It has now been almost three years since the June 2015 referendum in Greece, and these three years have demonstrated an alarming acceleration of the multiple crises that Europe faces. Nationalism and the far right have rediscovered their power in the streets and parliaments of Europe, in both North and South. Even in the contemporary art world, we see the emergence of the alt-right, which audaciously presents itself as revolutionary and progressive, shouting at the top of its lungs about its right to exist.1

At the same time, long-delayed, urgent discussions on decolonization in Europe are taking place not only within governments and the mainstream media, but also within museums and the cultural field at large. There has finally been the addition of much-needed voices and positions from outside the Western canon. Nonetheless, these voices are usually framed not only by white people but by white logics. Institutions, biennials, and mega-exhibitions attack colonial pasts, but not presents. They are quick to be politically correct and “host” the Other—while often maintaining an all-white staff, and a clearly rigidly Western approach as to how to institute.2

Before attempting to address what is to be done, one must first understand the limitations of the contemporary art institution and the mega-exhibition. These forms fail to escape the mechanisms of power they wish to condemn, since they cling to a notion of “civilization” with roots in modernism that continues to structure particular modes of discourse.

Imperialism, nationalism, and capitalism form the corners of a triangle built and sustained to this day by what I call the WWW (White Western Westphalian) order of patriarchy. The three components of the triangle—are in fact communicating vessels that are deeply interconnected—and they define, ignite, sustain, and perpetuate crises. As with most institutions of the capitalist state, the contemporary art institution cannot escape these three components.

In the center of the triangle lie crises, whether ethical, financial, or democratic. I will look into contemporary art discourse in relation to the three components of the triangle, attempting a reading from the geographical perspective of Greece, in order to explain why this particular country offers a pathway to dismantle the “universal truth” of civilization that the WWW patriarchal order seeks to impose. Greece is unique in that it has been appropriated throughout modernity as the mother of the Western canon—as the country on whose “fantasy” the contemporary WWW order was built.3

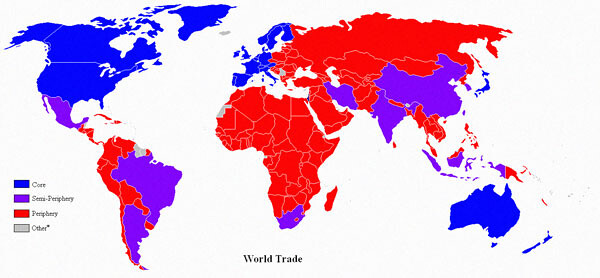

A world map with countries differentiated by color, according to their role in global trade. Countries that constitute the “core” are blue; countries in the “semi-periphery” are purple; and countries in the “periphery” are red. Based on Christopher Chase-Dunn, Yukio Kawano, and Benjamin Brewer, “Trade Globalization since 1795,” American Sociological Review 65, no. 1 (February 2000).

Imperialism, Nationalism, and Greece: Guest Nation from Past to Present

The country is currently impoverished; citizens and residents feel alienated and betrayed by their state and are unwilling to deal with their uncertain present—let alone look toward the future. Capitalism and its discontents have led to the fierce rise of nationalism within the country. The neo-Nazi political party Golden Dawn is growing, operating for some as an outlet for anger and frustration.4 A recent documentary by filmmaker Håvard Bustnes, titled Golden Dawn Girls, follows the life of three women: a wife, a mother, and a daughter of three different Golden Dawn members of parliament. “What has happened to Greece?” wonders Bustnes out loud at the start of this disturbing documentary. When I asked Bustnes what shocked him the most while filming these women, he replied: “That they believe in the same old conspiracy theories as the Nazis during the Second World War.”5 Bustnes demonstrates how the triptych “family, religion, country”—(πατρίς, θρησκεία, οἰκογένεια) a favorite slogan of Greece’s military junta in the 1970s—has shaped the rhetoric of Golden Dawn and lured in desperate Greeks.6 This triptych taps into the national identity of “Greekness” as defined and embedded within Orthodox Christianity and the fantasy of an ancient lineage leading back to the golden age of Pericles. It symbolizes strength for citizens who feel lost, forgotten, or toyed with by the EU—and even more so by their own corrupt politicians.

This phenomenon is visible across the peripheries of Europe. In recent trips to Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, Kosovo, and the Czech Republic, through discussions with locals and colleagues, I traced common factors forming the sentiment that has greatly influenced recent elections and the rise of the far right: unhappiness with the capabilities and functions of the governments of these countries, leading to a desire on the part of many citizens to align with the European ideal of the strong sovereign state. This ideal state is functional and transparent, provides welfare benefits to its citizens, but fights off EU “meddling” with its supposed sovereignty. The desire for this state results is a simultaneous attachment to a (fictional) national identity, and a resentment towards the Other. This Other is both the “better-off” Other (rich Northern Europeans) and the disenfranchised Other (refugees and migrants). The latter of course is the easiest to attack and blame for all the ills of the world.

When examining the European identity myth, which by default encompasses Christian whiteness and the supposed universal of civilization, we need to remember Boaventura de Sousa Santos’s description of “internal colonialisms” in Europe, as well as his distinction between different kinds of colonizers. Santos categorizes colonizers into two groups: core countries of the continent with a colonial past that produced their wealth, but which also sustains this wealth today through internal colonization of weaker EU members; and semi-peripheral countries like his native Portugal, which used to be colonizers but are now financially weak and internally colonized.7 I add here a third category to his useful schema: the peripheral countries of Greece and most of the Balkans that have no colonial history and sit largely outside the Catholic/Protestant club. Their financial weakness and constant lack of sovereignty (among other factors) blocks them from becoming core countries.8

Gottlieb Bodmer, Portrait of King Otto of Greece, c. 1835. Copyright: Wikimedia Commons.

The creation of the modern Greek state in 1832 involved the de facto lack of sovereignty of the country, when the Great Powers appointed the seventeen-year-old Bavarian Otto as the king of the newly founded state. This lack of independence in state affairs would continue throughout the following centuries: via the genocide of Greek minorities in Asia Minor in 1922, or during the resistance against Nazi occupation from 1940–44, when the British funded Greek leftist guerrillas to fight Hitler.9 Churchill then “gave” Greece to the US so as to halt the spread of communism to the Mediterranean, thus causing an extremely bloody civil war (1944–49), considered to be the first proxy conflict of the Cold War. Remnants of this conflict still politically divide the country today. Social turmoil following the assassination of progressive politicians by paramilitary forces led to the US installing a dictatorship in Greece in 1967, which deepened the divide and created the core leaders of today’s Golden Dawn. After the reinstatement of democracy in 1974, the deals made by Greek politicians to secure a place in the EEC (now the EU) involved shady arrangements, extraditions, and “exchange deals,” demonstrating not only a lack of Greek sovereignty but its true role as a proxy state. Greece’s desire to finally be accepted by the white Western club is encapsulated by Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis’s infamous 1976 speech: “Greece politically, defensively, economically, culturally, belongs to the West … Be it traditionally or because of interest, of course we belong to the Western world.”10

When it comes to the East/West divide, Greece has historically only been concerned with the extent to which it does or does not belong to the West—meaning there is a denial of any connections to the East, be that the Middle East, Turkey, or Asia Minor. This is the reason for the phrase “our own East” (ἡ καθ’ ἡμᾶς Ἀνατολή), which marks a geographical and cultural break with the East.11 In 1996, Samuel Huntington’s book The Clash of Civilizations claimed that Greece has never belonged to the West because it is predominantly Orthodox Christian.12 The majority of Greek intellectuals and politicians rushed to dismiss Huntington’s idea with a nearly existential anxiety, insisting that Greeks do not belong to the category of otherness.

Today, after a failed referendum and many memorandums, after being ridiculed for not yet becoming civilized enough, European enough, orderly enough, financially balanced enough, or in fact white enough, contemporary Greece is counterposed to the image of its “ancient glory.”13 This ancient glory has proven dangerous not only in the hands of neo-Nazis, but also in the hands of the leftist intelligentsia of the EU, which has reprimanded Brussels not for imposing policies that violate human and citizen rights, but for mistreating the “mother of the European idea.”14 But Greece’s self-image has gone through the blender of the West and mutated into something alien, to then be redistributed as the ultimate root and example of civilization’s “universal truth.”

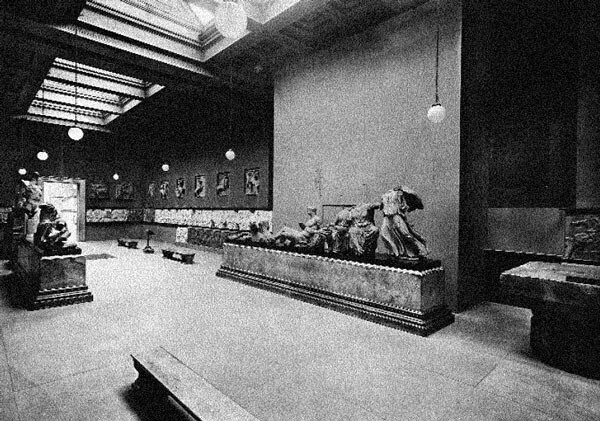

The Elgin Room at the British Museum, 1937. Copyright: Wikimedia Commons.

Host Versus Guest, via the European State

With Greece’s unsovereign pasts and capitalist histories in mind, its newfound nationalisms are to be expected. This January, Greece’s Syriza government brought the naming dispute over Macedonia again to the fore of public discussion. The dispute led to marches that same month in the city of Thessaloniki (capital of the prefecture of Greek Macedonia) and later in the capital Athens, against FYROM—the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, commonly referred to as Macedonia. It is not by chance that this issue has resurfaced today, after initially flaring up in the mid-1990s, when diplomatic incidents with both FYROM and Turkey strengthened the presence of Golden Dawn, a then-marginal paramilitary group that slowly gained enough traction to become, in 2015, a political party with representatives in the Greek parliament.

Somehow, the links between Europe’s core financial countries, their meddling in peripheral countries, and their influence on what I call the “Extra States” (the IMF, Troika, etc.) has remained opaquely addressed or completely bypassed in recent discourses during and after mega-exhibitions that landed in the city of Athens and elsewhere.15 The last two editions of Documenta are prime examples; in addition to the central exhibition in Kassel, the 2012 edition also held a show in Kabul, and the 2017 edition in Athens. Documenta 14’s approach to Greece’s relation to modernity and nationalism was myopic at best.16 Like imperial powers, mega-exhibitions tend to arrive as they please, in different permutations in different locations around the globe, translating local realities for the sake of their (curatorial) narratives. Crises are sexy, after all. In juxtaposition to these intentions, which are naive and irresponsible at best and dangerous at worst, lies the disenchantment and hostility of locals toward the arrival of these “foreign bodies.” These feelings are not unlike the aforementioned sentiments of contemporary EU nationalist supporters. This charged interaction results from a collision of different interpretations of civilization, rooted in modernity.17

To examine these power structures that manifest through the binary of guest and host, it is useful to turn to Jacques Derrida’s neologism “hostipitality,” which might most strongly resonate when considering hospitality and its performance within the societal structures that define citizenship today in Europe, as contoured by the state.18 Within the microcosm of the art world, the same logic exists. With the term he coined, Derrida proposed that hospitality contradicts its own definition by necessarily entailing hostility:

We could end our reflections here in the formalization of a law of hospitality which violently imposes a contradiction on the very concept of hospitality in fixing a limit to it, in de-termining it: “hospitality is certainly, necessarily, a right, a duty, an obligation, the greeting of the foreign other [l’autre étranger] as a friend but on the condition that the host … remains the patron, the master of the household … maintains his own authority … and thereby affirms the laws of hospitality.”19

In European culture, the politics of hospitality are usually settled through state discourses on multiculturalism, where tolerance and inclusivity (or the rather abhorrent “integration policies” of the 1990s) are demonstrated via fixed notions of “diversity.”20

Yet this discourse of multiculturalism remains inhospitable toward behaviors that operate outside European “superior knowledge.” In the cultural field, and specifically in cultural institutions, the mechanism is clear: European and Western cultural hegemony imposes upon institutions a certain “civilized” way to behave. The presentation and discussion of this behavior is undeniably reminiscent of older Western notions of how a civilized host should perform toward an exotic, uncivilized other. The overintellectualization of cultural discourse, tied into Eurocentric academia, leaves all those who are not trained to write and think with excellent English skills or advanced knowledge of critical discourse—often the case in Greece, where the production of contemporary art discourse and critique is minimal—feeling irrelevant.21

Alexandra Pirici, Parthenon Marbles, 2017. Work performed on the Acropolis Hill in Athens. Commissioned by KADIST and State of Concept Athens, under the auspices of Future Climates. Photo: Alexandra Masmanidi.

Host Versus Guest in Contemporary Art

Unsurprisingly, the Western “universal” canon of contemporary art always remains the host—setting the rules and terms of discourse—even when it is a guest. Discussions on decolonization, de-modernization, and the art world’s current obsession (bordering on fetishistic) with “the Other” via indigenous artists were prevalent at a recent conference called “Collection in Transition: Decolonising, Demodernising and Decentralising” at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.22 At the conference I was reminded of how Greece embodies the root of all modernity’s evils. In one conference presentation entitled “Demodern: Why?” Geeta Kapur looked at modernity from the topos of India: “When I say ‘Demodern: Why?’ one needs to understand that this question comes from a particular situation, from a particular location … I speak from India and this is important.” She then clarified that her position is not a nationalistic one, but rather “a plea to reconsider situation and location as important historical positions that problematize the legacy of modernity,” stating the obvious: there was never one modernity as such. Reflecting on my own locality, I would like to note that although Greece’s appropriation throughout modernity as the mother of the Western canon is documented, not much has been said about how its ancient histories have been so consistently mutated and translated according to the desires of that order. Could this focus on the appropriated, mutated, and mistranslated notions of a place and its histories, particularly in the case of Greek antiquity and its culture, provide a way to deconstruct the very root of the signifiers of the Western canon, and unravel the narrative of the WWW order of patriarchy? Could it be retold as a story of mimesis?

During the late period of Greece’s colonization by the Ottoman Empire in the 1800s, the WWW patriarchal order started literally extracting the “glorious evidence” of the past with which it identified: ancient sculptures, temples, and artifacts. To protect the objects and keep them safely away from the ignorant and careless hands of the Greeks, the British and French transferred them to the truly civilized topos of their Empire (the British Museum, the Louvre, etc.). Possibly the most famous example is the case of the Parthenon Marbles, known as the Elgin Marbles after Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin. While traveling in Ottoman-occupied Greece, Elgin removed parts of the Parthenon frieze, using chain saws, and sent them to Great Britain. This activity was framed as preservation: redistributing cultural capital throughout Europe as a means of preserving the roots of civilization. Such capital was then further appropriated, not only via the proliferation of cultural artifacts in museums but also via the development of architecture that simulated the same ancient temples from which the columns and statues were plundered. Proof of this process can still be widely seen on buildings and museums in London, Berlin, Vienna, and Paris—providing a visual connection between the extraction and mutation of the political ideals of Ancient Greece by the Western cultural canon.23

Museums in rich European capitals, symbols of the history of Western culture as host, were and still are responsible for establishing and reaffirming the status of Western culture as a universal truth, igniting the universal canon of modern and contemporary art. The painful—and truly absurd—scandal of the damage of the Parthenon Marbles by the British Museum in the 1930s stands as the cause célèbre of this attitude. The marbles retained the residue of their original bright colors. British Museum conservators—somehow unaware that Ancient Greeks painted their statues—cleaned the marbles with strong chemicals to make them as white as possible, damaging the artifacts beyond repair.24 This whitening and whitewashing—in both a literal and metaphorical sense—can be seen as a great performative act of imposing, reconfiguring, and universalizing Western ideology through art.25

“Redistribution,” a term taken from economics, serves to explain how this ideology performs its power. Economist Dennis C. Mueller describes redistribution as one of the “major activities of the state that seems to benefit one group at the expense of another.”26 One of the main categories of redistribution in economics is what is widely described as “redistribution as taking.” Typically this process entails the removal by an agent (in most cases the state, and usually by force or with the threat of force) of goods or money owned by one person or group, followed by the granting of these goods or money to another person or group. This can be done, for example, in the form of taxation or recalculation of pensions. We have seen current manifestations of this in recent governmental policies in Greece, where, as I write, another cut in pensions has been decided, the fourth in the last five years, leaving 40.62 percent of pensions in the country at a monthly gross amount of 500 euros.27

Redistribution as taking also occurs in the context of culture via the symbolic and commodity value that cultural production generates (cultural goods, intellectual property). For the purposes of the argument here, I would like to invite the reader to look at “redistribution as taking” as the performative act of a WWW patriarchal order that expropriates and appropriates goods and property, under the name of preserving and consequently redistributing universal truth. Many have offered ways to dismantle this thinking. Achille Mbembe recently highlighted how, in situations of colonization, slavery, and apartheid, “juridical and economic procedures … lead to material expropriation and dispossession, and … to a singular experience of subjection characterized by the falsification of oneself by the other. What flows from this is a state of maximal exteriority and ontological impoverishment.”28 Greece, together with many other countries of the European periphery, has provided a grounds for expropriation in a different but similar way to the contexts Mbembe describes. Its cultural histories have been employed in order to map out the origins of Western civilization, and its artifacts used to embody the West’s aesthetics and legacies, while its people have been excluded from the superior all-white club. This is a paradigmatic form of cultural appropriation through means of redistribution as taking.29

This form of appropriation was clearly exposed in spring 2017, when Romanian artist Alexandra Pirici presented a piece titled Parthenon Marbles in both Paris and Athens. The piece was what the artist calls a “living human sculpture,” a choreographed tableau vivant with five performers imitating the poses of figures from the Parthenon frieze. The work references the Acropolis Museum’s ongoing request for the British Museum to repatriate the looted marbles back to Athens. This repatriation has been an active request of the Greek people since the reinstitution of democracy in the country in 1974. Pirici’s work also involves a textual component, produced in collaboration with curator and writer Victoria Ivanova, which is read out loud by the performers. The text narrates the story of the Parthenon Marbles and uses the notion of the derivative as a tool for identifying concrete socioeconomic advantages when it comes to holding prized artifacts (here in the case of the British Museum) and suggests a means for redistributing the value generated by the artifacts through recirculation. In Athens, Pirici chose the Acropolis rock as the site for the work, effectively proposing a performative repatriation.30

Pirici’s work is a contemporary testimony to a familiar process that has been occurring globally for more than two hundred years. The infamous case of the Parthenon Marbles in fact represents hundreds of cases of looted artifacts, operating as a metaphor and an entry point into a larger discussion about capital, accumulation, circulation, redistribution, and the role of the arts within today’s economies.

Artist Kader Attia has long addressed the notion of reparation, particularly through the activities of the space La Colonie, which he founded in 2016 in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. The space is a home to cross-disciplinary, anti-academic, artistic thought and discussions, with a variety of events that focus on art, music, critical thinking, and cultural activism. According to Attia, its main agenda is to focus on the stories of minorities in an open-ended, inclusive way. Attia’s sociocultural research led him to propose the notion of “repair,” which he believes is a constant in any system, social institution, or cultural tradition. The infinite process of repair is closely linked to loss and wounds, to recuperation and reappropriation.

Attia’s recent two-part film The Body’s Legacies (Part 1: The Objects; Part 2: The Postcolonial Body) is an extensive account of testimonies by academics, scholars, collectors, and museum directors from Canada, the US, Ivory Coast, and many other locations, relating the histories behind bodies and artifacts from the world over. Attia is currently planning on conducting more interviews in Athens, looking at the case of Greece as another ground of expropriation and cultural appropriation.

Through these two paradigms of practice, both artists underpin not only the magnitude of injustice linked to cultural heritage (and the socioeconomic and political benefits it carries) but the need for contemporary institutions to look at the legacies the modern museum has bequeathed—not simply by facilitating and presenting questions and discussions on looted and dubiously acquired artifacts, but by actively engaging in the efforts for their return.

Kader Attia, The Body’s Legacy, P. 1: The Objects, 2018. Single channel video projection, 58’21” minutes, exhibition view The Field of Emotion, The Power Plant, Toronto, 2018, Photo: Tony Hafkenscheid, Courtesy of the artist

Geographies of the Other, or How to Dismantle the WWW Order of Patriarchy

Notions of whiteness are part of the sinister triangle of imperialism-nationalism-capitalism and are nearly inextricable from the notion of the West. Admittedly, the way the West is defined has changed a lot over the years. Scholars such as Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen identify at least seven different versions of the “West,” and many could argue for more.31

When departing on a quest to define the Western and the white, one needs to take into account that the notion of “white” carries socioeconomic and political weight. The propaganda of the WWW order has always counted on including as many countries as possible in the definition of this Western whiteness, “modernizing” and “civilizing” them throughout the centuries, via globalization and capitalism, but simultaneously exploiting them.

Nonetheless, a clear trajectory belongs to particular countries that have always been part of the West, and another trajectory belongs to others that have hopped in and out of the Western wagon. They are not equally “white.” From testing the intelligence of immigrants—which was proposed by French psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon and employed on all Ellis Island immigrants (no matter how pale their skin) for a period of time—to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s distinction between the Irish and the “Caucasian Race,” the constructing of white Western identity has always been a twisted myth costing millions of lives.32 One thing is clear: whatever defines White Western Westphalia today, its de facto imposition of a supposed superiority is certainly to blame for the current socioeconomic and political realities of Europe and the world. So how could one dismantle the narrative of the WWW patriarchal order through the spectrum of culture?

Greece is only one example, but it is unique in having a particularly perverse idiosyncrasy: that of having given birth to the WWW patriarchal order’s fantasy of superiority. Paradoxically, it remains the unwanted child of an unwanted union: West and East. In light of all the discussions of the colonial past of some countries in Europe, we need to face the reality of the geo-historical positioning of modernity and its evolution up to today.

Cultural producers need to carefully reconsider the following: How can we decolonize and demodernize the very institutions we work in and with, if we continue to operate under this WWW patriarchal order that has set the rules of the institution itself? How can we decolonize and demodernize unless we look into not only the content institutions produce, but also how this content is produced: Under what rules? How is it translated into discourse? How is it displayed? In other words, “educating” and “learning” about the Other has sometimes proven uncomfortably didactic in recent contemporary art exhibitions. Since their very foundations, most Western institutions have stood as concrete reaffirmations of the universal that the WWW patriarchal order imposes. We need to admit that this order’s gaze still dictates the very way we operate within and outside of cultural institutions, excluding all other modernities. Instead of tokenizing and whitewashing the histories of cultural artifacts, artworks, and cultural producers by inserting them into the “civilized” and “enlightened” environment of the Western artistic canon, instead of “giving voice” by presenting and narrating in the name of the Other, it’s time to consider the unspoken hypocrisy of those who charitably include all yet remain within this existing narrative, forcing the Other into a Eurocentric academic description of its otherness, into a Western display method, contemporary language, or “artspeak.” If we depart from this premise, then the Western mandate for the universal—which has corroded our varied and complex cultural histories just as the chemicals corroded the surface of the Parthenon Marbles—might finally collapse.

See, for example, the situation around the LD50 gallery in London, as recounted by J. J. Charlesworth in his article “The strange case of the ‘alt-right’ art gallery,” Art Review, March 3, 2017 →.

Here I use the verb “institute” in reference to Maria Hlavajova’s call for “instituting otherwise.” lease refer to her talk at CCA Singapore “The Making of an Institution — Reason to Exist: The Director’s Review. Instituting Otherwise” March 22nd, 2017. Video soon to be available on the CCA website.

Of course, the Roman Empire is another signifier used by the WWW order—Ancient Greece being its predecessor.

A poll from January 13, 2018 shows that support for Golden Dawn has fallen 0.2 percent, but it is still the fourth-largest party in parliament, with 6.7 percent of the vote.

Private conversation with Håvard Bustnes, March 2018.

The phrase “country, religion, family” first appeared in 1851 in the writings of the Greek theologian Apostolos Makrakis. He claimed that in a vision, Christ and the Virgin Mary appeared before him to ask for the salvation of men—especially Orthodox Greeks, so they could strengthen their glorious nation. To do this, said Makrakis, the “Western ideologies” should be rejected and an Orthodox Christian state should be established. From 1880 onwards, “country, religion, family” was a common phrase in pious Christian circles in Greece, and by 1936, during the first dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas, the phrase was widely known. The colonels of the 1967 dictatorship used the phrase as an official campaign motto, making it even more popular. Golden Dawn has continued this trajectory.

Santos states in his lecture “Epistemologies of the South and the Future”: “By the eighteenth century, Portugal was an informal colony of England: it was an imperial centre that, in financial terms, was dominated by, or subordinated to, the hegemonic control of the British Empire. In addition, we also witnessed a rise of differences within the ‘Western World.’ Southern Europe became a periphery, subordinated in economic, political, and cultural terms to northern Europe and the core that produced the Enlightenment. This has been my debate with some postcolonial thinkers, particularly in Latin America, but also in Europe, who think that there is just one Europe or just one Western modernity. I think that the situation shows that from the very beginning there has been an internal colonialism in Europe. This has now become very visible with the financial crisis. In one of my studies, I argue that the Portuguese and the Spanish in the seventeenth century were described by the northern Europeans in the same terms that the Portuguese and the Spaniards attributed to the indigenous and native peoples in the New World and Africa. They were described as lazy, lascivious, ignorant, superstitious, and unclean. Such descriptions were applied to them by the monks that came from Germany or France to visit the monasteries and the people in the South.” See →.

Here, “core,” “semi-peripheral,” and “peripheral” are terms borrowed from world-systems theory and economics.

It’s worth recalling Winston Churchill’s famous phrase: “It is not Greeks that fight like heroes, but heroes that fight like Greeks.” This was propaganda proper, but Churchill shortly changed his tune, collaborated with the conservative right that had formerly worked with the Nazis, and these leftist “heroes” were exiled to concentration camps on Greek islands, where they were tortured for years, or deported to Russia after being denied their passports and nationality. For the past few years I have been conducting interviews with the remaining survivors of this conflict, collecting oral histories and testimonies. See this interesting article on the British involvement in Greece in The Guardian →.

Konstantinos Karamanlis, June 12, 1976, speaking at the Greek parliament on Greece’s entry into the EEC. Video of the speech (in Greek) can be found at →.

This phrase first appeared in 1842, with the formation of the “Great Idea” in a text by Markos Renieris, later the head of the first Greek National Bank.

Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (Simon & Schuster, 1996).

For more information on US categorizations of Greeks and other migrant communities in relation to their skin color, see Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010).

See, for instance, an interview with Günter Grass from 2012 entitled “Shame Europe!” (in German) →.

Europe’s core financial countries heavily influence the decisions of the IMF and the Troika, and in turn the IMF holds power over them and the EU parliament. The private banking sector also holds a great deal of influence in relation to all these Extra States and their decision-making. The idea of “Extra States” is developed in my upcoming curatorial project Extra States: Nations in Liquidation for Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp.

Please see my previous text co-authored with Yanis Varoufakis →

See María Iñigo Clavo, “Modernity vs. Epistimodiversity,” e-flux journal 73 (May 2016) →.

Derrida’s neologism is derived from the merging of “hostility” and “hospitality.” For more, see Jacques Derrida, “Foreigner Question: Coming from Abroad/From the Foreigner,” in Of Hospitality, eds. Mieke Bal and Hent de Vries (Stanford University Press, 2000).

Jacques Derrida, “HOSTIPITALITY,” Angelaki Journal of Theoretical Humanities 5, no. 3 (December 2000): 3–18.

For more on European integration policies towards migrants from 1973 onwards, see J. Doomernik and M. Bruquetas-Callejo, “National Immigration and Integration Policies in Europe Since 1973,” in Integration Processes and Policies in Europe, eds. B. Garcés-Mascareñas and R. Penninx (Springer, 2016).

Apart from the rare appearance of engaging critical discourse in the Greek press and public sphere, critique in Greece is usually conducted by male academics. They hail from various disciplines (often referring to themselves as “curators”), and they have a tendency to overestimate and abuse their power. They provide dated, dusty academic analyses of art, in which they exclusively quote long-dead white Northern European males, reinforcing the WWW patriarchal order.

The conference, which was organized by L’Internationale, took place on September 22, 2017.

In a cruel historical irony, these buildings designed to represent ancient glory were constructed by the same hands that had been emptied of their cultural property by the West. From the seventeenth to the early twentieth century, cheap imported labor arrived in Northern Europe from the colonies to sustain the wealth of empires. From the 1950s onwards the labor came from Greece, Turkey, Italy, North and sub-Saharan Africa, the Eastern Bloc, and the Middle East. If one reframes instances of economic “redistribution” as purposeful taking, such expropriation is clearly in line with longstanding European policies.

For extensive analysis on the 1930s cleaning of the Parthenon Marbles, see →.

Among other things, the term “whitewashing” refers to the practice in Hollywood of casting white actors to play the roles of POC. (Please see definitions on Wikipedia → and the Merriam-Webster online dictionary →.) I use the term here to indicate the traditional meaning of the term in international English (to cover up and minimize an action) but also to address the action of whitening—both literally in the case of the Parthenon Marbles, but also figurative in the “whitening” of Ancient Greece by the white European order.

Dennis C. Mueller, Reason, Religion, and Democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Paper published by the Ministry of Labour of Greece, December 2017.

Achille Mbembe, “Difference and Self-Determination,” e-flux journal 80 (March 2017) →.

This is what Clelia O. Rodriguez calls an “appropriation for intellectual masturbation.” See →.

The action took place on April 5, 2017 in front of the Parthenon on the Acropolis Hill in Athens.

Martin W. Lewis and Kären Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (University of California Press, 1997).

Painter, History of White People.

Subject

Thanks go to: Gabriëlle Schleijpen for the invitation to curate “On Guesting,” an installment of the recurring public symposium Roaming Assembly, at the Dutch Art Institute in September 2017, which provided ground for the initial notes of this essay. To colleagues and friends that offered their thoughts and support: Kader Attia, Dora Budor, Håvard Bustnes, Angela Dimitrakaki, Galit Eilat, Charles Esche, Maria Hlavajova, Victoria Ivanova, Hito Steyerl, Kate Sutton, Yanis Varoufakis, Hypatia Vourloumis, W.A.G.E., and the curatorial collective WHW. Most importantly, to my partner, Jonas, for challenging my writing in the most insightful manner.