In the landscape that is gradually emerging, it’s not so fantastical to imagine the eventual replacement of all international exhibitions with beer festivals, local food and craft fairs, or other types of events that reaffirm a particular identity and sense of belonging, rather than offering an encounter with something or someone outside of that tightly constructed place. It’s also becoming possible to imagine a reduction or even a termination of human movement: from the reemergence and fortification of numerous national borders, to increasing visa restrictions and the exclusion of entire religions or nationalities from entering certain countries, to perhaps requiring a permit to leave. I grew up in the Soviet Union and I do remember living in a regime under which you can’t leave the country without permission from the state.

In one of his treatises, Malevich writes about the difference between artists and physicians or engineers. If somebody becomes ill, they call a physician to regain their health. And if a machine is broken, an engineer is called to make it function again. But when it comes to artists, they are not interested in improvement and healing: the artist is interested in the image of illness and dysfunction. This does not mean that healing and repair are futile or should not be practiced. It only means that art has a different goal than social engineering.

As a settler-colonist, it’s important to consume—to develop … consummate taste … a taste for the other, for the unknown, for the new. It’s important to consume Art … Art, especially the kind conjuring nostalgic memories, can relax you, can lubricate your voyage back toward a primal confidence, to your intuition, to your privilege, to your influence, to be influenced.

With the assistance of a brilliant Wakandan engineer (let’s say T’Challa’s sister Shuri), one entrepreneur develops a process that can manufacture two spears in one hour. This advancement will shake up the whole spear industry because this entrepreneur can do in one hour what the others do in two. This advantage and its market consequences has a name. It’s called relative surplus value. What happens next? The factory that makes two spears in one hour moves forward in time; that is where the extra value is. It moves toward a society that has yet to exist. This society does not have as yet its culturally necessary labor time set to two spears in one hour. This factory is then, for a moment, the future of its culture. But eventually, the other spear entrepreneurs figure out how to make two spears in one hour, and so two spears in one hour becomes the new culturally necessary labor time. Then one day, an entrepreneur applies some science to spear production. This new kind of spear can fire beams of concentrated energy. All the warriors want this spear. The market is shaken up again. For a time, the entrepreneur enjoys relative surplus value, but from the consumer end of the market.

Art after culture. Just to say the simplest and most obvious thing: culture, in the broadest sense of the word, is good at pointing to things and naming them, but not so good at describing relationships between things. It privileges declarations, right answers, universals, and elementary particles. It is captivated by circular logics and modernist scripts that celebrate freedom and transcendent newness—narrative arcs that bend toward a utopian or dystopian ultimate.

Forty years ago, I remember shouting, “No future! No future!” with some young British musicians. I thought it was the provocation of an unlikely avant-garde. Now, everybody thinks that the future is over; now, the sentiment aligns with a conformist position held by most of humankind. “No future” has become common sense, and this is why cynicism is expanding in contemporary culture, in contemporary political behavior. Futurism was the expression of a society that expected something from the future, and of a society that truly felt the warmth of community, whether encapsulated in the nation, the family, or social ties to working communities. All the above was the reality of lived experience a hundred years ago. No more! Today, the nation is a nonexistent thing. The dissolution of the nation is an effect of the pervasive digitalization of information and of power based on information. Do you think that Google belongs to the United States? Not at all. The United States belongs to the territory of Google. So does Italy, and France, and so on.

Along with being an index of democracy, art is also a lucrative niche for the global entertainment business. Art has thus become a form of consumable merchandise, destined to be used up. In this situation (diagnosed by Arendt and others in the 1960s), artists have either embraced this quality of art as merchandise (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst), or rejected it in the name of politicization and criticality (Hans Haacke, Andrea Fraser, Hito Steyerl). With globalization, critical artists have been summoned to become useful by surrendering art’s (always partial) autonomy and taking up the task of restoring what has been broken by the system. So they denounce globalization’s collateral damage and contemporary art’s woeful conditions of production. They imagine a more just future, produce political imaginaries, disseminate counter-information, restore social links, gather and archive documents and traces for the “duty of memory,” etc. Perhaps, then, the prior role of the artist as a cultural vanguard has given way to a mandate to cultivate a feeling of political responsibility in spectators, in the name of self-representation and the representation of Enlightenment values.

Artists are a symptom of the high regard that is placed on absolute trash these days. It’s the people who encourage and sanction the exhibiting of this garbage that we blame. We wouldn’t let them whitewash the outhouse. This and similar art represents all that is bad and is nothing more than The Emperors New Clothes. Historians say art reflects the culture of its people. This so called ‘art’ to our mind is totally despairing to any advancement and enlightenment of the human race. If this is a reflection of our present day culture, we really are in trouble. We spent a considerable amount of time and effort trying to ‘understand’ art. It was quite a miserable experience, because we felt really thick and stupid; because we couldn’t for the life of us see what was good about any of it. Then one day it just struck us that absolutely all modern art is simply worthless. Personally we wouldn’t walk to the end of the street to look at this trash.

Our most ancient animal ancestor, Dickinsonia costata, is categorically lodged between pestilence and creature. Or rather, Dickinsonia dithers in a space betwixt bacteria and animalia. Let us accept that our beginnings find us plunked down in the center of the margin. She, a flat mat, possesses an expanding physical symmetry. Some bugs are fugitive like this; see how they slide under your domestic things. Yet her remains are found as fossils on remote Russian cliffs. Her gravesite overlooks a marginal sea, a part of the warming Arctic Ocean—a site of intense oil and gas speculation. The slightest psychedelic tendency urges me to bypass my oral and historic memory and uncover an otherworldly and cellular memory of Dickinsonia costata: “Mama!?” I lisp.

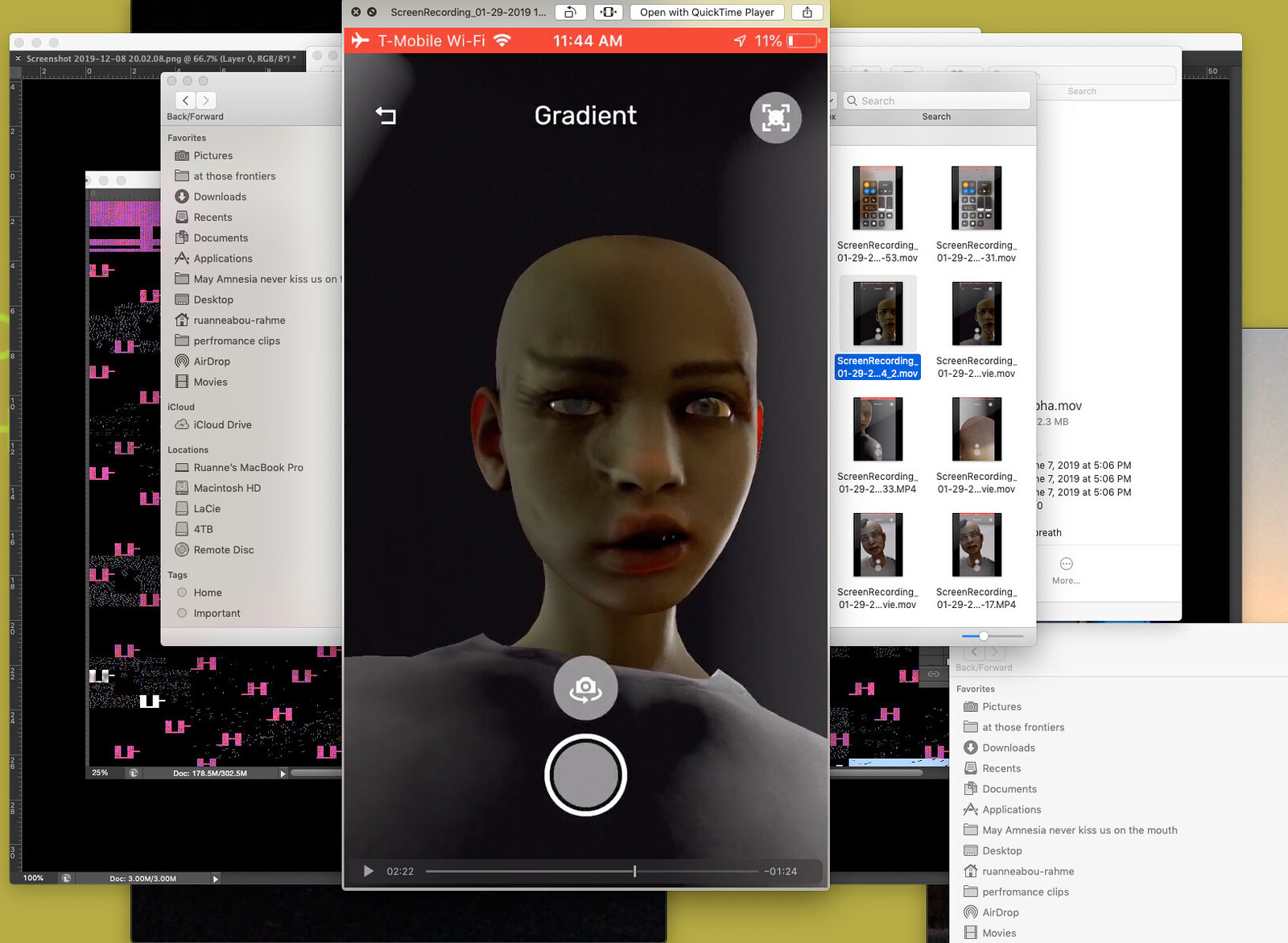

Fragments from Edwards Said’s most personal and poetic work, After the Last Sky, are repurposed to create a new script that reflects on what it means now to be constructed as an “illegal” person, body, or entity. The script is turned into a song that is sung by the artists as multiple avatars. Created via a software program that generates avatars from a single image, the avatars in the video all come from images of people who participated in the “Great March of Return” that continues to take place regularly on the seamline in Gaza, an area that has been under physical siege since 2006. The relationship between fugitivity, fragility, and futurity becomes manifest in this field. The project uses low-resolution images that were circulated online; the avatar software renders the missing data and information in the original images as scars, glitches, and incomplete features on the characters’ faces.