George Kafka Can you explain the genesis of FICA and, in simple terms, how the model works?

Renato Cymbalista (FICA) Around four years ago some people who were like me—white and middle-class—started to discuss and figure out what could be done to effectively address gentrification in São Paulo. We knew the answer had to do with real estate and had to do with money. We formed a non-profit association that would essentially act as a crowd-sourced fund or purse. With that fund, we buy property in downtown São Paulo and we rent it at non-speculative prices. People support us on a monthly basis or one-off donations. It’s a long-term project. When it started, we thought we would be buying our first apartment in five years’ time, but it went more quickly than we thought. In the beginning, a couple of the founders of the association donated an apartment. Our official name is Community Property Association, but we thought we would need a sexier name so we invented FICA: Fundo Imobiliário Comunitário para Aluguel (Community Real Estate Fund for Rentals).

GK So the people who are donating, they are doing this purely out of the kindness of their heart, to put it crudely?

FICA Definitely. They’re doing it because they believe in it.

GK To step back and briefly look at the wider context, what form does gentrification take in São Paulo?

FICA There has been a lot of talk about gentrification in São Paulo since the 1990s. Around 2002, a very famous text by Neil Smith, called “Gentrification Generalized” 1 was translated into Portuguese. He understood that gentrification was happening all over the world. Downtown areas in Brazil were quickly losing people after years of inflation and the aging of the housing stock. When the 2000 census in São Paulo was published, it was shocking to see that the downtown area was losing population while the periphery was rapidly growing.

GK When you talk about the periphery, are you referring to exclusive gated enclaves or to lower-income neighborhoods?

FICA No, these were poor people. The 1980s and 1990s had a perverse effect on the social occupation of the city; the rise of violent crime led to a general deterioration and abandonment of the city center. In the early 2000s, an interest in downtown was renewed. One association, called Associação Viva o Centro, was calling for downtown São Paulo to be renewed, made nice for the middle classes, for foreign entrepreneurs, for tourism, for cultural and government institutions. There were a couple of renovations of very fancy buildings like Sala São Paulo, home of the state symphonic orchestra. At the same time, social movements for housing and progressive NGOs and urbanists were resisting these projects. We saw the downtown area as an opportunity for poor people, since there was so much vacant property there and real estate prices were relatively low. From 2008–2009 there was a real estate boom, and we started to talk about gentrification in a more empirical way. Poor people were being priced out and evicted; new things that were being built were not being occupied by the lower-middle classes and the poor. That said, gentrification in São Paulo did not happen and probably will not happen exactly as it has in London or New York. There are still plenty of poor people living in downtown areas, but there is much more informality. There are many overcrowded tenement houses, what we call cortiços. They are only still there because they pay huge amounts in rent.

GK São Paulo’s downtown area is also occupied by tens of thousands of homeless people. Is this the population the FICA model aims to address?

FICA No, our model of housing requires that the tenant has a certain amount of income. This means that a lot of people don’t fit into our model. The monthly cost of our apartment for a family is R$633. You cannot find anything that cheap in downtown on the market. The apartment is 47 square meters, and a family of five people is currently living happily there.

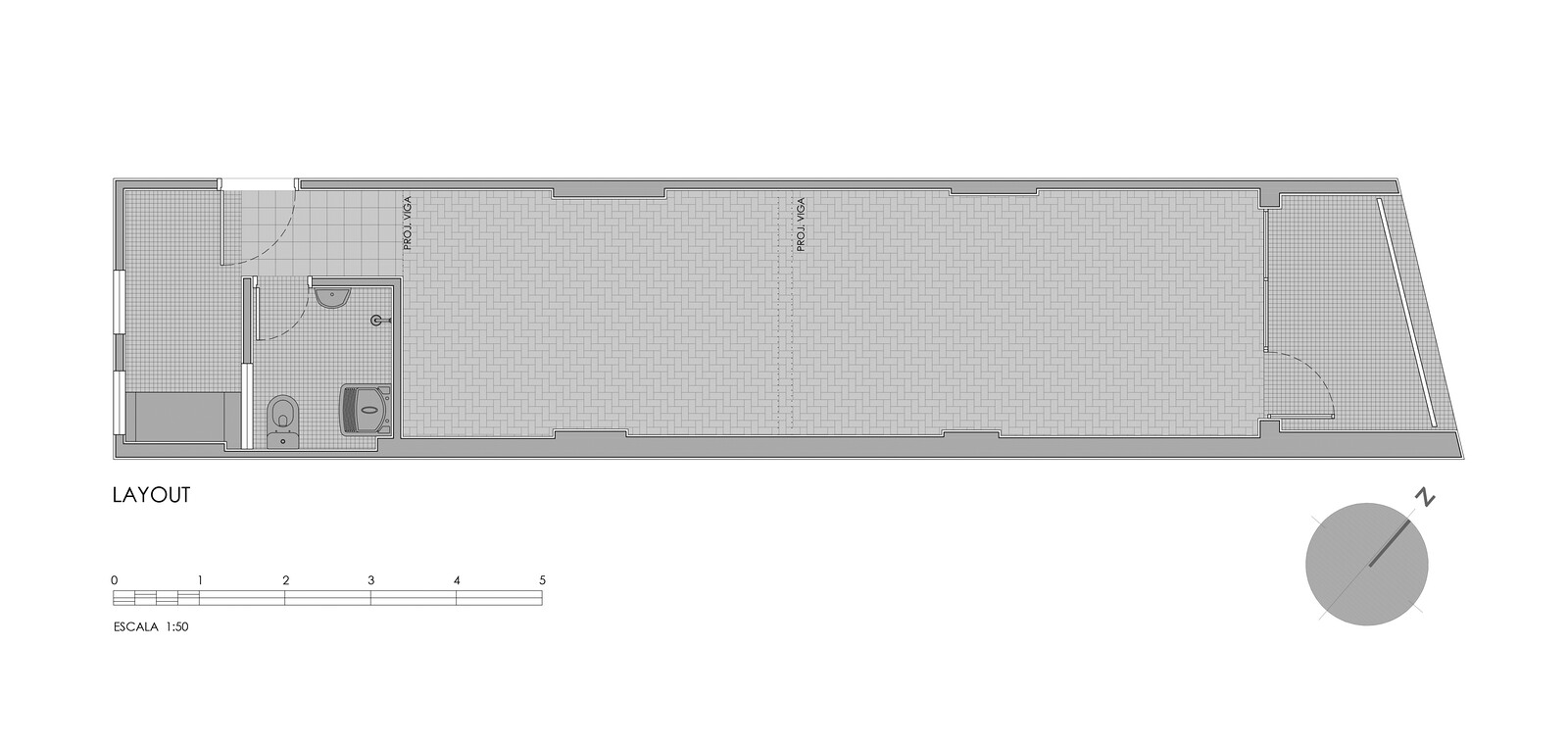

Apartment layout before FICA redesign.

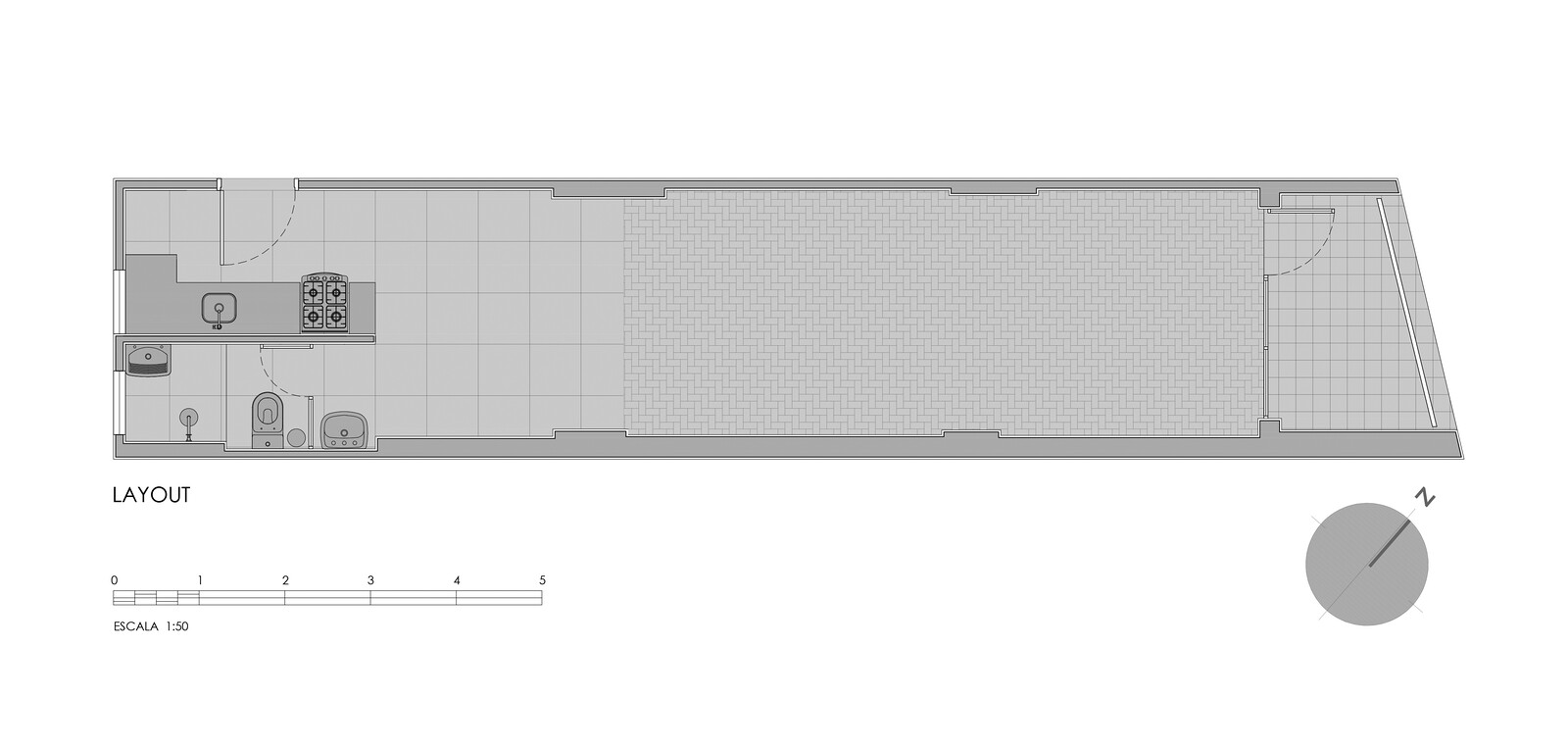

FICA basic apartment layout.

Apartment layout before FICA redesign.

GK You began organizing in 2015 and obtained the first apartment in July 2017. What difference did having a case study apartment make to the project’s fundraising, public profile, and support?

FICA At first, we used the apartment as an exhibition. We were fortunate that the São Paulo Architecture Biennale was happening in October 2017, and they invited us to be part of the exhibition. We officially launched the project during the biennale with a small and simple exhibition of the apartment. This exhibition was really important for us. It’s one thing if you hear about an idea; but if you are inside an apartment that’s made of brick, wood, and glass, and it has a toilet and so on, it’s something else. The apartment was still in bad shape at the time; we still had to raise funding for the renovation. But people could see it was real. Every time someone visited the apartment they were impacted by it. The difference between zero and one is absolute. It’s not just that one is more than zero. One is a qualitatively different animal than zero.

GK How did you choose the family that moved into the first apartment?

FICA There was a long decision process with different criteria. The first thing was income. When we understood how much we would charge in rent, we knew we had to find a family with an income of about two minimum wages, around R$2000. If their income was lower, then our rent would be abusive, and if it was higher, they could find solutions on the market. With this wage and price, a family would not be paying more than 30% of their income in rent. Second, the lessee on the contract needed to be a woman. This is because all the research that we have suggests that a woman ensures the stability of a household. Third, we wanted kids to be around. It’s clearly important for an adult to live in a good place. But for a child, being brought up in a stable home with full access to the city can be transformative. It makes you a different person, gives you different aspirations. Fourth, the person had to work in the downtown area. We either wanted someone who was already living in downtown and was paying too much rent in an overcrowded tenement house, or we wanted someone who was living on the periphery, so that living downtown would mean they didn’t have to commute for three hours. Finally, we had to decide how we would we make the call for applicants. We wanted to make an open call through our website or Facebook page, but we were advised against this due to the fact that we would frustrate many people and they may not understand the criteria. Instead, we were advised to make a shortlist of institutions that we trust and ask them to make a shortlist of people to choose from. We invited nine institutions to give us names.

GK What kind of institutions?

FICA Social movements for housing, a squatted house in the area, an organization giving technical support to homeless people, and an institution that works with teenage pregnancy. Each institution could give us up to three names that would meet our criteria. We hired a psychologist and a social assistant for the selection process, as we didn’t want to make the decision entirely on our own. In the end we had twelve replies, in two rounds of calls. From the twelve we selected the six that matched the criteria, and we did interviews with the six women. Then the psychologist and social assistant made a priority list and told us, “this is the family.”

GK For the first apartment, that detailed level of criteria is super important. It’s essential to find the right family to take the project forward. But do you think in the future you will have a similar process? There’s obviously a danger that you start to exclude more and more people.

FICA We will inevitably exclude people. We plan to go slowly, apartment by apartment. But it’s also not a public policy; we are not the state, so we have no commitment to universality. If the state wants to make it universal, we are ready for that. One activist friend of mine said: “you have to be careful because it looks like you are choosing a standard, well-behaved, welfare state family.” She’s right. It’s a limit of our project. We can’t provide social services or healthcare. We don’t have a doctor. So if something goes wrong with this family, we have no expertise and no staff to deal with these problems. What we can do is improve our model, scale ourselves up in an organic way, and show wider society that affordable housing is sustainable. If one day we have twenty, thirty, 100 apartments, then we can think about addressing social issues.

GK You’re currently searching for the second property to buy. What are the requirements for a FICA apartment?

FICA It needs to be a small apartment, 30–40 square meters, and in a good location near the metro in the downtown area. One thing that proved to be very important to the family we have living in our first apartment was health. Before, the children were sick every second week. Once they are sick, they cannot be in childcare and the tenant could not work. Now that the family has moved into a secure apartment, in a good environment, the children are not sick anymore, and she’s able to work. Another thing that we learned is important is that the family wanted to have a proper living room with a sofa, television, table, and so on. They wanted to host their relatives. They told us in an interview that, on Sundays, their relatives now go to visit them. This is really important to them. They never had a house where they could host people.

GK Why were the ideas of collective funding and cooperative ownership appealing? Were there specific precedents you looked into here?

FICA The first model we were inspired by was the Community Land Trust (CLT) in the UK. We wanted to implement a similar model here, but we realized there would be some difficulties for this in the Brazilian context. In the CLT model, the costs of land and property are separated. The CLT retains ownership of its land, while residents can buy and sell the properties built on top of it. The residents, depending on the CLT, can sell the property at market price—i.e. for a profit—or as a limited equity—i.e. what they bought it for, without profit. In Brazil, with its tradition of informality, if we were to make this kind of split property, this person would charge something on top of it. We have this history of declaring that you sold a property for less than you did, or that you paid fewer taxes on it. It’s very normal for people to do that in Brazil; informal occupation of land is very widespread here.

GK So you were concerned this would lead to another form of property speculation?

FICA We would risk getting into difficult situations. At the same time, we didn’t want our tenant to be the owner. We wanted to build an alternative to private property. If you are poor, research has been showing for years that you can be better off in the city if you rent than if you buy property. We also wanted to build an alternative that was not necessarily public buildings for rent. In São Paulo, we have six or seven buildings that are in a social renting program. Two are for senior people, which work quite well, but the others work very badly: the municipality does not have a policy for defaults and the non-payment rates are very high. It’s not that I don’t believe in the program of social rental. The municipality has some officers who are really engaged in making it work, so it’s not about condemning it. But it is really challenging. We wanted to build an alternative.

GK I’m interested in how your model scales. You’ve got this one apartment that was essentially gifted to you, and you have raised the money for a second. But in a huge city with such a great housing need, this is essentially still just an idea. How does the project grow?

FICA We have a working group trying to find ways to finance impact investment, where people invest money and expect some form of social returns. Our first investment thesis is to buy one of these awful tenement houses, where one family lives in each room, because they are unbelievably good real estate investments. This way we can access the money that poor people are already paying in rent for low-income housing in downtown São Paulo, which is a lot of money. We can then use this money to improve people’s situation and eventually decrease rents. Each family is not paying very much, but for what they get it’s very expensive. Per square meter, these are really high prices. This would be one way of trying to scale up.

GK But if you took over a building, would that not then involve displacing the people already living there to avoid overcrowding? Obviously you would aim to improve the housing conditions of some, but how do you balance it? It seems as though it could create another form of gentrification, or at least displacement.

FICA We would have to take it case by case. We could say: “OK, these three families have to leave, out of twenty, but we will give them some money for the first month in the market.” Or if we have an apartment somewhere else, we can move a family there. We would of course have to check the building. If we would have to displace 80% of the people already living there, we would not buy it. However, this idea is in very preliminary stages, and there are many legal and ethical issues to address before we can move forward with it. We would only do something like this if we felt it was safe and we were sure it would improve people’s lives.

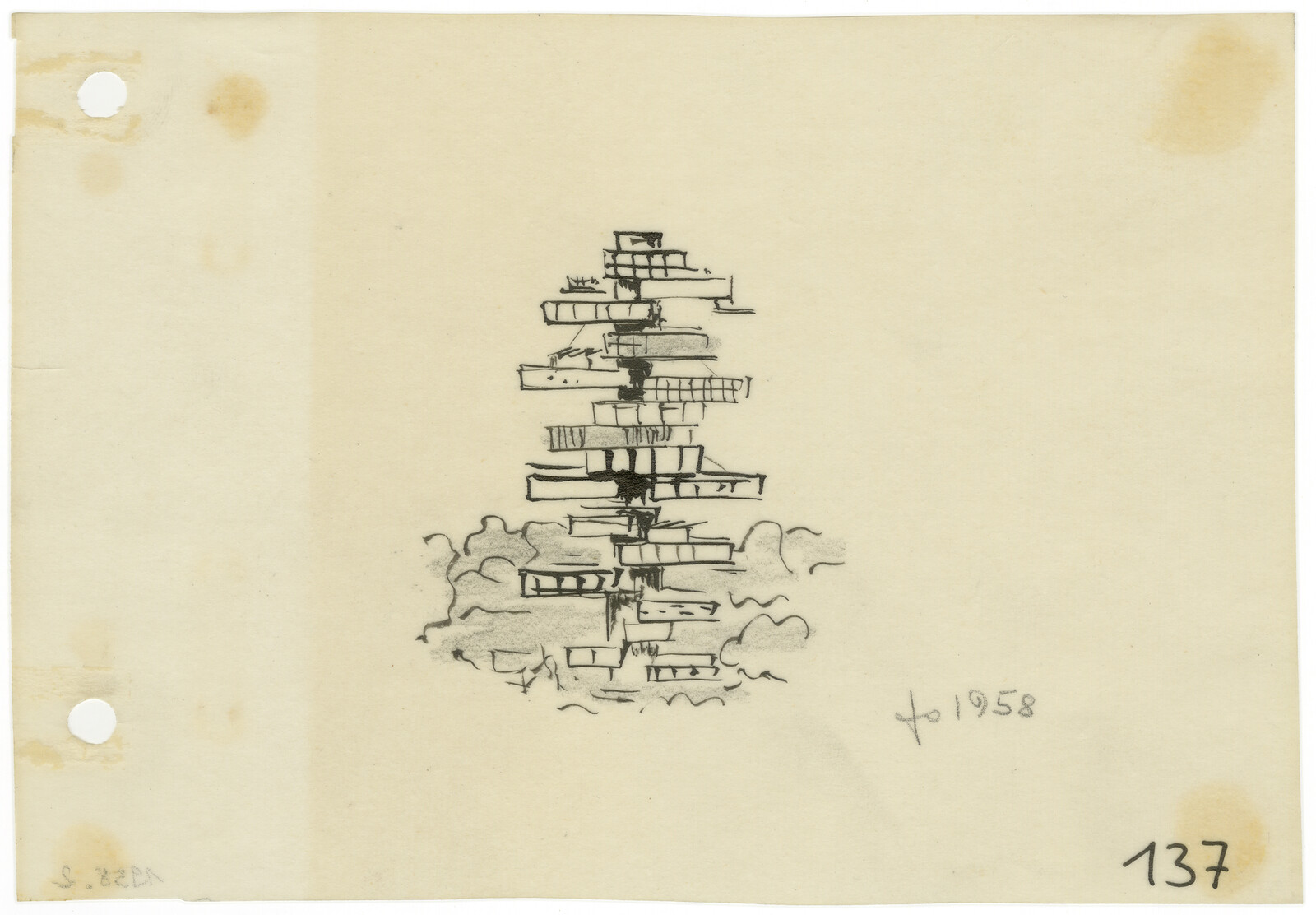

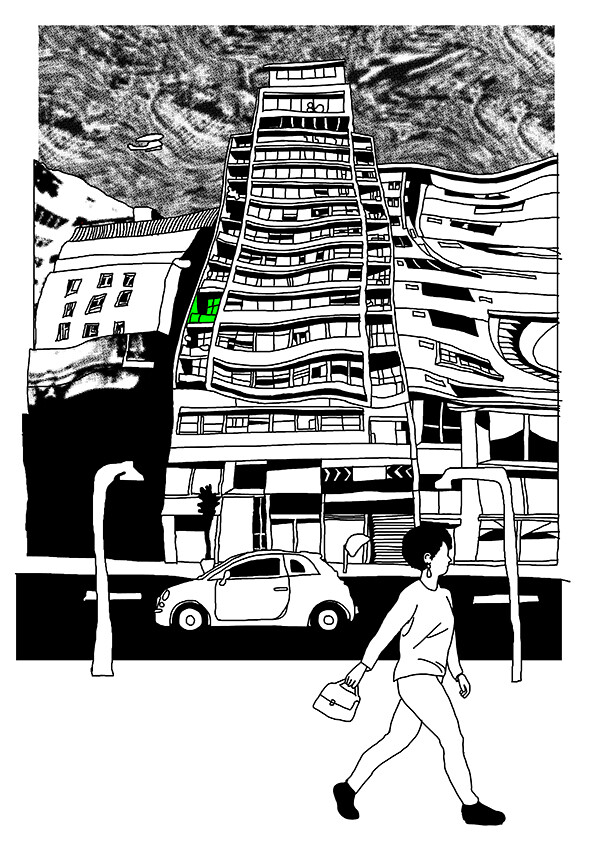

FICA apartment in São Paulo highrise, drawing by Paula Puiupo.

GK Have you had much engagement with the state at this point?

FICA The municipality in São Paulo recognizes our work and they like us, but we don’t have support or subsidies from the state. This would be another way of upscaling, if the public authorities adopt the FICA model as part of public policy. At the moment they are paying R$140million per year in rental vouchers, which simply increases market prices. If we could access the 20,000 buildings where the state is paying rent, we could buy a lot more properties. But it’s not really fair to demand us to upscale ourselves. It’s society’s burden. We have done much more than what was expected of us, which is building the model. The model exists. The burden of scaling up the model is not the responsibility of the people who carved out the model. It’s a societal responsibility.

GK Are there currently other groups currently operating similar models in São Paulo?

FICA This is a major frustration for us. We need other groups like us to appear in case the municipality of São Paulo or other municipalities decide to make a public policy based on non-profit housing. If there’s just one, FICA, it would be very dangerous to make a contract with the state because it would be denounced as a privilege, or something similar. Instead, there needs to be a public call, a bidding process, and we would have to compete with each other for public real estate. We are begging people like us who are well-intentioned, who are interested in housing, who don’t like gentrification, and who are annoyed about evictions and exclusion and segregation, to please build their own associations. We have done so much work to carve out this open source model. We’ve shown how an organization with this model can function. But people are not creating their own groups.

GK Why do you think there is a reluctance on their part?

FICA It is a lot of work, and if people are in the academy they prefer to write their papers. I think people are more comfortable criticizing than proposing, because if you propose you expose yourself. We have exposed ourselves. For example, people have to pay for the housing. It’s not the most progressive housing model that’s possible. R$600 is already too much for the neediest people and we have to justify this. The only way to not be exposed to contradictions like this is to not do it. People are very comfortable not doing anything.

Neil Smith, “Gentrification Generalized: From Local Anomaly to Urban ‘Regeneration’ as Global Urban Strategy,” in Frontiers of Capital: Ethnographic Reflections on the New Economy, eds. Melissa S. Fisher and Greg Downey (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), ➝.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.