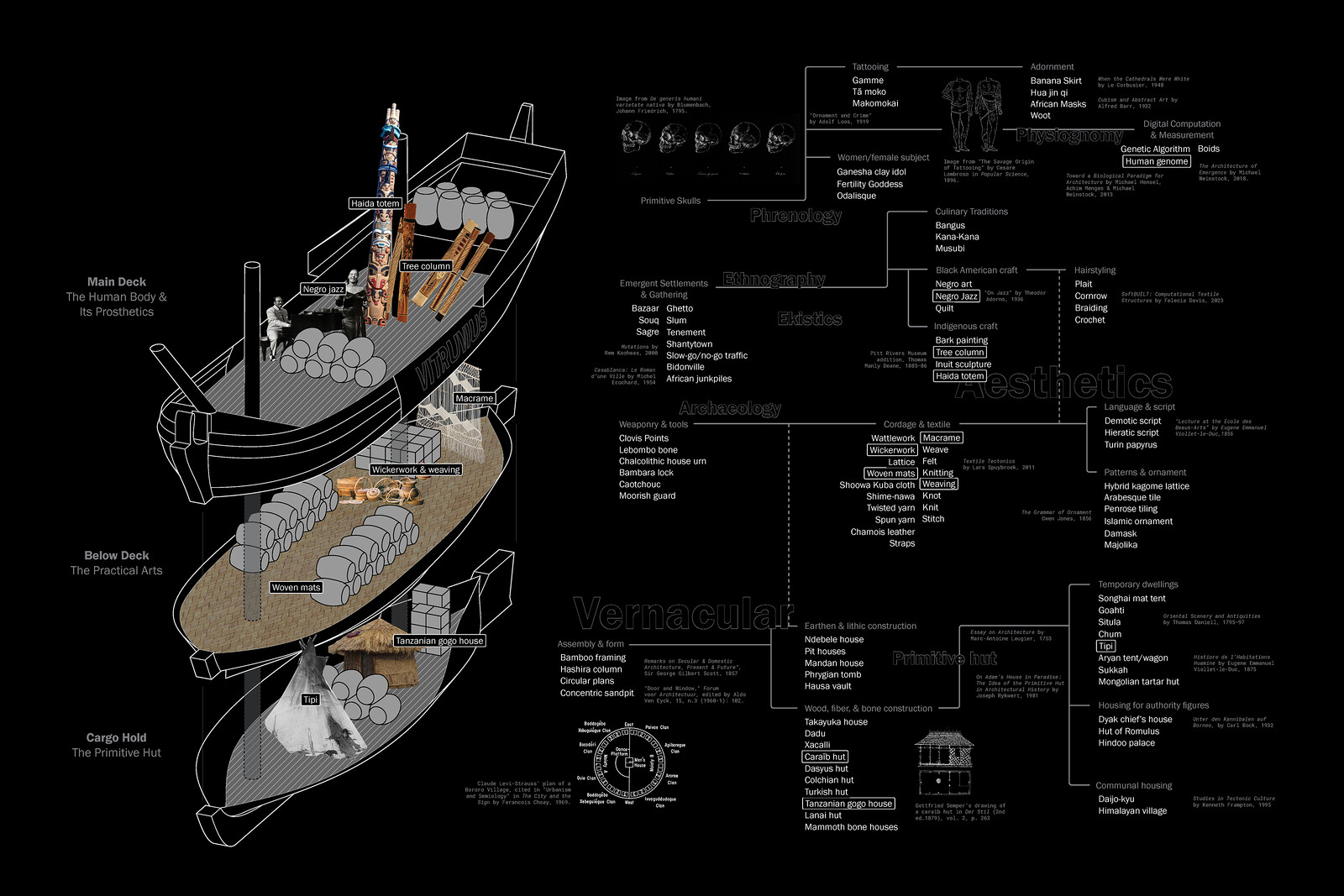

Architecture is—acid mine drainage, acrylic, air pollution, aluminum, arsenic trioxide dust, basalt, bauxite, Bayer process, biodiversity loss, black sand mining, blasting, bond-aid for plastering, butadiene, calcite, calcium oxide, capital, carbon, caustic soda, cedar wood, chromium, clay, clearances, coal, coastal, cobalt, concrete floor hardeners, copper, copper concentrates, cryolite, deforestation, depletion, desertification, dolomite, emulsion polymers, extraction, firwood, floods, fluorides, fly ash, foamed plastic, food insecurity, granite, gravel water, groundwater pollution or depletion, halogenated flame retardants, hauling, hemlock wood, hydraulic excavation, land grab, large-scale disturbance of hydro and geological systems, lead, limestone, lithium, loss of landscape, loss of vegetation cover, malachite, manganese, marble, mercury, methane, mine tailing spills, mining of silica sands, monopoly, mold releasing agents, mud disposal areas, mudflow, nepheline, nickel, noise pollution, oakwood, oil, oil shale, oil spills, open pit mines, ore, peat, pebbles, phenol-formaldehyde resins, pine wood, platinum, polyethylene, polymer bonding agents, polypropylene , polystyrene, porous volcanic tuff, quartzite, reduced ecological and hydrological connectivity, ripping, roasting processes, rock flours of volcanic origin, rosewood, sand, sand sediments, sand stone, saw dust, sealants, silica dust, slate, soda ash, soil contamination, soil erosion, spruce wood, styrene, surface retarders, surface water pollution, tar sands, teakwood, thermal cracking, timber, tin, titanium, toxic waste dumping, trass, uranium, vanadium, waste overflow, zinc—climate.

Architecture is climate.

Architecture is Climate entangles architecture with the conditions of climate breakdown. For too long architecture has stood outside climate, seeing it as a problem to be fixed through technocratic intervention. Architecture as part of the modern constitution carries a dualistic view of the world: humans and non-humans, nature and technology, culture and science. Our lives and societies are structured around this attitude. But what if, as Bruno Latour argues, we have been completely wrong?1 What if this polarity has never existed?

Architectures and climates are not separate entities brought together in orchestrated moments. Instead, they are conditions that are produced through one another. Without the pretence of a stable discipline producing fixed objects, architecture becomes part of a febrile and disrupted world, vulnerable to its contingencies. No longer standing outside and applying superficial patches to the wounds of climate, architecture is climate binds the discipline and its humans to the scars, violence, and emotions of climate breakdown.

We cannot continue to ask the normative question: “What can architecture do for climate breakdown?” Instead, we must ask: “What does climate breakdown do to architecture?” The architecture of the modern project has relied on extractive and combustive processes to such an extent that fuel has come to dictate form. Architecture has concretized our perilous energy dependency.2 Exposing these dependencies and reckoning with their causality of climate breakdown is the first step towards deconstructing and reforming the discipline of architecture. But rather than face this state of addiction and tackle the causes of climate breakdown, architects tend to tackle the symptoms.3 Akin to sticking a band-aid over a wound, practicing architecture as technocratic fix only perpetuates historical privileges and oppressions. Architects often want to lead the world on a path of progress that learns selectively from history (aesthetic canons, individual heroes, technical breakthroughs). Practiced in this amnesiac manner, architecture ends up repeating its hubris, its mistakes, its isolation, as if the master’s tools can both dismantle and rebuild the master’s house.4

Both material and social-cultural, both product and agent, architecture and climate therefore also have an opportunity to create alternative material and social-cultural configurations that nurture a different set of forces and functions. If architecture is climate, then climate breakdown is inherently accompanied by an architecture breakdown as well. Responding to the urgent need for reinvention in the way we understand, practice, and teach architecture demands an engagement with activism, politics, and education. Architecture must become relational, subjective, and interconnected; both planetarily bound and supported; inclusive beyond the human; caring, curious, and brave.

Architects can become part of the systemic change that climate breakdown calls for, reshaping social relations through alternative spatial formations and practices. Neither fixed nor rigid, other possible architectures are also other possible climates. Together, both might change and be changed.

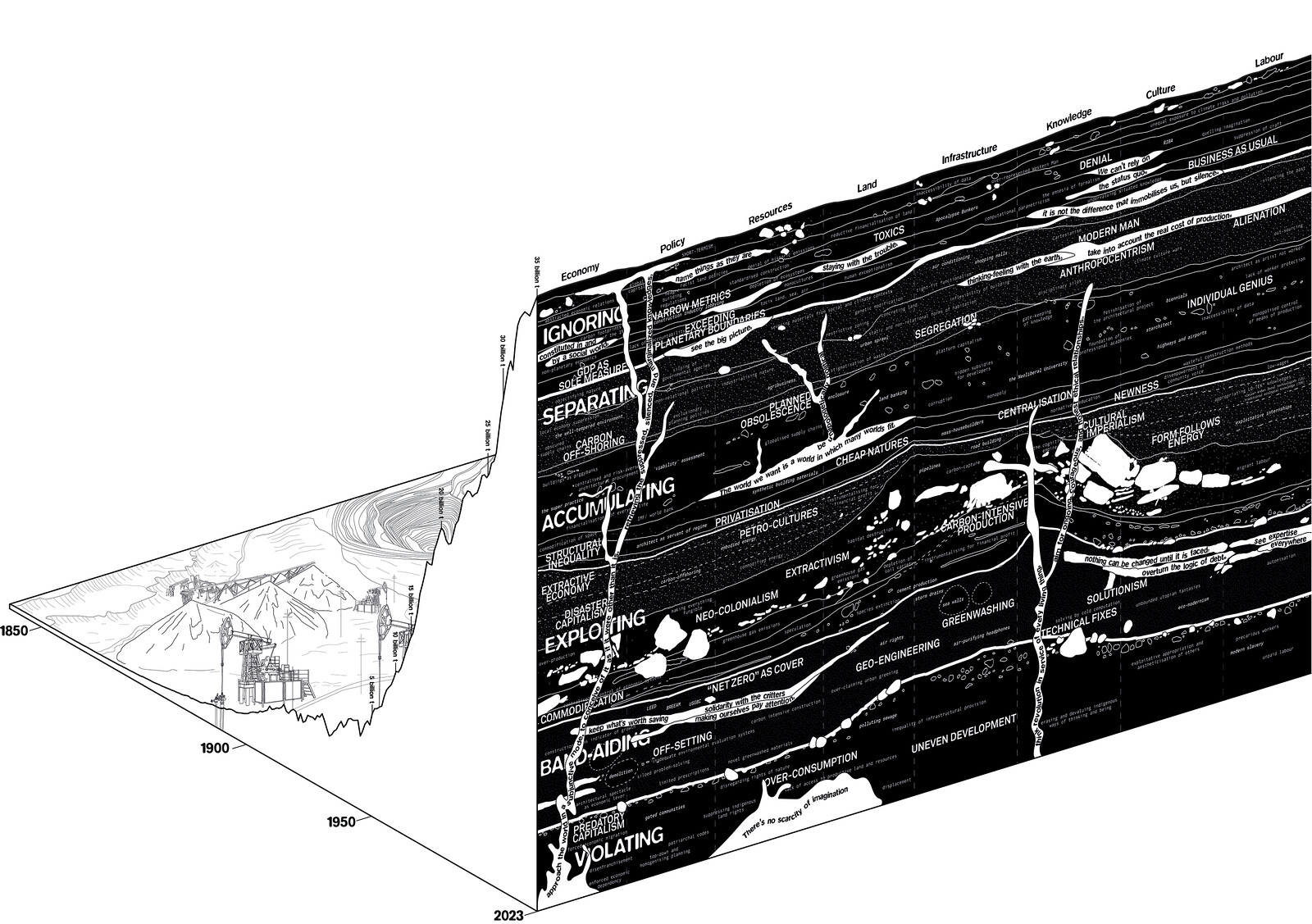

The Mountain

The diagram is inspired by the nineteenth-century German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and his scientific illustrations of the natural world, in particular the famous mountain “maps”. These show the way that climate, geography, nature, and humans are interconnected. “Everything,” Humboldt said, “is interaction and reciprocal.”5 Humboldt systematically documented and understood the impact of human action on natural world, highlighting the way that colonialist interventions upset ecological balances.6

Our mountain is one of global heating, tracing the rise of atmospheric CO2 emissions against a linear time scale. The ubiquitous rising line of greenhouse gas emissions is not an empty abstraction, but is built on extractive practices. It is also a line that needs to come down.

The Sediments: Ignoring, Separating, Accumulating, Exploiting, Band-aiding, Violating

The mountain is cut along the axis of the present to reveal various layers, the sediments that have collectively produced the inexorable steepening of the mountain. Each of the six sedimentary layers is identified by a verb describing the forces that have accelerated the production of CO2 in relation to the production of the built environment.

Humboldt talked of man’s “lethal mixture of vice, arrogance and ignorance” in relation to the natural world. Tragically, these malign traits have been reinforced and extended in contemporary conditions. Our verbs describe the violence of capitalism’s imperative of endless growth, and the modes of thought that appropriate nature and labor in an exploitative manner. They indicate the causes rather than the symptoms of climate breakdown, and so in turn describe the conditions from which modern architecture has arisen, and by implication, the forces that future architectures must face and resist.

The Sites: Economy, Policy, Resources, Land, Infrastructure, Knowledge, Culture, Labor

Within the sedimentary layers are more particular conditions arranged on a vertical matrix that identify the contexts in which climate and architecture are entangled. Rather than describe these sites in geographical or topographical terms, they are understood thematically as sites where climate/architecture are produced, and thus are sites of potential intervention.

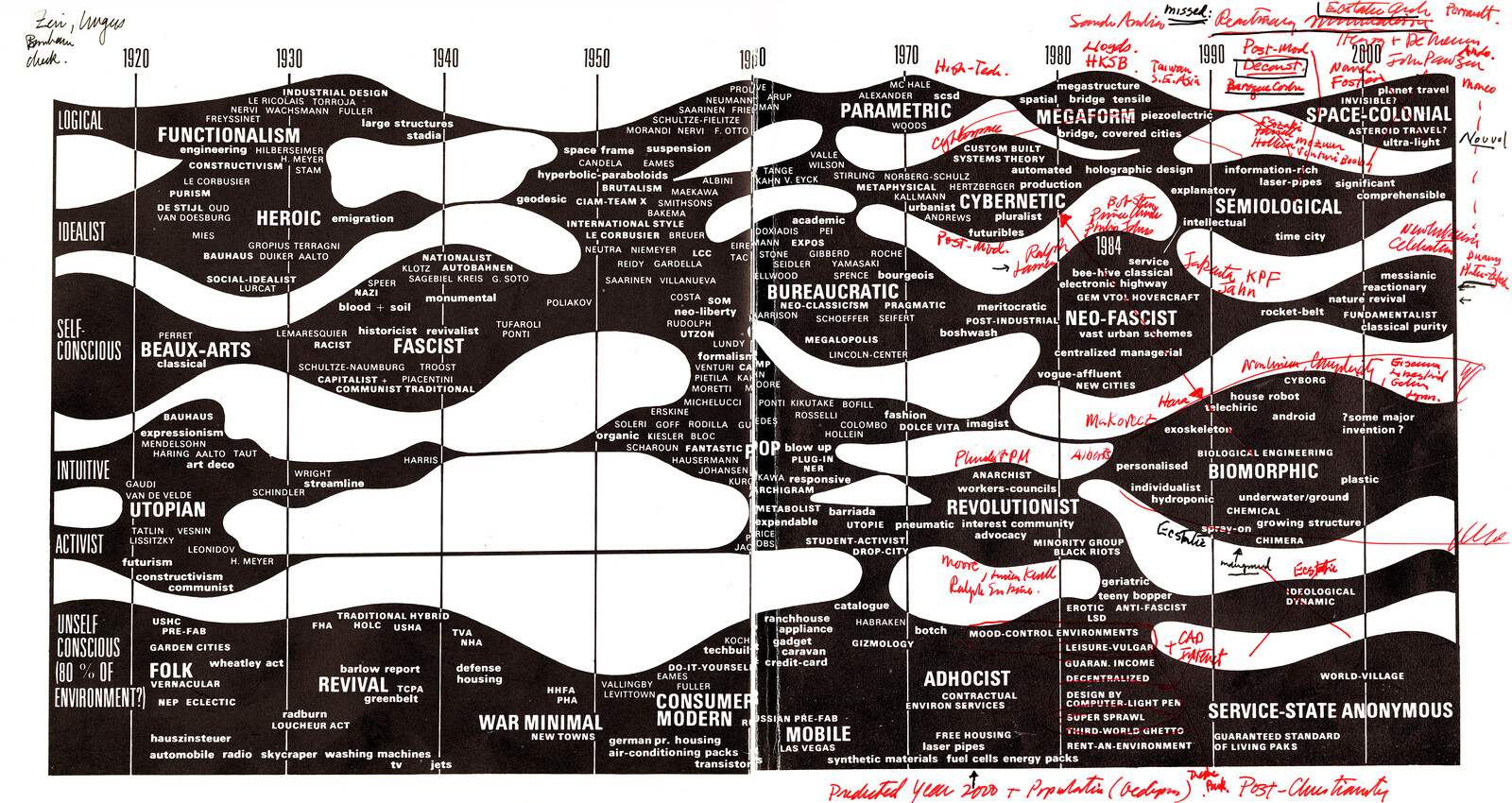

The words that populate the cross section of the present describe the underlying conditions that shape architecture. Architecture is Climate shatters any illusion of architecture as an autonomous discipline distanced from the world. While following Charles Jencks’s six horizontal bands, it moves away from his description of architecture as genealogies of individual architects. Climate breakdown operates at a societal and global level, and exceeds the influence and agency of any individual person or object. At the same time, it refutes any sense that hero figures can intervene and save us from disaster.

The Rifts

The pockets of white space in Jencks’s diagrams tempt being populated with an alternative history of architecture that falls outside of his persuasive worldview. These gaps have been interpreted here as vertical rifts that burst through the multiple sediments of exploitation, pollution, and crisis, creating new relationships with space, time, and work that undermine the violence of global capitalism. Critically gathering the past to project futures that move away from the status quo is paramount. Bursts of inspiration and hope exist in the gaps of the present. In these gaps, fragile formations are already emerging, which need support and bringing together to develop new spatial and social relations. While we cannot erase the bedrock, or foundations, upon which our present is built, we can tap pockets of pressure, resistance, and solidarity that lie within it. In this way we can to help construct architectures and climates that are fit for the future.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993).

This is the central argument driving Barnabas Calder, Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency (London: Pelican, 2021).

Amale Andraos, “What Does Climate Change? (For Architecture),” Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, ed. James Graham (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City / Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 297–303.

This phrase, of course, is a deliberate mis-phrasing of the black feminist writer Audre Lorde’s critique of white supremacist and patriarchal systems that govern everyday life. Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House (London: Penguin Classics, 2018).

Alexander von Humboldt, “Alles ist Wechselwirkung,” 1803. See ➝.

“When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters, with an imprudent precipitation, the springs are entirely dried up, or become less abundant. The beds of the rivers remaining dry during a part of the year, are converted into torrents, whenever great rains fall on the heights.” Humboldt, “A Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctal Regions of the New Continent,” 1814.

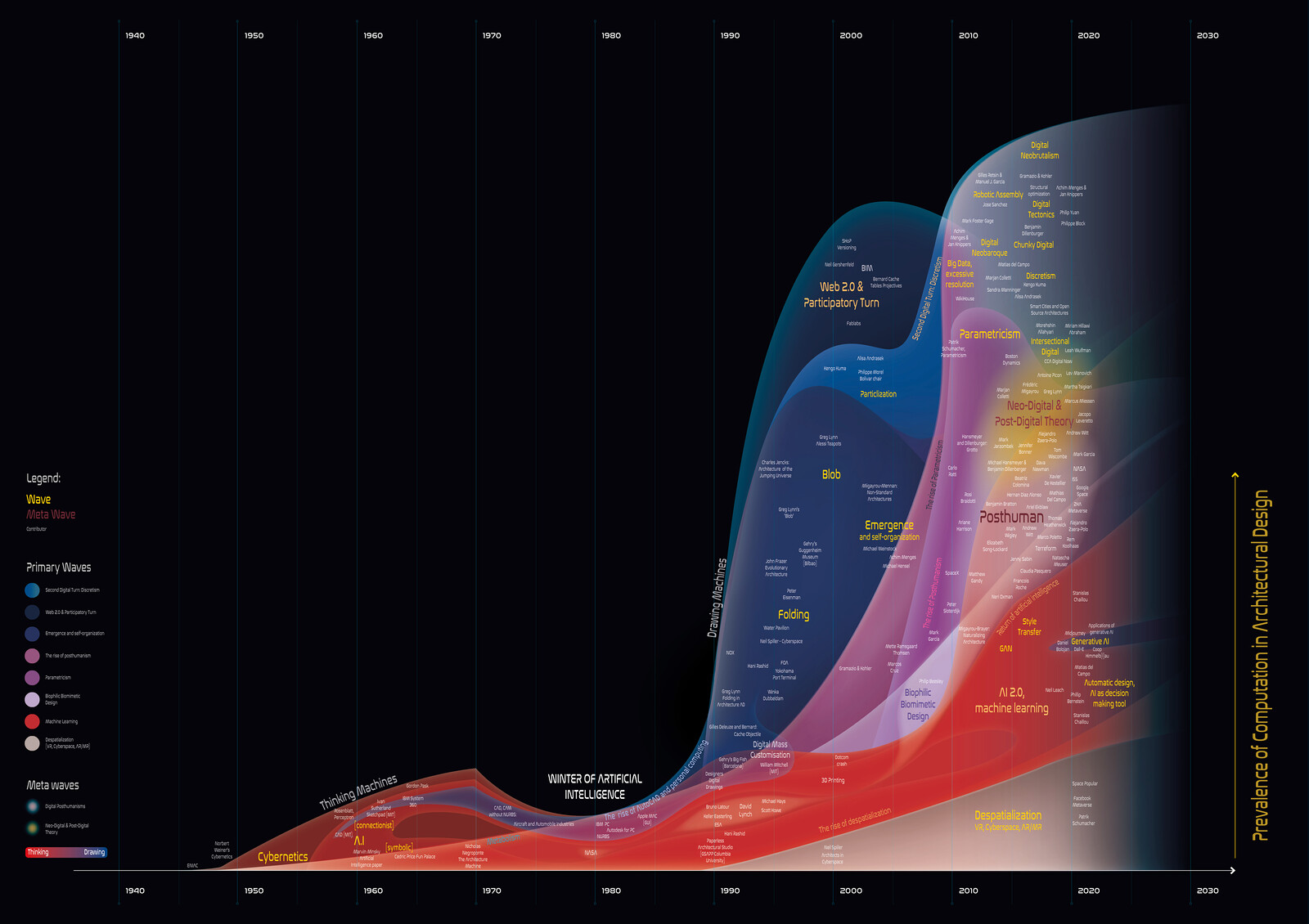

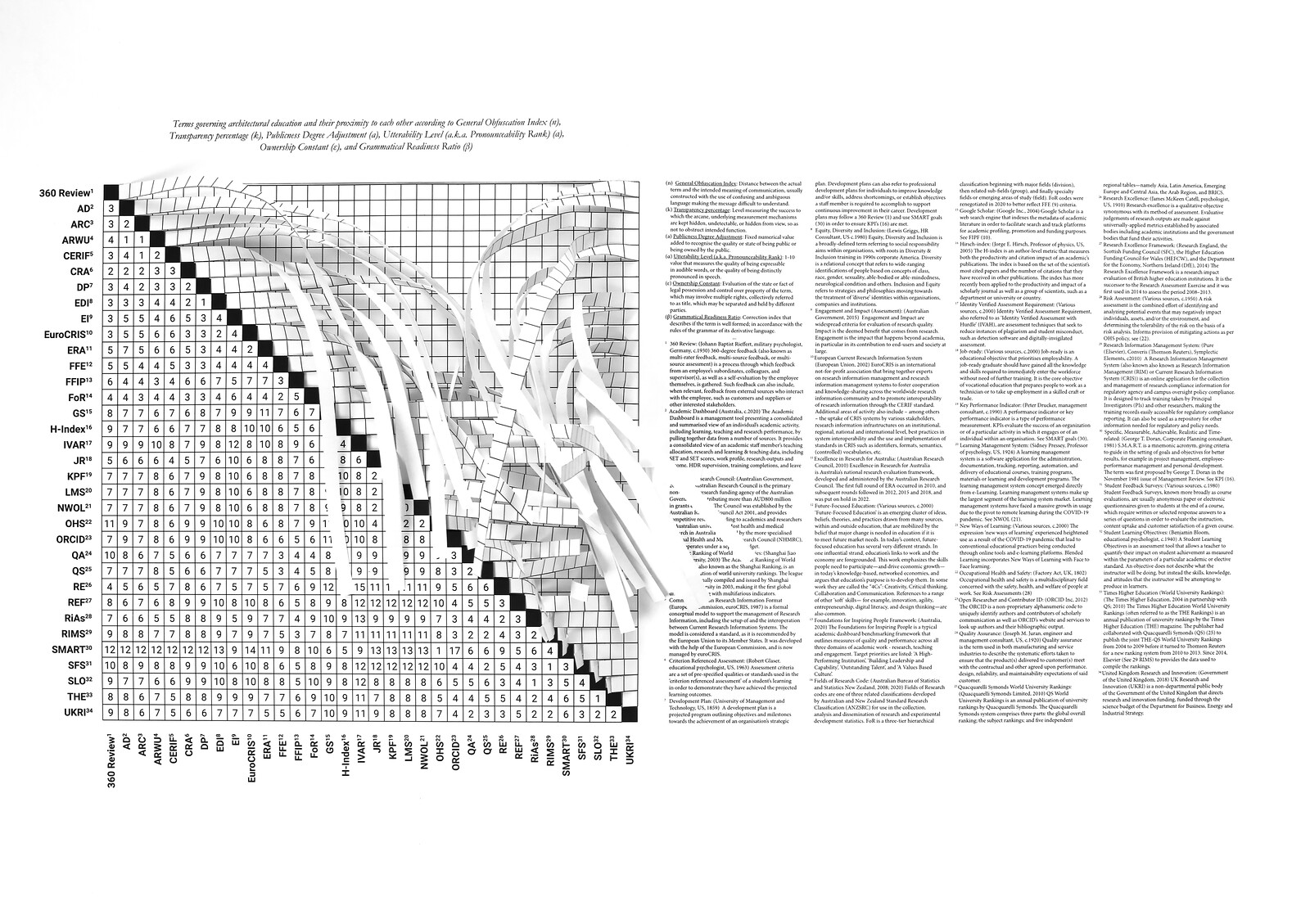

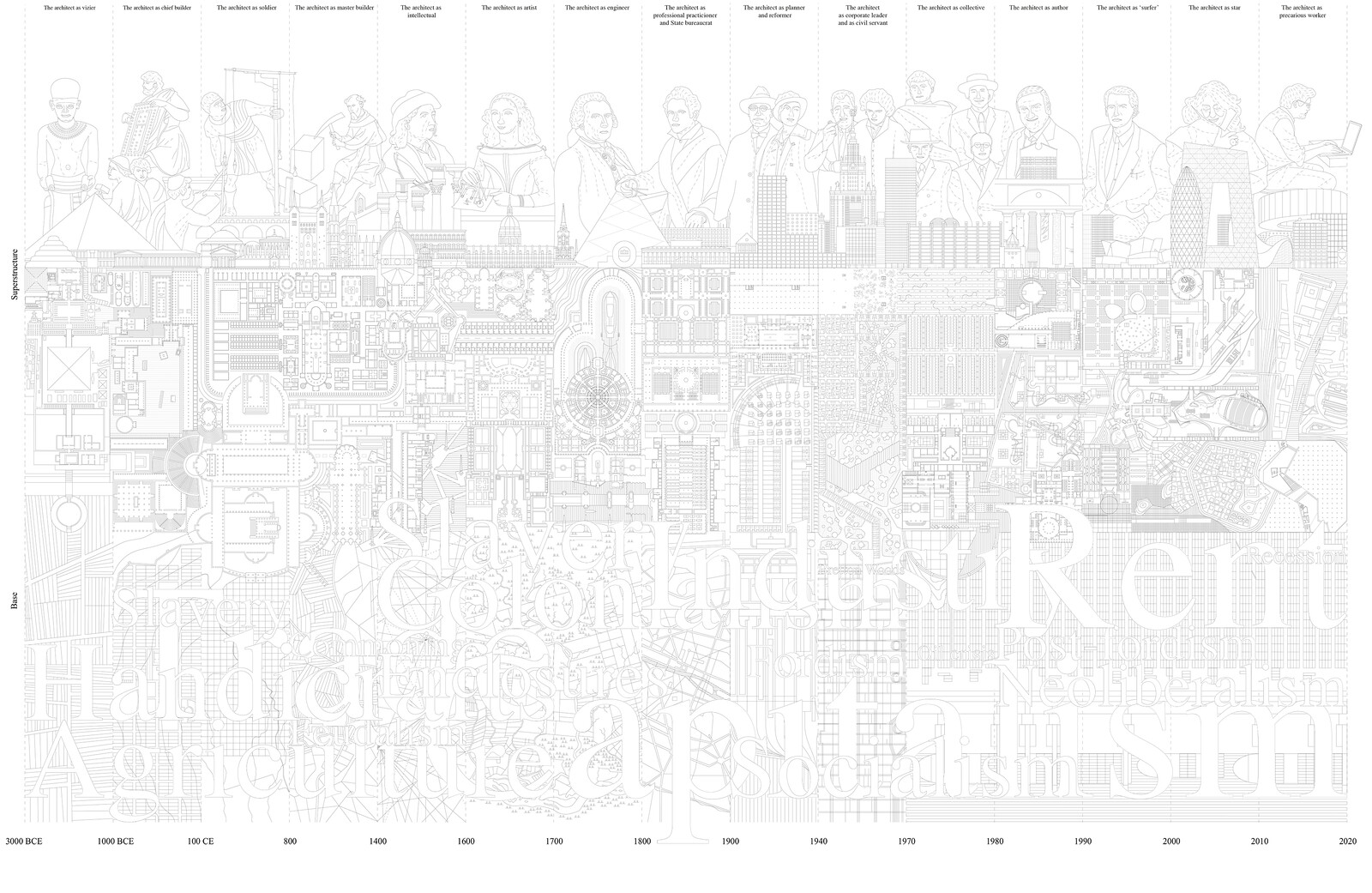

Chronograms of Architecture is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Jencks Foundation within the context of their research program “‘isms and ‘wasms.”