Julia Child and Craig Claiborne are sitting in a small wine bar at the Pittsburgh airport, luggage at their feet.

Julia: Thinking about new developments and fashions in cookery always makes me slightly anxious … We have a certain fear of ephemerality, the recognition of time as cookery’s enemy and master, and yet the Platonic ideal of the perfect form of the dish is still something of a rigid precept.

Craig: This is how information passes among generations: formulas, or recipes, allow the constant re-creation anew. The work is reborn each time in its perfection. This does seem to make cooking a type of performance, like a musical score. Perhaps Michael Fried, who has led to this reconsideration on our part, is incorrect in his judgments of theatricality, for example?

Julia: There is always that possibility, yes. But thinking of Plato reminds me that his writings on the judgment of our labors is even more dismissive. In the Gorgias, Socrates demolishes the concept of rhetoric as art by classing it with cookery. Even worse, he makes reference to the idea of the production of an “experience,” which is what we have been discussing in contemplating restaurants high and low:

Polus: What, in your opinion, is rhetoric?

Socrates: A thing which … you say that you have made an art.

Polus: What thing?

Socrates: I should say a sort of experience …

Polus: An experience in what?

Socrates: An experience in producing a sort of delight and gratification.

Polus: And if able to gratify others, must not rhetoric be a fine thing? …

Socrates: Will you, who are so desirous to gratify others, afford a slight gratification to me? … Will you ask me, what sort of an art is cookery?

Polus: What sort of an art is cookery?

Socrates: Not an art at all, Polus.

Polus: What then?

Socrates: I should say an experience … An experience in producing a sort of delight and gratification, Polus.

Polus: Then are cookery and rhetoric the same?

Socrates: No, they are only different parts of the same profession.

Polus: Of what profession? …

Gorgias: A part of what, Socrates? …

Socrates: In my opinion then, Gorgias, the whole of which rhetoric is a part is not an art at all, but the habit of a bold and ready wit, which knows how to manage mankind: this habit I sum up under the word “flattery”; and it appears to me to have many other parts, one of which is cookery, which may seem to be an art, but, as I maintain, is only an experience or routine and not an art.

Craig: Heavens! … Is cookery manipulation, let alone flattery? I could easily imagine these Greeks at dinner lavishly praising the cooks’ art.

Julia: Greeks saw meals as social rituals more than occasions for self-gratification. In the symposia—the post-banquet drinking parties—elite thinkers met and formed the polis by dint of their discussions.

Craig: [gesturing with his half-empty wine glass] We have snagged the term “symposium” for our modern panel discussions—with or mostly without wine.

Julia: The Greeks derided the Persians for excessive luxury, especially in dining, which they interpreted as weakness, possibly femininity. One observer sniffed that the Greeks’ meals consisted of a porridge for lunch and a porridge for dinner. But that doesn’t mean that their cooks failed to develop sophisticated dishes.

Under Socrates’s dismissal of the arts that please as “flattery,” would the fine arts themselves—I mean painting, and sculpture, and I wonder about architecture—no longer be considered “art” by Socrates? We must think here of both Kant and Fried.

Michael Fried

Gottlieb Doebler, Immanuel Kant, 1791.

Craig: [pauses] In the modern period, ostentatious overreaches from periods of concentrated wealth have been tirelessly stripped away.

Julia: But we must ask if our repertoire has become static—flattering diners without challenging ourselves or them.

Perhaps the work of great creators is in the past, when chefs were truly inventors, not interpreters, and the spark of genius is missing.

Craig: [takes another sip of wine and gestures with his glass, spilling a few drops] The classical repertoire can still be superb, and enjoyed in many restaurants and homes. Last spring we were invited to dine by M. Jean Cruse and his wife. Their eighteenth-century chateau “produces a variety of excellent wines, and also contains one of the finest private kitchens in the land.”1 In such great houses, at least, one can still dine well.

Detail from a fresco from Chehel Sotoun palace. Esfahan, Iran, ca. seventeenth century.

Julia: No doubt. [mischievously] Forgive the indelicacy, but wasn’t M. Cruse embroiled in “Winegate,” the unfortunate incident of inferior and adulterated wines, labeled as Bordeaux, especially for export to America?

Craig: Some unfortunate and hasty decisions were made, to meet the enormous demand for wines … [pours each of them another glass of wine]

Julia: Hmm … now, perhaps, the American monster corporations, agribusiness and the like, are the creators—but in their hands cooking is precisely a chemical art! For wholesome ingredients they substitute artificial and suspect chemical horrors, because their major criterion is not delectability but profit. Their taste runs to money rather than to satisfaction or transport of the senses.

Craig: We’ve circled back to chemistry—“food science”—leaving aside the sad case of wine adulteration and fraud you raised. But food industry executives, like M. Cruse, don’t dine on junk food, or bogus wines.

Julia: Maybe, like the great classical—and Romantic—composers, the great chefs are all dead. Today’s chefs often represent themselves as keepers of a great tradition rather than as brash innovators. Curators rather than creators.

Craig: They’ve been saying that since the Revolution.

Julia: And since then, a steady stream of French chefs have chosen to migrate—first to England at the height of empire, and now to America … The art market, I hear, has also decamped wholesale to New York from Paris; we may then expect the cutting edge of cooking to arrive there soon as well.

Julia: Could we get back to theatrics? If we think of stage artistry as being the simulation, the faking, of an emotional response, while the creation of plays or of paintings is taken as the genuine expression of emotion, then stage artistry is the lesser art, because we value authenticity above simulation. This is the Romantic idea, I believe, and we are still dominated by it to a great degree today.

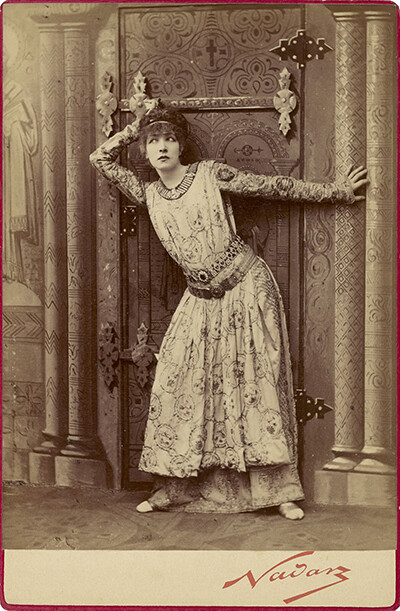

William and Daniel Downey, Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou’s “Theodora,” 1884.

Craig: Artists today seem to be trying to get away from that idea, are they not? They dislike the idea of being slaves to emotion. But that Romantic attitude is probably what prompted Stanislavski to recommend to actors that they kindle in themselves a real emotion—then “genuineness” will actually produce the emotion that is called for. [Puts his hand on his heart, theatrically.]

Authenticity is much sought after, as we live in an era very conscious of the rising tide of commercialism. But it is elusive—it is the aim of commercialism to simulate emotion that viewers will react to positively.

Julia: But I’m thinking about judging things as art.

Craig: But how? We judge food by whether it gratifies our taste and our vision.

Julia: Then why bother to think about it as theater? There is a distance between spectator and performer … Drama, comedy, music, dance, and athletics moved out of private houses into public arenas where there was such a distance. Only then, people began to see these occupations as noble, as inspiring in a great sense, a public sense—to think of them as what we today think of as art, different from just “life.”

Craig: You mean when patrons stopped subordinating artists directly to their wishes?

Julia: Something like that. When music of court and chamber served as background, an accompaniment to social interaction, then music wasn’t venerated as a high art. Music had to be divorced from that setting, to have a room of its own, to use Virginia Woolf’s metaphor, and command people’s primary attention, before it joined the high arts.

Craig: Yes, it had to become sufficiently “useless”—not instrumental [giggles] to other purposes.

Julia: But food is still very much part of the setting for social interaction. [She offers him a bowl of nuts.]

Craig: Art also serves this function. Not in museums or galleries, perhaps, but in people’s homes. Nevertheless, there are art lovers, and there are food lovers …

Julia: And theater lovers. But the lack of commonality of experience intrudes on cooking more than it does on theater. Art lovers share experience by talking about art, with a shared vocabulary. But I can never taste your morsel of food, and the number of people who can directly experience a single culinary work is quite limited …

Craig: Let’s compare connoisseurship in wine with connoisseurship in food. Then wine is a kind of multiple, a limited edition, which preserves its market value and aesthetic worth, in contrast to an art multiple, which has the potential of being infinitely reproducible.

Julia: It is just this dilemma that caught M. Cruse—how to preserve the allure of a fine but limited product while making enormous amounts of cash from volume sales. American food giants have the edge there, because for most households, quality in food is more about preserving technical safety and scientific nutrition than purity or limited production, meaning exclusivity.

Craig: For luxury goods, scarcity is precisely the selling point, even when, as with wine or perfume or cars or gowns, what we see is limited production, the product of artisans invested in the product and not the mass-produced output of an industry. Some European luxury cars are like handmade precision watches—or rare wine—

Julia: Or art.

Craig: To return to our concerns, I say classic cuisine is a victory of refinement and civilized tastes over the simple, natural, one might say brute, appetites. People of all ages, conditions, and estates must eat—but we appeal to the higher faculties of taste when we are involved with cooking as art.

Julia: Austin de Croze, the very man who successfully introduced the resolution to the Salon d’Automne in 1923 that cooking be considered one of the major arts—

Craig: The Ninth Art, if I recall, alongside Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Engraving, Music and Dancing, Literature and Poetry, the Cinema, and Fashion.

Julia: [grimacing] Yes, yes—de Croze wrote: “Cooking (of course we speak of good cooking, not that of ignoramuses and amateurs), being an art, has evolved and is evolving, slowly, without those crises caused by Fashion, but according to the traditions not only of the old cooks but of the common life of the people.”2

Craig: Civilized man ennobles his instinctive needs by transforming them into esthetic pleasures … But not everyone in a civilization is equal to everyone else. For some, eating is just satisfying a bodily appetite, and for them, presumably, so is sex. As Brillat-Savarin himself said about dining, “Animals feed themselves; men eat; but only wise men know the art of eating.”3

Julia: The bodily appetites, as you call them, certainly don’t enjoy the prestige of the intellectual or spiritual appetites—why, the OED defines the fine arts as “those in which the mind and imagination are chiefly concerned.” De Croze himself asked the question of materialism versus idealism—the traditional question of art:

Does gastronomy deserve such glory? … It is so materialistic! As a matter of fact only idealists have proved themselves capable of becoming connoisseurs of food and beverages, recipes, and good taste … There is something more than materialism in good cookery, something of ideal thought, something which is so closely concerned with the most intimate and instinctive spirit of every race, tribe, clan, family, individual that the dishes of a nation will reveal her soul more certainly than any other factor.4

Craig: Bravo! “Now, the sense of taste falls properly into the realm of aesthetics. A nation that thinks critically of its food is certain to think critically of its painting, writing, acting, music, and objets d’art. The arts have always flourished most opulently in cities where people lived well and paid a reasoned and critical attention to their senses … and the arts of dining and banqueting flourished concurrently.”5

Allan Ramsay, David Hume, 1711–1776. Historian and Philosopher, 1754.

Julia: The question of taste has always been problematic in relation to gastronomy though. Already in the eighteenth century the philosopher David Hume commented on the error of trying to locate objective standards of taste relating to quality or beauty:

Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty … To seek the real beauty … is as fruitless an inquiry, as to pretend to ascertain the real sweet or real bitter. According to the disposition of the organs, the same object may be both sweet and bitter; and the proverb has justly determined it to be fruitless to dispute concerning tastes.6

Craig: But Hume affirms that some people are better able than others to develop their tastes—which are responding to real qualities—and thus they can be guides for others:

Though it be certain, that beauty and deformity, more than sweet and bitter, are not qualities in objects, but belong entirely to the sentiment, internal or external; it must be allowed, that there are certain qualities in objects, which are fitted by nature to produce those particular feelings … Where the organs are so fine, as to allow nothing to escape them; and at the same time so exact, as to perceive every ingredient in the composition: This we call delicacy of taste.7

Julia: [draining her wine and raising the empty glass] Splendid!

Craig: [matching her gesture] “If the French consider cooking an art and insist that eating well is a mark of civilization, it is not because materialistic pleasures are given too much importance. On the contrary, it is because they seem unimportant in themselves if they are not raised to the level of an artistic achievement.”8

Julia: Ah! Again we see that leaving behind nature in favor of culture, or “civilization,” is seen as basic to the definition of an art. But it seems especially necessary for ingestion, which otherwise is inarguably about materiality, and even need.

Recipe: Greek Garum9

Ingredients:

–3 kg of small, whole uncleaned fish (anchovies, mackerel, sardines)

–500 grams (2 cups plus one tablespoon) of sea salt

–500 grams (2 cups plus one tablespoon) of coarse salt

–2 bay leaves

(The finely grained salt penetrates the fish; the coarse salt allows greater separation of the salt from the final sauce, making it less salty.)

Directions:

Rinse fish under running water; cut into smaller pieces. In airtight jar, layer the fish well with the salt. After the second layer, place the bay leaves.

Seal jar as tightly as possible and leave at room temperature.

Every three days, stir the mixture with a wooden spoon.

After 35–40 days, filter the mixture through a double-fine mesh strainer lined with cheesecloth.10

The resulting liquid is the garum. Place it in a closed glass jar. Refrigerate, and use within 2–3 months.

Craig Claiborne, Classic French Cooking (Time-Life, 1970), 20.

Austin de Croze, What to Eat & Drink in France; A Guide to the Characteristic Recipes & Wines of Each French Province, with a Glossary of Culinary Terms and a Full Index (Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd, 1931), xii.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste: or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, trans. M. F. K. Fisher (Liveright Publishing, 1948), 15.

De Croze, introduction to What to Eat & Drink in France, xi–xii.

“Publisher’s Preface” to The Physiology of Taste, by Brillat-Savarin, ix–x.

David Hume, “Of the Standard of Taste,” in English Essays from Sir Philip Sidney to Macaulay, ed. C. W. Eliott (1757; P. F. Collier & Son, 1910), 206.

Hume, “Of the Standard of Taste,” 210.

Fernande Garvin, The Art of French Cooking (Bantam Books, 1958), 6–9.

Adapted from Giorgio Pintzas Monzani.

The solids remaining in the strainer are called allec but difficult to use in modern cooking. If you wish to try, place them in a glass jar and use within two months.