“The war in the Persian Gulf ended just three months ago,” the New York Times alerted its readers in May 1991, “but some museums are already collecting artifacts from the conflict.”1 Spooky spolia from America’s “first” Iraq campaign—such as Barbara Bush’s fatigue jacket or cookies found in discarded Iraqi uniforms—were making their way to assorted US military and state museums for public display. The objects said this is what we did, but these cast-offs of imperial plunder came also to be wrapped in revisionist identitarian empathy for the plunderers. The Times quotes a Smithsonian curator proudly proclaiming, “If you had come to this museum in 1960, it was essentially a white, elitist story. We have tried to convey that this is a much more complicated, much different story. Just as we have George Washington’s uniform, we want to have uniforms of a sergeant from a tank unit.”2

In the aftermath of Operation Desert Storm, Allan Sekula described that asymmetrical liberal empathy surrounding the first American war in Iraq as a selective mathematics of “innumerable third world bodies” and “precisely enumerated first world bodies.”3 But today’s theater of American exhibition-making flips these terms: precisely enumerated “others” counterpose innumerable masters lost in the fog of American regret. This reversal is characteristic of the empathetic errand of “unstrangering” foundational to modern humanitarianism and American counterinsurgency alike, for it drives the motor of military domination by juicing it culturally.4 Though it verges on the paranoid, this is one way a visitor to “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” might have understood how the curators at MoMA PS1—the Museum of Modern Art’s affiliate in Queens, New York, where the exhibition was on display from November 2019 to early March 2020—came to deck their galleries with so many “hearts and minds”: artistic victims, witnesses, and far-flung observers of endless (Iraq) war.

We empathize with our imagined visitor’s paranoia. While the exhibition tinged its titular historical event with a generic humanist regret for its toll, it all took place, after all, in an institution at whose organizational summit sits a certain Leon Black—billionaire investor, Iraq war profiteer, and chairman of the MoMA board. (While PS1 began as an independent institution in 1971, it was acquired by MoMA in 2000.5) Black is the founder and CEO of the private equity firm Apollo Global Management (named for a god the Greeks called Ἀλεξίκακος—Alexicacus, “averter of evil”). He has profited from the Iraq campaign through Apollo’s ownership of a grim menagerie of private military contractors, including the civilian-murder outfit formerly known as Blackwater. And Black’s connection to US war-making in Iraq doesn’t stop there. On the board of Apollo sits A. B. Krongard, the executive director of the Central Intelligence Agency during the run-up to the 2003 ground invasion of Iraq. (Krongard was responsible for the CIA’s initial hiring of Blackwater under a lucrative Afghanistan contract in 2002; he was repaid in turn when Blackwater’s then-owner Erik Prince asked him to join its board in 2007; and he quickly vacated his Blackwater board seat under subsequent conflict-of-interest scrutiny.6) Further, the exhibition thanks and features works lent by the person who has overseen the Iraqi national pavilion at the Venice Biennale since 2013, Tamara Chalabi, scion and on-the-ground accomplice of a crucial CIA-funded “native” asset in that invasion, Ahmed Chalabi.7 One could go on.

Count on us for the vulgar tally: Three hundred artworks from around eighty artists; two curators (Peter Eleey and Ruba Katrib); one exhibition (“Theater of Operations”) about a twenty-year period (1991–2011) understood to represent the historical frame of the Iraq wars, occupying all three floors of MoMA PS1. One billionaire MoMA board chairman (Leon Black); nine formerly separate private military contractors rolled into a conglomerate (Constellis) now owned by Black’s Apollo Global Management; seventeen Iraqi civilians murdered in the infamous Nisour Square massacre of 2007, perpetrated by mercenaries employed by Blackwater—a company that is now part of Constellis8 (and that was twice renamed after said murders “tarnished its brand”); one million overall civilian deaths (too many to rebrand).

First the inventory, then the self-accounting. Near the beginning of their catalog, the exhibition’s cocurators, Eleey and Katrib, explain: “The artworks brought together here convey experiences and positions that counter the essentializing tendencies of mainstream narratives, particularly those that seek to define certain people as the ‘enemy’ and attempt to place them beyond the reach of our empathy.”9 Soon this revisionist empathy cracks up: Eleey, in his longer essay later in the catalog, self-critically hedges that framing Iraqi artistic production “through the reductive lenses of violence and victimhood” might be counterproductive. Delirious acrobatics follow: “In assembling this exhibition, we worked with an awareness of these distorting pressures of reception, undoubtedly reinforced some of their political deformations, which must also be understood to have affected Western artists, albeit differently.”10

How to address an exhibition that professes to “counter … mainstream narratives,” then refuses to construct an organizing counter-narrative of its own, then admits that its reckoning—“undoubtedly”—made things worse? One could say that the exhibition’s contortionist contrition itself sounds a lot like the current “mainstream narratives” of the Iraq wars, in which critical-historical accounting for cause and effect is voided by a scattershot plurality of times and places, people and events, stories and mediations. Curatorially evacuated of historical and institutional consciousness, “Theater of Operations” has a posthistorical event par excellence—the titular “Gulf Wars 1991–2011”—come home to roost at the posthistorical museum.11

“Rather than reducing this complex subject into a linear trajectory,” PS1 director Kate Fowle explains in her foreword to the catalog, “Theater of Operations offers a range of responses made in the context of two US-led wars in Iraq.”12 That much is clear, more or less—the two-wars narrative, as her colleagues acknowledge in their essays, is a fabulation of the public-relations apparatus of endless war. But there’s a linear trajectory right there in the exhibition title—a chronology, perhaps even a period—that the actual exhibition shirks at every turn. This failed historical burden comes into view earlier in the same foreword, when Fowle gives three examples of similar exhibitions that “foregrounded this institution’s commitment to such historical presentations”: “EXPO 1” (2013); “Stalin’s Choice: Soviet Socialist Realism 1932–1956” (1993); and “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994” (2002). Fowle was right to group them, since they all represent different reactions to the historical subjects of the posthistorical museum: the first exhibition by moving toward the futural mode of “speculation” (the house style of posthistorical historicism); the second through rote semi-triumphalist nostalgia toward the aesthetically and politically defeated; and the last, organized by the late Okwui Enwezor (it traveled to PS1), through a valiant postcolonial resuscitation of the task of critical periodization.13

Instead of critical periodization, “Theater of Operations” punts the Gulf Wars in favor of a grab bag of poorly articulated “stories” resolving to an underlying curatorial ethos of confused regret, a self-flagellating self-congratulation. It mirrors the lack of serious investigation into the Gulf Wars by most American left-liberals, who either believed that they “should not have happened” or simply withdrew rather than tangle deeply with the reality and spread of their ongoing repercussions. When it came time for the New York Times to cover the exhibition, arts writer Jason Farago decided to forego a traditional review and instead printed a “conversation” with a former Times Baghdad bureau chief.14 The latter wondered, after seeing the exhibition, “what contemporary art in Iraq might have looked like” if the wars hadn’t taken place. (Never mind that the Times had stenographed the case for war to its credulous readers.) This exculpatory counterfactual speaks to the logic of identification and identity at the center of this show’s morbid humanitarianism: Iraqis are indelibly marked by the travesty we have made of their country, but their ethical nobility consists purely in their impossible resilience to this mark we made. Our greatest form of empathetic identification, then, is to spare them in retroaction, un-marking them as we un-mark ourselves. The only form of identification ultimately imaginable is for “us” to hold out for Iraqis the image we hold of ourselves: we, the shifty half of aggressor and aggressed—guilty, maybe, but whole and holier for it.

The loose suggestion of the exhibition’s central historical conceit—that it produces a kind of Iraqi art history—is undercut by the cluttered and forced juxtaposition of artworks made by so-called “Western” and “non-Western” artists and the modish refusal to chronologize or even synthesize these contents spatially as an event-driven transnational history. Neither the physical arrangements nor accompanying texts do much to examine Iraq’s deep and deeply scattered modes of artistic production. In this, “Theater of Operations” reenacts that most tedious trope of postcolonial critique: the West as concept, the East as content.

In the rare moments where the show promises to narrate an Iraqi art history worth considering, as in Shakir Hassan Al Said’s extraordinary twinned paintings Fragmentation No. 1 and Wall #1, both from 1991, the wall texts do little to explain how they fit into the histories to which they allude. To wit: “Al Said’s works provide a crucial point of reference for many of the artists in Theater of Operations, who have looked to him as a leading advocate for the establishment of abstraction as a key strategy in Iraqi art.” This is a surprisingly important sentence to find secreted away in the middle of a small paragraph in a remote gallery on the exhibition’s second floor, and odder still that these paintings are installed next to Paul Chan’s 2003 video Baghdad in No Particular Order, a work whose appearance here might perhaps be best explained by applying its title to the curatorial method of “Theater of Operations.” Al Said’s work, like the Iraqi art history of which it is a part, cannot and should not be understood within the singular framework of war, even and especially as staged in the unexamined frame of institutions, like PS1 or the Iraq pavilion in Venice, whose conditions of existence abutt and abetted that war.

At the level of layout and content, the show itself was garlanded by 24/7 distraction, with cable television anachronized as material and medium, a kind of Internet 1.0: the oversized Necklace, CNN, a self-explanatory 2002 sculpture by Thomas Hirschhorn, was installed alone in the gallery opposite the building’s entrance. Hirschhorn’s gold-foil-enrobed links teased the sequence of large projections that patterned the rest of the exhibition’s ground floor, where video works by Monira Al Qadiri (Behind the Sun, 2013) and Michel Auder (Gulf War TV War, 1991/2017) framed the exhibition’s first impression with the grainy spectacle of cable B-roll, blown up beyond the scale of even the biggest-screen TV, curatorially montaged into canonical media works from Harun Farocki and Dara Birnbaum, among others. And there are many others. It is as if, since the Gulf Wars began some decades ago, there has been no examination that might compel the show to update either its media-theoretical determinism or clash-of-civilizations historicism, evident in lame distributions of passive and active agency: East/West, viewer/soldier, Iraqi/non-Iraqi. The wars were not even enacted by a strictly geographic “West.” The first Gulf War was largely funded by Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. (The 2003 invasion and subsequent regional wars were made possible by Qatar’s Al Udeid Air Base, which remains the largest US base in the region.) Many of the artists in the show have lived outside of Iraq, in “the West,” for almost the entirety of their formation and career, again blurring the curatorial vulgarism of identity.

The purpose of the show was, ostensibly, to examine “the legacies of these conflicts beginning with the Gulf War in 1991, featuring over 300 works by more than 80 artists based in Iraq and its diasporas, as well as those responding to the war from the West.”15 As laudable and relevant as this may be, the exhibition overdetermines the legacy of the wars (or was it “conflicts”?) by pinning it all on the screen, as if to say it was the media, stupid! A selection from Jean Baudrillard’s “Gulf War” writings is the exhibition catalogue’s first outside text, appearing sandwiched between essays by the show’s two curators. The first Gulf War’s televisual, more-than-real mediation was infamously figured as noneventfulness by Baudrillard, who also wrote that Western audiences all live “in a uniform shameful indifference.”16 But the idea that millions of citizens were simply slackjawed out of historical consciousness by CNN soothsayers oversimplifies a much more enduring passivity, if not complicity, in ongoing massacres in Iraq that remain on display. As nicely packaged a theory as the medium it aims to critique, the delirium of cable news did not exactly spirit away our ability to confront his guerre du Golfe, nor fast-forward its brutal body count. The stupor was not alchemically induced but somehow willed.

Moreover, the exhibition’s swerve to telecommunicative mediation seems at cross-purposes with its desire to foreground work by “Iraqi” artists. This appears to suggest that the civilian on the ground in Iraq was inaccessible to American audiences as an ethical subject at the time, justifying the exhibition’s concern with artistic practice as a kind of belated humanization. Artists in Iraq, particularly young artists who came of age during the invasion, have never lacked the desire or ability to create art. But globally visible contemporary art, as anyone in the field knows, often assumes a ladder of prestigious art-school attendance, production support, mentorship, residencies, international travel, and social skill, usually in English. At Iraq’s two main art schools in Baghdad, which are free of cost, middle- and working-class students hardly have access to resources reserved for elites. Instead of journalists speculating what Iraqi art could have looked like—or curators failing to engage with artists outside their comfort class—it would be more useful to consider how actually-existing forms of production could be supported and understood. Young Iraqi artists never stopped working, and are informed—formally and informally—by the extensive visual and political histories that stretch from the Sumerian era to Baghdad’s current sprawling metropolis. Which “Iraq” is ultimately being recuperated in this exhibition?

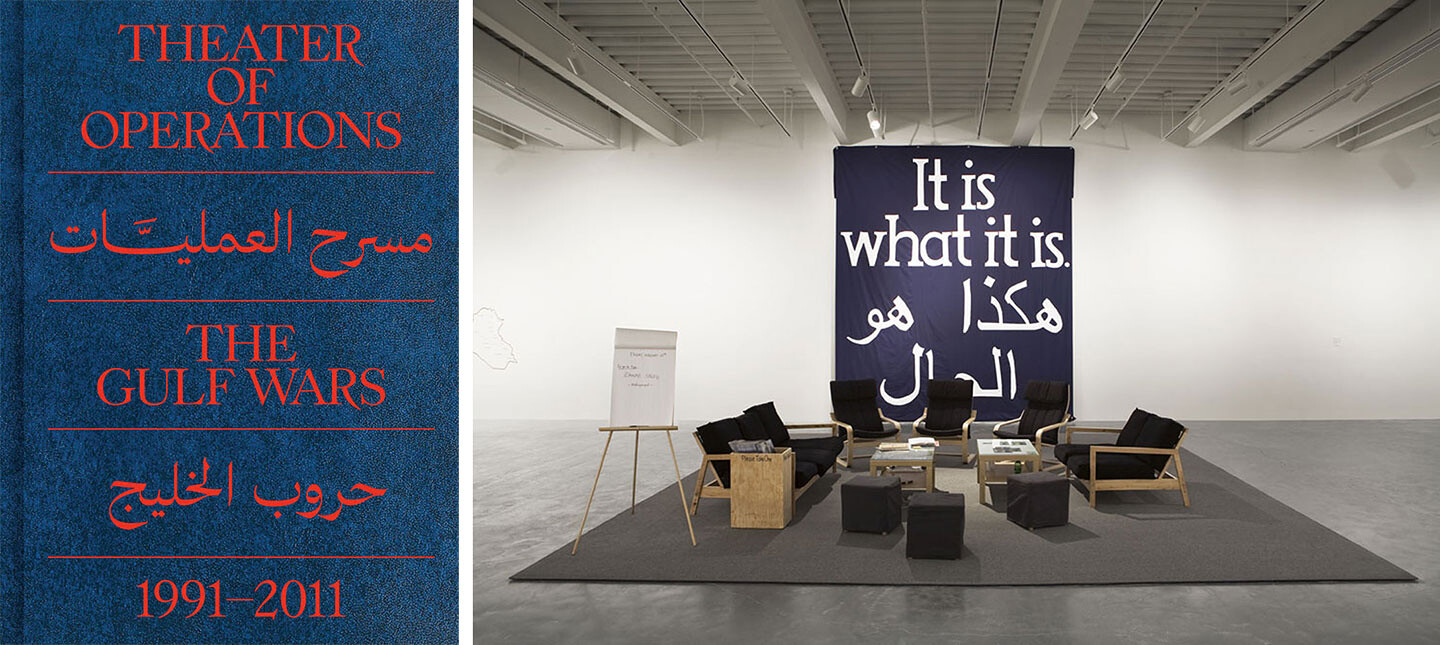

Left: Cover of the catalog for “Theater of Operations” (MoMA PS1, 2019). Right: Jeremy Deller, It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq, 2008, exhibition view at New Museum, New York.

One of these is that of big-budget American films like Jarhead (2005) and Hurt Locker (2008). These Hollywood dramas exhibit Iraqis as an enemy staged prophylactically against sympathetic and identifiable American forces, though this extends even to Werner Herzog’s Lessons of Darkness (1992), which was screened on both the opening and the closing days of the PS1 show. It applies as well to Jeremy Deller’s It Is What It Is (2009) videos, also screened for the show; these videos are part of a larger artwork that included an American PSYOPS officer, an American curator, an Iraqi military translator newly arrived to the US, and Deller himself in an all-male traveling crew of supposedly “non-biased” experts on Iraq and/or the art of conversation.17 (The translational gimmick of the “Theater of Operations” catalog cover calls back to a banner Deller produced, its theater of Arabic script curtaining the untranslated English of its contents.) Along with the film screenings, the exhibition included works by artists Steve Mumford and Francis Alÿs, the former embedded with US troops (2003–11), the latter embedded with Kurdish forces in a 2016 commission by the aforementioned Tamara Chalabi’s Ruya Foundation.18 “It Is Still Ongoing” is the title of a catalog essay by one of the exhibition’s curators, prompting one to imagine that the contextualization of Iraq’s ongoing violence has in fact been subversively understood. Instead, here the curators rehabilitate Iraq’s pop-military narration and similarly constructed artistic theater.

Fixed squarely inside this exhibition is the assumption that Iraqis should be grateful for an American institution of note finally acknowledging these wars, however superficial this acknowledgment might be. Yet the violence of these wars lives irrevocably on inside the US and its “coalition partners,” and addressing that is hardly a benevolent act. Perhaps worst of all for a contemporary art institution, the attempt to generalize and pluralize the theme of a brutal and ongoing campaign of terror resulted in an exhibition that precisely mirrors the crux of the problem when it comes to US thinking on Iraq: it is not rooted in any substantial understanding or attempt to address the complexity of Iraqi experience. Iraqis inside Iraq are today revolting against the iterative “theaters of operations” that have taken their voices and their lives and all but canceled their future. They are—remarkably, and historically—resisting with their own protests and artworks. And these protests have no inroads into “Theater of Operations” at PS1 because the exhibition—outside of profiteering board members—does not communicate, in any way, with Baghdad.

The cost of the exhibition’s incapacity to stage a historically situated claim to artistic production around the Gulf Wars, and the inevitable contradictions of its institutional linkages to American capital (and therefore American war), was perhaps most evident in its alienated and alienating treatment of the only two artists in the show who had any recent residence in Baghdad, Ali Eyal (b. 1994) and Ali Yass (b. 1992). Yass, currently living as a refugee in Berlin, planned to use proxies to intentionally tear his work on display at the show—childhood sketches that comprised 1992; Now, (2016–17)—on the final day of the exhibition. Conceived as a protest against the museum’s silence regarding Black’s position on its board, Yass’s action was unauthorized, unlike several other politically flavored—and officially sactioned—interventions on the exhibition’s public program of “performances.”19 This kind of reactive antagonism toward the institution has long been accepted as a part of the officially unofficial culture of artistic discourse, an artistic “right” of which MoMA has a long history and to which Yass alluded in his own explanation.20 But here PS1 felt threatened by this insubordination, summarily deinstalling his work prior to the last day of the exhibition and making the rare decision to escalate the presence of private security guards by calling in armed police to the gallery in which Yass had choreographed an activist group (MoMA Divest) to express his artistic position.21

NYPD at the MoMA Divest protest at PS1, March 1, 2020. Photo: MoMA Divest.

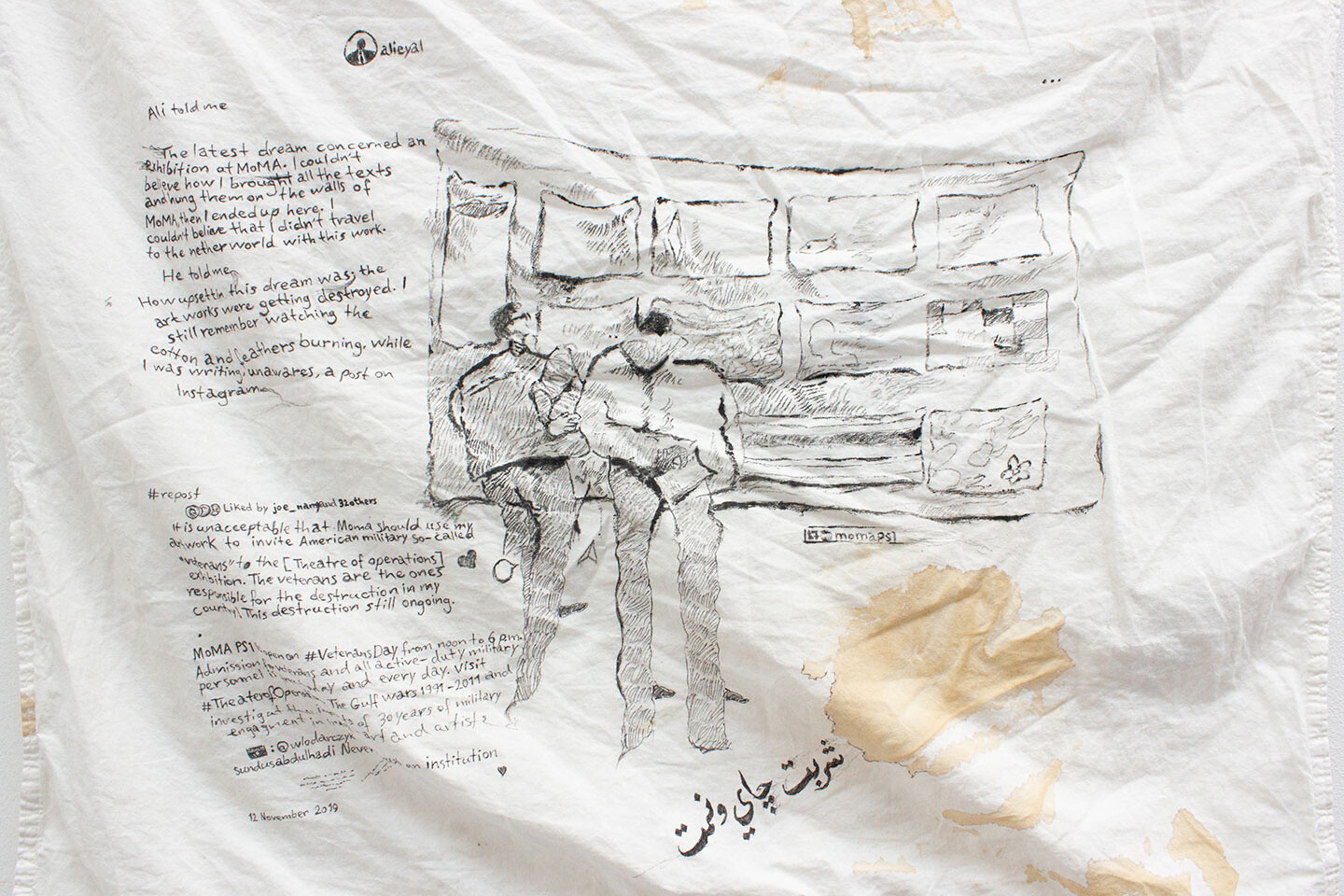

Eyal, for his part, discovered that an image of his work from the show, Painting Size 80x60cm (2018), was being used on social media by PS1 to advertise free admission for military veterans on the American holiday Veteran’s Day. The work is comprised of pillowcases on which the artist has drawn illustrations and writing in Arabic, recounting the dreams of the members of an Iraqi family who have lost loved ones in the war. These acts of alternative memorialization are part of an ongoing series. The museum, which does not own Eyal’s work and did not remunerate him (or any other artist) for participating in the exhibition, had not sought permission to use his artwork in this way. Eyal later produced a new pillowcase work on the “nightmare” of having his art cater to “the ones responsible for the destruction in my country.” In his youth he had experienced American soldiers as a violent occupying force, abusing civilians in his neighborhood and invading the home he shared with his mother south of Baghdad. In their above-quoted preface, the curators toggle conceptually and grammatically between objects (“artworks”) and subjects (“certain people,” i.e., Iraqis). These objects are subject-oriented: according to the curators, the exhibition of the former is meant to produce “empathy” for the latter. A paradox of autonomy, because those to whom “empathy” is due (“certain people”) are, of course, also producing artworks for their exhibition.

Ali Eyal, Nightmare, 2020. Black ink on pillowcase. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Diana Cantarey.

On the exhibition’s opening day last November, Constellis posted a job listing for a “Designated Defensive Marksman”—which is to say a sniper—for its Baghdad theater of operation.22 The same week that the call for a sniper to join Leon Black’s company went out, more than 250 Iraqi protesters were killed by military-grade tear gas canisters and live fire from an array of irregular “security forces” in Iraq, including snipers. The countrywide youth-led protests, past their half-year mark, have galvanized the Iraqi public’s frustration with crushing corruption, unemployment, and heavily deteriorated living conditions—in short, the immeasurably traumatic and ongoing legacies of the Gulf Wars. Inevitably, some artists and organizations—MoMA Divest, the Veterans Art Movement, and thirty-seven artists participating in the exhibition—have called on the museum to “divest” itself of Leon Black and other unsavory funders in an open letter.

This “toxic philanthropy” narrative rushes to fill the void left by an absence of conceptual precision and clear thinking about “empathetic” exhibitions like “Theater of Operations.”23 In the case of the 2019 Whitney Biennial, Warren B. Kanders was a peripheral figure easily sacrificed to preserve the broader unity of the philanthropic apparatus. Leon Black is impunity incarnate, his wealth and power so vast that even publicized connections with the late pedophile Jeffrey Epstein, let alone war crimes in Iraq, have not moved him from MoMA’s board. This may be one reason why that open letter sent to the MoMA board, administrators, and curatorial staff was ignored, save for refusals of the artists’ requests to register their objections in the galleries by updating their work. Yes, these artists had not been previously aware of the relationship between Black and Blackwater; they learned of this long-public fact at the time of the exhibition’s opening from the authors of this essay. This is not a recrimination but a broader comment on the political limitations of haphazard or belated artistic denunciations of “toxic philanthropy.” Not only is such philanthropy immanent to the social basis of art under capitalism; curatorial malpractice here and elsewhere exacerbates and disguises the problem, trolling the political consciousness of artists by pressing catchall liberal-ethical messaging into ever greater and more explicit contradiction with the facts of the museum’s economic reality.

As far as haphazard and overwhelming thematic exhibitions go, “Theater of Operations” was in some sense par for the course: An unwieldy conceit. A doddering artist list whose magnitude and claims to exposure and discovery belied its procurement from a small number of prominent private collections. An eccentric catalog, to which one of the authors of this piece contributed an essay. For all of the show’s problems, there remain works that should be seen, conversations that ought to be had, failures that need to be documented. Unfortunately, while the exhibition’s curators rightly noted that the time for an examination of Iraq is overdue, there seems to have been little research or thought given to the specific time period addressed—a period which, properly framed, could have allowed PS1 to show how advanced creative work can turn received ideas about history on their head.

Our title, besides being a riff on the activist group-cum-slogan “Decolonize This Place,” is meant to make the negative image of cultural “decolonization” productive, especially as raised by the specific institutional and historical frame of “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011,” a recent exhibition at MoMA PS1 in New York. Activist reaction aside, we wonder how the immanent violence of the institution might be thought here in terms of the intellectual duties of exhibition. We are prompted also by a recent work by Francisco Godoy Vega, who has proposed a “recolonial” understanding of exhibitions of Latin American art staged in the Iberian peninsula during roughly the same period covered by “Theater of Operations”—a similar historical encounter between the avowedly redemptive cultural politics of “decolonization” and the political economy of colonialisms past and present. See Francisco Godoy Vega, La exposición como recolonización: Exposiciones de arte latinoamericano en el Estado español, 1989–2010 (The exhibition as recolonization: Exhibitions of Latin American art in the Spanish state, 1989–2010) (2018).

“Souvenirs of Gulf War Find Way to Museums,” New York Times, May 28, 1991 →.

Allan Sekula, “War Without Bodies,” pamphlet and article in Artforum, November 1991.

See Rijin Sahakian, “A Reply to Nato Thompson’s ‘The Insurgents, Part I,’” e-flux journal, no. 48 (October 2013) →. The historian Keith Watenpaugh has argued that the “history of modern humanitarianism tells us that at the center of humanitarian reason is a project of unstrangering the object of humanitarianism.” What he means is that humanitarianism belongs not to the liberal schema of stranger-ethics, that opening up of “compassion—as opposed to pity—to the generic stranger,” but rather positions its others as “knowable, similar, and deserving.” See Keith Watenpaugh, Bread from Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism (University of California Press, 2015), 19. For a broader view on the epistemic implication of the humanitarian frame in the construction of “global” historical narratives, see Daniel Bertrand Monk and Andrew Herscher (and respondents) in “A Discussion on the Global and the Universal,” Grey Room 61 (Fall 2015): 66–127.

In private discussions with one of the authors of this article and various exhibition participants, the curators of this show have contended that PS1 and MoMA are distinct entities. This is essentially untrue. The chairman of the board of the Museum of Modern Art has a permanent appointment, ex officio, on the PS1 board. Insofar as PS1 is, for historical and logistical reasons relating to the public land it occupies, a separate legal entity, MoMA is the “sole corporate member” of that separate legal entity. Here is how MoMA has described this relationship in its tax filings: “The Museum as sole Member of PS1 Contemporary Art Center, Inc (DBA MoMA PS1). In 2000 MoMA PS1 and the Museum entered into an affiliation to promote the study, knowledge, enjoyment and appreciation of modern and contemporary art through a collaborative program of exhibitions, research, special projects and other educational and curatorial activities. MoMA PS1 retained its separate corporate status and is a support corporation of the Museum with the Museum as its sole corporate member. The Museum has the right to appoint all members of the MoMA PS1 board of Directors. MoMA PS1 and the Museum entered into a management assistance and services agreement whereby the Museum provides management assistance and service to MoMA PS1 in certain areas, including accounting and payroll, fundraising and development, coordination of MoMA PS1’s information technology, insurance and legal affairs.” Museum of Modern Art, Internal Revenue Service Form 990, Schedule I, Part IV, Page 2 (2016).

A. B. Krongrad served as the executive director of the CIA from 2001 to 2004; see his bio here →. He briefly served on the board of Blackwater, resigning after an incredible episode in which his brother, who was then the State Department inspector general and therefore responsible for investigating the company, perjured himself when asked under oath if his brother A. B. was on its board. See Scott Shane, “Brothers, Bad Blood and the Blackwater Tangle,” New York Times, November 17, 2007 →.

Mostafa Heddaya, “An Outsourced Vision? The Trouble with Iraq’s ‘Neocolonial’ Venice Pavilion,” ARTINFO, April 2, 2015 →. In a review of Tamara Chalabi’s 2011 family memoir, a New York Times reporter fondly recounts meeting her while embedded with US Special Forces: “The Chalabis occupied the one intact structure on the bombed-out, postage-stamp-size air defense installation, while we camped in the twisted ruins and fly-infested dirt. Tamara graciously shared with me the transformer shed she had rigged into a shower.” Linda Robinson, “By the Banks of the Tigris,” New York Times, January 21, 2011 →. Bookforum’s reviewer was less sanguine: →.

See Mike Stone, “Apollo Global in Talks to Buy Constellis,” Reuters, August 5, 2016 →.

Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011, exhibition catalog, eds. Peter Eleey and Ruba Katrib (MoMA PS1, 2019), 10.

Theater of Operations, 27.

We are influenced in this formulation not only by the exhibition’s reanimation of Jean Baudrillard, to whom we will briefly return below, but also by Baudrillard’s emplotment in a broader intellectual history, one critically engaged by Lutz Niethammer’s Posthistoire: Has History Come to an End?, trans. Patrick Camiller (Verso 1994), and Hal Foster’s The Return of the Real: Art and Theory at the End of the Century (October Books, 1996), in which the term “posthistorical museum” also makes an early appearance. In an evocative footnote, Foster quotes the artist Ashley Bickerton’s posthistorical identification with an end of politics: “We are now in a post-political situation,” 257n34.

Kate Fowle, “Foreword,” in Theater of Operations, 7.

As Enwezor wrote about “The Short Century”: “Perhaps there is a need to clarify a central operating principle of this exhibition, namely to examine the link between independence movements and liberation struggles as methods for achieving African political autonomy and cultural self-awareness.” Okwui Enwezor, “An Introduction,” The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945–1994, exhibition catalog, eds. Okwui Enwezor and Chinua Achebe (Prestel, 2001), 11.

Jason Farago and Tim Arango, “These Artists Refuse to Forget the Wars in Iraq,” New York Times, November 15, 2019 →.

See MoMA’s description of the exhibition on its website →.

Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (Indiana University Press, 1995), 24. The granting of keystone catalog real estate to that catastrophizing Cassandra of posthistory is meant as a keyword association with the Gulf War but is also a calling card for the “posthistorical museum” itself, which took shape during the very same period called into question by this exhibition. For Baudrillard, the Gulf War was a case study in the violent mediations of “anorexic history” that he, along with other diagnosticians of posthistory on either side of the Atlantic, had signaled in the penultimate decade of the twentieth century. “Theater of Operations” portends to dissolve this old posthistory, what with its past flattening of Iraqi agency, only to propose a new one that sounds just like it—a “contiguous globalized ether that presupposes a borderless relationality internally consistent with itself,” per the curatorial jargonization.

See Rijin Sahakian, “It Is What It Is,” Jadaliyya, February 22, 2012 →.

“Francis Alÿs on his Embedment with the Kurdish Army in Mosul,” Artforum, February 9, 2017 →.

Dia Azzawi darkened the gallery room that held his work Mission of Destruction (2004–07) on February 6, 2020, to mark the anniversary of Colin Powell’s UN speech claiming that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. On the same day, and to mark the same event, Wafaa Bilal held a performance, October, that involved altering books that visitors had brought into the museum, which were to be sent to the College of Fine Arts in Baghdad.

In his words: “By remaking this piece yet again through its unmaking, I claim my right to resistance, in the museum, and in solidarity with Iraqis leading a revolution against their destruction and exploitation today.” See the video of Yass delivering his statement on YouTube →.

According to a spokesperson for the museum, “There are no circumstances under which MoMA PS1 would accept the destruction of artworks or aggression towards our staff or visitors. When a few dozen protesters arrived at MoMA PS1 on the last day of ‘Theater of Operations,’ they were offered public space within the museum to be heard. The protesters’ threats to staff, property, and art forced the temporary closure of several exhibition galleries to the public. We are proud of the unwavering respect and professionalism our team showed to all.” Quoted in Alex Greenberger, ARTnews, March 2, 2020 →.

The listing, which has since disappeared, was posted on the Constellis website →.

The term “toxic philanthropy” came into currency around the public strafing of Whitney trustee Warren B. Kanders in connection with that museum’s 2019 biennial, where, like “Theater of Operations,” liberal-ethical messaging (and contemporaneous media outrages) highlighted a longstanding institutional affiliation with carceral border policing, at least in the form of Kanders’s business interests. While the public humiliation of plutocrats is never unproductive, “toxic philanthropy” is nevertheless an imprecise sobriquet: it turns the identity of capital into a reformable trait. David Joselit recently proposed a parallel if ultimately different diagnosis of the “double bind” between artistic reaction and institutional messaging. See Joselit, “Toxic Philanthropy,” October, no. 170 (Fall 2019). For an example of the toxic philanthropy narrative used in the context of “Theater of Operations,” see Zachary Small, “Michael Rakowitz Wants to Pause His Video Work at MoMA PS1 as a Protest Against Museum’s ties to ‘Toxic Philanthropy,’” The Art Newspaper, December 2, 2019 →.