It feels like only yesterday that a cat was a cat and a computer was a computer. But today, instead of tidy distinctions, humans, animals, and machines—and multitudes of others—jostle uneasily on a blurred gradient of consciousness, with human intelligence only one moment on a continuum of sentience. Proliferating artificial hyperintelligences, cyborg hybrids, and domesticated robots promise uncanny new occupants for architecture, and the sociologist Anthony Elliott alerts us that these new friends will require “new models of identity and personhood, social relationships, family and friendship formation, gender and sexuality.”1 In future homes and cities, human relations with these intelligent and autonomous entities will demand a fresh sociology. Are these new interlocutors appliances? pets? animals? aliens? persons? Is architecture prepared for self-aware, self-caring, and self-owning robotic occupants?

The anthropocentric nature of architecture would seem sacrosanct and axiomatic. Yet since at least the industrial revolution, entire building typologies—factories, warehouses, airports—have been given over to the demands of machines, tailored to the peculiar needs of their technological occupants. What is new today is the ever-more pronounced volition, desires, judgement, and agency of the machines themselves, and their increasingly animal-like self-determination. Architecture that is now designed hermetically for and by humans may be punctured under the demands of our multiplying mechatronic co-habitants, exploding notions of households, cities, and who—or what—architecture is for.

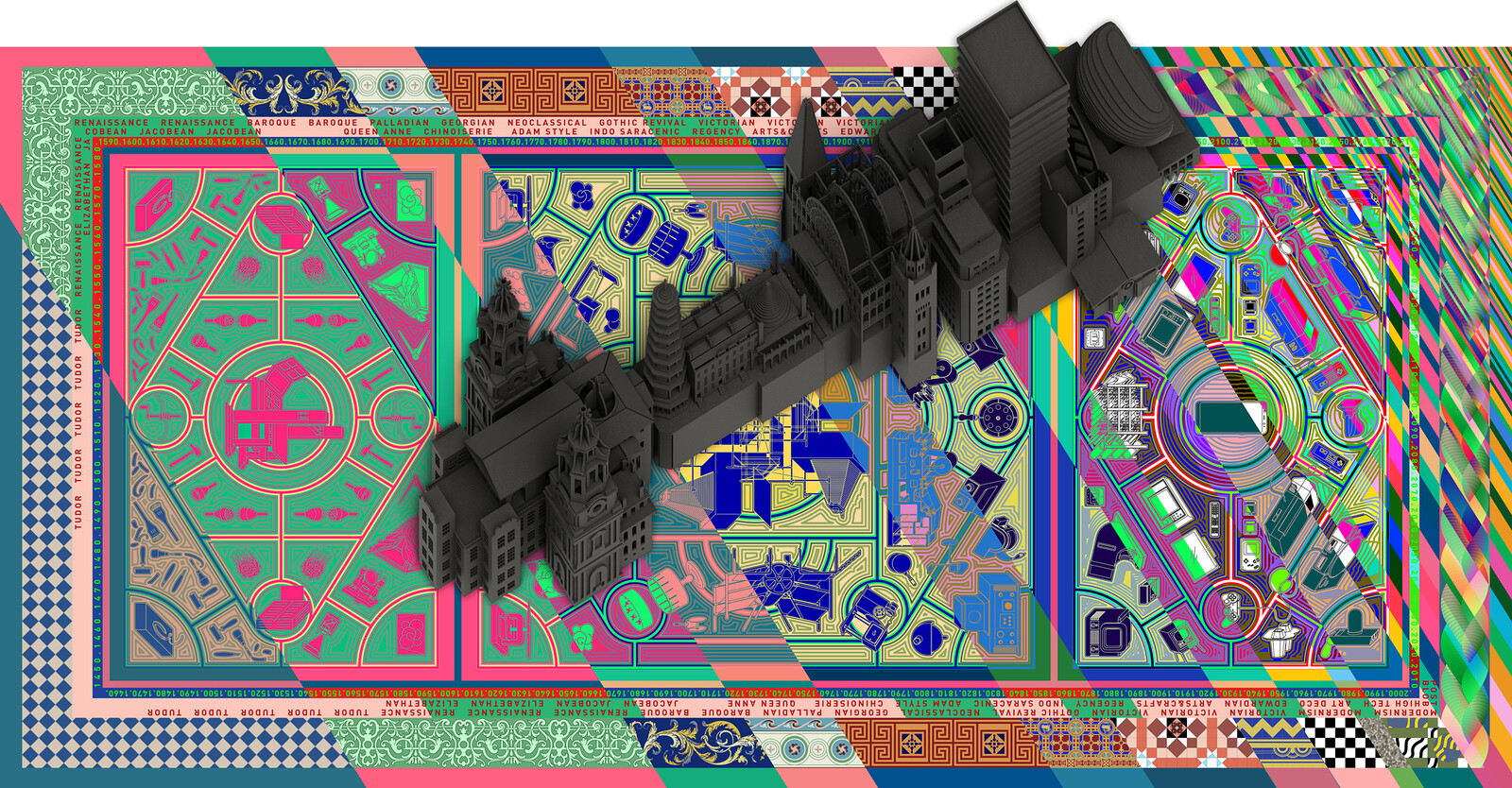

Animal-like manifestations of autonomous objects that might inhabit architecture. Certain Measures featuring Clement Valla, Home is Where the Droids Are (Projection), 2019.

Gardens and Jungles

Two countervailing archetypes wrestle in architectural fictions of artificial intelligence: the unitary hive super-consciousness on the one hand, and the society of individuated and autonomous intelligences on the other. These two myths—the cyber-brain and the cyber-zoo—have woven themselves into contested visions for architecture’s future.

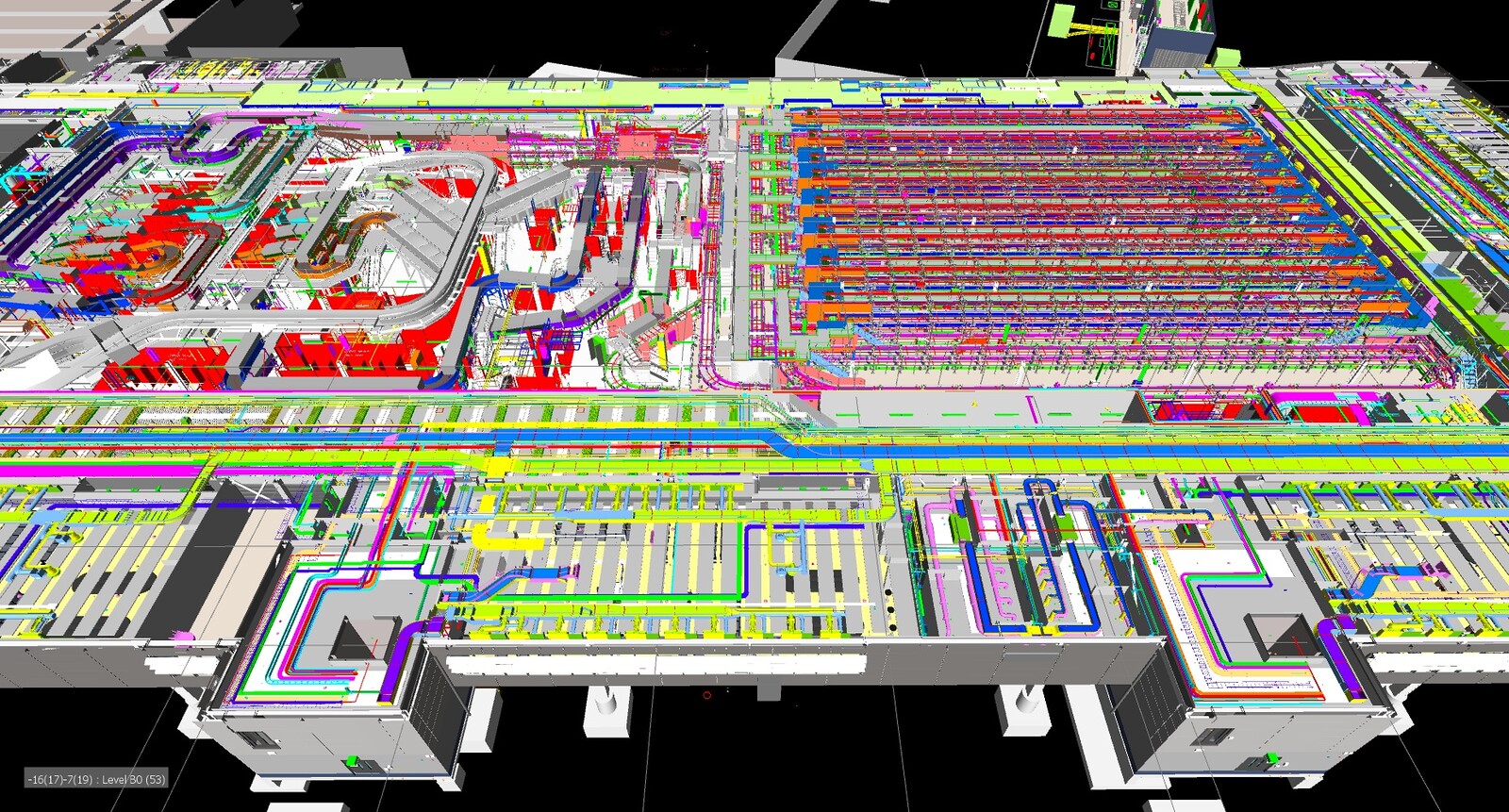

The cyber-brain, in natural reflection of anthropocentrism, is the perfect manager and paternalistic steward of civilizations and households. It is a governor of the macrocosm of the smart city or the microcosm of the smart home. The home and city are two sides of the same neural coin: the conduits, routers, broadcasting stations, relays, and other synapses of telecommunications infrastructure that now penetrate deep into the joints and sinews of artificially intelligent homes also innervate and infiltrate the city at large, binding the two in a common ecosystem. The home is an intimate node and interface in a larger dendritically connected system of services, technologies, and robots, part of the filigreed meshwork that sustains contemporary urban and global life.

“In large contemporary urban [systems],” Japanese architect Kenzo Tange proclaimed in 1972, “communication networks twist and intertwine into a complex which must be something like the nervous system of the brain… Large metropolitan areas or megalopolises in our day are becoming the brains for the body of modern society.”2 Architects like Tange have been thinking about artificial intelligence as an urban public utility for decades. This cyber-brain could be res publica, a collective computational utility and a communal basis for urban life and culture. This network would moderate aspects of the life of the city—from the synchronization of the myriad traffic systems to the regulation of an intricate artificial climate—all at a scale never before conceived. Tange hinted at a matryoshka doll of artificial intelligences nested from the global to the human scale that our reality seems to increasingly become. The citizens of Tange’s future—and our present—are not only humans in social relationships with each other but also with a panoply of electromechanical robots and furnishings at every scale. Governing them all is the ur-brain of the city, suspended in the matrix of a meta-autonomous nervous system that regulates this well-tempered new Eden.

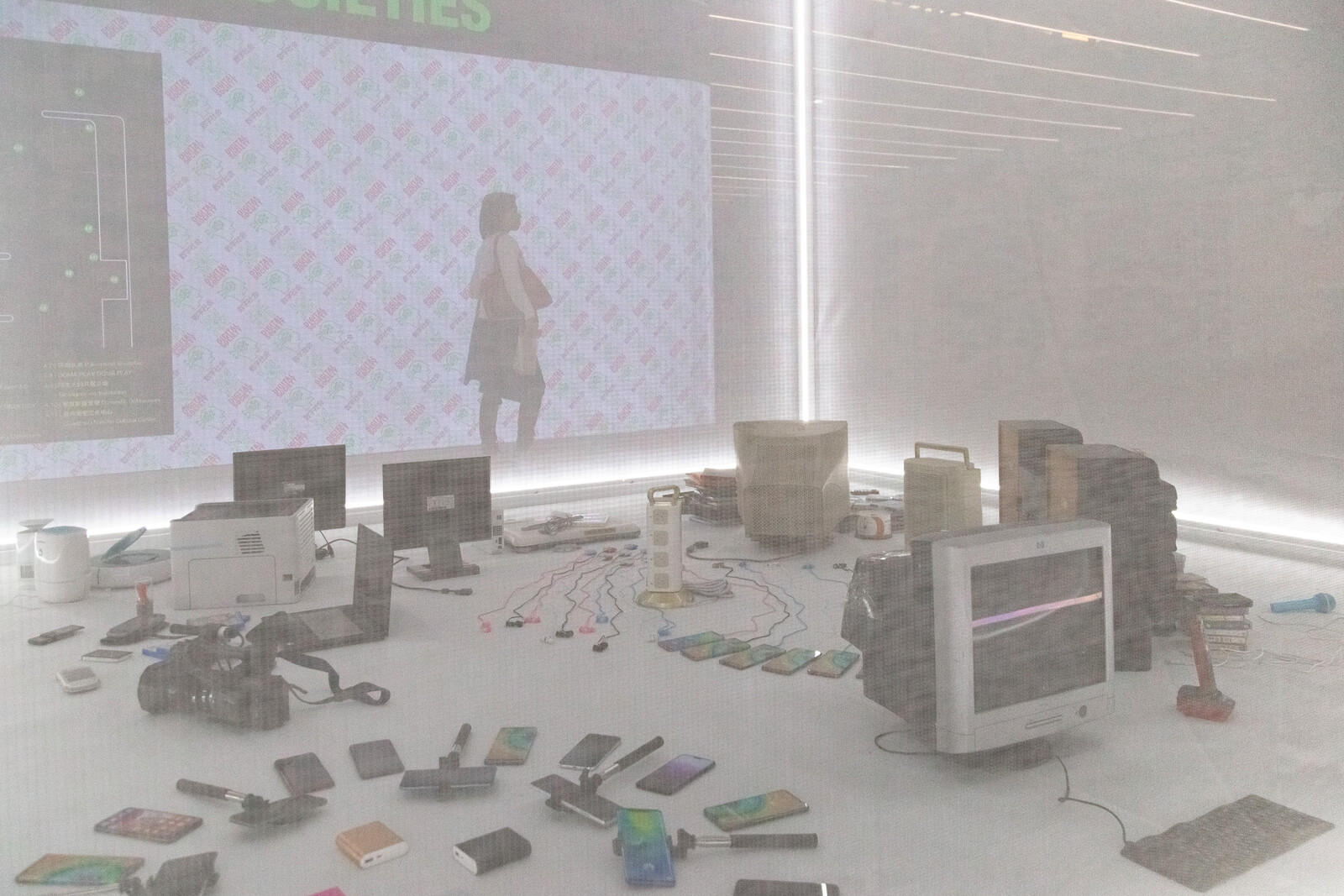

The vast pristine nervous system of the urban or planetary brain stands in contrast to the chaotic jungle of minor artificial intelligences of every description that act in their own interests and from their own quasi-passions. In the catalog for the 2020 Centre Pompidou show “Neurones,” Frédéric Migayrou notes that many early pioneers of artificial intelligence created a “cybernetic zoo” of “machines taking the form of varied animals: foxes, ladybugs, turtles… anticipating current neural applications, from connected systems to autonomous cars.”3 Like any other intelligence, the artificial kind is always embodied, poured into the electromechanical vessels that proliferate across the world. Artificial intelligence today expands urban and global cognitive infrastructure into a social galaxy that incorporates humanity alongside constellations of other intelligences. In this new chain of being, artifacts that were once unambiguously mechanical are on the verge not only of imitating the natural world but of promiscuously hybridizing with it. Cyborg plants and self-driving pets are just a few of the surreal new creatures we may soon share our lives with. This techno-biological entourage becomes a kind of new nature, cocooning us in a city/jungle of strange new delights and perils.

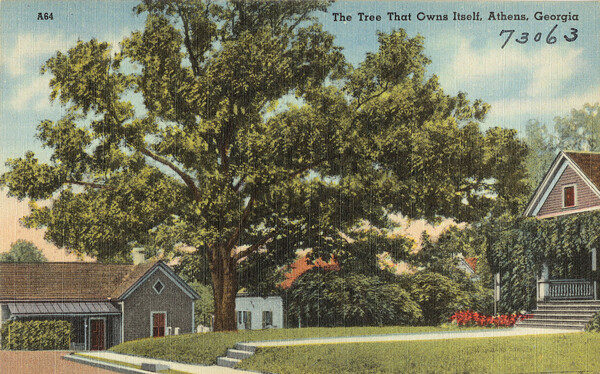

Postcard of the tree that owns itself in Athens, Georgia, ca. 1930s. Source: Boston Public Library/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons.

The odd consequences of our new companions extend to the legal and economic relationships between humans and non-human agents. In fact, artificial intelligences channel long and latent controversies of self-owning objects. The scholar of property Russell Belk has ventured that such entities may have agency in all respects, including “behaviorally, legally, and morally.”4 Consider the case of a tree in Athens, Georgia, USA that was allegedly deeded its autonomy by its loving owner around the 1820s. “W. H. Jackson, for and in consideration of the great affection which he bears said tree, and his great desire to see it protected has conveyed … unto the said oak tree entire possession of itself and of all land within eight feet of it on all sides.”5 More recently, thinkers like Mike Hearn have considered the legal and economic implications of self-owning cars,6 while economists like Geerat Vermeij have argued that economic logics extend to animal and non-human actors.7 The former animal trainer and current AI researcher Heather Roff puts it this way: “animals and animal training can teach us quite a lot about how we ought to think about, approach and interact with artificial intelligence, both now and in the future… It can also help us think about how best to teach these systems new skills and, perhaps most importantly, how we can properly conceive of their limitations, even as we celebrate AI’s new possibilities.”8

Pets as Technology, and Vice Versa

Though they are not machines in the ordinary sense, for millennia pets have occupied a gray zone between family members and technical devices. On the one hand, as historian Kathleen Walker-Meikle observed, they are “pampered and treated like members of the household,” adopted into intimate domestic arrangements.9 They have particular kinds of rights and agencies, and are often assumed to have a measure of consciousness. In defense of the animal mind, philosopher David Hume famously argued that “no truth appears to me more evident, than that beasts are endow’d with thought and reason as well as men.”10 Pets are well-recognized legal subjects to laws of divorce custody and even trust settlement.11 They have identifiable preferences, desires, and affections. Humans often feel a quasi-ethical responsibility to spatially accommodate them, and their occupancy in turn inflects the tone of space.

On the other hand, they fulfill pragmatic functions and act with delegated authority or apparent fidelity, from guarding homes and shepherding livestock to catching rodents and furnishing emotional support. They warn of danger, act out of loyalty, and even occasionally play the hero. We have welcomed them into the halo of the human family. Imagery sanctifies this entry into the familial pantheon. Literary theorist Ron Broglio has noted, for example, that as cattle was domesticated and corporeally reshaped, they also enjoyed their own peculiar mode of portraiture.12 (The ersatz cat portrait is a related contemporary instance of such practices). Yet even in portraiture, animals do not escape their technological roles: “While invoking the picturesque, the portraits almost always show the cattle in a typically un-picturesque pose, either the full flank of the right side or the left, at a right angle revealing its anatomical structure. The viewer can then observe the various cuts of meat, which remain the final purpose of breeding.”13

Pets—and animals generally—furnish a range of archetypes for how humans might encounter other species of quasi-technological intelligences. One need not espouse René Descartes’ dim view of animals as pseudo-mechanical automata to see a kinship between them and increasingly sophisticated robots. In her book Animal Alterity: Science Fiction and the Question of the Animal, Sherryl Vint calls for “potentially subversive and new ways of conceiving species interrelations.”14 Technology today is taking on the empathic qualities of the hyperintelligent pet, thoroughly domesticated to quotidian lives. The purring cat now frolics alongside whirring new kinds of robotic organisms. Like pets, these embodied intelligences are not precisely persons in an ethical and legal sense. For now, at least, like pets, the law classes them as property. But they are also quickly escaping the category of pure appliance to a life of leisure, espousing their own tastes, affinities, and hopes. They populate the domestic field on the ample and bourgeoning ontological spectrum between furniture and humanity.

Autonomy implicates mobility, and as previously fixed appliances sprout wings and wheels, furniture takes flight as a new wildlife. Homes no longer need to be bounded and static spaces or managed by benevolent house-brains but instead could be unbundled into autonomous technological services orbiting the occupant, each with their own agenda and social capital. These devices shuffle and inflect the human choreography of life in a swarm-like dance of autonomous machines.

What will become of our kitchens and living rooms as they themselves become jungles, dematerialized into the on-demand realm of domotic services? Virtually every action of our lives, even the most mundane or intimate, is being atomized into specific, discrete, purpose-built physical technologies or robots. Each device is intelligent and independent enough to obviate the need for a controlling major domo of the cyber-brain. Instead, a self-organizing entourage of drones, droids, robots, smart objects, and other digitally augmented devices may be orthogonally synchronized with the specific minute-by-minute actions of domestic life. With drone furniture, time and space are radically compressed and the house becomes a kind of vertiginous temporal transformer, teeming with new mechanical life.

If we relinquish the limiting inclination to humanize technology, we can embrace its animal instincts. We can trade the illusion of the garden for the exhilarating life of the jungle. The household expands to encompass a much richer range of members, species, and relations. This loose confederation of intelligent furniture-pets becomes a political construct as much as a spatial or technological one, a new domain of friendship and kinship. It is impossible to anticipate how architecture might respond to this new contingency of intelligent machines, whether to retrench in stolid firmitas or to dematerialize architecture itself into collectives of autonomous and self-organizing entities. But it is certain that both building and city will be subject to strange demands, opportunities, and entreaties from humanity’s disorienting new companions. Having tamed the domestic animal, we now encounter feral and unpredictable artificial intelligences. We cultivate together a jungle of technological delights, innocents in a state of neonature.

Anthony Elliott, The Culture of AI: Everyday Life and the Digital Revolution (London: Routledge, 2019).

Kenzo Tange, “Movement of ideas and information,” Ekistics 33,no. 197 (April 1972), 340.

Frederic Migayrou, “Cyber-Zoo,” in Neurones (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 93).

Russell Belk, “Consumers in an Age of Autonomous and Semi-Autonomous Machines,” in Contemporary Consumer Culture Theory, John F. Sherry and Eileen M Fischer, eds. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2017), 6.

Lucian Lamar Knight, A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians vol. 3. (Chicago: Lewis Publishing, 1917), 1446.

Russell Belk, “Consumers in an Age of Autonomous and Semi-Autonomous Machines,” in Contemporary Consumer Culture Theory, John F. Sherry and Eileen M Fischer, eds. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2017).

Geerat J. Vermeij, Nature: An Economic History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 39.

Heather Roff, “How Understanding Animals Can Help Us Make the Most of Artificial Intelligence,” The Conversation, ➝.

Kathleen Walker-Meikle, Medieval Pets (Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, 2012).

David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1888), 176.

Jeffrey N. Pennell, Alan Newman, Estate and Trust Planning (New York: American Bar Association, 2005), 243.

Ron Broglio, “The Romantic Cow: Animals as Technology,” The Wordsworth Circle 36, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 48.

Ibid., 49–50.

Sherryl Vint, Animal Alterity: Science Fiction and the Question of the Animal (Liverpool University Press, 2010), 21.

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).