark.”10 Snow cover, parts of which had been frozen for eighteen million years, had thawed into a colossal sheen of ice water. Scientists were stunned. Ice surface the size of the United States had disappeared. “This is unprecedented,” says Jay Zwally, a glaciologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. To have melt cover the whole of Greenland, he said, is “unknown.”11

A few days before the Great Melt, an iceberg the size of two Manhattans sheared off the Petermann Glacier and floated out to sea.12 The fraying edges of Greenland are slipping under water. For the first time in human history, blooms of algae sprout beneath the permafrost as sunlight filters through the blue melt caverns.13 Icy torrents roar down depthless, sapphire abysses called moulins, unmaking the ice sheets from below.

Panicked polar research teams crunched the numbers and agreed: polar ice melt had caused 20% of global sea level rise since 1992, and most of that melt was from Greenland.14 The Arctic ice domes had shrunk to their smallest size in recorded history, melting three times faster than anywhere else on earth, seven times faster than the 1990s. By century’s end, Glacier Park will have no glaciers; Iceland may well be named Icelessland, and the snows of Mount Kilimanjaro will be gone.

The ice sheets are our giant mirrors, reflecting the sun’s heat (in a process called albedo) and cooling the earth. As humans overheat the planet, the white ice melts faster. As it melts, it darkens, and absorbs more heat, and the great thaw speeds into a fateful, self-perpetuating spiral. As ice pours into the oceans, the oceans rise. And as the oceans warm, they expand and they rise. What filled scientists with dread in 2012 was not merely the immensity of the Great Melt, but that something unforeseen and catastrophic had been set in motion that could not now be stopped.

Formidably vast and far way, Greenland is the largest island in the world. The melting of Greenland has been called the greatest geological change to reshape the planet in human history.15 Ice sheets and glaciers also serve as the fragile, frigid retainers of the earth’s irreplaceable fresh water. Together with the Antarctic, Greenland’s ice sheets contain 99% of the fresh water on earth.16 Himalayan glaciers help regulate water to a quarter of humankind.17

But the Great Melt is abstract. Scientists tell us the Greenland ice sheet is 1,500 miles long, stretching the vertical length of the United States. They tell us the ice is two miles deep at the center. They tell us this massive ice cube contains a dizzying three quadrillion tons of solid water. That is 3,000,000,000,000,000 tons; a 3 with 15 zeros.18 And they estimate that when all that ice melts it will raise global sea levels by twenty-four feet, unleashing a planetary cataclysm that will drown the coastlines and mega-cities of human civilization that took millennia to make—undoing and reshaping the world.

But this is magical counting. The numbers speed across our eyes like a nightmare ticker tape: too fast to be imagined, too far away to feel tangible, conceivable, real. The problem is not precision. The problem is perception. Scientists tell us the ice sheets covering Greenland and Antarctica lose 344 billion tons of ice every year.19 But our imaginations strain against the numbers. We can’t see the scale and time of climate threat. The word “glacial” used to mean “slow.” Now “glacial” signals the speed and scale of climate catastrophe, moving at a magnitude our minds cannot picture. And if we can’t picture it, how can act to prevent it?

Our senses are tuned to the intimate signs of the years’ turnings, the green sunlight of spring, the soft sifting of snow, a hummingbird’s wing. We can see the fractal veins in a leaf and its twinned tracery in the palm of our hands, but we can’t see the bigger fractal of the Mississippi marshes slipping into a blue abyss every hour. Our tongues can’t taste the marshes turned to salt. Our fingertips can’t feel the warming oceans bleaching the coral reefs bone white.

Scientists tell us that 4.5 million square miles of Greenland melted, and to get the point across they tell us that Greenland is five times the size of California, or, if you prefer, three times the size of Texas.20 But if we can’t imagine the size of Texas, how can we imagine three times that much? Our minds are not suited for picturing the ice-caps melting, the tininess of nitrogen change, and billions of people learning to lead amphibious lives.

And because we can’t see, we have created satellites that see for us, traveling overhead at 17,000 miles an hour, their robot eyes opening and closing, recording the memory of the planet we are unmaking. And as the ice melts, the planet’s memory falters and is lost.

Elsewhere is here. The future is now. But the future has arrived at different times for different people. Forty-eight island nations are threatened by encroaching seas. The Maldives are drowning. Tuvalu and Kiribati are soon to go. Climate chaos, once seen as a far-away calamity comfortingly measured in centuries is now measured in decades, already endured by millions as the ordinary disasters of the everyday, whether in the blackwater slums of Lagos, the fluid streets of Jakarta, or the drowning of Louisiana.21

On what abacus can we count the slowly melting, the invisibly rising, but not yet drowned? We are like children counting on our fingers in the dark, trying to ward off the shapeless face of something dreadful that we have unleashed and that we cannot fully understand.

Myriad artists and activists across the world are reaching for new ways to express the inexpressible, make the invisible visible, the unthinkable tangible and real. In Paris in 2015, the artist Olafur Eliasson and geologist Minik Rosing brought twelve huge chunks of ice from Greenland and arranged the mini-icebergs in the Place du Pantheon in the shape of a clock. Participants at the United Nations Climate Change Conference could watch the Ice Watch melt, making visible our planet running out of time. Over thirteen million people have watched Ludovico Einaudi’s video Elegy For the Arctic, set in Norway’s Wahlenbergbreen glacier. The pianist sits at a black piano adrift in a chaos of melting ice; his plangent chords merging in fugue counterpoint with the clinking chords of fragmenting ice and the mewling of gulls, broken intermittently by the percussive roar of collapsing ice.

The problem of the Anthropocene is a problem of perception, but it is also a problem of the politics of denial, the administration of forgetting. The merchants of doubt—the alliance of global energy, chemical, big pharma and mega agri-corporations, the international arms trade and private surveillance contractors—collude with corporo-fascist governments, compliant corporate media, and lobbying groups like ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council) to thwart climate emergency policies through repressive legislation, criminalization, and assassinations.22

Now more than ever, we need to foster awareness of what the Pope in his encyclical Laudato Si’ calls “the plight of the poor and the plight of the earth.” In the 2012 documentary Chasing Ice, photographer James Balog installs twenty-seven time-lapse cameras at remote sites to film glaciers melting over time. His Extreme Ice Survey (EIS) serves as the digital memory-keeper of glaciers no longer there. The film records what the eye cannot see: time-lapse cameras fast-forward time, compressing years into seconds and offering a pyrotechnically gorgeous vision of the calamitous sublime. Now we need more creative strategies, stories, and images for making climate emergency real, visible, tangible. As Balog puts it: “Bear witness. Tell the story and give voice to the landscape. Sound the alarm.”

As my plane flies on, leaving Greenland and carbon trails behind us, spirals of ice spin across the sea like a galaxy of spilt stars.

Fugue III: Great Forgettings

Snowflakes fall to earth and leave a message.

—Henri Bader

Ice is time crystalized. Ice remembers. Ice is the custodian of deep time, sealing the past in its frozen crypts. The Artic’s white domes are the keepers of the earth’s memory. Far down in the Jules Verne depths of the permafrost, ancient air is trapped in tiny ice bubbles, the same air it was when the ice sealed it. Ice captures in its crystals a unique record of the earth’s climate history.23

In the 1950s, the science of glaciology emerged at the same time as the Cold War, and both converged in Greenland. In August 1949, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. The direct line of attack from the USSR to the US ran through the remote, ice-blind vastness of Greenland. In 1952, the US military unveiled Thule Air Base, built at frenetic pace and massive expense on the forbidding Greenland ice sheet. Named after the legendary Ultima Thule, Thule was vaunted an “engineering miracle… a guardian that looks steadily over the top of the world down into Russia.”24 Thule’s purpose was neither research nor exploration, but to “stake out a massive advantage in terms of bombs and planes, and to wrest victory in the coming Cold War.”25

138 miles away, swaddled in howling snow and frigid isolation, Thule had a spectral doppelganger. In 1960, the US built another military extravaganza, an army town called Camp Century, secretly hidden in a vast labyrinth constructed entirely under the snow. Camp Century was an improbable, icy catacomb of military hubris and western commodity culture, complete with church, hospital, store, barracks, officers’ club, theater, and a library containing 4,000 books. And to power all that comfort, there was the world’s first mobile nuclear reactor, costing $5.7 million.

The purpose of the Camp was as megalomaniacal as its construction. To control the Cold War, the US had to control the cold northern ice. To do so, it spawned a monstrous project called Ice Worm. The ambition of Ice Worm was to find out how to move six hundred intermediate ballistic missiles (IRBMs) secretly through a vast under-ice labyrinth of hundreds of miles of tracks and roads covering an area the size of Alabama. And then target the missiles at the USSR.

To keep the ambitions of Ice Worm secret, the military needed a cover. They claimed they were doing scientific research on ice. Not even the engineers knew why they were learning how to build hundreds of miles of tracks under the ice. And by unintended consequence, out of the icy catacomb of military vanity rose the visionary science of glaciology. Henri Bader, a pioneer cryologist at SIPRE, the US Army Core’s Snow, Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment at Wilmette, Illinois, was driven by an enchanting vision. He was sure that ice was a frozen archive of the deep past, whose secrets were encrypted in compacted snow. If made legible by science, ice could become a miraculous code for capturing not only the recent human past, but events before humans made records, before humans even existed at all.

Bader was right. Ice remembers. An ice crystal is akin to a frigid fragment of coded braille, making the deep past legible in tiny, tell-tale breaths of time. We can now look into deep time: reading telltale traces of the Industrial Revolution, the ash of ancient volcanoes, the signatures of tsunamis, past ice ages, meteor strikes. When crylogists drilled down to 1,000-year old ice, they dropped a fragment of the ice into a glass of Drambuie and called it Jesus Ice.26

In 2015, Camp Century surrendered to the gathering overburden of snow and the US military abandoned it, the site interred along with the immodest phantasms of Project Ice Worm. But ice remembers. With icy eyes, humans can now look into the frozen crypt of climates past. But we are now also obliged to look directly into the eyes of future monsters. One stares back at us from our icy future; certain knowledge that ancient climates had, and will now again, change not only gradually, but also catastrophically and unstoppably fast.

Fugue IV: Great Unburyings

Murdered, forgotten, nameless, terrible

Beheaded girl, outstaring axe

And beatification, outstaring

What had begun to feel like forever

—Seamus Heaney, “Strange Fruit”What we excrete comes back to consume us.

—Don DeLillo

As the world’s glaciers melt, things thought forever buried under the ice are rising to the sun. In 1991, hikers discovered Otzi, the Tyrolian Ice Man, cast up from his 5,300 year snowy slumber. In Norway in 2020, a melting mountain pass unburied ancient Viking artefacts perfectly preserved: shovels, distaffs, wooden keys, knitted mittens, a Bronze Age ski, arrows with feathers still attached, a horse’s snow-shoe.

Some artefacts are accidental augurs: the leathered bodies of human corpses that tell forgotten stories in cut throats and noosed necks. Some are intentional augerers, thinking in fugue time, passing messages of foreboding to future generations. When drought dried the river Elbe in 2019, it exposed carved “hunger stones,” small monuments both to the horrors of past droughts and warnings to future generations not to let the waters drop too low. One hunger stone speaks: “If you see me, weep.”27

In these unearthly stirrings, artefacts speak in fugue time. Thawing permafrost thrusts up the corpses of reindeer, also thrusting up spores of anthrax. Toxic methane rises from the warming boglands. We, the startled onlookers at a past thrust untimely into our present, find ourselves heirs to giant viruses and ancient parasites in mammoths and human corpses half-buried in melting permafrost, the future consequence of which we cannot fathom.

The retreat of Siachen Glacier, the highest military battleground on earth over which Indian and Pakistani troops have fought intermittently since 1984, enters the geography of haunted places. Warrened by military and industrial detritus, Siachen is a reliquary of war, artillery shells, ordinance, chemical blasting, and oil pipelines. Snowy crevasses dumped with waste and chemical toxins leach downstream into rivers below. Arundhati Roy calls Siachen the “most appropriate metaphor for the insanity of our times… A monument to human folly.”28 These great unearthings are visible reminders that our actions have epochal effects: that glacial revenants are revelations not only of the violence we inflict on each other, but of the violence we inflict on the planet.

And now as the ice sheets stir, Camp Century is shifting towards the light, bearing a monstrous legacy. The US military relied on the town being eternally sequestered in a sarcophagus of snow. The military also left behind a monstrous debris of war: much of the town itself, but most perilously 200,000 liters of diesel and unknown amounts of chemical, biological and radioactive waste. Under the administration of forgetting, Camp Century became a ghostscape, where forgetting is incomplete, returning to haunt the present.

Ghostscapes are damaged landscapes where traces of concealed violence nonetheless haunt the margins of the visible. They appear as haunted geographies and accusatory apparitions on the landscape itself: the bone lands of famine and genocide; half-buried munitions; eerie ecologies such as ghost forests and skeleton trees; abandoned wastelands or military borderlands. Take the flinty ghosts of the Irish famine roads dug by starving wraiths in the nineteenth century. Or the atomic shadows blasted onto stone in Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the nuclear weapons of monstrous light. Or the crimson black smears of oil mixed with Corexit that stretched to every horizon during the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Fugue V: The Administration of Forgetting

Foule monster monger, who must live by that

Which is thy owne destruction.

—T.D Bloodie Banquet 11.ii 1639“How did people not know it had happened?”

“But we all knew,” said the Native child.

On April 20, 2010, the BP Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Macondo Prospect; a crimson and gray apocalypse pitching and sinking, taking with it eleven men dead. The disaster unleashed more than ten million gallons of oil across the Gulf of Mexico, becoming the largest environmental disaster in US history.29 It also became the largest cover-up of an environmental disaster in US history.

The forever war had come ashore and the Gulf became a ghostscape. A calamity of untold magnitude unfolded and alongside it a strange militarization emerged, as the language for managing the crisis became the language of war. War talk fired from the media, the Coastguard, and local officials alike. State Governor Bobby Jindal: “We need to see this is a war. A war to save Louisiana.” Billy Nungesser, President of the Plaquemines Parish: “We will persevere to win this war.” Political consultant James Carville: “This is literally a war.” And General Russel L. Honoré: “We need to act like this is World War III. Treat this like it’s an invasion. We’ve got to find the oil and kill it.”

Visit the BP website in 2010 and you would see the word “kill” appear with ritualistic incantation.30 Kill the well. Kill the leak. Kill the oil. Culminating in the “kill shot,” the weird slurry of car tires and golf-balls that BP initially fired at the leak to “kill” it. As if by throwing the sacrificial detritus of our oil-soaked leisure activities into the maw of the oil-god, BP could stop it spewing death.

This was truly strange talk, this talk of war and killing oil. Only a tremendous failure of the imagination could see it as a war. But since the 1970s, almost every crisis of neoliberalism has been called a war: the war on drugs, the war on crime, the war on poverty, the war on AIDS, the war on terror, and now the war on oil.

All this talk of war ghosts the fact that militarization is the largest single cause of environmental destruction in the world. The US military is the largest single polluter on the planet.31 The Department of Defense is the largest single consumer of oil in the world. And the Pentagon is BP’s largest client.32 But the hinge that connects the environmental catastrophe of militarization and the militarization of environmental catastrophe has been ghosted. With the conjoined collusion of BP, the US Coastguard, the National Guard, and the Obama Administration, the Gulf disaster fell into a great, administered forgetting.

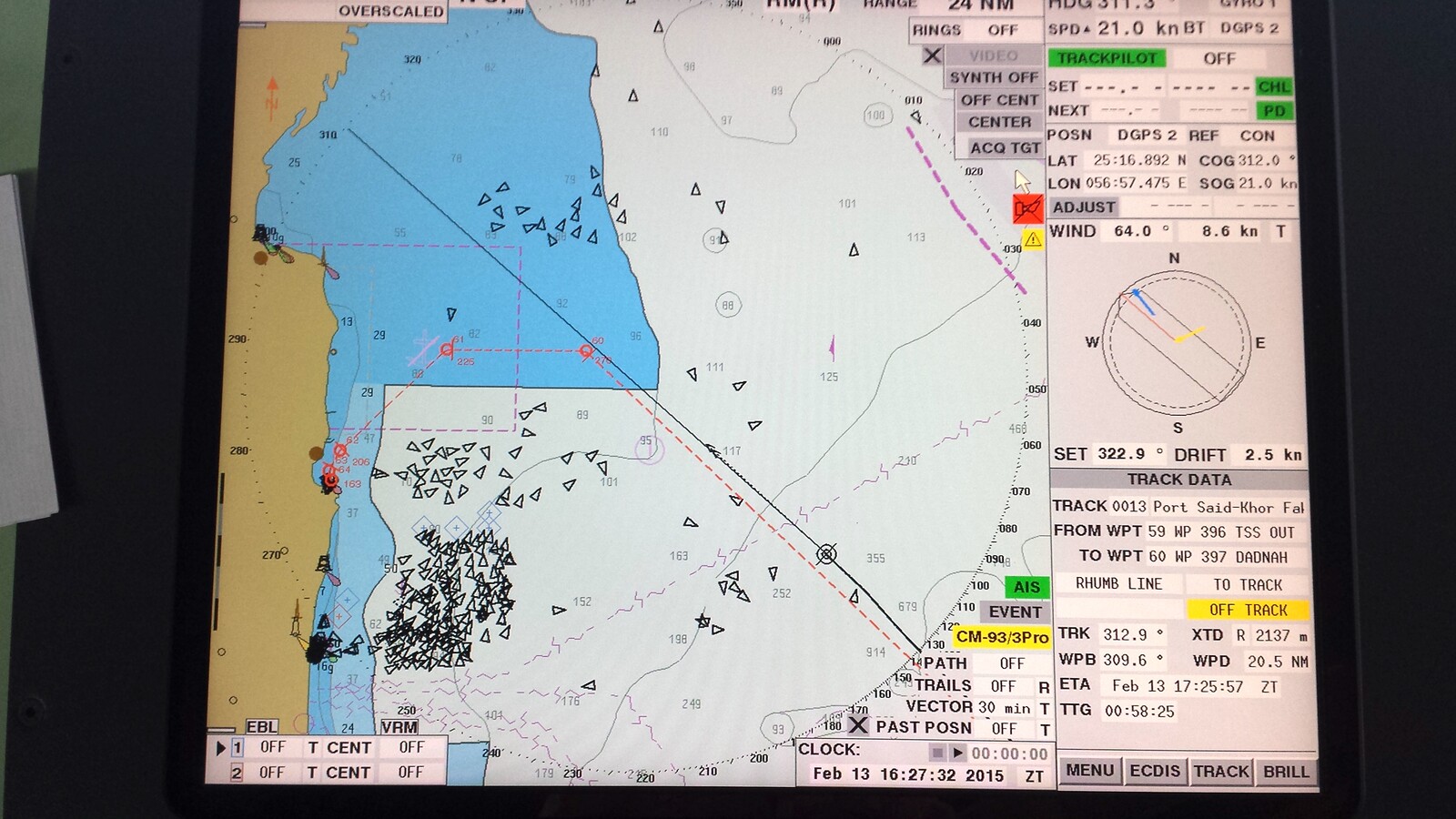

Shortly after the blowout in June, an extraordinary ruling was passed. No one could go within sixty feet of oil-damaged areas effective across five states. No one could go within sixty feet of barrier islands, oiled marshes, birds, boom, public beaches, clean-up boats, or clinics, and independent fly-overs were forbidden. BP workers were forbidden to talk to any media. Scientists had to sign non-disclosure agreements. And if anyone violated the ruling, they faced $40,000 fines or felony charges.33 To get behind the blockade, I hired a tiny Cessna plane and took to the illegal skies.

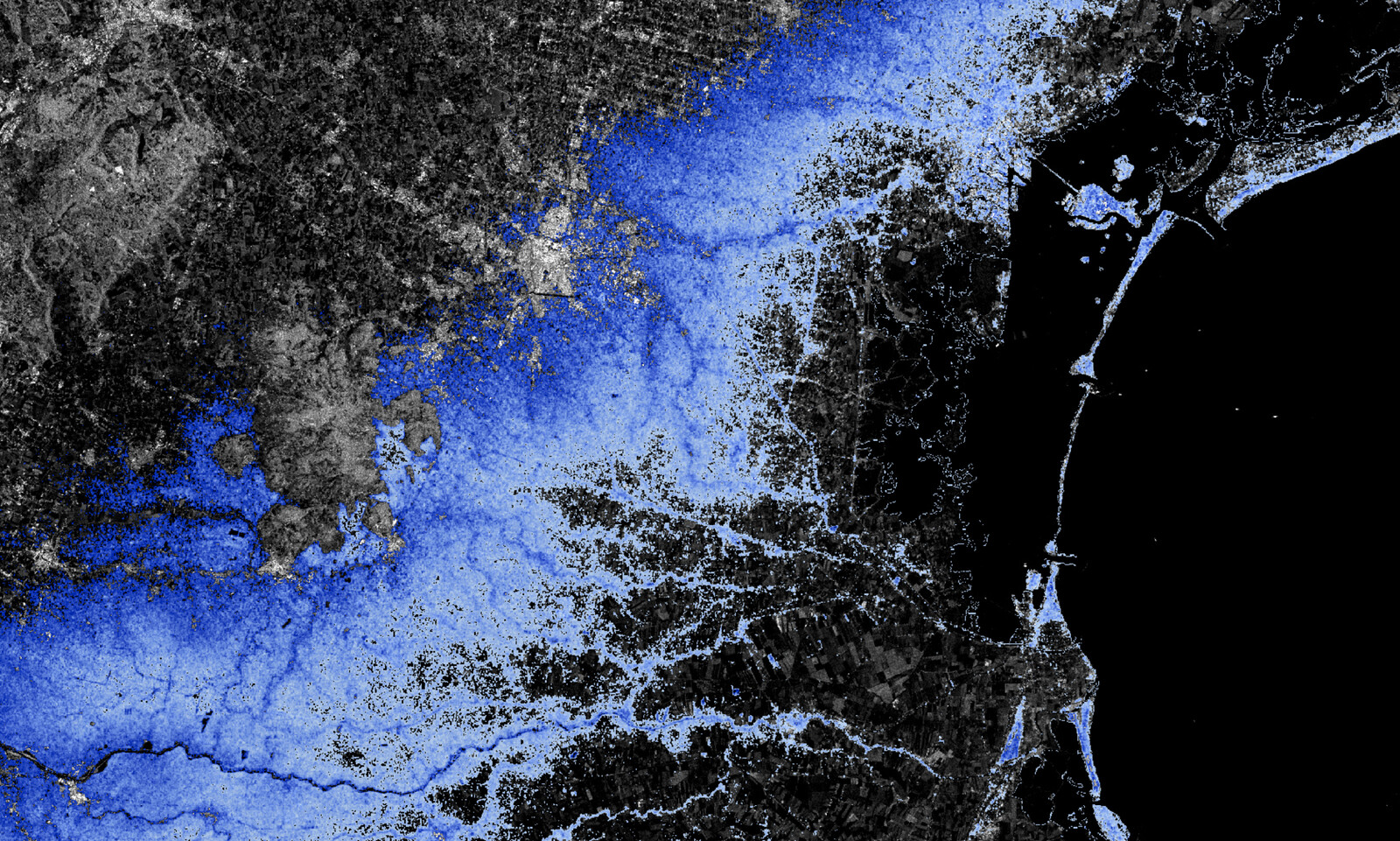

I am flying, I see smears of pink oil stretching for miles: telltale signs that the Gulf is being sprayed by massive amounts of the toxic chemical Corexit. Why? BP had agreed to pay damages for “verifiable evidence.” To hide the evidence, military planes “carpet-bombed” five Gulf states with still untold amounts of Corexit. But Corexit doesn’t remove oil, it just sinks it out of sight. Corexit became a conjuring trick; a sorcerer’s bargain with life and death. But the administration of forgetting leaves traces of what it tries to forget: when sprayed on oil, Corexit turns an eerie pink. Corexit’s alchemy of erasure paradoxically revealed the cover-up in the very act of trying to conceal it.

Since the disaster, people in the Gulf have become very sick. 400 new species are endangered, monstrous deformities are appearing in marine life, vast plumes of oil stretch for miles on the ocean floor, mangrove barrier islands are dying, and a dead zone—officially called the “kill zone”—stretches for hundreds of miles.34 Reports in 2020 reveal the effects of the BP oil disaster are ongoing and 30% larger than originally calculated.35

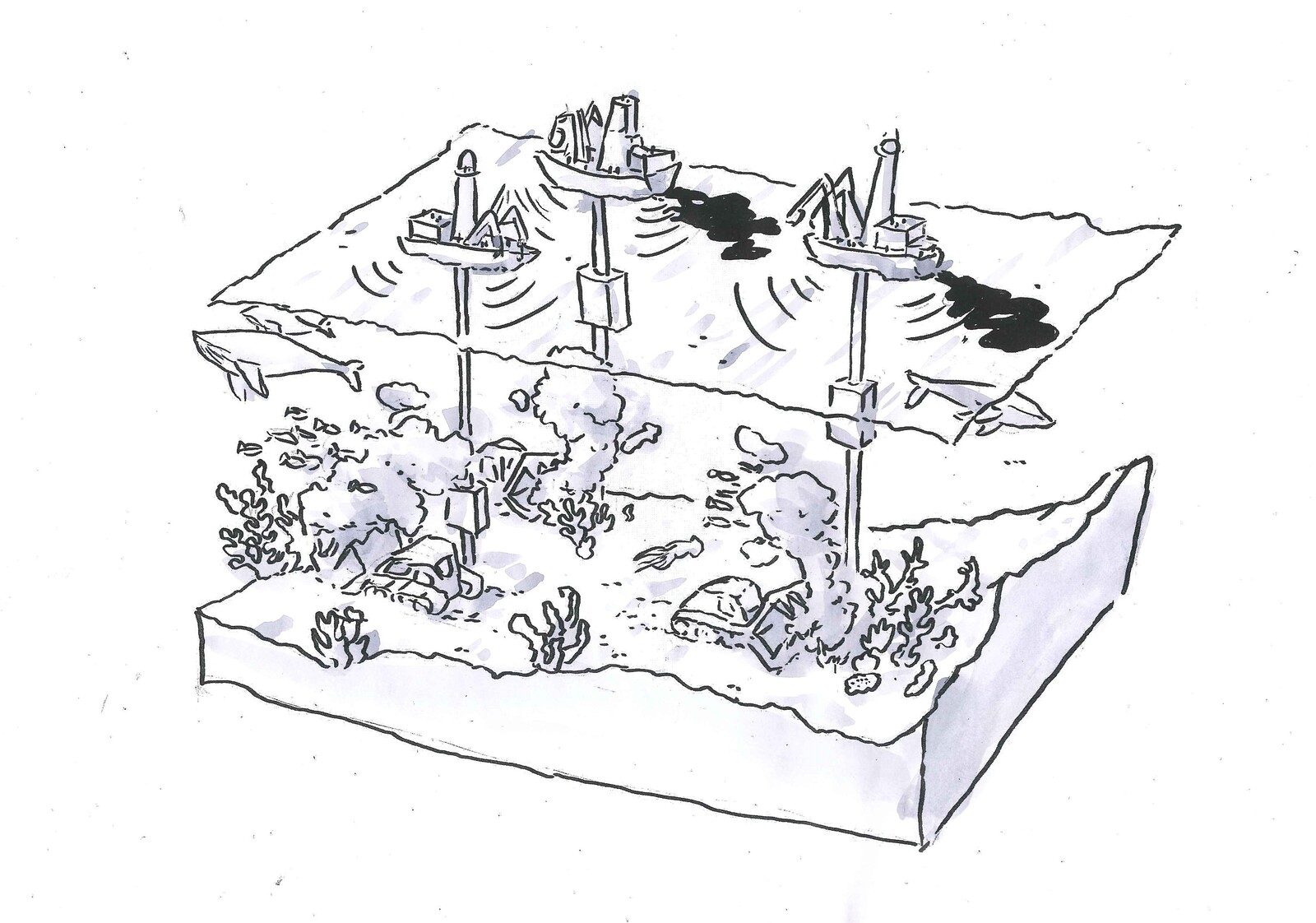

What many don’t know, is that the militarization of the Gulf catastrophe was also a soft launch of what the Pentagon calls “a revolution in warfare”: using climate emergency to justify perpetual war. Climate change has become the Pentagon’s new, improved “hostile.”36 The US military has long been aware of climate change. Climate chaos is now seen as both a threat multiplier and a huge opportunity for the military. Admiral Thomas J. Lopez puts it bluntly: “Climate change will provide the conditions that will extend the war on terror.”37 Climate disaster is a new paradigm for suppressing media coverage of war, for new Special Ops and Dark programs, for legitimizing assassinations and drone warfare, and for criminalizing environmental activism, as climate justice activists are put on “terrorist lists” and some levied severe prison sentences. National security becomes natural security as climate chaos serves as an alibi for global military intrusion. The planet now offers myriad “Ground Zeros” for military intervention—from Ferguson to Standing Rock, from the South China Sea to the Arctic Circle.

And down in Barataria Bay, the crabs climb out of the burning water and hold their claws to the sky. Boats are still. Sails are shrouds. Children cough the BP cough.

Fugue VI: Fire and Ice

It is 2019. I am flying over Greenland again. Far below me a glacier thin and wrinkled as old skin, a black rock bare of snow, looks up with a reptilian eye of emerald melt pools.

The Great Melt of 2012 was not supposed to recur for another seventy-five years, but it happened seven years later. 2019 became the OMG year of climate emergency. OMG is the (intentionally alarmist) acronym for NASA’s “Oceans Melting Greenland” project. Scientists understood how the ice was melting, but their predictions of the 2012 Great Melt were wildly off. Something was missing. Why was ice melting so fast?

A young climatologist named Jason Box, who predicted the Great Melt of 2012 a few weeks before it happened, offered a plausible provocation.38 What if the extreme ice melt of 2012 was amplified by the convergence of increasing soot from global wildfires? What if rampant global wildfires, added to coal plant smoke in China, had darkened the Arctic snow and amplified the Great Melt?

2019 was another year of record-breaking climatic upheaval. Fatal heatwaves struck Europe and India; wildfires incinerated Australia’s coasts, emptying birds out of the sky and koalas out of trees. The Arctic was engulfed in an “extreme melt event” more severe than 2012. “It’s just crazy, crazy stuff,” says Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. “These heat waves—I’ve never seen anything like this.”39

Small acts have epochal effects. A spark. In 2019, pine trees in the Rockies are tinder dry, undone by record heat and insect infestations. A hiker tosses a careless match. A monumental wildfire. Smoke wafts into the jet-stream, floats over Greenland and settles on darkening ice, which melts out of the glaciers into the oceans, which invisibly rise, seeping into the Sunderbans, the blackwater slums in Makoko Lagos, and the marshes of southern Louisiana, where Hurricane Barry nearly drowns Isle de Jean Charles under a fifteen foot storm surge.

Scientists now predict that 300 million people will face chronic flooding not by century’s end, but during the next thirty years.40 Sea level rise is global, but the countries with the most amount of people affected are in Asia: China (67 million), Bangladesh (37 million), India (31 million), Vietnam (22 million), Indonesia (18 million), and Thailand (11 million), including mega-cities like Shanghai (24.3 million), Kolkata (14.9 million), Dhaka (8.9 million), and Bangkok (8.2 million). Mumbai (18.4 million), India’s financial capital, will likely be wiped out. And Jakarta (9.6 million). Southern Vietnam could all but disappear.41 The mind baulks at such a scenario; too grotesque, too apocalyptic, too freighted with suffering and mega-death to be conceivable.

In The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh makes a prescient point: for most of human history people were wary of coastlands.42 In the seventeenth century, colonial empires unleashed what Ghosh calls “the great derangement”: an estrangement from environments and a colonial complacency that was “itself a kind of madness.”43 Satisfying maritime colonial needs to be close to coastlines, future mega-cities like Mumbai (Bombay), Chennai (Madras), New York, Boston, New Orleans, and Miami were built on fluid lands, marshlands, and deltas; a foundational imperial folly now laid bare as catastrophic. These colonial cities and surrounding lands will be the first to face the oncoming deluge. The brunt of the Anthropocene falls most heavily on the global poor.

A fugue in fire and ice.

Fugue VII: Atlas of a Drowning World

This is the map of the forsaken world

This is the world without end

Where the forests have been cut away from the trees

These are the lines wolf could not pass over.

—Linda Hogan (Chicksaw), “Map”

Louisiana is the fastest disappearing land on earth.44 The verdant coastlands and marshes teem with fish, but every hundred minutes, land the size of a football field vanishes under water.45 The ragged sole of the Louisiana boot is nearly gone.

Deep in the fragile southern marshes, the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe cling to a vanishing shard of land. Once the size of Manhattan, the island has frayed into a fragment two miles long and a quarter of a mile wide. With the next big hurricane, residents tell me, the island could go, its name washed from the map forever.

I am flying. At my side, the island seems to be flying too; a half-hallucinatory bird, its eyes pointing to the far horizon. But one wing seems caught in melt from the faraway ice caps. The island bird breathes water.

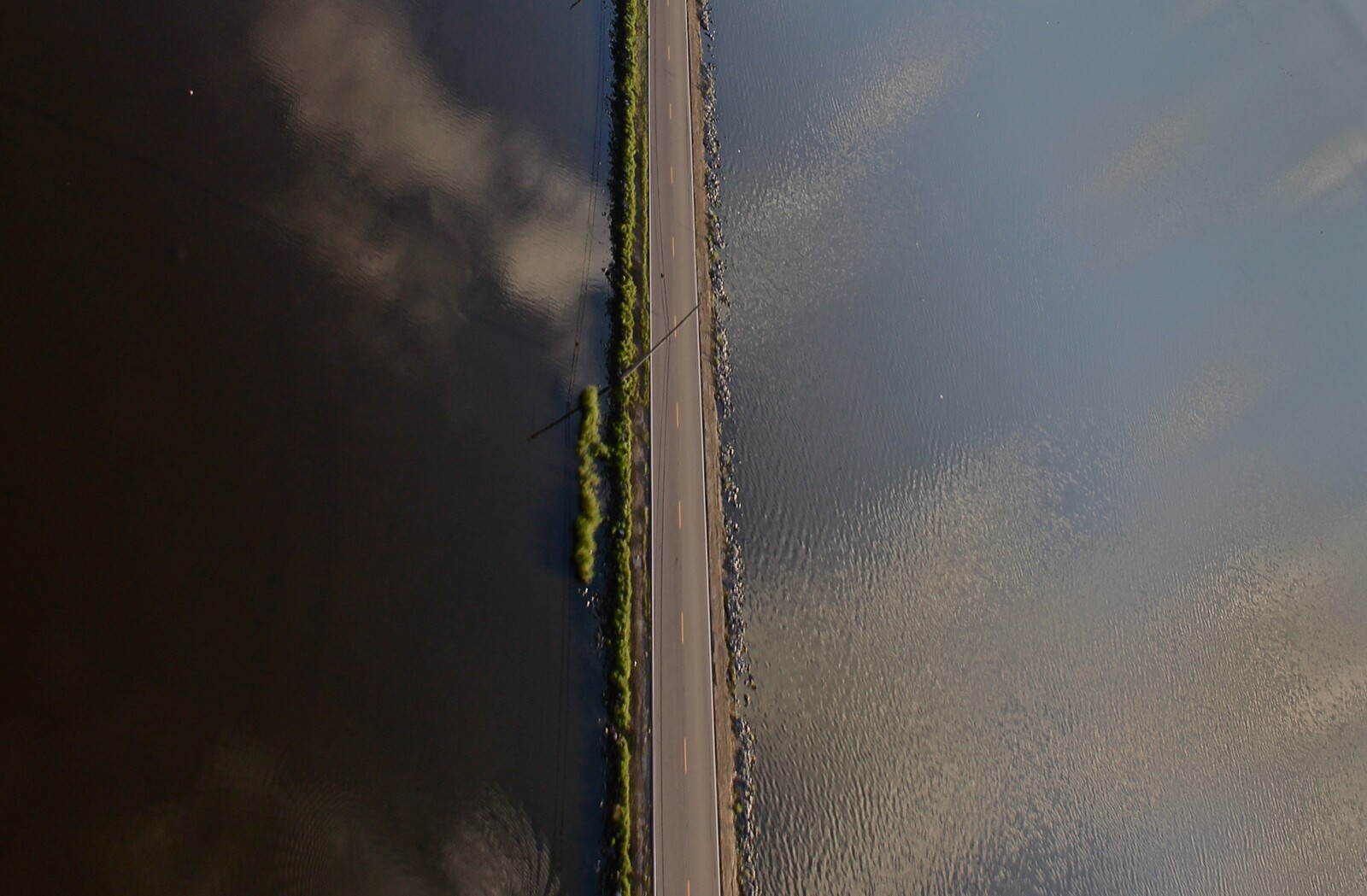

A single road tethers the island to the world, so thin and broken that when great storms surge, the road drowns under water, sometimes leaving the people marooned for years.

The inhabitants of Isle de Jean Charles, mostly Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, have been called the first federally funded “climate refugees” in the US.46 In 2016 , the State of Louisiana won a $48 million federal grant to relocate them to a suburban settlement further inland, and the media of world is waiting to see how they do it.47 But in talking to Chief Albert Naquin (Choctaw), Chris and Juliette Brunet (Choctaw), and other tribal members on the island, I found a more troubling story. The islanders are caught in a paradox: not only between rising waters and wanting to stay on their island, but also between being hailed as climate refugees while not being federally recognized as existing in the first place.48 Their proposed settlement is a sugar cane farm—a ghost of the colonial system that ravaged Native cultures in the first place.49 Colonial déjà vu.

The islanders’ Choctaw forebears fled the brutal land theft of the 1830 Indian Removal Act, a colonial cataclysm during which thousands of Native people were driven off their lands east of the Mississippi to territories in the west. The Trail of Tears that followed enacted a double violence, both against Native people as well as enslaved Africans, as Native lands were emptied to make way for sugar and cotton plantations.50

Some Choctaw, like the Brunet’s ancestors, fled the great removals and found refuge in marshes so abundant they sustained themselves—alongside Chitimacha, Biloxi and Houma—in peaceful solitude for nearly a century.51 Hundreds of people lived on the vast green island in log and clay houses. The gardens lush with watermelons, cantaloupe, and cucumbers; the fruit trees hung with figs, peaches, and persimmons. Chickens and pigs wandered the gardens. Fat cattle grazed the waterlands. Meadows of marigold and matrimony vine, the spring marshes loud with blue-winged teal and snow geese, the bayous teeming with shrimp and oysters, beavers and muskrat. All of it now gone. Chris Brunet’s grandmother, Regina, showed him where herbs used to grow. All that is left are their names, and the names are now vanishing too.52

Then in the 1920s, the oil companies came.

Now the islanders are being driven from their homes by the same economic rapacity that drove their ancestors off their lands. Companies drilling for oil have sliced the vast wetlands into ribbons. Rigs suck oil out the marshes and the marshes sink. Canals draw salt water into the wetlands and the vast forests die, bleached into skeletal ghost trees. Rising waters are floating the island away.

As the waters rise, the houses rise too, floating some fifteen feet high. The water-people are learning to lead sky-borne lives.

Some Islanders refuse to leave. They are holding on with their fingers to the frail scaffolding of their lives. They are holding on to torn time, before the high water comes, their demon-lover, to float everything away in its arms. They are turning their backs on the howling havoc of the hurricanes, on the politicians and the media, on the water pouring in through the final hourglass of their days. But the waters rise, seeping under doors, filling tea cups, soaking mattresses, and floating children away.

On Island Road, I come to a blue house. Three children are climbing a blue wall of water. At the top of the waterslide, a white plastic wave curls over them; a frozen wave of ice, permanently threatening to fall. The children live among ghosts, in a world made and unmade by oil. The plastic cups and hose pipes are made from oil. Oil is the monster we cannot see. Small boy, so thoughtful, are you practicing in play to climb the wave looming over your house, on the other side of the marshes, on the other side of childhood?

The islanders laugh. But when they talk of an island leafy and luxuriant, their voices become waterlogged and submerged. Shrimp fisherman, Russell Dardar (Point aux Chiene Indian) took me out on his shrimp boat to see the skeletal after-life of the drowned forests; a broken, watery emptiness where as a child he rode horses through verdant forests.

I am flying again. Below me, the vast wetlands have been sliced and diced into a ruined ghostscape. The islanders call the once lush forests “skeleton” or “ghost trees.” Every straight line made by the oil companies is a fatal artery pulling salt water into the marshes. The body of the land is hurt. Ragged strips of the marshland float away like green scabs. The sea is a sea of dementia. Drowned beneath the water lie houses, farms, horses, and sacred burial grounds. The last tree on Island Road leads arthritically against the evening sky.

At the end of the island, a statue to Christ holds out his arms. He is called Man of Sorrows. Ahead, a red light gleams. Islanders are refusing the storm. Their bodies gleam like fish; they are fish-men, breathers of water. They are dancing an ancient, slow dance. They are learning to lead amphibious lives, casting their nets of hope.

In losing Isle de Jean Charles, the world is not just losing an island with an irreplaceable community. A lifeway is being lost. An Indigenous ethic of intimate relations between people and land. An ethic of being beholden—of holding others and knowing one will, in turn, be held.

Men fishing through a storm on Island Road, Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Photo: Anne McClintock, June 7, 2016.

Fugue VIII: Demonstration

As oceans rise, so do activists for climate justice, led in many countries by Indigenous people. A year after the BP disaster in the Gulf, a newly galvanized environmental justice movement emerged in the United States to protect Native lands and waters. In early 2017, the peaceful Standing Rock protests against the Keystone Pipeline were brutally dismantled by militarized police.53 A few weeks later, an oil pipeline was slated to cross tribal land in Oklahoma.54 Oklahoma has thirty-nine Native Nations, most of whom were forcibly moved there during the Trail of Tears. A coalition to protest the pipeline quickly emerged. The following week, Bill 1123 was introduced in the Oklahoma State Senate. The Critical Infrastructure Protection Act “would impose punishments of up to 10 years in prison and $100,000 in fines—and up to $1 million in penalties for any organization ‘found to be a conspirator’ in violating the new law.”55 Defined by the bill, “critical infrastructure” broadly refers to oil, gas, chemical, or coal equipment or facilities, and violation is any act deemed willful “trespass” on facilities or land. Even stepping on a pipeline easement can incur a year in prison.

The Critical Infrastructure Protection Act soon became the blueprint for a raft of radically repressive bills that have since been quietly introduced in thirty-one states across the country. In 2020, during the Covid-19 lockdown, further bills were introduced in four new states.56 The bills, drafted by the shadowy group ALEC, effectively criminalize peaceful protests, activists, and organizations.57 A projected bill in Alabama would levy severe penalties against environmentalists using unmanned drones to track pollution.58 More ominously, a Pennsylvania bill would criminalize peaceful protests as “demonstrations,” so broadly defined as to include “expressive activity or the communication or expression of views or grievances, which has the effect, intent, or propensity to draw a crowd or onlookers.”59 Protestors are now being cast as economic “terrorists” and dubbed the “top domestic terrorist threat” to pipelines.60 Arrests are already being made.61

As repressive legislation within the US offers a right-wing demonstration of legislative violence, the northern permafrost thaws, and the US military offers a global military demonstration in the melting of the Arctic ice. The United States, Russia, Canada, and Denmark are racing towards a massive monster of oil and mineral wealth rising out the melting ice. Until they were suddenly cancelled in March 2020 due to the pandemic, mock war games called Cold Response joined thousands of American combat troops with thousands of NATO soldiers in Norway. The simulated engagement pitches allied forces against imagined invading forces from Russia; a multinational joint exercise in demanding winter conditions. There is nothing ordinary about Cold Response. As military historian Michael Klare warns: “It’s being staged above the Arctic Circle … and raises to a new level the possibility of a great-power conflict that might end in a nuclear exchange and mutual annihilation. Welcome, in other words, to World War III’s newest battlefield.”

A demonstration. An ancient military term for a show of armed force. Will we heed its warning?

Coda: Monument

Human rights, social justice and gender equality are all intrinsically connected to the fight because climate justice affects the poor more than the rich, the underprivileged more than the privileged, and women differently than men.

—Katrin Jakobsdottir, Prime Minister of Iceland

In 2014, the Okjökull glacier was officially pronounced dead.62 In the late summer of 2019, a funeral procession was held for Ok, and a monument called “A Letter to the Future” was unveiled to mark the frozen body of the glacier with a plaque, as both a warning and a mourning.

OK is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. The monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you will know if we did it.

Fugue time disrupts Enlightenment time. Enlightenment time is clock time and calendar time; time chained to a pocket-watch, schedules and school bells, doing prison time, clock-in time, check-out time. The Anthropocene invites an affinity with fugue futures, refusing the grand linear narratives of Enlightenment modernity disguised as progressive time. Thinking through fugue futures invites a radical perspective of collective time, multi-vocal and dissonant, conjoining beauty and trouble in contrapuntal complexity. New responsibilities open. Fugue futures open to an assemblage of entanglements of which humans are only one filament.

We must keep faith in fugue futures, so the past does not continue to wound the present. To read ghost ecologies only for their dark histories is another violence, disallowing the possibilities of resurgent life and generous beauty.

Fugue time is aligned with tidal time, moon time and almanacs, the seasonal looping of swallows. Fugue futures are aligned with earth’s animacy. Given time, rocks travel, glaciers speak volumes, marshes migrate, forests commune in subterranean fungal whispers. As the Corona pandemic of 2020 curtailed human activity, forms of resurgent life leapt to view. The horizons of Delhi turned sky blue again; peacocks pranced down highways; elephants reclaimed the streets. Penguins strutted through Cape Town. We must remember these intimations of abundant life. As Arundhati Roy writes:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.”63

We have the ethical obligation to embrace these offerings of nature’s emergence. We must remember these flashes of emergent beauty, not as encounters that deny affliction, but as the collective imaginary of fugue futures where profound suffering is entwined with improbable beauty and the enchantment of the ordinary.

“We know what is happening. We know what needs to be done.” I have come to believe that if we begin with what we love, we give mourning and grief its fullness. Grief makes us kin with what we mourn, and out of that kinship, radical transformation will more likely rise up. Protecting what Rachel Carson called “the precious web of life” is within our reach. Not just for ourselves, but for the strangers who walk the future planet in our footsteps. No act is too small to make a difference. The future is now.

We must learn to speak with ghosts, for specters disturb the administration of forgetting, and the hauntings of popular memory will return to challenge the great forgettings of official history. As Eduardo Galeano writes: “History never really says goodbye. History says: See you later.”64

Ben Hubbard, “Money flows with refugees, and life jackets fill the shops,” New York Times, September 26, 2015, ➝.

I explore what I call phantomogenic readings of photographs and landscapes in my essay “Ghostscapes from the Forever War,” in Nature’s Nation. American Art and Environment, eds. Karl Kusserow and Alan Braddock (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 272–288. I am indebted to Avery Gordon, Toni Morrison, Saidiya Hartman, Jenny Sharpe, Marianne Hirsch, Gabriele Schwab, Russ Castronovo, and Renee Bergland for their explorations of ghostly matters.

Hubbard, ➝.

Arundhati Roy, Capitalism. A Ghost Story (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014), 7.

It is now generally agreed that in 2011, at the border city of Daraa, farmers were driven in desperation by a series of droughts to ignite the protests that marked the beginning of the Syrian civil war. Syria now has eight million displaced people. What is ghosted from much of the media is that the second largest foreign contingent fighting in support of Syria’s Al-Assad are Afghan refugees from the failed US war of occupation.

On militarization and environmental crises, see Jacob Darwin Hamblin, Arming Mother Nature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Robert Marzec, Militarizing the Environment. Climate Change and the Secuiry State (Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2013); Christian Parenti Tropic of Chaos (New York: The Nation, 2013); Winona LaDuke, The Militarization of Indian Country (East Lansing: Makwa Enewed, 2013).

Norwegian Refugee Council, ➝. For an extended account of forced displacements worldwide, see Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2018, a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. ➝. Peter Beaumont, “Record 68.5 million people fleeing war or persecution worldwide,” The Guardian, June 19, 2018, ➝.

UNHCR, ➝.

Suzanne Goldenberg, “Greenland ice sheet melted at unprecedented rate during July,” The Guardian, July 24, 2012, ➝

Suzanne Goldenberg, “Artic lost record snow and ice last year as data shows changing climate,” The Guardian, December 5, 2012, ➝.

Goldenberg, “Greenland ice sheet,” ➝.

“Iceberg breaks off from Greenland’s Petermann Glacier,” BBC, July 19, 2012, ➝.

Goldenberg, “Artic lost record snow and ice,” ➝.

Christine Dell’Amore, “Polar Ice Sheets Shrinking Worldwide, Study Confirms” National Geographic, November 30, 2012, ➝

David Shukman, “Climate Change: Greenland’s Ice faces Melting Death Sentence,” BBC, September 3, 2019, ➝.

“Ice Sheet,” National Geographic, ➝.

Katrin Jakobsdottir “Iceland’s Prime Minister: ‘The Ice is Leaving,’” New York Times, August 17, 2019, ➝.

Jon Gertner, The Ice at the End of the World (New York: Random House, 2019), xiv. I am indebted to Gertner’s magisterial book.

Joseph Stromberg, “Confirmed: Both Antarctica and Greenland Are Losing Ice,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 29, 2012, ➝.

Gertner, xvii.

See Ashley Dawson, Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (New York: Verso, 2017; Jeff Goodell, The Water Will Come (New York: Little, Brown and Co, 2017); Mike Tidewell, Bayou Farewell: The Rich Life and Tragic Death of Louisiana’s Cajun Coast (Knopf Doubleday, 2007).

See Naomi Oreskes and Erik. M Conway, Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010). ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, is “one of the most powerful, secretive organizations in the United States. Heavily funded by the Koch and Sarah Scaife Foundations, ALEC operates by wining and dining corporate leaders and legislators behind closed doors to produce ‘model’ blueprint bills, which state legislators introduce in their states without ALEC’s visible imprimatur.” Anne McClintock, “Who’s Afraid of Title IX,” Jacobin Magazine, February 23, 2017, ➝.

Gertner, chapters 11 and 12.

“The name, pronounced TOO-lee, derived from the 330B.C voyage of Pytheas, who had sailed north from Greece and reached the pack ice and glimpsed land, the land of the furthest north, that he called Ultima Thule.” Gertner p. 159. And “In classical and medieval literature, ultima Thule (Latin “farthermost Thule”) acquired a metaphorical meaning of any distant place located beyond the ‘borders of the known world,’” ➝.

Gertner, 163. Thule Air Base became a small city that could house ten thousand personnel, sporting an airstrip, barracks, post office, baseball diamond, gymnasium, and churches. The reasons for Thule were, nominally, access to the rare mineral cryolite, potential for weather predictions and a strategic stopover. But as Gertner points out, Thule had nothing to do with science or exploration.

Gertner, 201.

Robert Macfarlane, Underland: A Deep Time Journey, (New York; Norton, 2019) 14.

Macfarlane, 329. Arundhati Roy, “What Have We Done to Democracy?,” Guernica, September 28, 2009, ➝.

One of the most authoritative accounts of the disaster is Peter Lehner with Bob Deans, In Deep Water. The Anatomy of a Disaster, the Fate of the Gulf, and how to End our Oil Addiction (New York: Or Books, 2010)

“bp.com,” Wayback Machine, August 12, 2010, ➝.

See Anne McClintock “Slow Violence and the BP Oil Crisis in the Gulf of Mexico: Militarizing Environmental Catastrophe,” 9.1–9.2 On the Subject of the Archives 9, no. 1 and 2, 2012, ➝.

Scientific studies establish that the BP catastrophe has altered the very structure of molecules around the Macondo site. Oliver Milman, “Deepwater Horizon Disaster Altered the Building Blocks of Ocean Life,” June 28, 2018, ➝; Huan Chen, “4 Years after the Deepwater Horizon Spill: Molecular Transformation of Macondo Well Oil in Louisiana Salt Marsh Sediments Revealed by FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry,” Environmental Science and Technology 50, no. 17 (2016): 9061–9069; Oliver Millman, “I Pray to God It Never Happens Again,” The Guardian, April18, 2020, ➝; Emily Holden, “‘Of course it could happen again’: experts say little has changed since Deepwater Horizon,” The Guardian, April 20, 2020, ➝.

Edward Helmore, “Deepwater Horizon Disaster Had Much Worse Impact Than Believed, The Guardian, February 13, 2020, ➝.

One cannot overstate how pervasively the trope of “Indian Country” has been used by the United States military to characterize as yet unsubjugated territories in active war zones around the world. Throughout US history, to be “in Indian Country” was to be behind enemy lines, from the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, and beyond. See McClintock, “Ghostscapes from the Forever War,” 281–282.

The CNA Corporation, National Security and the Threat of Climate Change (Alexandria, VA: CNA Corporation), 17, ➝.

Goodell, The Water Will Come, 49–73.

Associated Press, “Artic has warmest winter on record: ‘It’s just crazy, crazy stuff,’” The Guardian, March 6, 2018, ➝.

“Report: Flooded Future: Global Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise Worse Than Previously Understood,” Climate Central, October 29, 2019, ➝. Added to which, in “19 countries, from Nigeria and Brazil to Egypt and the United Kingdom, land now home to at least one million people could fall permanently below the high tide line at the end of the century and become permanently inundated, in the absence of coastal defenses.”

Denise Lu and Christopher Flavelle, “Rising Seas Will Erase More Cities by 2050,” New York Times, October 19, 2019, ➝.

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement. Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 2016), 37.

ibid, 35.

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Louisiana’s Disappearing Coast,” The New Yorker, April 1, 2019.

“USGS: Louisiana’s Rate of Coastal Wetland Loss Continues to Slow,” USGS, July 12, 2017, ➝.

Carolyn van Houten, “The First Official Climate Refugees in the U.S. Race Against Time” National Geographic, May 25, 2016, ➝.

Coral Davenport and Campbell Robertson, “Resettling the First American Climate Refugees,” The New York Times, 2May 2, 2016, ➝.

Julie Dermansky, “Louisiana and Isle de Jean Charles Tribe Seek to Resolve Differing Visions for Resettling ‘Climate Refugees,’” Desmogblog, February 5, 2019, ➝.

Tristan Baurick, “Retreating from rising sea, state completes purchase of Isle de Jean Charles relocation site,” The Times-Picayune, January 9, 2019, ➝.

Jamila Osman, “Colonialism, Explained,” Teen Vogue, November 22, 2017, ➝.

Anne McClintock,”The Last Teenagers on Isle de Jean Charles, An Island Climate Change Is Washing Away,” Teen Vogue, 12 February 2020. ➝.

On the #NoDAPL movement see Kyle Powys Whyte (Potawatomi), “The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice and US Colonialism,” Red Ink 19, no.1 (Spring 2017): 154–169; Nick Estes (Lower Brule Sioux), Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (New York: Verso, 2019.

Lee Fang, “Oil Lobbyist Touts Success in Effort to Criminalize Pipeline Protests,” The Intercept, August 19, 2019, ➝.

Nicolas Kusnetz, “How Energy Companies and Allies are Turning the Law Against Protestors” Inside Climate News, August 22, 2018, ➝.

Alexander Kaufman “Yet Another State Quietly Moves To Criminalize Fossil Fuel Protests Amid Coronavirus,” Huffington Post, August 5, 2020, ➝.

“Critical Infrastructure Protection Act,” ALEC, January 20, 2018, ➝.

Hillary Simon, “Alabama Environmental Group concerned over proposed drone bill,” CBS 42, March 9, 2020, ➝.

“Senate Bill no. 323,” The General Assembly of Pennsylvania, February 22, 2019, ➝.

Susie Cagle, “Protestors as Terrorists,” ➝.

Laura M. Holson, “Iceland Mourns Loss of a Glacier by Posting a Warning About Climate Change, New York Times, August 19, 2019, ➝.

Arundhati Roy, “The pandemic is a portal,” Financial Times, April 3, 2020, ➝.

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997), 52.

Oceans in Transformation is a collaboration between TBA21–Academy and e-flux Architecture within the context of the eponymous exhibition at Ocean Space in Venice by Territorial Agency and its manifestation on Ocean Archive.

Category

Subject

Oceans in Transformation is a collaboration between TBA21–Academy and e-flux Architecture within the context of the eponymous exhibition at Ocean Space in Venice by Territorial Agency and its manifestation on Ocean Archive.