In 2007, Turkish sociologist Şerif Mardin proposed the term “mahalle baskısı”—which translates as “community pressure” or “peer pressure,” and which refers to the practice of neighborhoods policing themselves—to describe a common experience in urban Turkey today: a clash of intolerance between secular Turkish society and Islamic lifestyle. With the rise of right-wing forces all over the world, mahalle baskısı can be found in many places—wherever conservatism and patriarchy reign. This leads to a new danger, in which two kinds of policing combine: mahalle baskısı and “algorithmic-design,” which is self-design mediated by algorithms for the collection of user data, the production of brand value, and surveillance. As an potential response to this danger, Boris Groys’s original conception of self-design can be empowering, though given the more complicated nature of self-design today, we will have to go further.

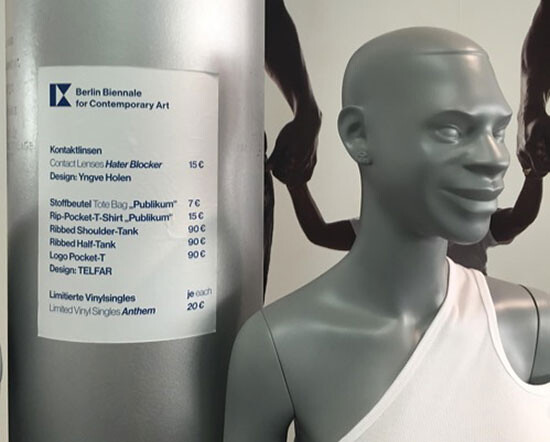

What is an artist to do? With an understanding of how our content, identities, and influence are valuable to and instrumentalized by brands and marketers, we can find space for resistance and refusal, or we can actively engage with existing models in an effort to ameliorate them. While it might seem like the only options are to ramp up your posting with accelerationist fervor, or delete your account, there are tactics to be learned from internet trolls, the alt-right, and institutional critique that can open space for effective critique and resistance.

Add this to Joyce’s famous passages detailing the sense of a frying kidney and, at the other end, a trip to the outhouse. Maharaj argues that Joyce offers information to all of the senses in a way that “cuts across” the mind/body dualism. Artistic research is located not in digestion itself but in an overlying wordplay; language turned against language. Such research is immanent in the artist, physically and abstractly, the way food is immanent within the body—and the way an artist like Raspet is immanent within a corporation like Soylent. Or the way art is immanent not in the can of shit but in the artist’s (say, Manzoni) signing such a can.

The way in which those who provision, discuss, and consume coffee accrue and emanate Bourdieuian distinction is fairly intuitive to anyone who has lived through the diffusion of the Starbucks brand from Seattle-based upscale cafe in the 1990s to the interstate rest-stop parody fodder of today. But the way in which the linguistic production of lifestyle variables emerges dialectically with co-occurring visual and material cues is less easy to discern. It is not altogether clear how our expectations around speaking about comestibles align qualitatively with our tastes for them, or the images we create around them.

Trend reports are a vehicle for identifying emerging behaviors and the forces that motivate them. We issued our own because we wanted our community of peers to be aware of the strategies that were being used on them as consumers, and that they were parroting back in their own artistic and creative practices. Trend forecasting is a form of armchair sociology that identifies how consumers respond to global sociopolitical and environmental change through pattern recognition. Trends are less about seasonal colors, and more about consumers’ crisis response. Our thought was that the more people are aware of these strategies, the more they can develop tactics based on those strategies and use them towards their own ends, whether in their studio practice or in their plan for survival on earth.