Economic theories and calculations shape the way societies construct value, which in turn structures architectural production, which in turn influences the environment.1 This is particularly evident in the impact that the economic concept of the “multiplier effect” had on the global advancement of post-WWII tourism and the architecture of hotels and resorts, especially in the “global sunbelt”—areas that based their economic growth not on industrial production but rather through the commodification of leisure and sunshine.2 Key to launching post-war tourism, the multiplier effect advanced the intensive reconstruction of coastlines, the proliferation of hotels and resorts, and the development of infrastructure.

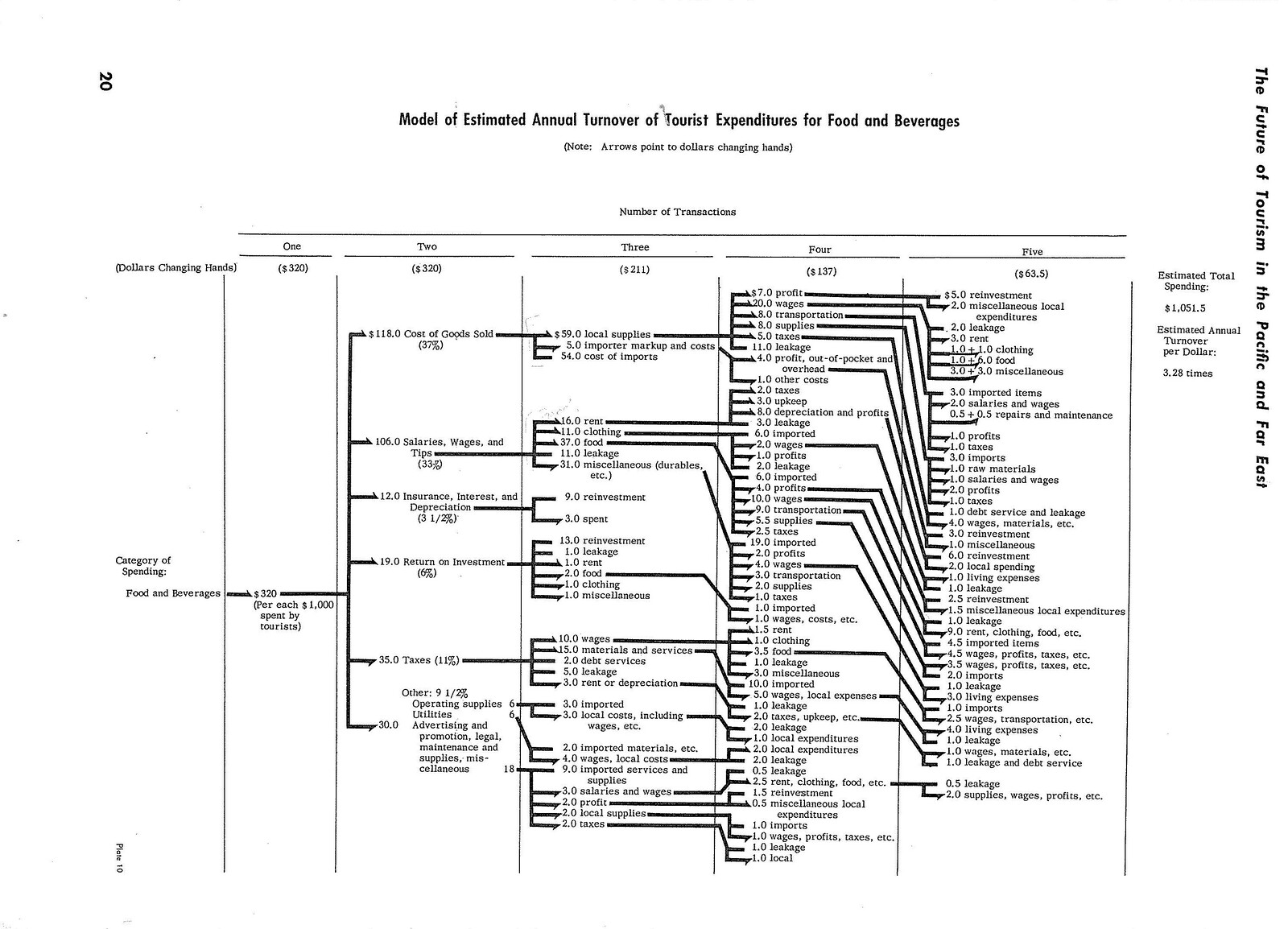

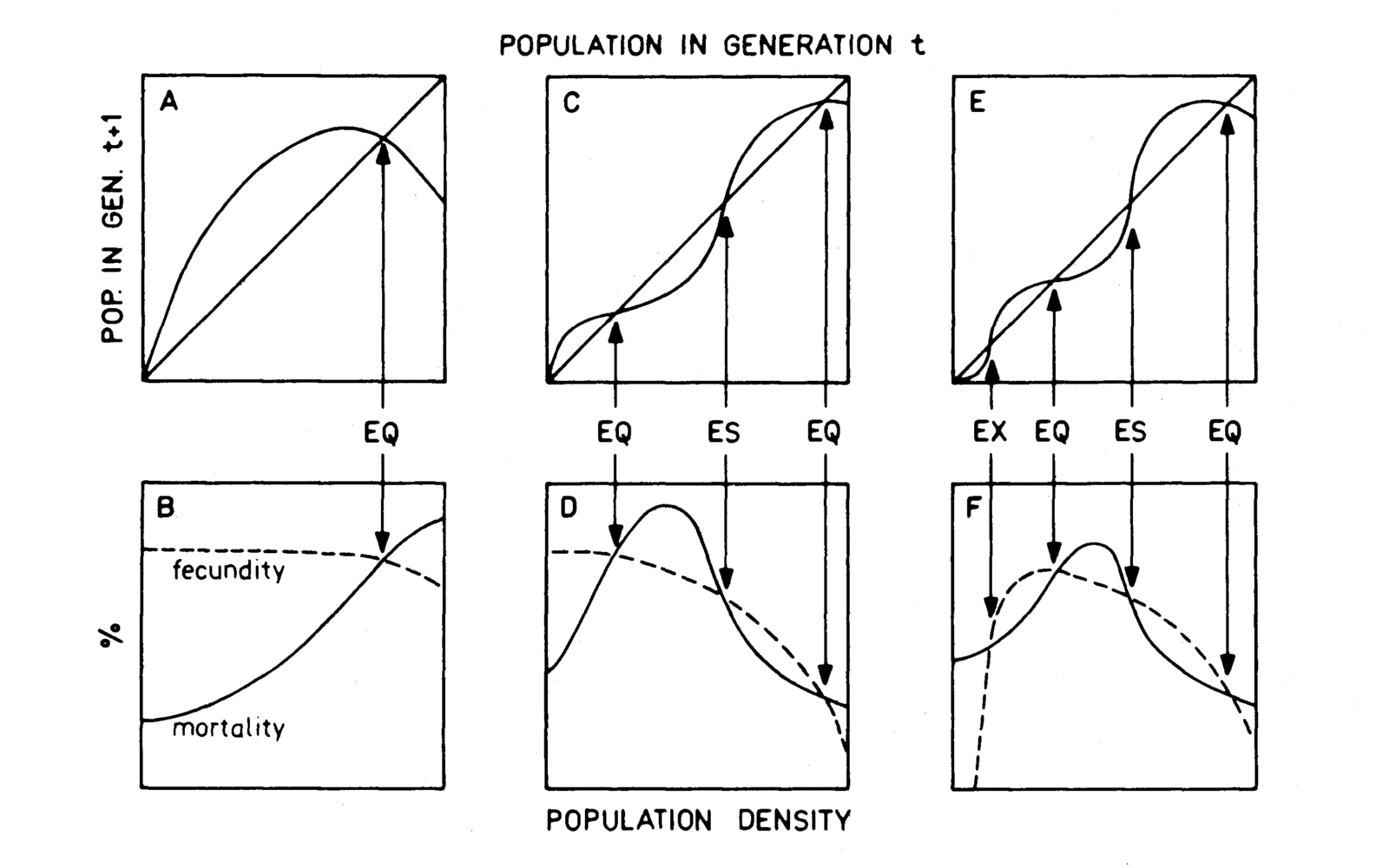

The concept of the “multiplier effect” shaped the ways in which national and international institutions and experts calculated the economic contribution of the tourism industry. It became the key rationale informing the formulation of tourism policies globally. The concept was first popularized in the tourism industry by the influential 1961 report The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and the Far East, also known as the Checchi Report.3 The multiplier effect represented a new way of quantifying the economic impact of tourist spending. Instead of measuring the exact expenditures by tourists, the economic calculus of the multiplier effect followed the circulation of tourist expenditures throughout the economy, and calculated both direct and indirect impacts. Premised on assumption that “[t]he more times [the tourist dollar] changes hands and the more times it is spent, the greater the economic impact,” the multiplier effect measures the turnovers per dollar expended by a tourist in a year.4

The Checchi report attributed the multiplier concept to the MIT economist Paul A. Samuelson’s 1939 multiplier-accelerator model.5 Using models of expenditures on different categories—including accommodations, food and beverages, purchases, sightseeing and amusement, and local transportation—the report argued that each dollar spent by a tourist had a multiplier effect ranging between 3.2 to 4.3 in the same year. The assumption was that a fraction of each dollar of tourist spending would go towards wages of the workers involved or costs of goods and services, which would then benefit other workers, importers, or distributors of goods, as well as service providers in the next round of transactions, which would all, in turn, have further cascading effects with additional rounds of transactions. The report also made the case that the 3.2 dollars of economic activity per tourist dollar spent meant that notions of national income and tax revenues from tourism, as well as the cost-benefit analysis of tourism promotion, should be calculated differently. Taxes and state investment should be based not just on direct expenditures but on indirect outlays and induced consumption estimated by the multiplier effect.6

The Checchi Report was sponsored by the United States Department of Commerce and the Pacific Area Travel Association (PATA). The former saw tourism development as a factor in building international understanding, and more importantly, as a source of national income. The promotion of tourism was aligned with United States Cold War-era foreign policy of “assist[ing] free nations in making the fullest possible use of their own resources in order that they remain economically viable and politically free.”7 The latter, PATA, was a nonprofit group established in 1952 to promote tourism in the Asia Pacific region that was initially based in Hawaii and, from 1953 onwards, in San Francisco.8 The report projected a quadrupling of tourist expenditure between 1958, when research for the report started, and 1968. It noted that “the economic impact of these expenditures could be spectacular,” and the report encouraged international and national institutions to promote tourism by, among other things, encouraging the development of tourism infrastructure.9 One of the key elements of this infrastructure was hotels. The report recommended that nations in Asia Pacific reduce, if not eliminate, taxes for investors in hotels, arguing that it would spur private investment, and that the tax rebate would be made up by tax revenues from the multiplier effect of tourist expenditures.

Before the Checchi Report, there was minimal interference by Asian Pacific governments in the development of tourism in the region. The Checchi Report changed that. Many of its recommendations were embraced by governments in the Asia Pacific, including the Philippines, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Korea, India, Taiwan, Thailand, and Malaysia. These governments all established official tourism organizations, drew up tourism development masterplans, and began to make major investments in tourism infrastructure such as airports and roads. They also created incentives to stimulate private investments in establishing “international standard” hotels. Most of these hotels were part of large international hotel chains such as Hilton, Grand Hyatt, and Intercontinental, many of which were headquartered in the US and linked to major airlines.10 National governments in the Asia Pacific typically worked in conjunction with PATA to promote tourism in their countries. Besides drawing on the expertise of PATA members to formulate national and regional tourism plans, they also staged annual PATA conferences as major events to showcase their tourist attractions. These events received extensive international media coverage and helped publicize Asia Pacific tourism from the 1950s onward.11 Through these combined efforts, tourist arrivals in the five Southeast Asian countries that adopted these policies grew by 560% between 1960 and 1970, and then another 500% in the following decade.12

The Multiplier Effect’s Global Spread

Although the Checchi Report was written specifically about Asia Pacific, its influence went beyond the region. The theory of the multiplier effect and its embrace in Asia Pacific countries helped paint a picture of tourism development to international governance and development organizations as a reliable means to increase national income and employment levels. Already in the 1950s, postwar US development aid to southern European countries was focused on tourism, and effectively turned agrarian economies such as Greece, Spain, and Turkey into international tourist destinations.13 However, it was not until the Checchi Report and the 1963 United Nations Conference on International Travel and Tourism that tourism was embraced and actively promoted by international institutions such as the World Bank, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and the Inter-American Development Bank as part of their development agendas in non-industrialized countries in the “Third World.”14 While these countries did not receive Marshall Plan aid, they were handed a model of tourism development that had been tested under the auspices of it. As such, national economies with “sun, sand, and sea” were encouraged to develop tourism as both an alternative to industrialization and a means to economic prosperity for political stabilization. Tourism was therefore effectively advanced as a proxy to the Marshall Plan.15

The World Bank, for instance, established a Tourism Development Projects Department (TPD) in 1969 together with the International Development Association (IDA), its soft loan subsidiary.16 In one decade, the TPD supported twenty-four projects in eighteen countries, with loans totaling US$450million. Eight of these projects were located in the Mediterranean basin, seven in Mexico and the Caribbean, six in Africa, and three in Asia.17 In Tunisia, in 1972, the World Bank approved a loan for funding extensive infrastructural projects in transport, energy, telecommunications, and sanitation, all on the basis of projected needs for tourist accommodation.18 In the same decade, the World Bank financed the construction of more than twenty hotel projects, the largest of which were located in Yugoslavia. For the World Bank and national governments, considerable investments in roads, airports, and other tourism infrastructures were seen as a modernizing force, one that also provided amenities for local populations. While creating jobs in construction and services, tourism increased the demand for local goods, crafts, and “local traditions,” engaging local populations in the creation of artefacts that would decorate hotels, products that would be sold in souvenir shops, or other goods that would feed the consumption drive on which tourism relies. The demand for new goods and services was expected to offer a quick way to improve the incomes and lives of subsistence farmers that formed the majority of many non-industrialized countries.

A telling example of the way tourism multipliers had a profound effect in shaping institutional cultures and building practices is the reinvention of Cyprus as a Mediterranean tourism hub. As early as 1962, just two years after the end of British colonial rule and one year after the original Checchi report for Asia Pacific, the same consultancy—Checchi and Company—published a report for the young Republic of Cyprus. Their report again highlighted tourism as a foreign exchange earner, intimately related to labor markets and the mobility of people and capital. The key recommendation of the Checchi report on Cyprus was the creation of the Cyprus Development Bank to facilitate financing from international lending institutions such as the World Bank, especially for development projects in tourism and services sectors.19 In doing so, the Checchi report tied Cyprus’s tourism development efforts to an international institutional culture that was shaped by the doctrine of the multiplier effect.

Up until that time, agriculture was Cyprus’s primary employment sector, whereas government revenues and foreign exchange earnings relied on copper exports and the economic activities of British military bases located on the island. The Checchi report found these inadequate to either advance economic development or increase jobs, and proposed a general shift towards manufacturing, processing industries, and tourism services.20 These recommendations were augmented by other Euro-American expert studies, and led the Cyprus government to decisively turn its focus towards the creation of hotels and invest in infrastructure that would support tourism.21 Up until the early 1960s, Cyprus was visited only by a couple of thousand people per year and had a few small-scale and family-run hotels, mostly in the interior of the country. This radically changed after the Checchi report, and by the mid 1960s, the construction of a government-funded Hilton Hotel and a brand-new airport terminal in the island’s capital were well under way. Coastal areas also began to be urbanized (and made ready for foreign tourists). By 1969, tourism was confirmed as a national priority and a fast-growing economic sector with the establishment of the Cyprus Tourism Organization and Cyprus Airways, and boosted by increasing arrivals and major private and state investments.

The widely accepted logic of tourism’s multiplier effect led to a radical transformation of the coast of Cyprus, starting with the construction of seaside hotels in the area of Varosha in the late 1960s.22 From 1967 to 1974—when development came to an abrupt halt due to political conflict—the sandy coastal area, which had previously been sparsely occupied by fishermen, a military camp, and a couple of low-rise recreation buildings, turned into an urbanized beachfront strip and a major destination for mass tourism.23 Without much in the way of planning ordinances or urban design principles, multi-floor hotels were quickly erected directly on the beachfront, commodifying the site’s abundant “sun, sea, and sand.” Facilitated by modern architecture’s propensity for standardization, seaside hotels and beach apartment buildings accelerated the inflow of tourists and foreign exchange. Celebrated as visible manifestations of a thriving economy and modernizing society, these infrastructures mediated—and effectively naturalized—tourism’s presumed positive effects on various sectors of the local economy, including the fast-growing construction industry.24

Problems created by hotel construction such as piling environmental costs, beach overpopulation, and the overuse of water and other resources already began to be recognized by local newspapers and responded to with popular protests in the early 1970s. Such critiques were typically hushed by both state and private embrace of the ostensibly positive socio-economic promises of tourism’s multiplier effects. Globally, however, studies emerging in the early 1970s also began to challenge the actual benefits of tourism multipliers on local economies, and further decried tourism’s social and environmental impacts.25 The international institutional climate also began to change around that time, with the UNDP supporting studies that highlighted tourism’s negative impacts, and calling for the need to balance tourism with the environment through proper state regulation and planning.26 The World Bank also stepped away from its enthusiastic embrace of tourism and phased out its Tourist Department in 1979.27 Despite the growing institutional ambivalence towards tourism development, the economic logic of its multiplier effect endured. It was well embedded in the bureaucratic and social practices it had instituted on global and local levels, which continued to justify growing demands for large hotels and to naturalize uneven access to common resources. It also tied the global industry of tourism to the fate of specific locales and their social and environmental crises.

Hotels in Drought-Stricken Cyprus

The promise of multiplying profits through the circulation of money, which would be activated by tourism development in general, and the multiplier in particular, had a profound impact on numerous ecological processes, but especially on water and hydrological cycles. To sustain their operations and the standards of luxury that were expected by international visitors, hotels often influence the circulation of water in ways that exacerbate local water consumption patterns, heighten dependence on large-scale water infrastructures, and in certain cases degrade and pollute water sources.

This became evident in Cyprus after 1974, when armed conflict and the division along ethnic lines limited the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus to the south part of the island. As tourism growth in Varosha and other areas was interrupted and major tourism infrastructure remained inaccessible north of the division line, tourism development in the south was embraced by the Republic of Cyprus as “a quick means of generating jobs and reactivating a shattered economy.”28 After 1974, tourism was heavily supported by the Cyprus Development Bank and its main creditor, the World Bank, to augment the economic practices that had been instituted in the 1960s: namely, low interest loans and tax incentives for hotel construction. As a result, along the southern coasts, bed capacity increased from 15,000 to nearly 60,000 in the decade between 1981 and 1990.29

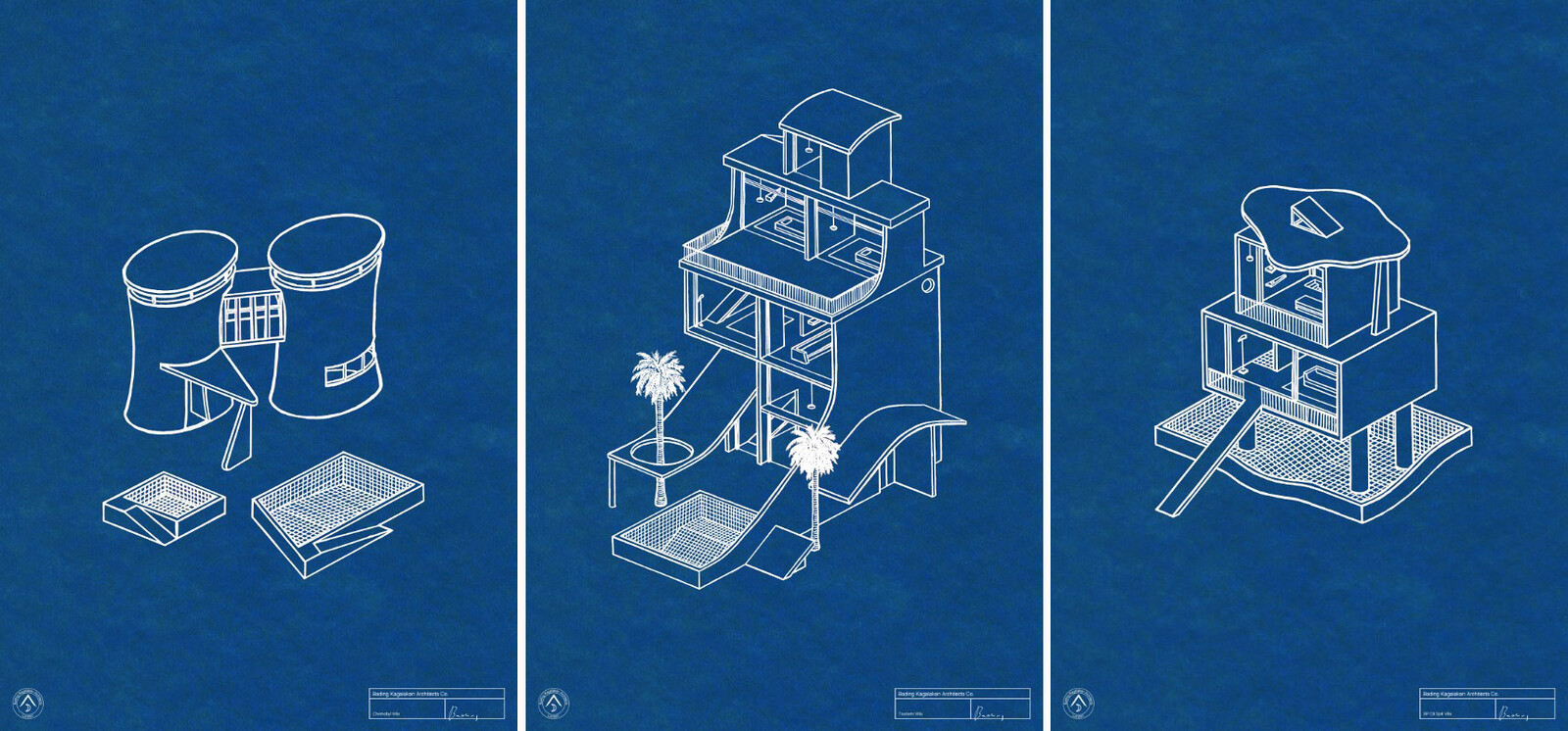

Hotels and resorts built in the south of Cyprus in the 1980s were not only orders of magnitude larger than the hotels of the 1960s; they also thematized and spectacularized natural elements, and in particular, water. Despite the fact that beachfront hotels and resorts continued to have the sea at their disposal, seaside hotels and resorts increasingly incorporated water fountains, lavish gardens, and large pools. This extravagance was instigated by the favorable treatment for hotels of unrestricted water consumption, even as locals were required to ration water due to perennial droughts. These water-intensive architectures only contributed to problems which were already intensifying by rising temperatures and more frequent droughts.

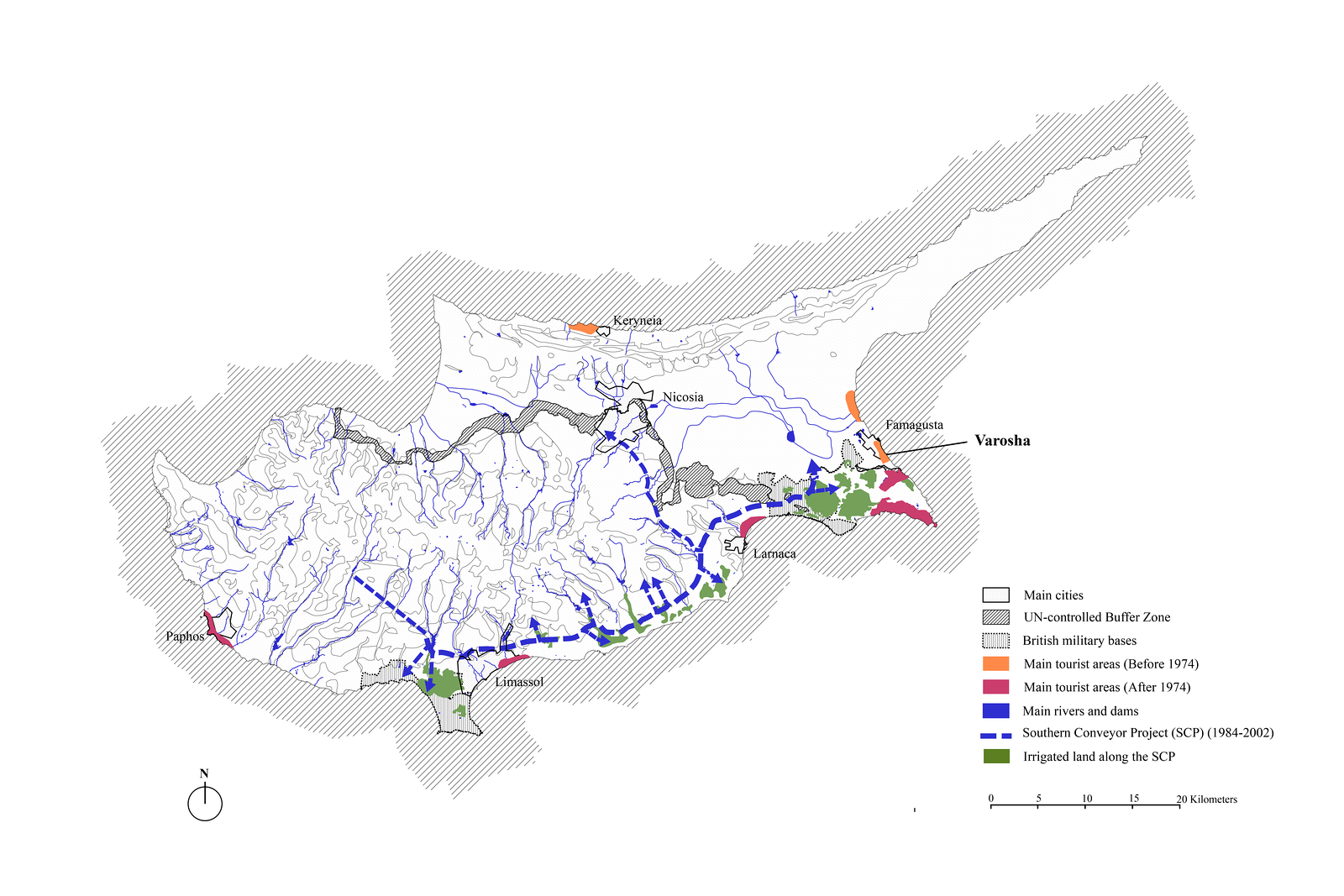

Map showing Cyprus’s 1974 division, the Southern Conveyor Project, and the competition (for water) between the overlapping zones of tourism and farming. Drawn by Michalis Psaras and Petros Phokaides.

In the early 1970s, private hotels and urban design projects constructed large-scale pools right on the coast. Salamis Bay Hotel, 1973, Salamina. Source: Economou Architects & Engineers, Digitization by Mesarch Lab, University of Cyprus, 2012.

Seaside hotels and resorts built on the southern coasts of Cyprus in the 1980s and 1990s developed water-intensive typologies of pools and lavish gardens, Source: Cyprus Geological Survey Department GEOportal. See ➝.

Map showing Cyprus’s 1974 division, the Southern Conveyor Project, and the competition (for water) between the overlapping zones of tourism and farming. Drawn by Michalis Psaras and Petros Phokaides.

The excessive use of this vital recourse in hotels and resorts inevitably increased the rationing of urban water and the restrictions on agriculture, which was already being hit hard by the loss of key water resources that existed in the north and the reshuffling of agricultural labor due to population displacements.30 As a result, illegal drillings for water increased, for the sake of both agriculture and hotel resorts, especially in the south-eastern part of the island which was both an important agricultural area and a popular tourism destination. All this ultimately led to the overuse of underground aquifers that created a vicious circle: the salinization of the soil added to local farmers’ problems, pushing agricultural workers to turn to the seemingly more “secure” jobs of an already overgrown tourism industry.

Even if they were seldom acknowledged in the local public sphere, the environmental problems of tourism in Cyprus were eventually noticed by international and local stakeholders. A UNDP Master Plan for Cyprus from 1988, which was made with the World Tourism Organization, prioritized “environmental protection,”31 while around the same time the president of the Cyprus Development Bank admonished that “the environment as a resource for tourism is a limited one… It has scarcity value.”32 In other words, tourism’s environmental consequences were taken into account to the extent that they could preserve Cyprus’s “tourist product” and keep international agencies and creditors satisfied. This perpetuated the inextricable ties of the tourism sector’s growth to the national economy, bureaucracy, and private investment interests.

By the mid-1980s, it was also becoming evident that Cyprus’s environmental costs were too severe to simply be managed through policy regulation, regional planning, and hotel-scale solutions such as water recycling and sewage treatment plants. The intense concentration of hotels and beach resorts on certain southern coastal strips of the island contributed to the disruption of the island’s hydrological cycle, which was in turn considered a restriction on tourism’s growth. This prompted a large-scale response for the creation of new infrastructures to ensure high-quality water to both hoteliers and farmers, especially in the southeast.33 Supported by the World Bank, the Southern Conveyor Project is the largest irrigation project to have ever taken place in Cyprus in terms of scale, complexity, and cost. Constructed in phases from 1984 to 2002, it included the construction of a major dam, the diversion of rivers, the construction of drinking and irrigation water treatment plants, and extensive irrigation networks.34 The overarching goal of the project was to transfer surplus rainwater from the less populated and less touristic regions of the southwest to the southeast and cover domestic water demands for other cities and villages along the way. All these expensive water infrastructures, reinforced Cyprus’s dependence on international funding and expertise and maintained a water-intensive economy on a drought-stricken island. These projects offered tourism the means to continue urbanizing the coasts, to eat up agricultural land, and to expand its physical footprint through golf courses, tourist villages, waterparks, and luxury villas, effectively multiplying its toll on waterscapes and other ecological processes.

View of the cascading swimming pools at Amankila, an exclusive resort in Bali. Photograph was taken in 1993 by Jiat-Hwee Chang.

Hotels and the Hydrological Crisis in Bali

Back in the Asia Pacific, rapid expansion of tourism infrastructure, especially hotels, took place from the 1960s to 2000. As in Cyprus, these developments had multiplier effects in both economic and environmental realms. Many of these repercussions are evident in Bali, a renowned tourist destination that is also an island – approximately half the size of Cyprus.35 Based on the recommendations in the 1961 Checchi Report, the Indonesian government introduced a number of policies and initiatives in the late 1960s intended to promote tourism development in Bali. These included tax incentives to encourage foreign investment in hotel construction, building of a new international airport and road infrastructure that was funded by the World Bank, commissioning a French consultant group to produce a new tourism masterplan (1971), and hosting the high profile PATA conference in 1974 to promote Bali as a tourism destination.36

Tourism development in Bali from the late 1960s brought about extensive changes in land use patterns. While the 1971 masterplan only allocated three zones on the island for tourism development, the rapid expansion of tourism in the following decades led the number of tourism zones to be increased to twenty-one.37 The expansion of hotels and other tourism developments in Bali also fueled waves of real estate speculation. In the beginning, the focus was on beachside properties, many of which were originally left uninhabited by locals— in traditional Balinese cosmology they were regarded as spaces unsuited for human habitation.38 Later, development interests expanded to other sites, including farmlands. By the 1990s, an estimated 1,000 hectares of arable land per year was converted to tourism-related uses. As a result, Bali lost around one quarter of its agricultural land between the 1990s and mid-2010s.39

Balinese hotels and resorts are, as in Cyprus, known for their water-intensive features. Balinese resorts even have a particular style that was “invented” by a group of expatriate designers and artists between the 1960s and 1980s. Today they are known for their lush gardens and luxurious water features such as infinity edge pools and outdoor baths, which purportedly let visitors indulge the sensorial delight of outdoor living in the tropics.40 This water-hungry infrastructure radically altered the traditional agro-ecology of Bali and its water management system, as well as its the larger hydrological cycles. As in Cyprus, water was redirected from agricultural uses to serve hotels and resorts, which together with other tourism developments has been estimated to consume 65% of all water in Bali.41 Even then, piped water was unable to meet the demands of these hotels and resorts, many of which illegally dug deep wells to extract groundwater. The over-consumption of piped water and the over-extraction of groundwater has led to insufficient potable water for Balinese residents and created public health issues stemming from drinking sub-quality water. The conversion of large amounts of agricultural land to tourism development also significantly altered drainage patterns, disturbing the hydrological cycle and leading to more flooding. Inadequate regulation of waterfront development also contributed to severe beach erosion in parts of the island.42

Conclusion

The impact of tourism development on water ecologies in Cyprus and Bali articulates a connection between broader environmental problems and the economic concept of the multiplier effect. Both postcolonial islands embraced in the early 1960s when they adopted economic recommendations from the Checchi company and global institutions that advanced this theory. Cyprus and Bali are not isolated cases. Tourism is the key sector on which many countries of the Global Sunbelt relied to build their economies; it also created numerous environmental problems. Although they began to surface at the end of the 1970s, these environmental problems have endured along with (or perhaps because of) tourism’s presumed multiplier effect. As this theory continued to be celebrated and implemented, focusing on the economic gains in “supply chains”—thus considering only who and what provided the labour and goods in different tourism services—came at the expense of the costs it has on ecological processes. The multiplier effect’s fundamental assumption that more tourists and more spending leads to more growth for the local economy created mirrored sequence: more hotels and infrastructures multiply resource abuse, which in turn exacerbates environmental problems.

The charm of the multiplier effect proved quite insidious. It led governments, international agencies, and global investors to perceive tourism in economic terms of capital flows, while the environmental costs of this model were creeping in steadily. And like the promise of economic multipliers, the environmental costs of radically changing water flows has a cascading effect. More importantly, Cyprus and Bali show that environmental problems were not a mere “externality”—a term often used to call for better planning and management and to entertain criticisms of tourism projects. The exhaustion of resources and the radical tampering with hydrological processes was not an “unintended consequence” of the proliferating hotels. Rather, the unprecedented commodification and domestication of water that tourism advanced ultimately naturalized this excessive consumption and waste to the extent that it changed hydrological cycles. By exacerbating the unevenness of the access to water, between farmers and hoteliers, or between locals and visitors, the multiplier’s claim that the gains of tourism would reach out to all ultimately falls apart.

Daniel M. Abramson, Obsolescence: An Architectural History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative, ed., Architecture in Development: Systems and the Emergence of the Global South (New York: Routledge, 2022).

See Sibel Bozdoğan, Panayiota Pyla, and Petros Phokaides, “Introduction,” Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt (New York: Routledge, 2022), xix- xliii. This book exposes cases of how leisure tourism radically transformed physical landscapes, from sandy beaches to littoral roads and marinas, and from beachside hotels, to camp sites, and vacation villages; and how it also reshaped social and geopolitical landscapes (from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea and Baltic coasts; and from California and the Caribbean to Southeast Asia).

Harry G Clement and Checchi and Company, The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and Far East (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1961); Chuck Y. Gee and Matt. Lurie, eds., The Story of the Pacific Asia Travel Association (San Francisco, CA: Pacific Asia Travel Association, 2001), 69.

Clement and Checchi and Company, The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and Far East, 18.

Characterized as a figure who “personified mainstream economics in the second half of the twentieth century… {and was} considered the incarnation of the economics ‘establishment,’” Samuelson combined Milton Keynes’s concept of the multiplier as an increase in total national income induced by governmental spending with Alvin Hansen’s acceleration principle to determine the relationship between governmental deficit spending and induced private consumption and private investment. Samuelson turned that relationship into a formula and provided a way to quantify the factor of multiplication. Paul A. Samuelson, “Interactions between the Multiplier Analysis and the Principle of Acceleration,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 21, no. 2 (1939): 75–78, https://doi.org/10.2307/1927758. See also: William A. Barnett, “An Interview with Paul A. Samuelson,” Macroeconomic Dynamics 8, no. 04 (September 2004): 519, ➝.

Clement and Checchi and Company, The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and Far East, 18–28. See also Habibullah Khan, Chou Fee Seng, and Wong Kwei Cheong, “Tourism Multiplier Effects on Singapore,” Annals of Tourism Research 17, no. 3 (January 1, 1990): 408–18, ➝.

Foreword by Luther H. Hodges, the US Secretary of Commerce in Clement and Checchi and Company, The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and Far East, iii.

Gee and Lurie, The Story of the Pacific Asia Travel Association; PATA, “This Is PATA: A Summary of 40 Years of Progress,” in AMIC-PATA Asian Tourism Communicators Training Workshop (Singapore: Asian Media Information & Communication Centre, 1992).

Clement and Checchi and Company, The Future of Tourism in the Pacific and Far East, xiv.

Robert E. Wood, “Tourism and Underdevelopment in Southeast Asia,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 9, no. 3 (January 1979): 274–87, ➝; James E. Potter, A Room with a World View: 50 Years of Inter-Continental Hotels and Its People: 1946-1996 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996).

In the two decades from the mid-1950s, PATA conferences were held in Asian countries including the Philippines (1954 and 1971), Japan (1956), Singapore (1959), Hong Kong (1962 and 1977), Indonesia (1963 and 1974), Korea (1965 and 1979), India (1966 and 1978), Taiwan (1968), Thailand (1969), and Malaysia (1972). Khir Johari, the Minster of Trade and Industry of Malaysia who led the organization of the 1972 PATA conference in Malaysia noted that the conference helped to “project Malaysia’s image to the world of Tourism.” PATA in Malaysia, 1972 (Kuala Lumpur: Dept. of Tourism, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Kuala Lumpur, 1972), u.p. For a list of the conferences, see Gee and Lurie, The Story of the Pacific Asia Travel Association.

These five countries are Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Johannes C. Franz, “The Seaside Resorts of Southeast Asia (Part One),” Tourism Recreation Research 10, no. 1 (January 1, 1985): 17, ➝.

See for example, Gökçeçiçek Savasır and Zeynep Tuna Ultav, “Mobility, Modernity, and Hospitality: TUSAN Tourism Initiative in Postwar Turkey,” in Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt, eds. Sibel Bozdoǧan, Panayiota Pyla, and Petros Phokaides (London, New York: Routledge, 2022): 215-231; José Vela Castillo, and Sıla Karatas, “Transnational Experts and the Architecture of Tourism Industry in Francoist Spain,” in Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt, eds. Sibel Bozdoǧan, Panayiota Pyla, and Petros Phokaides (London, New York: Routledge, 2022): 151-166; Stavros Alifragkis, and Emilia Athanassiou. “Educating Greece in Modernity: Post-War Tourism and Western Politics,” Journal of Architecture 18, no. 5 (2013): 699–720.

In 1963, the United Nations Conference on International Travel and Tourism recommended to UN specialized agencies, regional economic commissions, and member state governments—especially the ones in “developing countries”—to actively develop tourism and international travel. These recommendations relied on the economic report prepared by UN’s consultant Kurt Krapf who cited extensively the 1961-Checchi report and analysed the multiplier effect of tourism. See, United Nations Conference on International Travel and Tourism, Rome, 21 August - 5 September 1963: Recommendations on International Travel and Tourism (New York: UN, 1963); Kurt Krapf, Tourism as a Factor in Economic Development: Role and Importance of International Tourism (New York: UN, 1963).

See Panayiota Pyla, “Leisure and Geo-economics: The Hilton and Other Development Regimes in the Mediterranean South,” in Systems and the South: Architecture in Development, ed. Aggregate (Arindam Dutta, Ateya Khorakiwala, Ayala Levin, Fabiola López-Durán, and M. Ijlal Muzaffar) (London: Routledge, 2022), 381–400.

Dimitris Ioannides, “Planning for International Tourism in Less Developed Countries: Toward Sustainability?” Journal of Planning Literature 9, no.3 (February 1995): 237; See also, Douglas G. Pearce, Tourist Development (New York: Longman, 1989).

H. David Davis and James A. Simmons, “World Bank Experience with Tourism Projects,” Tourism Management 3, no. 4 (December 1982): 212–17, ➝.

Ibid., 214.

Checchi and Company, Report on the Establishment of a Development Bank in Cyprus (Washington: Department of State: Agency for International Development, 1962).

Ibid, 2.

See Panayiota Pyla and Dimitris Venizelos, “Towers on a Golden Coast: Competing Visions of Development on Famagusta’s Beach”, in Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt, eds. Sibel Bozdoǧan, Panayiota Pyla, and Petros Phokaides (London, New York: Routledge, 2022): 133-151.

The multiplier effect was well received in Cyprus at the time. It was used by the Greek-based planning firm Doxiadis Associates in a major tourist study, titled: Future Development of Tourism in Cyprus, March 1968, commissioned by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Republic of Cyprus.

Throughout the 1960s there were serious episodes of ethnic inter-communal conflict among Greek and Turkish Cypriots and on top of that existed a civil strife within the Greek Cypriot community. It was exacerbated after 1967 when a military Junta in Greece came to power and began supporting paramilitary groups against Cyprus president Makarios. All this eventually led to a coup d’état in July 1974, which in turn led to a Turkish invasion and the division of the island along ethnic lines, up to this day.

See, Panayiota Pyla, and Petros Phokaides. “‘Dark and Dirty’ Histories of Leisure and Architecture: Varosha’s Past and Future.” Architectural Theory Review 24, no. 1 (2020): 27–45, ➝.

John Bryden and Mike Faber, “Multiplying the Tourist Multiplier,” Social and Economic Studies 20, 1 (March, 1971): 61-82.

Emanuel de Kadt, ed., Tourism: Passport to Development? (Oxford: Oxford University Press for UNESCO and World Bank, 1979).

Behind this decision were the implementation challenges and limited economic success of the tourist projects with which the Bank became involved, the turbulent economic climate after the 1973-oil crisis, but also the rising awareness of tourism’s social and environmental impact. H. David Davis and James A. Simmons, “World Bank Experience with Tourism Projects,” 212.

Dimitris Ioannides, “Planning for International Tourism in Less Developed Countries: Toward Sustainability?”, 10.

Kerry B. Godfrey, “The Evolution of Tourism Planning in Cyprus: Will Recent Changes Prove Sustainable?”, Cyprus Review 8, no. 1 (1996): 111-133.

In Cyprus, for years, urban water was heavily rationed, and water for irrigation was so limited that the state incentivised the abandonment of traditional agricultural production (such as citrus trees) because they were more water intensive.

UNDP and World Tourism Organization, Comprehensive Tourism Development Plan: Cyprus: Final Report. (Madrid: UNDP: World Tourism Organization, 1988).

Cited in Lois Jensen, “Cyprus: Boom in Tourism, Battle on the Environment.” World Development 2 (1989): 13.

For a detailed analysis, see Serkan Karas and Panayiota Pyla, “Promise of Water Abundance and the Normalisation of Water-Intensive Development in Cyprus,” Water Alternatives 15, 3 (2022): 709-732.

This was an extension of a state and UN-led program of dam construction launched island-wide after the country’s independence that was premised on water-intensive approach that served the exploitation and consumption rather than protection of scarce resources. See Panayiota Pyla and Petros Phokaides, “An Island of Dams: Ethnic Conflict and Supra-National Claims in Cyprus,” in Water, Technology and the Nation-State, ed. Filippo Menga and Erik Swyngedouw (London and New York: Routledge, Earthscan from Routledge, 2018), 115–130.

Much has been written about tourism development in Bali. See, for example, Jiat-Hwee Chang, “The Anaesthetics of Tourism: Bali, Internationalism, and Post-Conflict Developments,” in Coastal Architectures and Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt, ed. Panayiota Pyla, Sibel Bozdoğan, and Petros Phokaides (London, New York: Routledge, 2022), 36–51.

Michel Picard, Bali: Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture, trans. Diana Darling (Singapore: Archipelago, 1996); Adrian Vickers, Bali, a Paradise Created (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2012).

Jeff Lewis and Belinda Lewis, Bali’s Silent Crisis: Desire, Tragedy, and Transition (Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 2009), 55–59.

Raymond Noronha, “Paradise Reviewed: Tourism in Bali,” in Tourism: Passport to Development?, ed. Emanuel de Kadt (Oxford: Oxford University Press for UNESCO and World Bank, 1979), 177–204.

Lewis and Lewis, Bali’s Silent Crisis, 54; Ruben Rosenberg Colorni, Land Grabbing in Bali: A Research Brief (Amsterdam: Hands on Land for Food Sovereignty and Transnational Institute, 2018), 7.

Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava, “Cultivating Bali Style: A Story of Asian Becoming in the Late 20th Century,” in Southeast Asia’s Modern Architecture: Questions in Translation, Epistemology and Power, ed. Jiat-Hwee Chang and Imran bin Tajudeen (Singapore: NUS Press, 2019), 85–111; Philip Goad, Architecture Bali: Architectures of Welcome (Sydney: Pesaro Publishing, 2000); Made Widjaya, Modern Tropical Garden Design (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2007).

Stroma Cole, “A Political Ecology of Water Equity and Tourism: A Case Study from Bali,” Annals of Tourism Research 39, no. 2 (April 2012): 1221–41, ➝.

Lewis and Lewis, Bali’s Silent Crisis, 54–70.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)