It is timely to write a self-reflexive account of building the permanent architecture collection at M+, a museum for visual culture encompassing visual art, moving image, and design and architecture, just when the opening displays are being installed and when the city is once again at the precipice of historical change. This journey began in Hong Kong in 2013, while planning for the exhibition Building M+: The Museum and Architecture Collection, and continued on to Singapore, Taipei, Jakarta, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Colombo, Yogyakarta, and back again to Hong Kong in 2019. Throughout, I scoured through homes, offices, and storages for archives, drawings, models, and their stories. While just a slice of the curatorial team’s process and approach to collecting, the following moments represent how personal convictions in historicizing design have intertwined with an institutional remit of building a collection that is rooted in Asia with a global perspective.

I am a Mandarin-speaking Chinese Indonesian who grew up in Singapore, and a historian keen on reconstructing under-represented narratives of design and architecture across Asia. Within the curatorial team, I initiated research on and was responsible for proposing key works that can represent the momentous changes that took place in architectural production in Hong Kong, mainland China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia since the mid-twentieth century. Far from representing the entirety of my research and what I’ve acquired for the collection, these selected encounters highlight the specific nature and challenges of building a collection in a region where up until now, most museums have not deemed design and architecture worthy of research, conservation, and display—or if they do, their collections are largely built on nationalist agendas.

Each episode presented here prompted me to reconsider pre-existing assumptions and conventions relating to the criteria and conditions that define a work’s canonical value, museum-worthiness, authenticity, authorship, its material state, as well as larger questions of geographically-specific purposes of collection-building and exhibition-making. While some questions still linger, the past eight years have been an exercise of learning by doing. Despite some rejections and being occasionally perceived as part of a neo-colonial machine acquiring works of national significance across Asia, the team has trudged through with clarity on how and what we collect, the transnational connections we need to reveal in the stories we tell, and the value of expanding the canon beyond the widely-published references from Europe, America, and Japan that we often cite and praise. It has also been heartening to see our activities inspire similar initiatives among collecting institutions and historians in the region in documenting and stewarding architectural archives.

With the tumultuousness of today’s times, from the closing of borders to changing institutional priorities, such a gumptious curatorial methodology to collecting may be more challenging for the years to come. Nevertheless, the collection archives live on in M+’s Research Centre and as searchable bytes of formerly-unknown entities, and a sense gratitude remains for being part of its beginnings.

Painting of Exchange Square by Remo Riva of P&T Group, among maquettes of office towers Riva designed. Photo by Shirley Surya, Hong Kong SAR, China, June 2013.

Palmer and Turner

The first year of building the M+ architecture collection was akin to scavenging. We began with a search for projects that contributed to the most emblematic urban forms, typologies, and landmarks of Hong Kong since the 1950s. While there was documentation of certain practices and projects, few process materials were systematically kept or institutionally collected. This was the case even for one of Hong Kong’s oldest architectural practice P&T Group (formerly Palmer & Turner), whose archive was said to be lost. Encountering the bright visual palette of the axonometric painting of Exchange Square (1981–1985) was a welcome relief, particularly when two-dimensional archival materials are the main medium of architecture collections. Five years on, P&T found its physical archive intact, and it is now part of the collection of M+ and the University of Hong Kong.

Architects Team 3

Architects Team 3 (AT3) and its predecessor, Malayan Architects Co-partnership (MAC), were a major force in post-colonial architectural developments in Malaysia and Singapore from the 1960s to 1980s. Its legacy, however, was not kept by AT3’s third-generation directors. The “old stuff”—documenting formative days of the practice—were already half disposed upon my visit to their office. MAC and AT3, particularly under the leadership of Lim Chong Keat, designed key landmarks that reflected the city-state’s secular bid for modernity. While the firm is relatively unknown outside Singapore, their addition to the collection highlighted the relevance of acquiring works that represent architectural production in post-independence South and Southeast Asia. As the first archive of a practice outside greater China to enter the M+ Collections, AT3’s fragmented archive reinforced the museum’s regional focus and transnational interests.

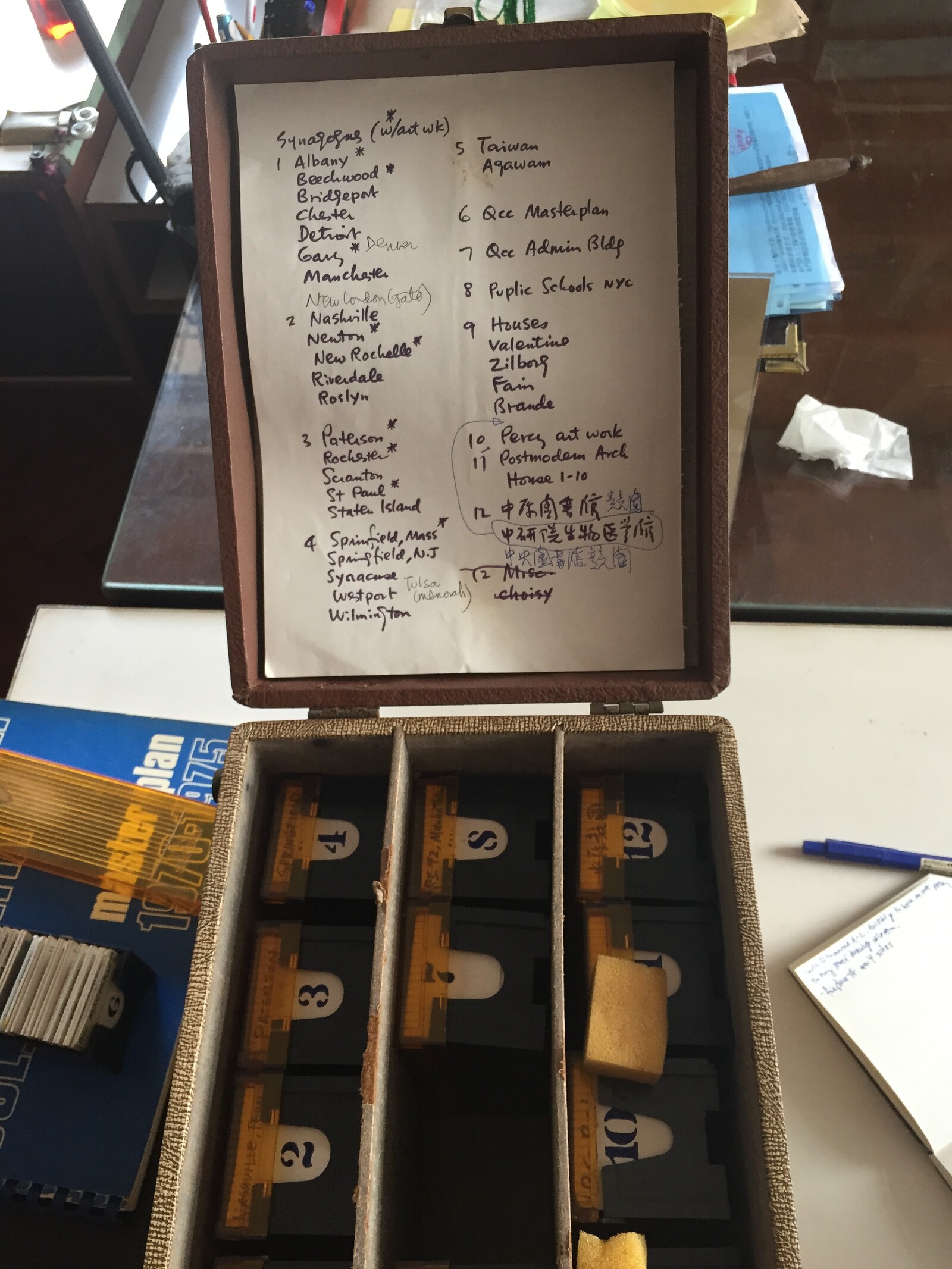

A box of slides documenting Wang Chiu-hwa’s projects in New York under Percival Goodman. Photo by Shirley Surya, Taipei, Taiwan, March 2015.

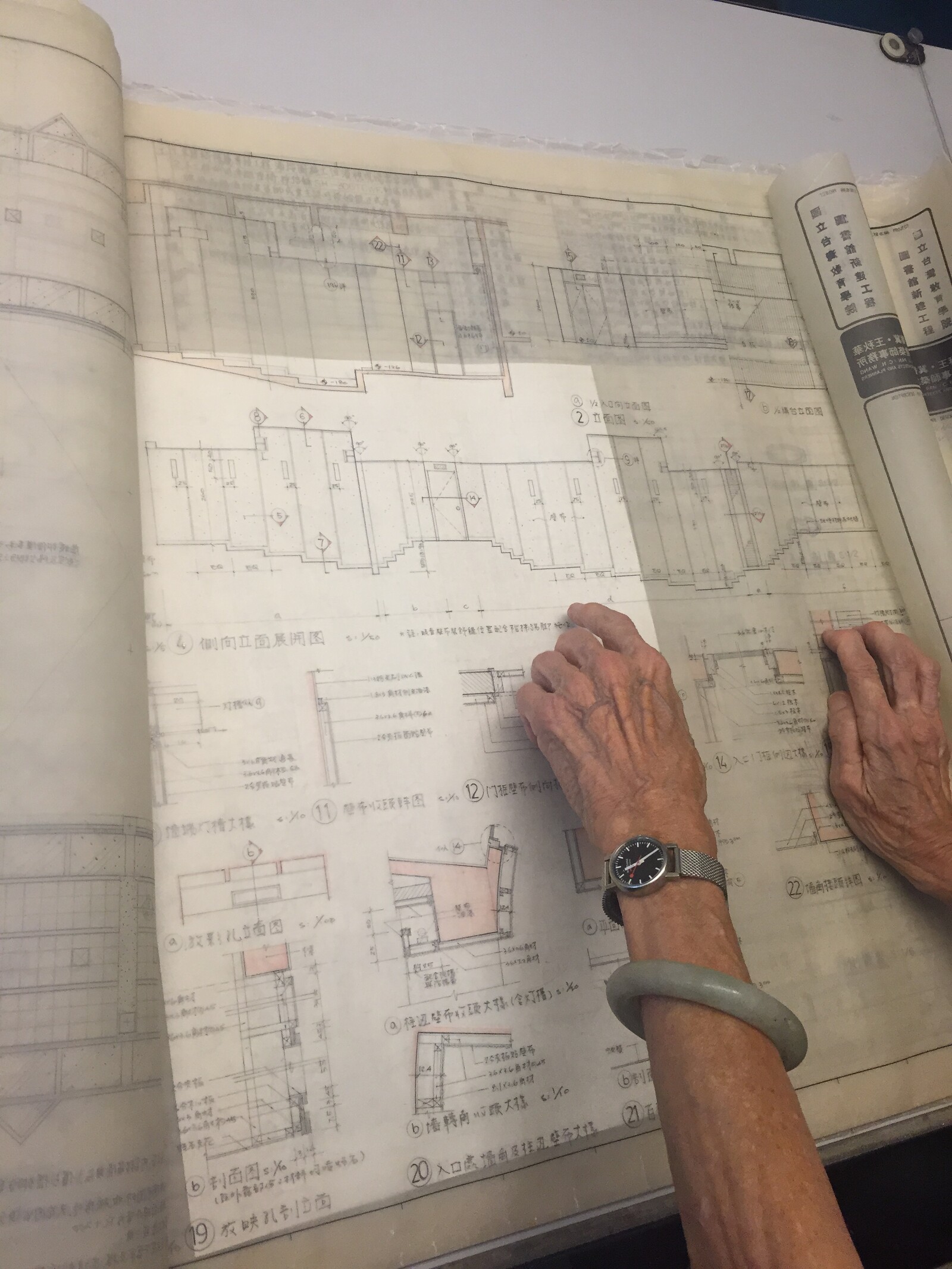

Furniture detail drawings for one of Wang Chiu-hwa’s first library projects in Taiwan. Photo by Shirley Surya, Taipei, Taiwan, March 2015.

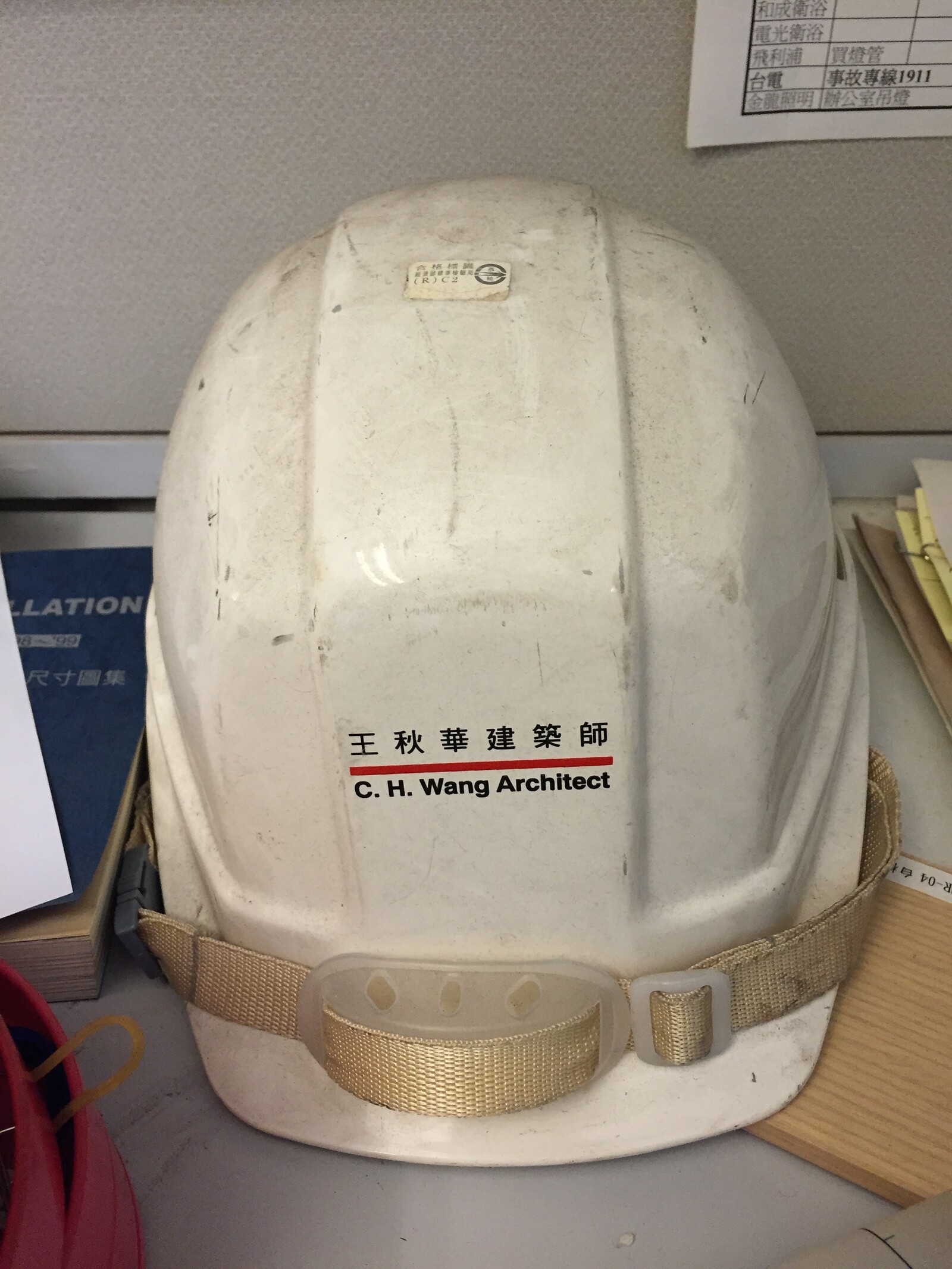

Wang Chiu-hwa’s hard hat, inscribed with her name, even as she practised under the firm J. J. Pan & Partners. Photo by Shirley Surya, Taipei, Taiwan, March 2015.

A box of slides documenting Wang Chiu-hwa’s projects in New York under Percival Goodman. Photo by Shirley Surya, Taipei, Taiwan, March 2015.

Wang Chiu-hwa

Wang Chiu-hwa practiced in New York for thirty years before returning to Taiwan in 1979. She was called “mother of libraries” for designing Taiwan’s first modern university libraries. While we considered collecting her archive a priority, her work lacks the usual canonical traits: they were not internationally published; the synagogues, schools, and industrial facilities she designed had no dramatic “auteur” qualities; and her authorship was often shared by the larger practice she was part of (the office of Percival Goodman in New York and Joshua Pan in Taipei). Yet, the necessity of making underrepresented women architects visible led me to reflect on and recalibrate the criteria for assessing value in architectural practice and discourse, and the museum’s role in shaping those values. Authorship needs to be attributed women architects working alongside prominent male architects, and to take into account “architecture for the little people,” which is quotidian yet rigorous and human-centred. Wang’s name did not appear on some of the blueprints, but we could recognize and acknowledged her authorship through her keen and in-depth explanation of each project she designed, including the steepness of steps to ease uphill access at Queensborough Community College and carpentry details of furniture for Chungyuan Christian University Library.

The unattainable model of Wisma Dharmala Sakti (now Intiland Tower) (1983-1985)—a fixture at the building’s Facilities Management Office. Photo by Shirley Surya, Jakarta, Indonesia, March 2017.

Wisma Dharmala Sakti, Jakarta, Indonesia

Unlike collecting art, collecting architecture is more often done without a mediator such as a gallerist or dealer. In sourcing an architectural artifact, one often has to go beyond the architects themselves and speak directly with the clients, especially when a practice has discontinued or when original models were thrown away due to storage limits. The model of Wisma Dharmala Sakti (now Intiland Tower), which was designed by Paul Rudolph and was an influential precursor to today’s “tropical high-rise”—was one example of such an arduous search, and with little promise of an outcome. In spite of efforts to convince the developer, it was impossible to acquire the model. I only had the privilege to see it. In the 1980s, the developer was bold to commission Rudolph to exercise his long-held concepts of the megastructure for an urban environment in Southeast Asia. Now, it is more important for the model to be a tangible reference for carrying out maintenance work than having it conserved or displayed for posterity.

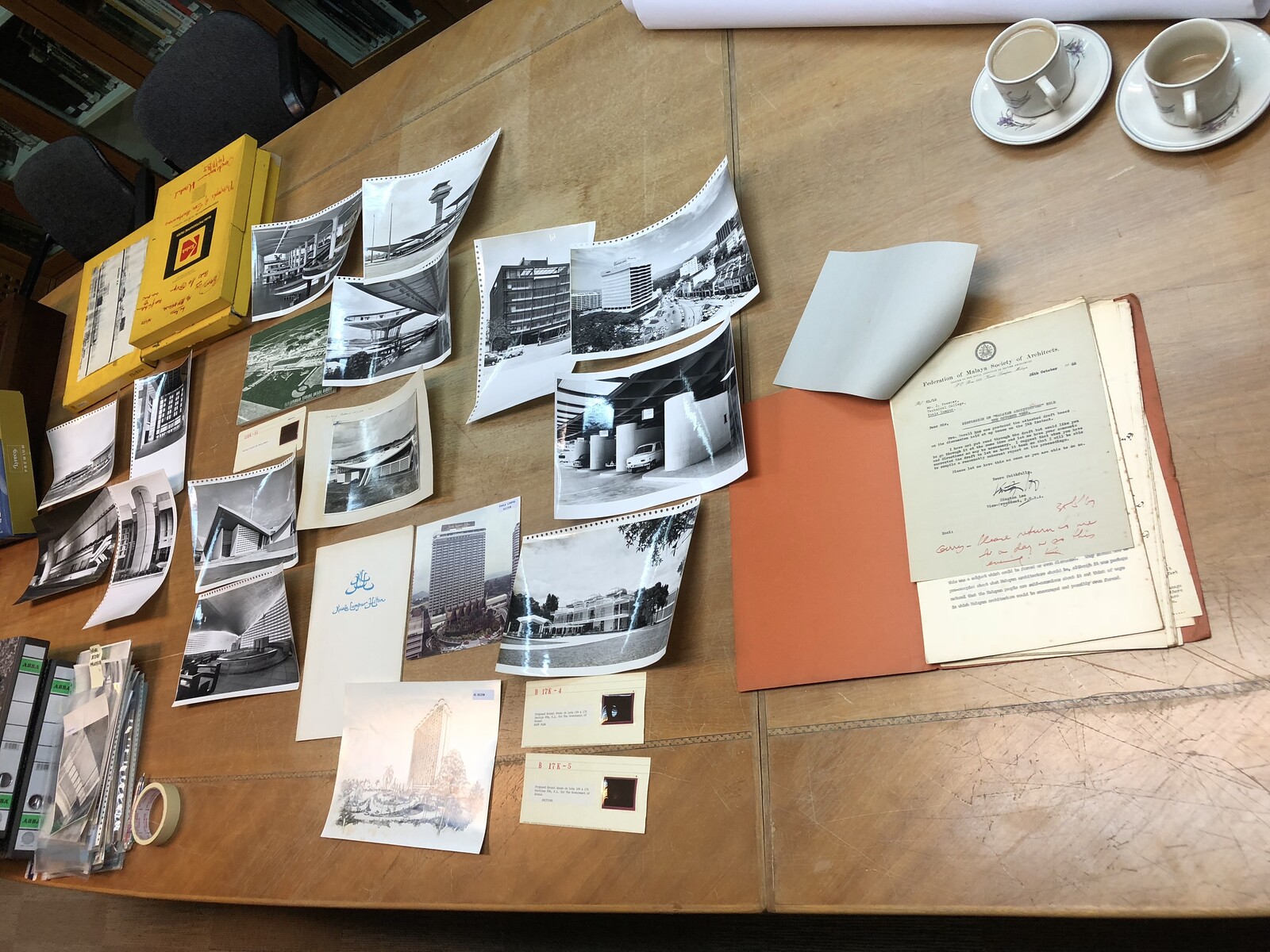

Booty Edwards & Partners

Acquiring the project archives of BEP Akitek (formerly Booty Edwards & Partners) was an exercise in clarifying the relevance of architectural archives from Malaysia to the museum’s research interests. It was also a result of serendipity and mutual affinity with the firm, who believed in our regional focus within a transnational framework. My inquiry—based on the scant literature on BEP Akitek—coincided with an exhibition Manifest: Modernism of Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur, which presented documentation of the firm’s contribution to architectural production in post-independence British Malaya. These included Malaysia’s first international airport, university campus, and international hotel, as well as Brunei’s mosques and government offices that were designed with shell-roof systems, exposed concrete, and anodized aluminum peaked roofs inspired by indigenous tradition. These projects reflected decades of the firm’s openness to multiple perspectives on how architecture related to identity, as well as an experimental approach to form, materials, and construction technology before the formal politicization of the “Malayan” style. Their archive also documented the roles of colonial architects, which some historians downplayed in favor of a nationalistic narrative. The archive of BEP Akitek shows how both foreign and Malaysia-born architects contributed to raising the standards of architectural production and imagination in Malaysia.

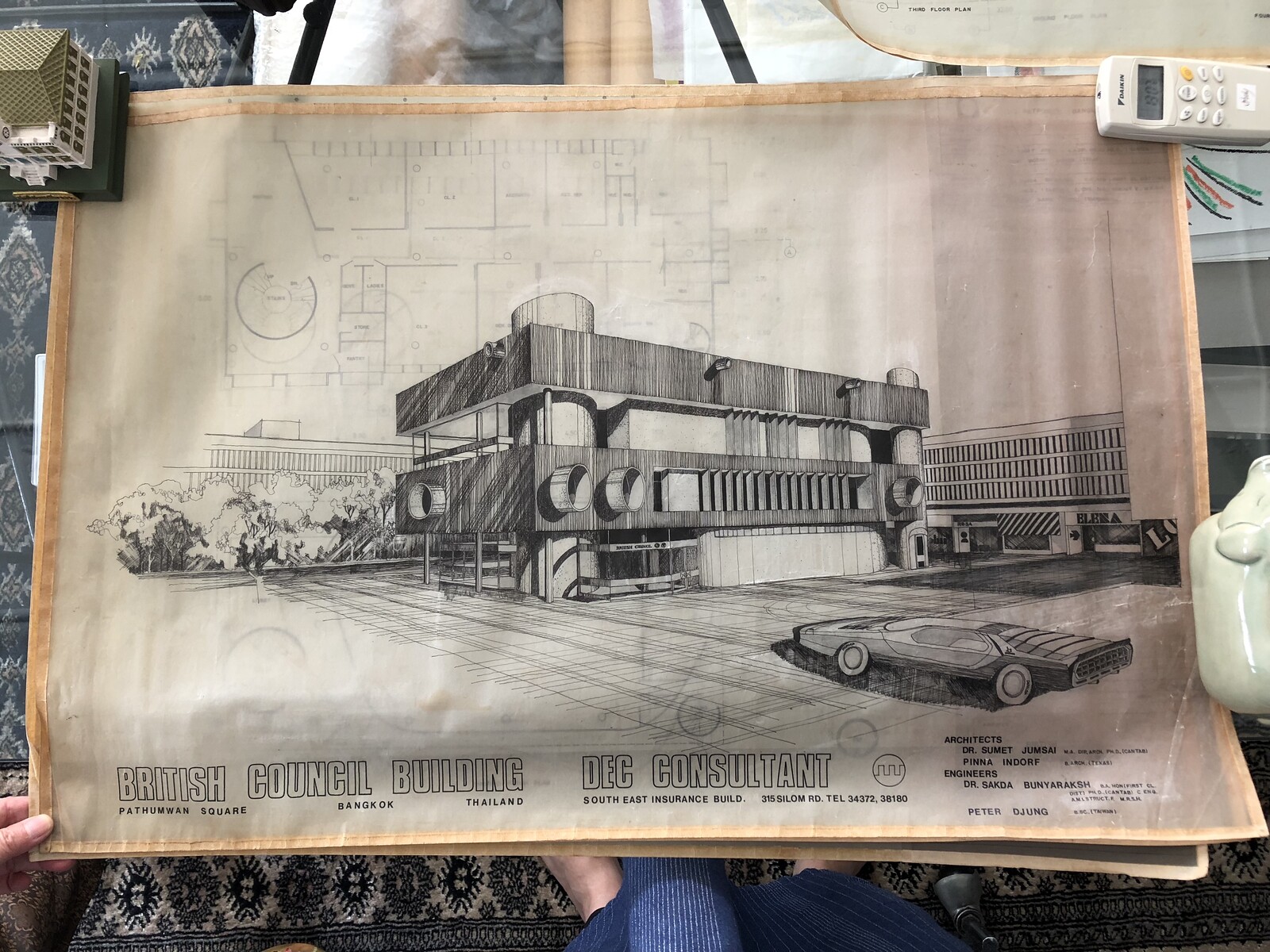

Drawing of Thailand’s first British Council, designed by Sumet Jumsai. Photo by Shirley Surya, Bangkok, Thailand, November 2017.

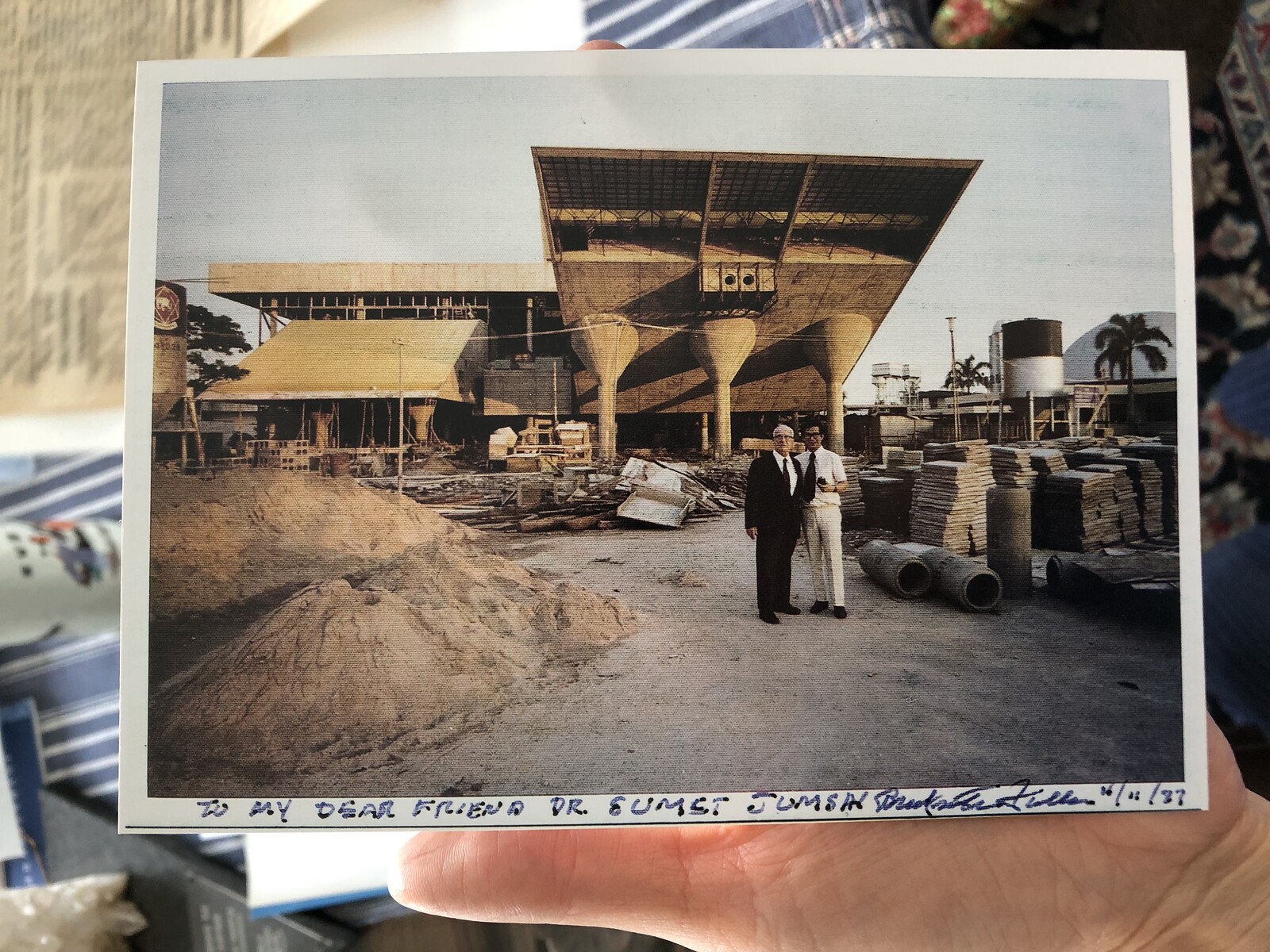

Photograph of Sumet Jumsai and R. Buckminster Fuller in front of the Bangkok Science Museum in 1977. Photo by Shirley Surya, Bangkok, Thailand, November 2017.

Drawing of Thailand’s first British Council, designed by Sumet Jumsai. Photo by Shirley Surya, Bangkok, Thailand, November 2017.

Sumet Jumsai

I’ve been questioned about acquiring the archive of Sumet Jumsai over other architects in Thailand. Jumsai’s work reinforces the rationale for collecting works that could, firstly, be in dialogue with local-regional-global phenomena, and secondly, have transnational affinities with a specific network of architects that are already in the M+ Collections. Jumsai’s projects—particularly the British Council Building (1969–1970), the iconic “Robot Building” (1983–1986), and Thammasat University Rangsit Campus (1984–1986)—reflect his critical engagement with the concepts of place and plurality within the rubric of architectural modernism, postmodernism, and regionalism. Jumsai participated in the Campuan thought-exchange platform organized by Malaysian architect Lim Chong Keat and R. Buckminster Fuller in Bali and Penang. He was also associated with the Asian Planning and Architectural Consultants, a regional network of architects that included Tokyo-based Fumihiko Maki, Singapore-based William S. W. Lim, and Hong Kong-based Tao Ho.

Comparative study of original design drawings, archival shots and on-site photographs of Negeri Sembilan State Mosque (1965–1967) to inform the reproduction of its model—the making of a capsule of collapsed times supervised by Lim Chong Keat, one of the co-founders of Malayan Architects Co-partnership. Photo by Shirley Surya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, January 2018.

Negeri Sembilan State Mosque, Seremban, Malaysia

Most museums look down upon having reproductions of models in their permanent collection. But the absence of original models is inevitable, especially those of architects who are no longer active, or who don’t have the luxury of space to store old models. At M+, we do not want to privilege the historicity of museum collections at the expense of the public’s understanding of architecture, and the physical representation of a design as opportunities for critical reflections. We have therefore agreed to acquire reconstructed models based on a set criteria: there had to be evidence of a model in the past; models had to be reproduced according to archival drawings of the original design or documentation of the built structure; and the model-making process has to be supervised or endorsed by the original architects. As the last mosque commissioned to non-Muslim architects before the onset of conservative Islamic nationalism in Malaysia and characterized by the sculptural malleability of reinforced concrete that made up its umbrella-shaped concave roofs, we felt the Negeri Sembilan State Mosque was significant enough to be reproduced in 2018 under the supervision of its lead architect, Lim Chong Keat, for the M+ Collections.

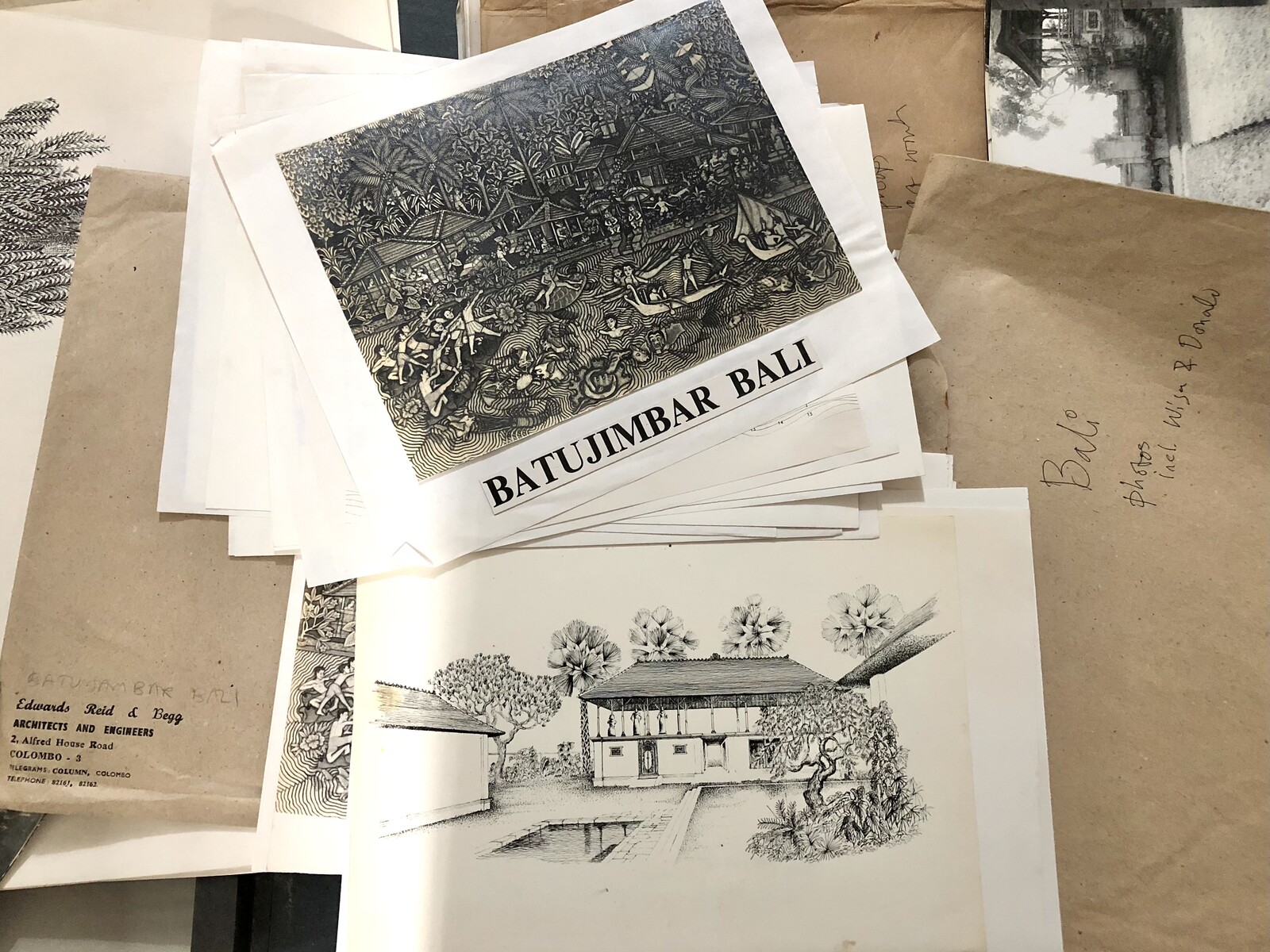

Photographs of key architectural sites in Bali taken circa 1973 by Geoffrey Bawa when he started designing the Batujimbar Estate. Photo by Shirley Surya, Colombo, Sri Lanka, January 2018.

Loose layout sheets of the Batujimbar Estate’s sales catalogue. Photo by Shirley Surya, Colombo, Sri Lanka, January 2018.

Photographs of key architectural sites in Bali taken circa 1973 by Geoffrey Bawa when he started designing the Batujimbar Estate. Photo by Shirley Surya, Colombo, Sri Lanka, January 2018.

Batujimbar Estate, Bali, Indonesia

Geoffrey Bawa’s fame is largely built on his canonical projects in Sri Lanka. However, the Batujimbar Estate in Sanur, Bali—Bawa’s second built project outside Sri Lanka—was an entry point to deepening my understanding of his practice. Batujimbar Estate is a project often cited by Singapore-based architects as a source of influence in the rendering of the tropical landscape and in the design of the “tropical resort” typology. It is a compelling example of a design dialogue between South and Southeast Asia. Bawa’s photographs and detail drawings of Bali’s built environment in the sales catalogue demystifies Bawa’s oft-presumed intuition. Instead, they reveal his studied approach in the simultaneous veneration and transformation of the Balinese bale (pavilion), which distinguishes the project’s design from those in Sri Lanka and India.

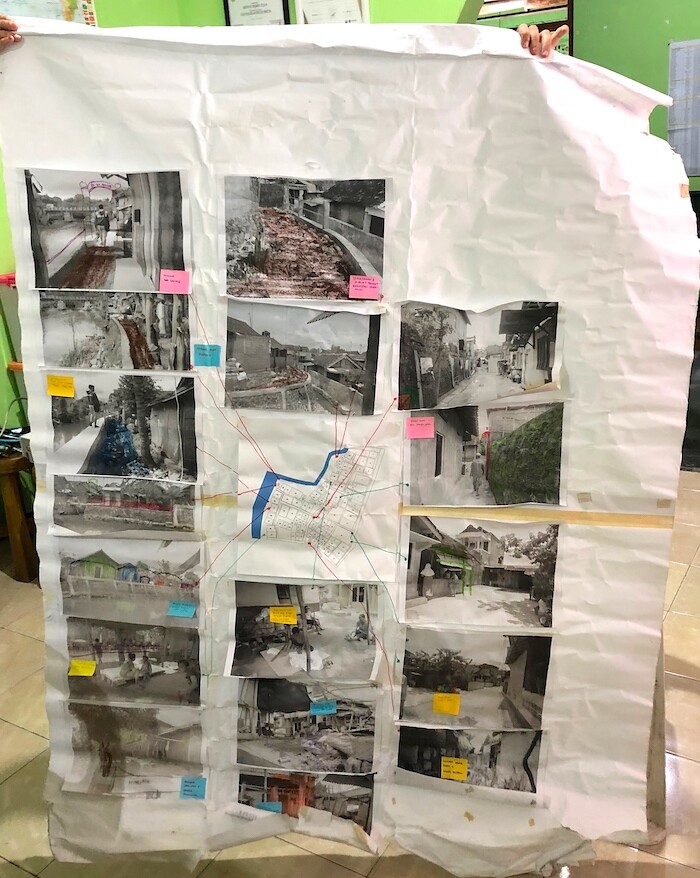

A 2-meter-long sheet of paper once used for discussion between ARKOMJOGJA and community members on the various micro-interventions to improve the conditions of an urban village in Yogyakarta instead of complete redevelopment and relocation. Photo by Shirley Surya, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, December 2018.

ARKOMJOGJA (ARSITEK KOMUNITAS JOGJA)

When I chose to approach Yuli Kusworo, co-founder of ARKOMJOGJA (Community Architects Yogyakarta), about collecting his archive, he was skeptical why a museum designed by Swiss architects would be interested in acquiring documentation of participatory design processes for urban village rehabilitations and post-disaster reconstruction projects which—if they still exist—are in very poor condition. There are many internationally renowned architects from Indonesia, as well as architects who were involved with the country’s nation-building project. But sharing with him how I’ve been tracing the lineage of design as a social practice in Yogyakarta—which he was an integral part of—convinced Kusworo to dig up materials from previous projects. This lineage began with the Aga Khan Award-winning Kali Code slum rehabilitation project by architect-priest Y. B. Mangunwijaya, who was a mentor to architect Eko Prawoto. Prawoto, who was known for his initiatives in designing for the urban poor and post-earthquake reconstructions, motivated Kusworo to establish ARKOMJOGJA as a relevant and much-needed alternative model to practicing architecture that responds to Indonesia’s specific socio-economic and environmental conditions.

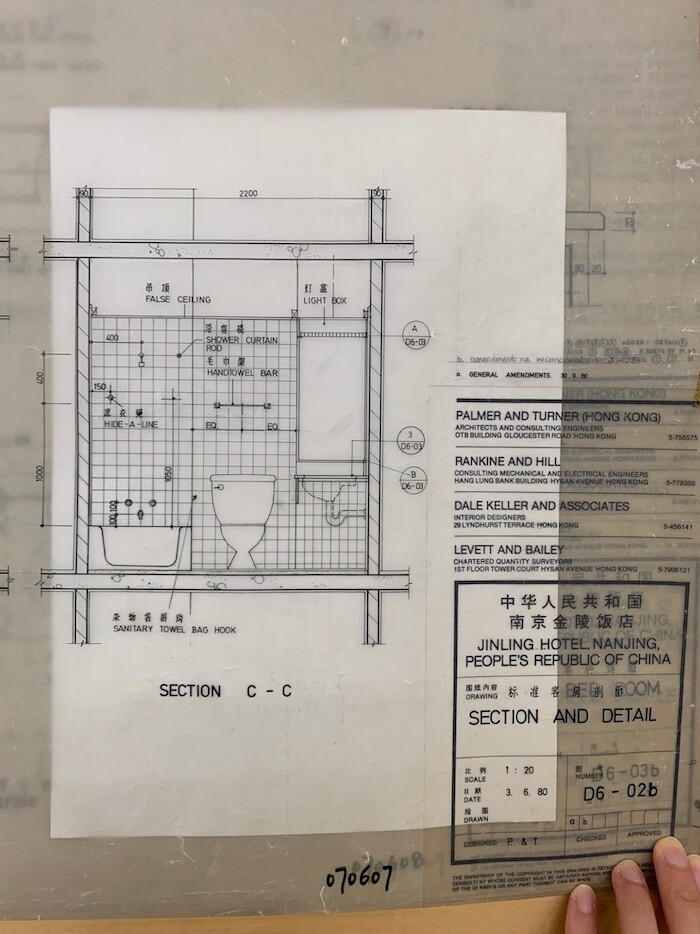

Placing a paper behind a blueprint for a clearer view of bathroom design of Jinling Hotel in Nanjing designed by Palmer and Turner, while reviewing the firm’s archive, miraculously found after 5 years of assumed disappearance. Photo by Shirley Surya, Hong Kong SAR, China, April 2019.

Jinling Hotel, Nanjing, China

A bathroom design of Jinling Hotel (1978–1982) appropriately reveals some distinct priorities we assume in building the architecture collection at M+. Firstly, hotel design—as a highly commercial endeavor—is rarely a glorified typology in architectural discourse or a museum’s collection. Yet, in early reform China, state-sponsored hotels were a powerful spatial and operational means to convey a visible sense of progress and opening up, without lessening the Chinese Communist Party’s overall position of power. Secondly, as one of China’s earliest high-rise hotels, the conception and execution of Jinling Hotel set the standard in the design and development of hotels and high-rise structures across China. The collaboration and knowledge transfer between China’s local design institutes and Hong Kong-based architects and American interior designer (who had designed the Hyatts and Hiltons across Asia) set the precedent for international, and later independent architectural developments in China. It was also an example of the much-forgotten contributions Hong Kong architects made to China in the early 1980s. As a project initiated by Singapore-based Nanjing-born entrepreneur S. P. Tao, Jinling Hotel was designed by Hong Kong-based Canadian-born Japanese James H. Kinoshita of Palmer and Turner, together with American interior designer Dale Keller. The project is entangled in a transnational capital flow and diasporic Chinese allegiance—historic signifiers that are just as important as the design of the hotel’s edifice.

Solicited: Proposals is a project initiated by ArkDes and e-flux Architecture.