I was first introduced to P. Staff’s work via a pamphlet by Isabel Waidner, produced for their show “The Prince of Homburg” at Dundee Contemporary Arts in 2019. Recently out as trans, and isolated because of the pandemic, I became obsessed with the film at the center of the exhibition—a fraught dream sequence as experienced by the eponymous prince (taken from Heinrich von Kleist’s play) interspersed with interviews with contemporary trans scholars, activists, and artists—and how Staff’s disoriented, exhausted prince, sleepwalking his way to political martyrdom, could make sense of my own fear and exhaustion as reasonable responses to structural oppression. Having missed the show, I pieced it together from the commissioned texts and a few small images, and only later watched the film, when a friend gave me a bootleg copy on a USB alongside two works by Terre Thaemlitz. I remembered how I’d felt when I first encountered the work’s archive, but now I could also see its more hopeful proposition of dreaming as resistance.

Born in 1987, Staff’s work spans sculpture, performance, installation, and film: On Venus, shown at their 2019 show at the Serpentine, juxtaposed archival footage of industrial animal farming with a poem imagining life (impossible) on Venus, while Weed Killer (2017) explored the effects of chemotherapy drugs on the human body, interrogating the toxicity of survival. Staff’s films are dense and affective. Their visual intensity—often achieved through hallucinatory editing and shocking colors—seeps out of the screen and floods entire rooms and bodies. In Staff’s hands, film is a fully embodied medium. A structuralist filmmaker’s attention to materiality is refracted through minimalist installations which implicate the viewer’s body: liquids dripping into barrels from the Serpentine’s ceiling, protruding spikes with objects impaled, turning Dundee Contemporary Arts into a fortified castle. Yet Staff’s invocation of sensory overload and its weird, numbing relief can also be read through Maxi Wallenhorst’s description of dissociation as a trans style.

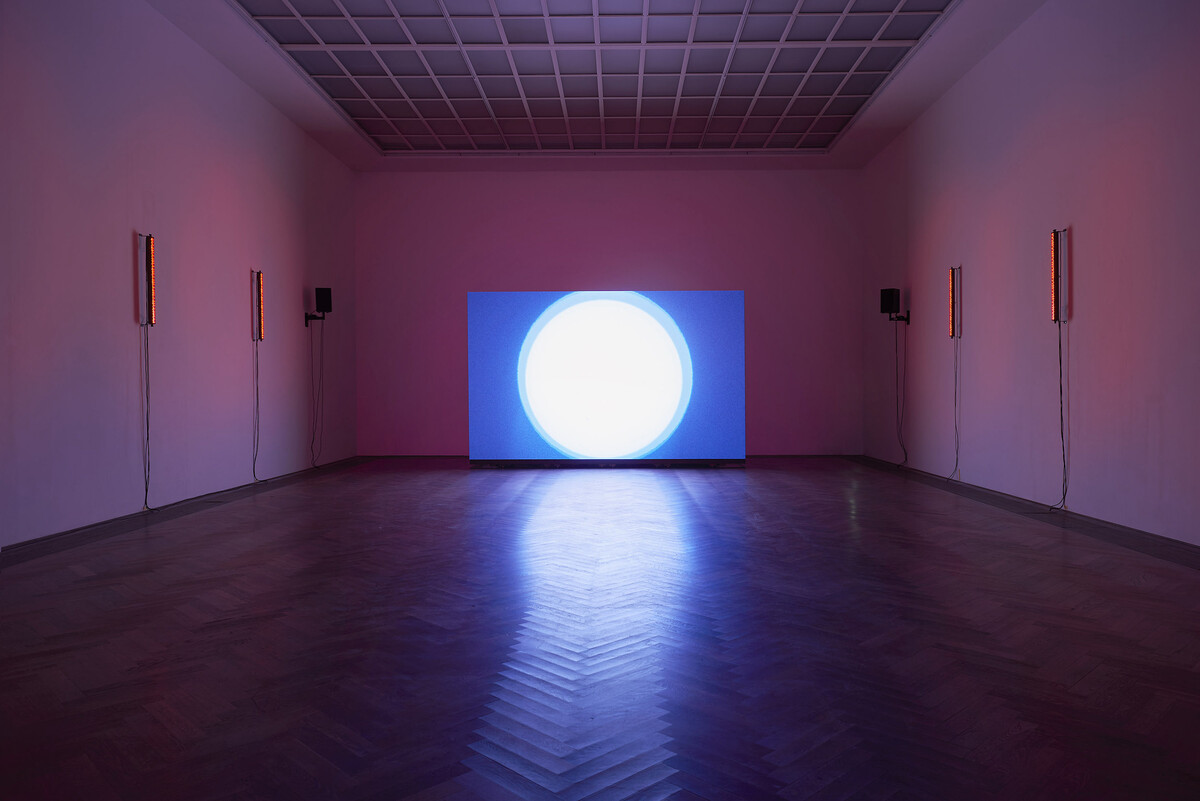

I spoke with Staff just after the opening of their show “In Ekstase” at Kunsthalle Basel. Their largest solo show to date, the works—a five-part holographic installation and a new film, La Nuit Américaine—reiterate many of the bad and trans feelings that first attracted me to their practice, helping me feel them as and alongside my own.

FRANCIS WHORRALL-CAMPBELL: Watching a bootleg copy of The Prince of Homburg was a very different experience to watching in a gallery: I realized that I was in a real-life replica of the world you were creating through the brutal architecture of the gallery installation. Now that we’re speaking just after you’ve opened a new exhibition in Basel, I wonder, how are you thinking about the experience you construct for visitors?

P. STAFF: It’s interesting that you saw The Prince of Homburg on a bootleg USB, because it’s the video that I’m the happiest might travel in that way. Partly because the work is so much about traveling, both physically and psychically, and also the limits of how far the body can go and what borders it encounters. Having said that, most of the time I’m aiming for a kind of hyper-specificity of context in my work. I want to seize the conditions as fully as possible.

With moving-image work, the assumption is that it’s infinitely mutable, that it could be endlessly reproduced on a phone or a computer screen or a projection or whatever. There’s something really thrilling about that, but like your USB stick, I think it’s more exciting when it’s counterfeit. When I am making an exhibition or a work, I’m often trying to push in the opposite direction, and really be specific with the light, temperature, the architecture, the feeling preceding or immediately after the experience. Do you walk out of a dark room and immediately go back into the light? Or is it a softer exit?

FWC: In the show, the viewer is led to the final film through four rooms, all of which create varying and intense bodily sensations through colored lighting, architectural features, and the holographic fans of the titular work. This feels very poised—both in the sense of confident (like a good top?) and delicately balanced. For example, one of the rooms is essentially a corridor illuminated with yellow light and netting strung just below the ceiling to lower it. Could you talk more about what you are hoping to achieve with the specific plays with space in this show?

PS: “In Ekstase” has a lot of spatial, architectural choreography. The show is constantly testing the sensation of putting the body of the viewer into proximity with volatile materials, volatile contexts, information that threatens somehow, light that burns.

I think of it as being a desire to heighten sensitivity, heighten sensation, and then sort of manipulate that sensitivity, you know? I’m just an incredibly sensitive person. I walk around feeling like a raw nerve, all the fucking time. And the shows are often just trying to kind of get at that feeling. Of course, I would be lying if I didn’t say, as an artist, there is something honed and precise and deliberate in how this is used. I’m attracted to how bringing sensitivity to the context of the institution renders it unstable.

Talking about the Basel show, I wanted it to feel like, the moment that you’re coming up on drugs and you don’t know if you’re up for it or not; the moment where pain and pleasure are collapsing into each other. Hysterical laughter bursting from sheer terror. It’s about an affective state, a contextual, linguistic, and conditional state of being. Understanding the work and exhibition-making in this way feels very trans and transed, but also wades into the kind of unpredictability of sensation: it defies specificity at the same time as being potentially deeply intimate.

FWC: That encounter with a bootleg of your work also brings up for me ideas of DIY transition and mutual aid. In this metaphor, your film is a resource (like black market hormones) handed round between friends. But I wonder if it’s more than a metaphor. Your installation Hormonal Fog (2020), made in collaboration with Candice Lin, emerges out of knowledge—largely lost or suppressed through colonialism—of the power of certain plants to chemically transform the body. In releasing a herbal vapor into the gallery space, the work promises the literal alteration of the viewer’s body. There is something so magical about this premise. Obviously, the installation doesn’t exactly work like this, but it is tantalizing! And it got me thinking, how can we collectively invert tools of control and brutalization to be tools of survival?

PS: What I appreciate in this question is that there’s something gleeful alongside something kind of threatening. Hormonal Fog came out of a moment when I was looking at black market hormones and informal hormone distribution networks, trying to track a bit of a lineage of mutual aid through queer healthcare in general. I had also been researching and making work on self-performed orchiectomies. I was also looking at information that was circulating very early on in the HIV and AIDS epidemic, in newsletters and round-robin letter exchanges. People were giving each other advice on how to tell— or conceal from—their doctors what they were experiencing, and critically, how to navigate, often duplicitously, the medical system of the time to gain access to specific courses of treatment.

This research threaded back to living in London at the beginning of the post-2008 “age of austerity.” It became increasingly common to hear friends give each other advice on how to navigate the dramatic changes in social structure, including, again, having to conceal information, exaggerate, or lie, or leave out certain facts to access something like housing or disability benefits. I should say that all of these strategies—horizontal mutual aid, the necessity to conceal, or lie, or mislead, or illegally trade— these are strategies for reclaiming power, and if not power then merely just fundamental dignity, from a hegemonic power that is deeply racist, homo- and transphobic, ableist and so on.

FWC: This is all such important context, and a reminder of the ways in which many of us have to subvert power in our everyday lives to get by. How does all this research make its way into the work?

PS: It is really multifaceted. Usually there is a bit more of a “seepage” of this research into my work, rather than perhaps the more direct or literal relation that is seen in Hormonal Fog. That work essentially takes research into the hormonal properties of herbalism and pumps it through a hacked fog machine (the kind used for Halloween parties, theatre productions, or raves) to disperse an endocrine-disrupting smoke or fog into the gallery.

But it’s one of those works where suddenly everyone’s feelings about hormones, pollution, and sexual stratification, all of that stuff, suddenly comes to the fore. Both Candice and I have been publicly and privately berated for that work, put in kind of hostile situations where people’s anxieties and anger around control suddenly come out. We have also both experienced people’s glee and optimism, wanting to lie underneath and be enveloped in it, huff on it, make their own, learn a recipe.

FWC: I appreciate what you’re saying about the work’s literalness. What I enjoy about the work is how it turns over the ways in which we’re non-consensually produced as cisgender, and then of course, as soon as someone attempts to non-consensually produce something other than that, everyone loses their shit.

PS: Exactly. Something you’re also circling around is that the work engages with a theatre of consent. I think most of us experienced this dramatically through Covid-19, and through the theatricalities of hygiene and consent around viruses and other pollutants. It is anxiety-inducing. Am I already full of microplastics? Can I really purify my tap water? Will leaving my packages in the mailbox for a week protect me from Covid? Candice and I were both excited by the ways endocrine disruption was perverting essentialist ideas around sex and reproduction. I think we could all be angry at the ways, as you say, we have been non-consensually produced as cis. But like any conversation around environmental harm it is unevenly distributed across race and class and geography. Hormonal Fog channels these complex, often contradicting forces, so I’m not surprised it is often met with feeling.

FWC: I was reading an essay by Johanna Hedva about your 2020 show “On Venus” at the Serpentine in London, in which they write about being “irradiated” by the film’s brutal images, as much as the yellow light that flooded the gallery—yellow being, as Hedva notes, the color of arsenic as much as the sun. The similitude of poison and cure reappears in your film Weed Killer, which details the effects of chemotherapy on a cancer patient. What is it about that ambiguous affective state that interests you?

PS: In my work, I am trying to articulate a particular sense of being that, for me, begins with dysphoria, begins with the dysphoric condition as a way of understanding how you move through the world. To circle back to sensitivity, something I talked about a lot with Elena Filipovic, director and curator at the Kunsthalle Basel was, what could possibly be more horrific than just the sun rising and setting every day? What could ever be more terrifying than that? In this, I was trying to articulate how a veil of normality could be the most desirable and most terrifying thing possible. I identify with Lauren Berlant’s lack of interest in criticizing how and what people desire; instead, I try to understand it, or get at some sense of the seepage of desires—not to just question or overturn a desire for normality, sovereignty, that sort of thing, but to really feel it, to really fucking feel the complex, contingent ideas of living. And so I’m interested in the ways dysphoria, debility, inclusion and exclusion, liberation and oppression may operate, order, and structure our “lived” experience.

FWC: I read this in relation to what Eric Stanley identifies in Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonism and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (2021) about the paradox of LGBTQI+ inclusion in the state. Depending on a proximity to whiteness and property, sectors of the queer population are sold access to more and more rights as a means of liberation, at the cost of those who are beyond the still-intact limits of acceptability. I suppose I’m interested in how you respond to this prompt in relation to your work? But also this ambiguous political space that trans/queer people find ourselves in, marking the border between inside and out of state reach, feels similar to a set of phrases that I have seen you repeat—near-death, non-death, non-life— which also appear like border territories. What is the role of this line for you?

PS: The show “On Venus” was a lot about my anger at the UK, specifically England. Having a show in London, in the Serpentine, in Hyde Park; these are all significant layers. It’s funny because people said that the show was really empty and quiet, but it came from a place of real anger. Part of it was taking something as innocuous as sunlight and curdling it, making it acrid, as a way of gesturing towards an all-consuming, absolutely normal, violence. In some ways it also came from an anger around my own transness. There’s a term that comes from family therapy, the “identified patient,” which is a clinical term used to describe one person in a dysfunctional family who is used as an expression of the family’s inner conflicts. I wanted to turn my body inside out and say, dysphoria is everywhere. It is the most obvious condition. The clinical origin of dysphoria actually refers to a consistent sense of grief, and I often feel that grief is the primary affective model that I’m working in.

FWC: In the introductory text to the new show in Basel, viewers are promised a “weaving of trans poetics, mysticism and necropolitics.” I think we’ve covered the last of that triad—but I’m curious what trans poetics means to you?

PS: Poetry doesn’t, or simply can’t, replace political action, but it can do something else urgent. It goes places that politics can’t, it kind of embodies, lives, and moves. It moves quite gleefully, like we said earlier, and also promiscuously into those realms. And if we think of poetry as a world-making practice, making tangible our imagining of other ways of being, then transness inhabits a very particular space within it.

Something that we’ve been talking about for a long time in trans circles is the way that bodily autonomy sits at the nexus of a lot of issues in the West right now. In the UK, it feels like we’re at this point where agency, autonomy, and self-identification are suddenly (or, once again) at the crossroads for race, borders, empire, capital. And so to understand the political imperative of what transness is doing right now alongside the capacities of poetry, I think that’s why the phrase “trans poetics” ended up working its way into the text you’re referring to.

I love Maxi’s assertion that the dissociative style is an archive of not feeling. I’ve been talking a lot about this sense of the veil of normality, dissociative violence, mediated living. But it’s taken me a long time, on a personal level, to find my way back to something that I have always felt, which is that experimentation, or poetics, or incoherency is a political imperative. It’s a position that got kind of beaten out of me at art school, the ability to hold space for a kind of experimental, incoherent promiscuity. It’s been a long process of finding my way back to being able to claim that space again. It’s taken me a long time to get back to being able to say there is mysticism, there is poetics, there are also moments of unmediated feeling in the work.

FWC: If we are going to think about feelings and the body, I’m curious about the title “In Ekstase,” with all its invocations of good (possibly chemically-induced) feelings.

PS: Knowing that the show was going to be, first of all, in the Swiss context, there’s a nice porousness in the title. “In Ekstase” works in French, German, English. There are shifts in the spelling, but you’re always getting to the same place phonetically. I love the connotation of transcendence, the double pun of chemically induced pleasure too. The title has casual, promiscuous references to Simone Weil, Georges Bataille, Forrest Bess. In Ekstase is this beautiful place of losing control, becoming other, not-I. It felt nice to put my fingers into all of those wounds with the title.

The film in the final room of the show is called La Nuit Américaine (2023). The title refers to the name of the film technique we used, which is an analogue process of producing an image of the night from natural daylight. It’s a technique that was made in American cinema, and so outside of America, it was called the American night. I wanted to channel the collapse of day into night, the possible ensuing collapse of reason, of borders, of civility. Achille Mbembe uses the nighttime as a framework to describe the paradox of the postcolonial; the creep of fascism in liberal democracies a “nocturnal feeling.” Temporal rupture offers the possibility of innumerable futures. I am not necessarily an optimist, but I am addicted to possibility.

P. Staff’s “In Ekstase” is on view at the Kunsthalle Basel through September 10.