The collapse of reality is not an unintended consequence of advancements in, for instance, artificial intelligence: it was the long-term objective of many technologists, who sought to create machines capable of transforming human consciousness (like drugs do). Communication has become a site for the extraction of surplus value, and images operate as both commodities and dispositives for this extraction. Moreover, data mediates our cognition, that is to say, the way in which we exist and perceive the world and others. The image—and the unlimited communication promised by constant imagery—have ceased to have emancipatory potential. Images place a veil over a world in which the isolated living dead, thirsty for stimulation and dopamine, give and collect likes on social media. Platform users exist according to the Silicon Valley utopian ideal of life’s complete virtualization.

A conversation about immortality acquires a lot more meaning when we are in the middle of a pandemic and so many people are sick and dying. I think this present moment is a bit similar to the original context that triggered cosmism: all the epidemics, droughts, and famines in nineteenth-century Russia. But now there is also the fear of planetary ecological collapse and extinction, and in this context the idea of resurrection becomes much more urgent. There is also a certain hopelessness produced by the decline of reason and social progress, both of which have been encountering countless setbacks in recent decades. All of this makes the delirious optimism of cosmism meaningful and moving, in my opinion.

Along with being an index of democracy, art is also a lucrative niche for the global entertainment business. Art has thus become a form of consumable merchandise, destined to be used up. In this situation (diagnosed by Arendt and others in the 1960s), artists have either embraced this quality of art as merchandise (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst), or rejected it in the name of politicization and criticality (Hans Haacke, Andrea Fraser, Hito Steyerl). With globalization, critical artists have been summoned to become useful by surrendering art’s (always partial) autonomy and taking up the task of restoring what has been broken by the system. So they denounce globalization’s collateral damage and contemporary art’s woeful conditions of production. They imagine a more just future, produce political imaginaries, disseminate counter-information, restore social links, gather and archive documents and traces for the “duty of memory,” etc. Perhaps, then, the prior role of the artist as a cultural vanguard has given way to a mandate to cultivate a feeling of political responsibility in spectators, in the name of self-representation and the representation of Enlightenment values.

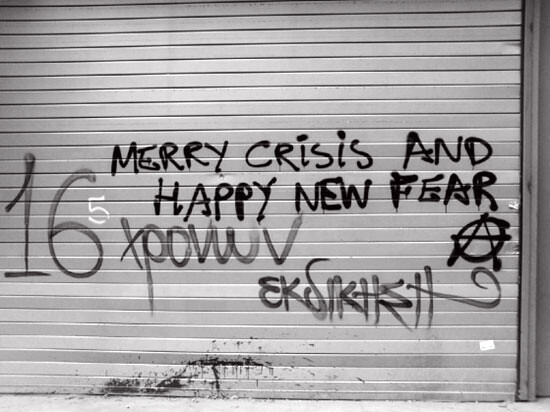

In our neoliberal era, subjectivities are being further shattered by absolute capitalism and its crisis of human, environmental, and interpersonal relations manifested, for instance, in femicide; or in the transformation of the mechanisms of love (feelings, emotions, seduction, desire) into commodities. Brokenness also stems from capitalist “productivity,” which means dispossessing peoples not only of their territories, but also their labor, bodies, language, lives. These forms of violence have been justified by the production of an abundance of goods, so that a portion of the global population can have anything we want, so we can live “good” lives designed by technocracy, adorned by culture, so we no longer have to make a living with the sweat of our brows. As the communist idea of cooperation is obsolete, excess production and labor achieved through violence and dispossession provide the general feeling that we can have comfort while being relieved of the pressure of contributing to society and of the feeling that we are needed by others.

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?

My taxonomy of images of alterity from the twentieth century—ethnographic, militant, and witness—is not opposed but rather transversal to Rancière’s. What I am interested in, firstly, is tracking the kinds of discourses underlying images of Western alterity in the aftermath of the postcolonial critique of the ethnographic image, the demise of the third-worldist militant image, and the exposure of the limitations of the witness image, which often serves to perpetuate the figure of the “victim.” These visibilities have perhaps become the “visual” in Daney’s sense. Second, I wish to consider the possibility of an image of soulèvement—in the sense of an image of an other that could threaten Western imperialism and capitalist absolutism, a system this is consensually driven by the desire and need for visibility, and that legitimates social Darwinism with racism and misogynist speech in the public sphere.

The double bind of modernity officially conceals the colonial carnage necessary for modern progress even as it strategically reveals this same carnage for the purpose of accruing cultural capital. The modern worlding of the world —which includes the production of objective reality by experimental science, knowledge, and design—coincides with the ruthless elimination and instrumentalizaton of certain creatures by others. This blind spot is the “habit” of coloniality, ingrained in the Western unconscious, predicating universality, progress, betterment, and growth on the eradication of alterity. This is the condition of modernity itself, even as it furnishes the resources for a critique of such systemic destruction.

The takeover, executed in collaboration with the tourism complex’s employees—waiters, security guards, maids, and gardeners, who politely escorted shaken tourists to the bus station and airport—takes place after years of planning by a team of international environmentalists, leftist guerrilla strategists, Palestinian architectural decolonists, radical cultural producers, biologists, environmentalists, an international team of anthropologists from indigenous communities, and community leaders representing one hundred of the nearly four hundred ethnicities still surviving across Mexico. The interdisciplinary team has taken up the task of organizing communal forms of living in the complex, following the desires, needs, and concerns of the natives of the mountains in Guerrero. Their goal is to reconvert the Acapulco Diamante tourism complex into a sustainable habitat by restoring the ecology of the area; one of the first tasks is to turn the pools at the luxury hotels into fish farms. Technology and know-how have been imported from Gaza to build a desalinization and water-treatment plant, and from Belgium to build a solar energy system.

WEB.jpg,1600)