Categories

Subjects

Artists, Authors, and Curators

Institutions

Locations

Types

Years

Sort by:

Filter

Done

514 documents

e-flux Events

Posted: June 6, 2024

Category

Film, Labor & Work, Feminism, Globalization

Subjects

Video Art, China, Biopolitics, Environment

“Foreigners Everywhere”

Jace Clayton

e-flux Criticism

Posted: May 30, 2024

Category

Colonialism & Imperialism, Globalization

Subjects

Biennials, Decolonization, Postcolonialism, Indigenous Art

Museum of Contemporary Art

Trade Windings: De-Lineating the American Tropics

e-flux Announcement

Posted: April 22, 2024

Category

Economy, Colonialism & Imperialism, Globalization

Subjects

Slavery

Institution

Hong Foundation

Musquiqui Chihying: Ghost in the Sea

e-flux Announcement

Posted: April 13, 2024

Category

Globalization, Labor & Work, Technology

Subjects

Africa, East Asia

Institution

African Film Institute Film Series: Sosena Solomon, Mpho Matsipa

Sosena Solomon, Mpho Matsipa, Natacha Nsabimana, and African Film Institute

e-flux Events

Posted: March 19, 2024

Category

Film, Globalization, Urbanism, Architecture

Subjects

Documentary, Africa

e-flux Criticism

Posted: March 13, 2024

Category

Painting, Globalization

Subjects

Africa, Abstraction, Decolonization

Shanghai Biennale

Raqs Media Collective: The Bicyclist Who Fell into a Time Cone

e-flux Announcement

Posted: March 2, 2024

Category

Film, Globalization

Subjects

Video Art, Time, Memory

Institution

Jane Jin Kaisen’s “Halmang”

Dylan Huw

e-flux Criticism

Posted: February 22, 2024

Category

Indigenous Issues & Indigeneity, Globalization, Labor & Work

Subjects

East Asia

The National Art Center, Tokyo (NACT)

Universal / Remote

e-flux Announcement

Posted: January 16, 2024

Category

Globalization

Subjects

East Asia, Covid-19

Institution

Multiplying Effects: Capital, Water, and Architectures of Tourism

Chang Jiat Hwee, Petros Phokaides, and Panayiota Pyla

Architecture Essay

Posted: November 20, 2023

Category

Economy, Architecture, Globalization, Nature & Ecology

Subjects

Tourism, Southeast Asia, Money & Finance

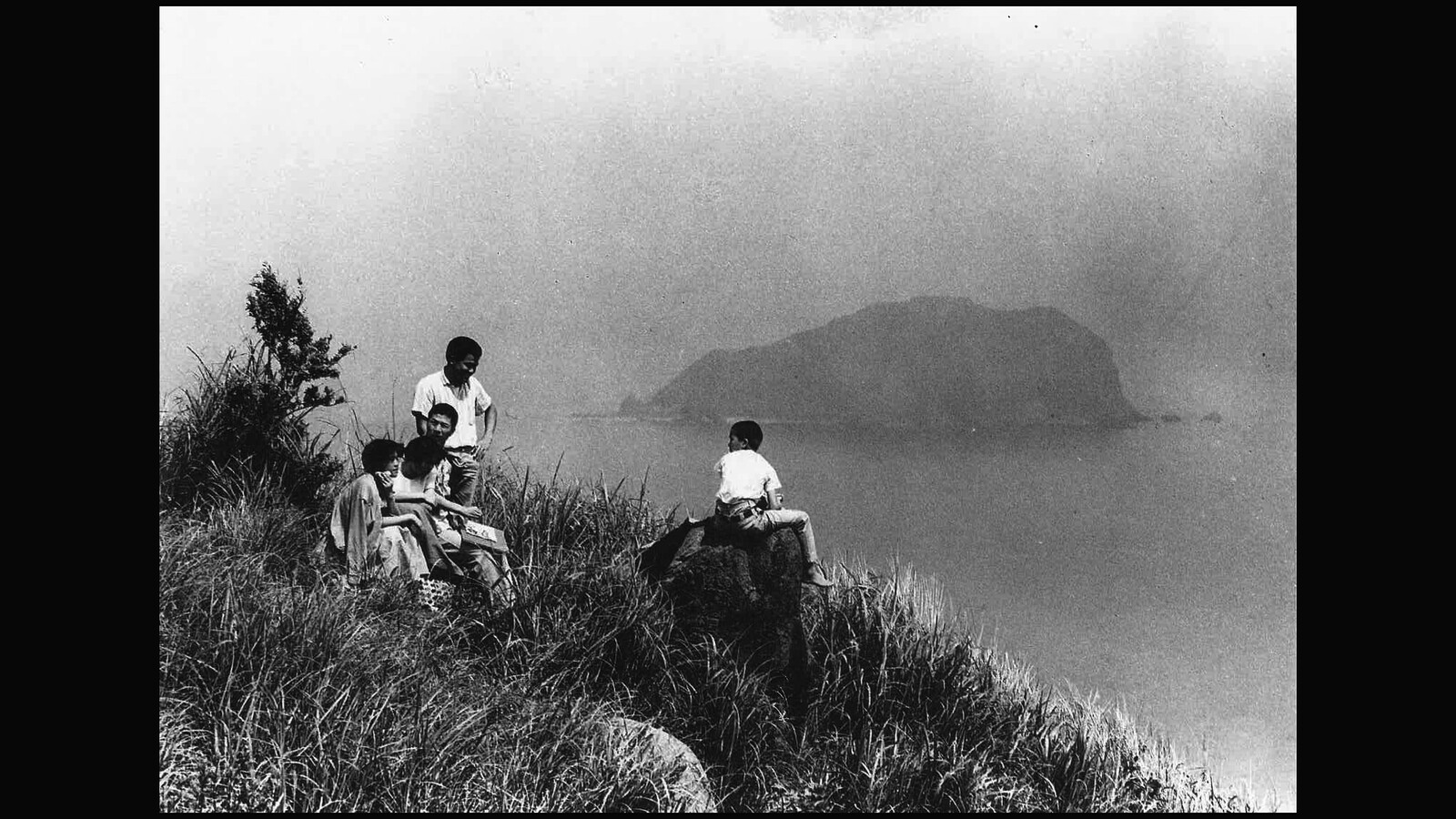

New Taipei City Art Museum

Interweaving Travelers

e-flux Announcement

Posted: November 8, 2023

Category

Globalization

Subjects

East Asia

Institution

National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC), Bucharest

Fall 2023/spring 2024 exhibitions

e-flux Announcement

Posted: October 28, 2023

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Futures, Exhibition Histories

M+, West Kowloon Cultural District

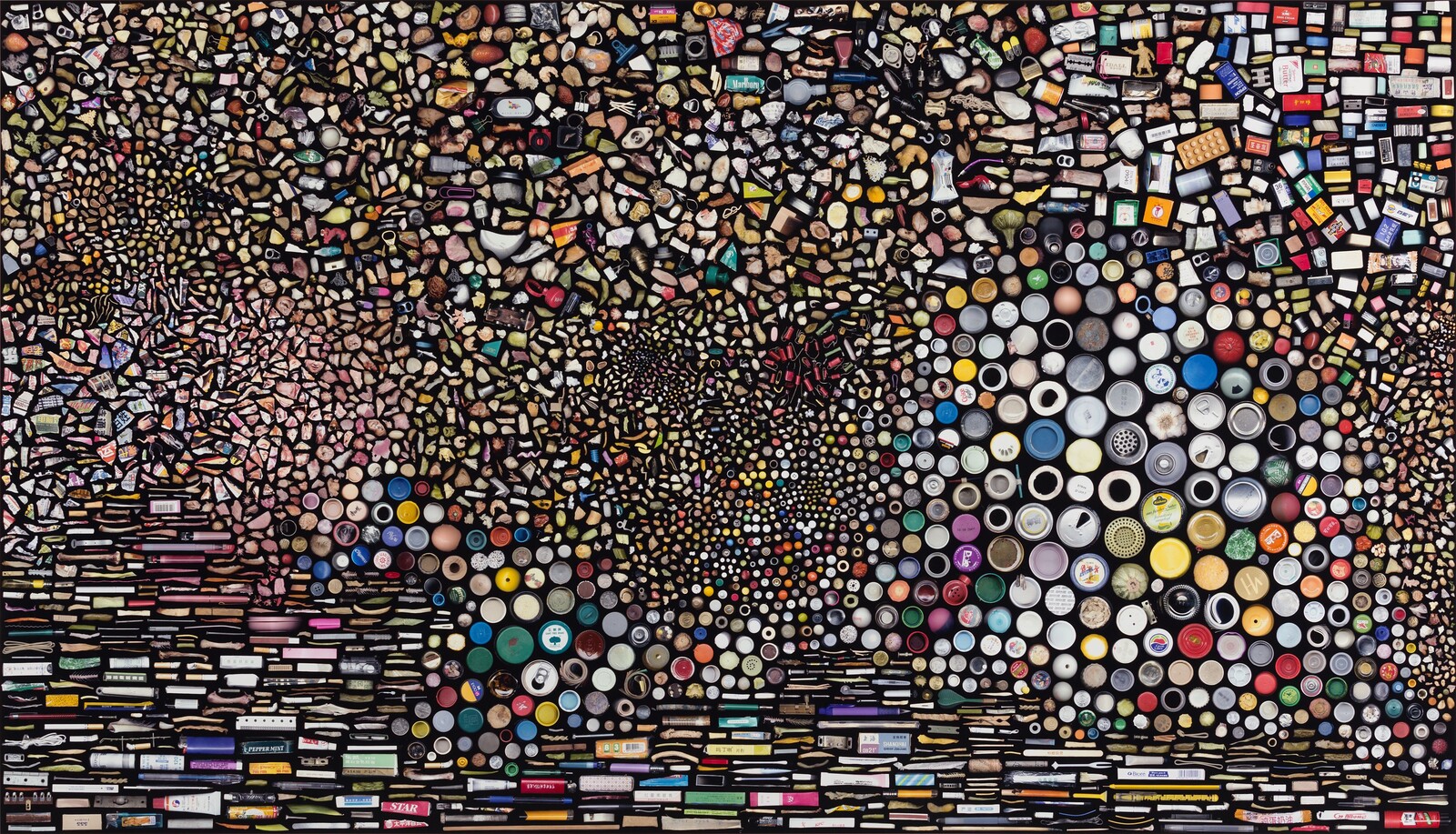

M+ Sigg Collection: Another Story / Sigg Prize 2023

e-flux Announcement

Posted: September 26, 2023

Category

Globalization

Subjects

China, Revolution

Institution

Walker Art Center

Allan Sekula: Fish Story

e-flux Announcement

Posted: August 24, 2023

Category

Globalization, Photography

Subjects

Water & The Sea, Documentary

Institution

Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR

SURREAL FUTURES

e-flux Announcement

Posted: August 8, 2023

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Surrealism, Virtual & Augmented Reality, Futures

Institution

Triennale Milano

Unseen Collaborations

Architecture Announcement

Posted: May 31, 2023

Category

Design, Globalization

Subjects

Industrialization

Institution

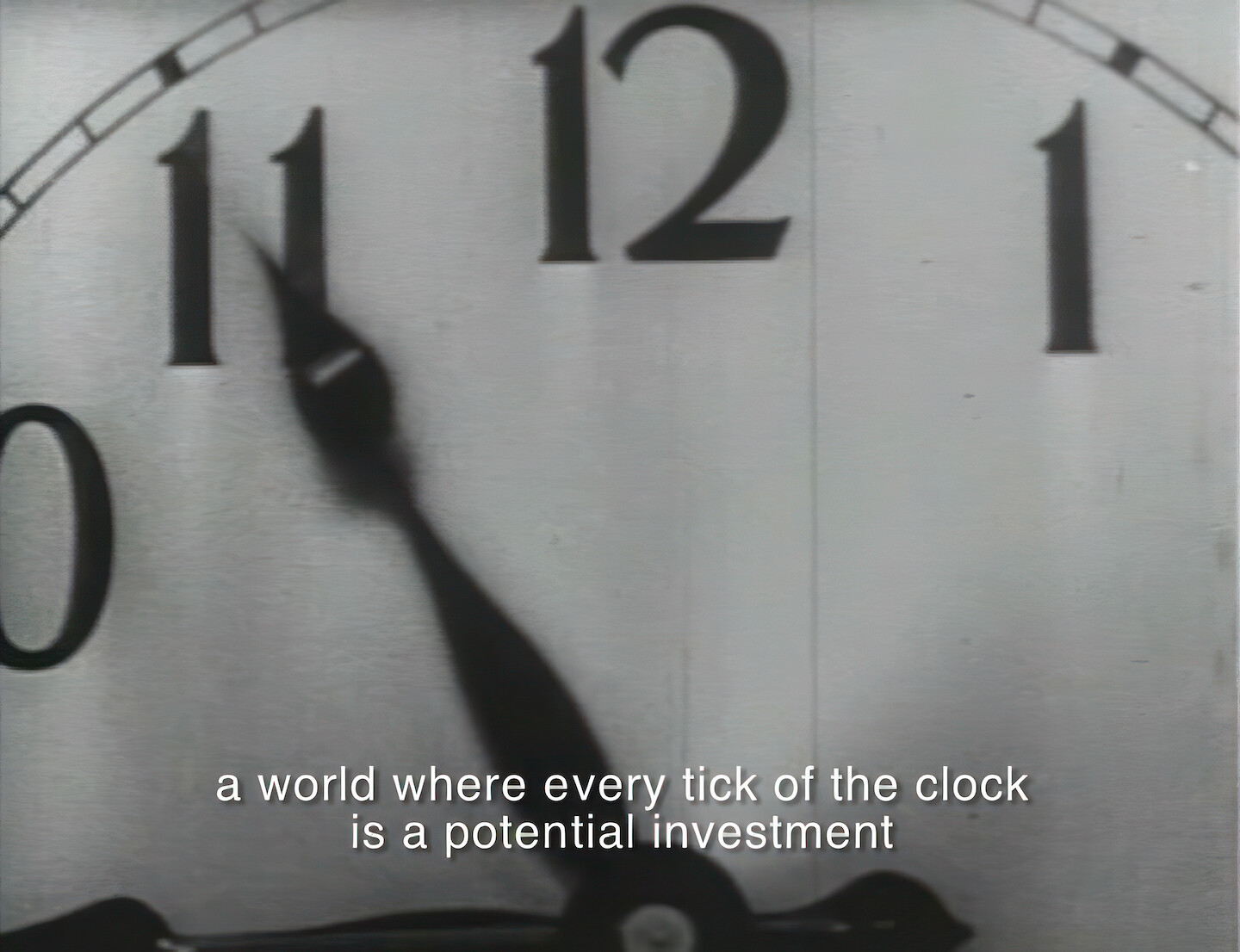

e-flux Events

Posted: May 20, 2023

Category

Film, Globalization, Labor & Work, Capitalism, Technology

Subjects

Time, Modernity

University of Cologne

The Entire Story Starts Where

e-flux Education

Posted: May 15, 2023

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Networks

Deichtorhallen Hamburg

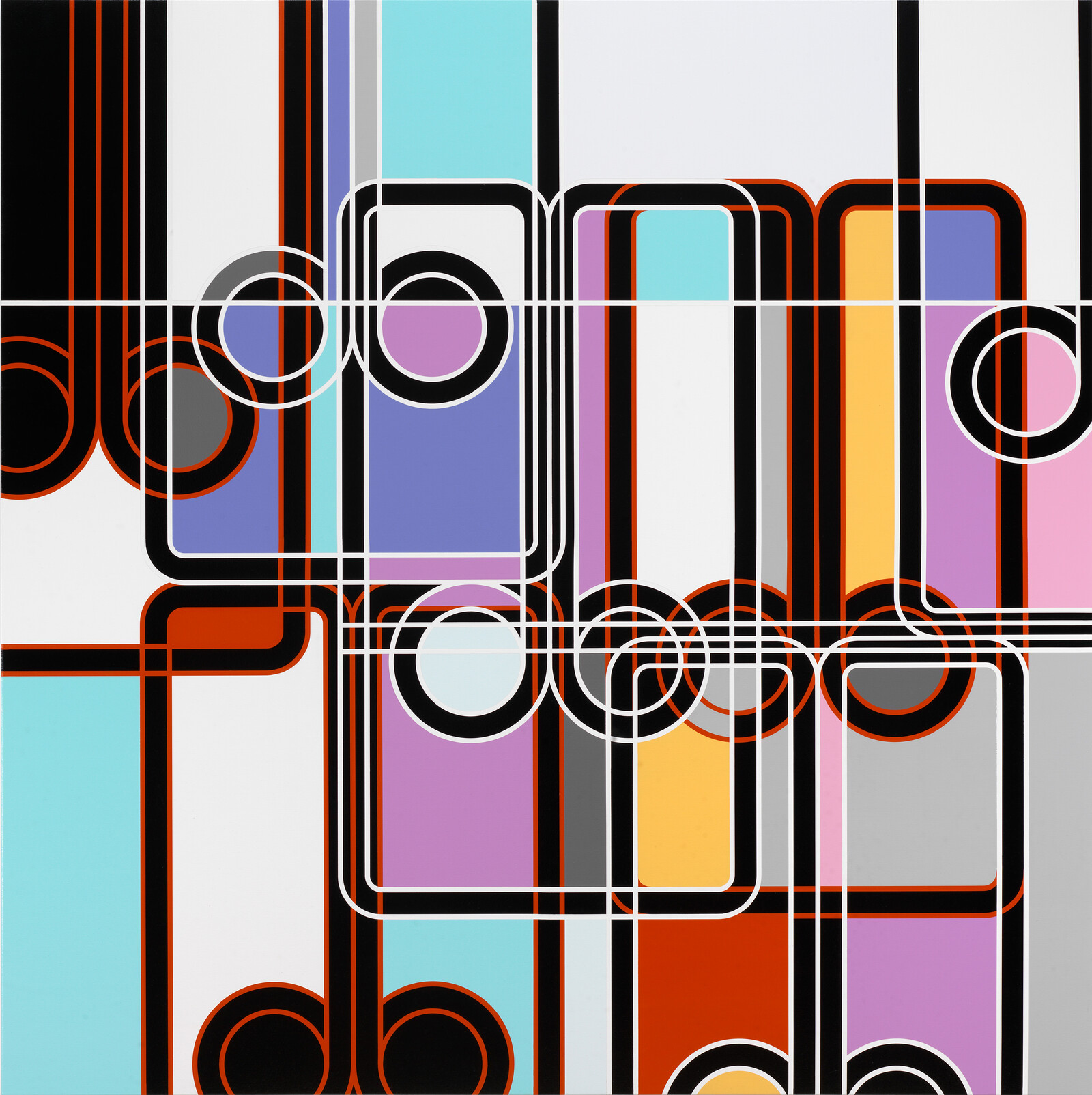

Sarah Morris: All Systems Fail

e-flux Announcement

Posted: May 4, 2023

Category

Painting, Urbanism, Globalization

Subjects

Video Art, Networks

Institution

Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei

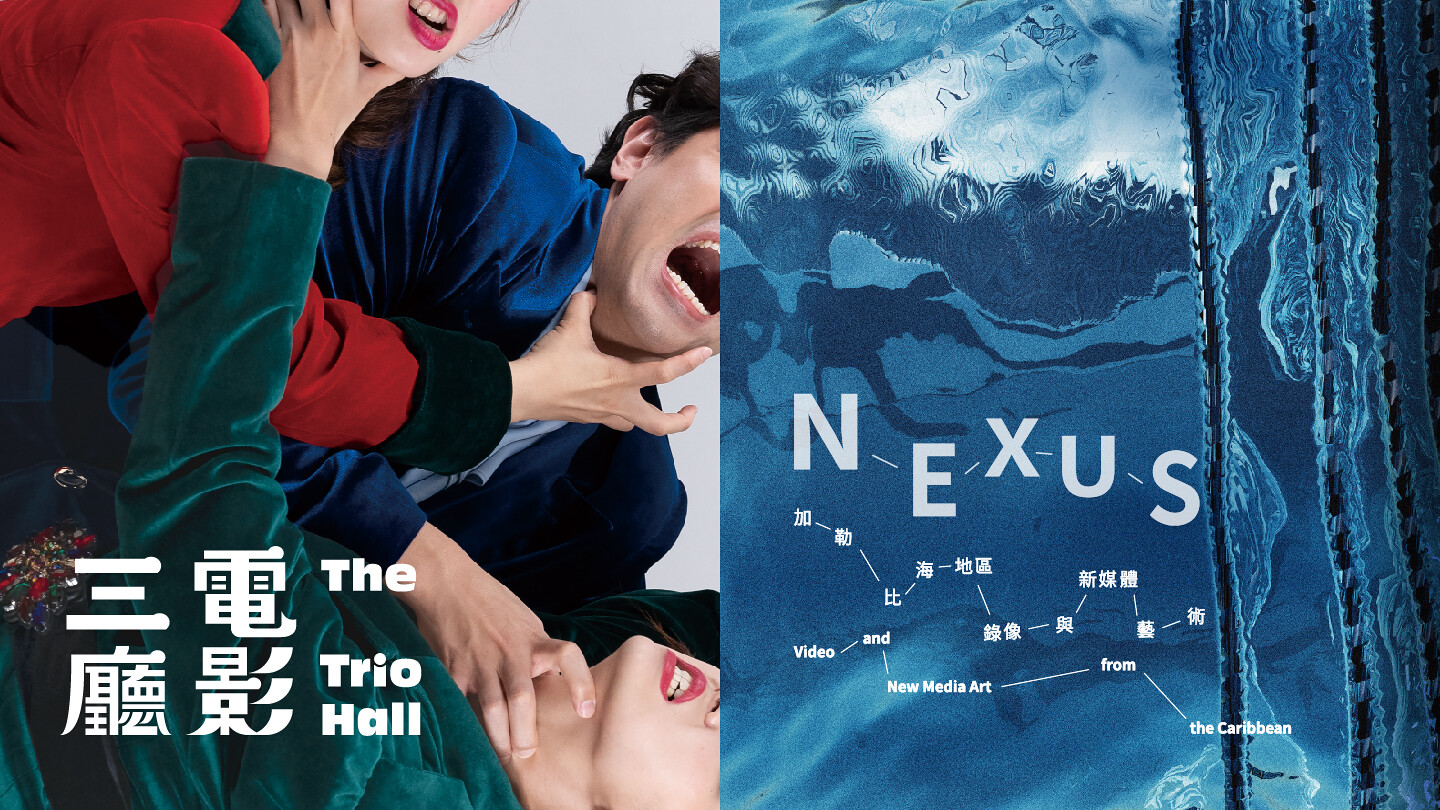

Su Hui-Yu: The Trio Hall / NEXUS

e-flux Announcement

Posted: May 1, 2023

Category

Globalization, Colonialism & Imperialism

Subjects

East Asia, Mass Media & Entertainment, Caribbean

Institution

e-flux Announcement

Posted: April 3, 2023

Category

Globalization, Technology

Subjects

Digital Humanities

Institution

e-flux Announcement

Posted: March 14, 2023

Category

Migration & Immigration, Globalization, Performance

Subjects

East Asia

Institution

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Call for research: Stedelijk Studies Journal issue 14

e-flux Announcement

Posted: March 7, 2023

Category

Borders & Frontiers, Globalization

Subjects

Neoliberalism

Institution

e-flux Film

Category

Film, Labor & Work, Globalization

Subjects

Video Art, Computer-Generated Art, Documentary

Van Abbemuseum

Rewinding Internationalism

e-flux Announcement

Posted: November 16, 2022

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Cold War, AIDS, History

Institution

Museum of Contemporary Art Skopje

All That We Have in Common

e-flux Announcement

Posted: October 25, 2022

Category

Globalization, Capitalism

Subjects

Multiculturalism, Identity Politics

Institution

Nieuwe Instituut

Vertical Atlas

e-flux Announcement

Posted: October 22, 2022

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Maps, Publications

Institution

Digestion Talks

Lydia Kallipoliti, Christina Moushoul, Meredith TenHoor, Anthony Vidler, and Lindsey Wikstrom

e-flux Events

Posted: October 17, 2022

Category

Architecture, Globalization

Subjects

Food & Cooking, Agriculture, Covid-19

e-flux Criticism

Posted: October 7, 2022

Category

Globalization

Subjects

Internationalism, Identity Politics

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

New collection presentation and program highlights 2022–2024

e-flux Announcement

Posted: September 17, 2022

Category

Avant-Garde, Globalization

Subjects

Everyday Life, Modernity, Multiculturalism

Institution