Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

September 26, 2023 – Review

Billy Bultheel and James Richards’s “Workers in Song”

Kirsty Bell

“Workers in Song” inverts the current artworld logic of exhibitions augmented by performance programs, and instead positions the live event as the centerpiece and the exhibition its supplement (some of the performance elements, along with a soundtrack, remain on show at WIELS until October 8.) Borrowing their title from a Leonard Cohen song, Belgian composer Billy Bultheel and Welsh artist James Richards staged a collaboration that examines the elasticity of such live events, questioning the relations of appropriated artifacts (poems, films, artworks) to newly constructed material (collaborative videos, sound, banners), of spoken word to music or imagery, and of live performance to pre-recording, thus the very nature of liveness itself.

It takes place in an exhibition room sparsely adorned with banners, rudimentary props (folding chairs, desk, piano), and two large screens hanging opposite each other. Four angled bleachers sit the audience “in-the-round.” A reperformance of Ian White’s Ibiza (2010) is the first of a nine-part program that is dense, heady, jarring, tender, anxiety-inducing, and shot through with moments of beauty and pathos. Liveness was central to the late artist and curator White’s thinking: he saw the rehearsed gesture and performer’s presence as a “false promise” of the live, finding liveness …

September 23, 2021 – Review

Brussels Gallery Weekend

Vivian Sky Rehberg

Having moved to “the capital of Europe” just last August, I approached the 14th edition of Brussels Gallery Weekend (BGW) aiming not to reckon with changes in the city’s cultural landscape, or discern the features of a much-touted “new normal,” but to focus on the present. I started with “Generation Brussels,” an exhibition of young Brussels-based artists without gallery representation, sponsored by BGW since 2018. Spread across two venues, the thematic focal points this year were gender, identity, space, and environment. In their curatorial statement, Dagmar Dirkx and Zeynep Kubat declared individualism dead, lauded collaboration, and opposed binary divisions (nature/culture, artist/curator, etc.). This overly familiar discourse and thematic framework belied the curators’ sensitivity in arranging a true medley of mixed-media installations, videos, photographs, and textile works, many of which seem to have been produced with the strictest economy of means.

Amongst these, at the Tour à Plomb sports and culture center, Günbike Erdemir’s ramshackle burlap tent At the horizon of the evening of no return (2020) arose from the ground floor like some arcane pagan shelter, eerily lit and replete with small paintings of fantastical creatures and ritualistic scenes, pillows, and wooden bookstands built for reading on the floor. Upstairs, …

November 4, 2016 – Review

Haseeb Ahmed’s “Wird”

Mihnea Mircan

The inauguration of the European Parliament building in Brussels was marred by a defect of architectural planning: visitors approaching it were blown over by currents of air inexpertly funneled around the construction. One imagines stacks of European bureaucracy sent into elegant airborne swirls by the gusts of wind. The front of the building was fitted in 2008 with a “comfort ring” that alleviated the wind nuisance, a solution designed and tested at the Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics, a NATO research facility near Brussels.

This was one of the many narrative threads woven by artist Haseeb Ahmed into a performance presented earlier this year at the institute. Ahmed’s exhibition at Harlan Levey Projects realigns the documents, artifacts, and intuitions of that event, with the film The Wind Egg (2016) the most explicit link between these chapters in his research. Footage of the performance is edited into the fictional survey of a regular day’s work at the institute. The audience that followed the performative procession through wind tunnels, the auscultation of their inhuman breath, is now out of sight, and the scientists attend to arcane contraptions, moving between what seem to be an aviary and heavily equipped chambers of impregnation, mythopoeic …

October 22, 2015 – Review

Manon de Boer, “On a Warm Day in July”

María Palacios Cruz

Manon de Boer’s minimalist cinema is at its most radical in her latest film On a Warm Day in July (2015), currently on view at Jan Mot, Brussels. Like a number of her films made over the past ten years, it features a performance—American Soprano Claron McFadden improvises on a seventeenth-century song in the empty ground floor of a Brussels townhouse. In previous works by de Boer, such as one, two, many (2012), Dissonant (2010), or Presto, Perfect Sound (2006), the performer is at the center of the film’s concept, and at the center of the camera’s attention, but in On a Warm Day in July the camera quickly abandons the singer and goes on to wander and explore her surroundings. Void of objects, the space is filled with history, each crack on the wall or scrap of detaching wallpaper a mesmerizing cinematic presence.

In de Boer’s work there is often an evacuation of the visual image, giving way to the prominence of the soundtrack and/or voiceover. The filmmaker is consistently interested in unsettling the traditional hierarchy of image over sound, exploring the disjunctures between sound and image that are characteristic of cinematic modernity. Such is the case in her first …

March 5, 2015 – Review

David Panos’s "The Dark Pool"

Mihnea Mircan

A “dark pool” is a form of high-speed trading whose machinations take place outside the reach, and modicum of control, of regular markets. But rather than indict a hypertensive and extra-judicial financial system, David Panos’s “The Dark Pool” is concerned with a different set of transactions, binding labor and the labors of the image in our accelerated times. In contrast to the promises of personal emancipation and reconfigured communality that accompany progressively ethereal ways of being in the world, immaterial labor here is weighed down, mattered and gestured. It is embodied in figures that complicate the distinctions between abstraction and representation.

Video works, accompanied by sculptures that coagulate objects and ghostly images into the appearance of three-dimensional film stills undo the standard take on abstraction as a toolbox for comprehension of—or a scenography for ethical reconciliation with—the world. Panos’s investigation into abstraction seems to be, to equal extents, a historical critique and a taxidermic operation: it introduces detours into the chronology of philosophical maneuvers via which thought disincarnates and wrests intelligibility from matter; complementarily, it stuffs concepts with the material ballasts they sought to discard in order to be concepts and attain metaphorical lift-off from mundane, unholy realities. In “The Dark …

January 21, 2015 – Review

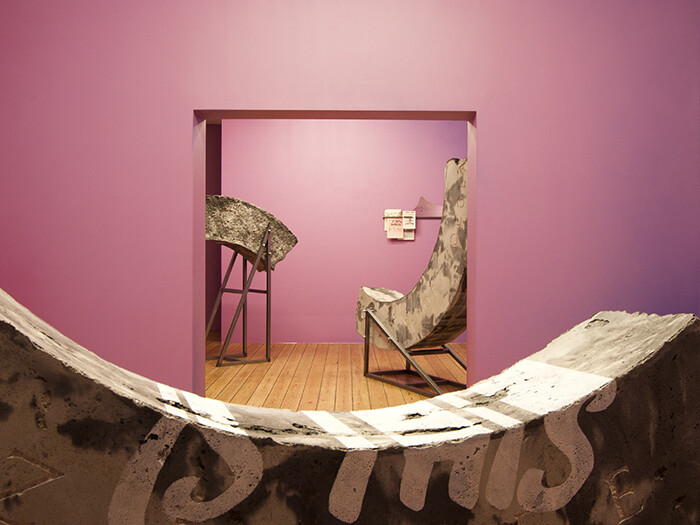

Ivan Argote’s "Reddish Blue"

Adam Kleinman

The archive is dated; we now live in the age of footnoted fictions, as artists, writers, politicians, and technocrats each try to shape political reality through semi-plausible myths… each “based on a true story.” As such, it might be time to start weighing the techniques of Hito Steyerl, or Ben Lerner’s speculative political fictions that change the world “depending on its arrangement into one narrative or another” against the not dissimilar disinformation tactics of political theater found in say, Putin’s éminence grise, Vladislav Surkov, and his use of multiple false flag operators to confuse any cogent narrative of so-called “reality.” For this review, let’s take Ivan Argote’s “Reddish Blue” as the opening salvo for this discussion.

As the title suggests, the exhibition is based on the color purple, and several of the gallery walls are painted appropriately. To learn why, visitors are presented with a slideshow that apes PowerPoint and silent movies by projecting 80 expository intertitles. It begins, “I think it’s true…” and from there, a series of narratives that may or may not be true follow. These accounts more or less intertwine as the artist uses anecdotes to tell personal and familial histories, but the crux of it all …

July 4, 2014 – Review

David Lamelas’s “Mon Amour. Reading Films”

Dessislava Dimova

On the way to David Lamelas’s latest show, which inaugurates Jan Mot’s new location in Brussels, I wondered how much of an artist’s practice is trapped in the discourses surrounding its inception. After all, aren’t artworks entangled with, if not contingent upon, the conditions that govern the time of their creation? In particular, I was thinking of those proponents of Conceptual art, who simultaneously created their own discourse. Does the language of Conceptual art have a fixed temporality? If so, what is it? Is it still evolving with the changing times or is it doomed to remain forever in a fixed historical category?

Perhaps my thoughts were influenced by Mot’s decision to open his new space with an austere, conceptually driven exhibition that so perfectly represents the spirit of his program. (Isn’t supporting Conceptual art an old Belgian affair, taken up brilliantly by the gallery into its many afterlives today?) Or maybe it was the uncanny experience of finding myself in a maison de maître in the distinguished Rue de la Régence, a location that has just surfaced as a hub for several galleries, instead of the messy downtown corner where Mot’s white cube previously resided. This change not only marks …

January 13, 2014 – Review

Eric Baudelaire’s “The Anabasis & The Ugly One”

Adam Kleinman

Inverting the specters of progress in his 2005 Le Siècle, Alain Badiou revisited the decade-long about-face of a Greek mercenary force that successfully fought its way home from a failed, early-fourth-century incursion in Persia. He did this as a means of determining where a sequacious political left stands today, and towards which it should, or could, move in the turmoil of apparently lost or fragmented causes. Awareness of this infamous military campaign of ancient Greece—and its internal political make-up as a mobile, democratic collective in retreat—reaches us today by way of Xenophon (c. 430–354 BC), a soldier and writer among its ranks who mediated the wayward expedition in his multi-volume work, Anabasis. With more than a wink to Badiou—and to poet Paul Celan, who marshaled the anabasis as a symbol of a lived caesura—artist Eric Baudelaire has intertwined two recent personal and revolutionary narratives in his film The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shingenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years Without Images (2011). Reflecting on a number of stalled revolts in Japan and the Levant region, as well as their more recent outcomes, the film concerns the history of May [Mei] Shigenobu, the daughter of militant Japanese Red Army (JRA) co-founder …

November 6, 2013 – Review

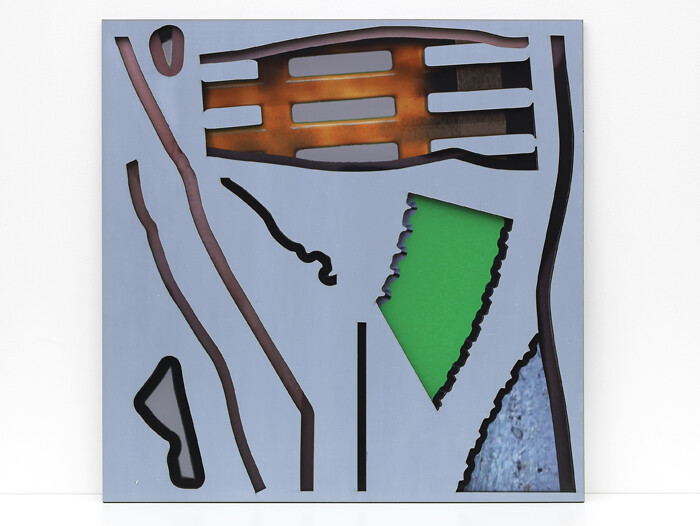

Jimmie Durham’s “Works of Science and Yellowness”

Nav Haq

Jimmie Durham has had a significant presence in the Low Countries of late with a major survey (co-curated by Bart De Baere and Anders Kreuger) in 2012 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (M HKA) in Antwerp, as well as a solo exhibition at De Vleeshal in Middelburg earlier this year. For this reason, a third monographic presentation of his work within such a short timeframe might not seem particularly urgent. However, given the curiously distorted sense of scale that people have in this part of the world, many art lovers rarely take it upon themselves to travel the relatively short distances between Belgian cities. Durham’s exhibition also marks the inauguration of Galerie Michel Rein’s new space in Brussels, who like numerous dealers, has been attracted by the recent developments of the European capital’s art scene. In reality, the artistic potential of the city remains largely open and unresolved, leaving a number of expectations as yet to be fulfilled.

The gallery space, and thus the exhibition, is relatively modest in size, but this is not too much of an issue, as it brings together three sculptural works and five drawings rather neatly into a formal unity. With an opportunity for more …

April 19, 2013 – Review

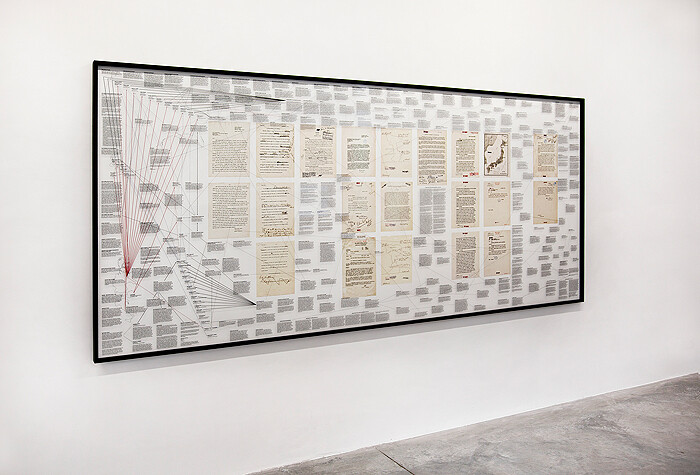

Gert Jan Kocken’s “But We Cannot Speak about the Atoms in Ordinary Language”

Adam Kleinman

After Hiroshima, after Chernobyl, after Fukushima, it is time, once again, to speak about atoms. However, the title of Gert Jan Kocken’s Spartan yet powerful exhibition teases us with another question: what language shall we use, and how will such a choice temper or frame the conversation? Although the title is borrowed from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Werner Heisenberg, Kocken appears to be interested not only in a review of scientific thought, but moreover, how tangential elements are stratified into the language of written history. Spinning out intricate allusions to split-mentalities and motives with various chains of actions and reactions into the essential structuring device, the artist advances his telling in the exhibition’s centerpiece, Fission (2013).

Fittingly, Fission presents two twinned, yet fractured “infospheres” united under a larger glass window. The first are a group of reproduced declassified political dispatches, which justify the American dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, while the second depicts the massive networks, discoveries, and communications required to develop the American, German, and Soviet nuclear programs respectively through the use of linked captions printed directly onto the glass. Although the work takes the appearance of a giant flowchart, the choice of information and its placement …

December 17, 2012 – Review

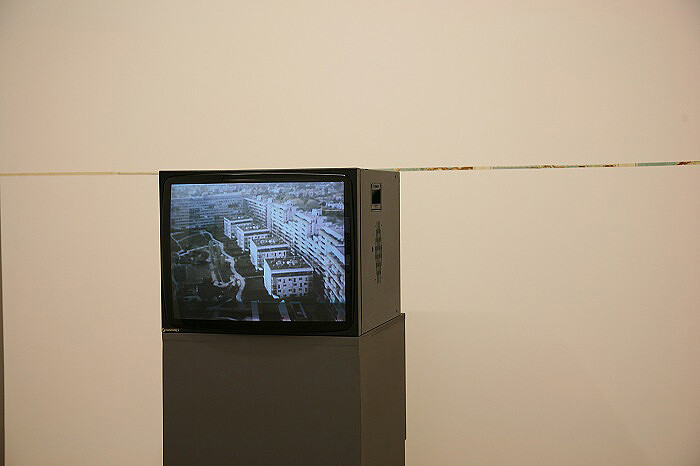

Mona Vătămanu & Florin Tudor’s “Geometric Analogies”

Natasha Ginwala

An anti-censorship quote from the first century claims that when paper burns the words fly away. But what happens when the paper itself is granted flight? In the film Manifestul (Manifesto, 2005) a hand appears from the edge of a balcony and releases a cluster of pages. They swirl about, filling the frame as a breeze forms an accidental background score. Several of Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor’s films, including this one, are made at an in-between time—neither day nor night—but a gray hour that holds the cinematic image in a state of aporia. It is in this suspended space that temporal gestures find grounding and a certain materiality—be it in the carrying of dust (Praful / The Dust, 2006), covering the floor of an exhibition space with rust (The Path / Rust Ingots, 2009), or the painting of revolutionary scenes as acts of remembrance (the series “Appointment with History”).

Vătămanu and Tudor invent vulnerable architectures that draw upon the violently fragmented modernism of post-socialist Romania. Their articulations of loss within Ceaușescu’s dictatorship are conceived in conversation with places and things as “survivors” of history. However, rather than inhabiting chronological pathways, the artists’ works serve as a rehearsal ad infinitum.

Manifestul …

September 24, 2012 – Review

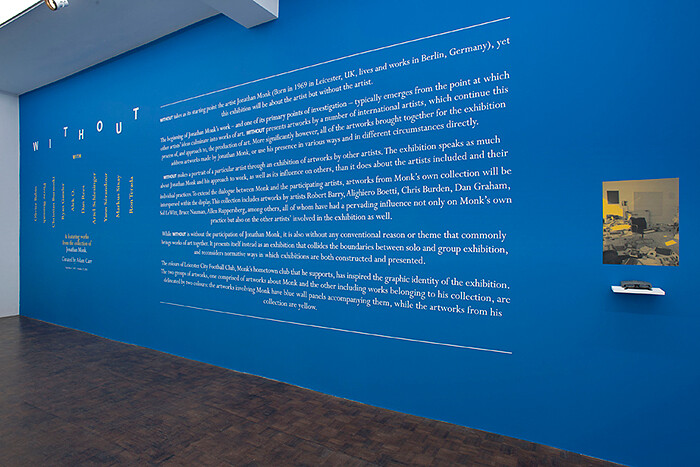

"Without (Jonathan Monk)"

Matteo Lucchetti

With Olivier Babin, Pierre Bismuth, Christian Burnoski, Ryan Gander, Alex O., Dan Rees, Ariel Schlesinger, Yann Sérandour, Markus Sixay, Ron Terada, & works from the collection of Jonathan Monk

In Ecce Bombo, a cult, late-70s movie by Nanni Moretti, there is an iconic scene in which the protagonist, Moretti himself, is on his way to a party. He calls a friend and asks: “Will I draw more attention to myself if I actually come to the party and spend all night in a corner, or if I don’t show up at all?” If Jonathan Monk were Moretti and the party in question were the exhibition “Without (Jonathan Monk),” the answer would be clear: by not participating in the show at all, Monk definitely stood out more than if he had actually been present.

At first glance, the curatorial structure dictated by the proclaimed non-appearance of an artist reminded me of the last Istanbul Biennial, in which curators Jens Hoffmann and Adriano Pedrosa wove together a group show that ultimately created an innovative retrospective of Felix Gonzales-Torres without there being a single work of his on view. But the connections between these two shows stop there, not only because Monk is very much …

July 5, 2012 – Review

Kelley Walker

Maaike Lauwaert

“It’s not easy being green.” To some, this line will evoke the Apple commercial showing a camera circling the new (green) iMac against a white background. Through the green plastic one could see part of the inside of the computer, and the sad voice of Kermit the Frog slowly pulling your heartstrings: “When I think it could be nicer being red or yellow or gold.” The commercial communicates simplicity and minimalism with a song that has a funny rapport with the color of the machine. It’s a prime example of the style first used in 1959 by the agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) who quite literally revolutionized the world of advertising with their campaign for selling the Volkswagen Beetle in the US. Not an easy job if you think about how the Beetle was designed in Nazi Germany, how the timing was more than a little off (so soon after the war), especially considering that this was the heyday of big cars that exuded luxury.

The campaign DDB devised for the only economy car on the US market at that time was groundbreaking in many ways. Using black and white photography and depicting only the image of the car, the happy …

January 19, 2012 – Review

Allan Sekula’s “Polonia and …”

Jian-Xing Too

Allan Sekula’s exhibition “Polonia and …” opens with a new piece, Europa (2011). Hung on a dark pink wall, Europa shows a man trying to sleep on a long narrow baseboard heater at the foot of a glass wall in Charles de Gaulle airport. A difficult balancing act, three of his limbs tentatively rest on a slightly higher cable railing and a low metal barrier that protects the heater from being bumped by luggage carts. Stemming from a desperate search for warmth and constrained by airport architectural details, his bodily posture uncannily resembles the pose of Titian’s Europa (in The Rape of Europa, 1562) being carried off by Zeus disguised as a bull. Rather than replicating the latter’s dynamic diagonal composition, this Europa lies as horizontally within the picture plane as does Walker Evan’s sleeper-cum-unemployed-drifter on South Street in his American Photographs. Indeed, instead of being transported by a divine force, Sekula’s Europa is paralyzed by economic forces. Nothing is less certain about the open market of today’s European Union than its promise of mobility.

One wouldn’t delve into such a reading of this single image if it weren’t for its title and the fourteen photographs and two quotes—selected from the …

March 15, 2011 – Review

Joachim Koester’s “I myself am only a receiving apparatus” at Jan Mot, Brussels

Vivian Sky Rehberg

In the darkened gallery, two projectors, each threaded with a black-and-white 16mm film by Joachim Koester, cast twin beams of light on two whisper thin screens sandwiched between them. The screens are suspended back to back on taut wires and seem to float in midair. The room purrs and hums moodily; the mechanical apparatuses squat there, arcane and totemic. Pushing through the heavy curtain at the entrance, you have the distinct sensation that you are interrupting a private conversation—but the films are silent. The only thing interrupted is the flow of time.

Koester’s films I myself am only a receiving apparatus (2010) and To navigate, in a genuine way, in the unknown necessitates an attitude of daring, but not one of recklessness (2009) both feature actor and poet Morten Soekilde. It’s a decision that creates the illusion of the simplest temporal and narrative links between them: first the man does this, then he does that. The former shows Soekilde in the reconstruction of Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau (1923-1937) at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover. Koester tightly frames the warped and faceted interior, dulling sharp edges in a soft chiaroscuro that flattens the three-dimensional space into an abstract tableau punctuated with a few …

Load more